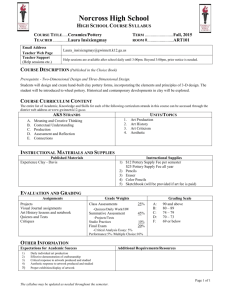

Introduction

advertisement

Nostalgia and Identity: Hand-painted ceramic decoration in Britain, 1870 to 1920 Introduction This thesis discusses hand-painted decoration on British ceramics in the period 1870 to 1920 in the context of changing economic and social climates and gendered employment and occupation. The original impetus for this research came from analysis of ware produced at the South Wales Pottery in Llanelli sometime in the period 1877 to 1920. As the research expanded and links with other potteries were established, it became evident that varied innovations in hand-painted ceramic decoration were influenced by national, local and gendered responses to a period of transition in Britain. In the 1870s social and economic conditions became fractured and considerable changes in demographic structures occurred which affected class and gender relationships over ensuing years. Asa Briggs described the 1870’s as the ‘watershed’ of Queen Victoria’s reign1. It saw the end of the economic boom of the mid Victorian period and the collapse of the agricultural economy. Both industrialists and landowners were facing challenges and looked back to earlier periods of stability and prosperity. The Industrial Revolution had had beneficial and negative impacts on British society and the labouring population. Nineteenth century social commentators such as William Cobbett and John Ruskin had written about the damaging effects on both people and products due to the expansion of industrialisation and urbanisation. Ruskin commented that unlimited development would result in a country “set as thick with chimneys as the masts that stand in the docks of Liverpool; …no meadows, no trees, no gardens.”2 Industrial developments and expansion of empire encouraged national confidence but the disruption and dislocation in employment and lifestyle gave rise to questions about 1 Asa Briggs, A Social History of England (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1983). p. 228 2 John Ruskin, Lecture III, Modern Manufacture and Design, Bradford March 1859. The Two Paths, Collins Clear Type Press, c. 1861. p126 1 individual and national identity and also evoked a culture of nostalgia for the perceived constancy and continuity of earlier agrarian communities. 3 Interest in the state of manufacturing and social conditions began to increase in importance. These wider concerns were reflected in the aesthetics and consumption of domestic interior design and decoration. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was created to display the products and strength of British industry, but it highlighted to many contemporary commentators and design reformers, such as Henry Cole and Owen Jones, the excess in ornamentation and the degree to which quality in design and manufacture in Britain had declined when compared to European continental wares4. William Morris found the exhibits at the Exhibition “wonderfully ugly”.5 Morris, together with members of Morris and Co. as well as the polemicists of the Arts and Crafts Movement, such as Walter Crane and William Lethaby were part of a counter movement that sought to rectify this supposed decline by emphasising the aesthetic and social benefits of craftsman designed and made objects for domestic use. Although the cost of goods from Morris and Co denied the wares to the majority of the population, they influenced popular taste for hand-finished goods. Major public monuments, such as the four lions in Trafalgar Square, sculpted by Sir Edwin Landseer (1867-8) represented national confidence and aspiration of Victorian Britain. In contrast, the every day domestic interior goods, including tablewares and cheaper decorative objects, characterized wider popular taste and culture. The focus of this thesis is on the practice of hand painting on china and the motifs used rather than the recognition of products of particular potteries. Many of the scholarly accounts, which dominate writing on nineteenth century ceramics, focus on identification of shapes and motifs, which are the field of the collector and the John Morley, Liberal politician, writing in 1874 described it as a period of “doubt, hesitation and shivering expectancy” J. Morley On Compromise, 1874, paragraph 28 4 Although Henry Cole and Owen Jones were involved in the Exhibition’s organisation Cole had given evidence to the Select Committee on Arts and Manufacturers in 1836 regarding poor quality of British design. Owen Jones published the Grammar of Ornament in 1856 on the principles of design. 5 J.A. Auerbach, The Great Exhibition 1851, a Nation on Display (Yale University Press, 1999). p 113 3 2 connoisseur.6 Key texts I have used are those that deal with the theories of consumption, identity and nostalgia.7 The wider theories explored in these texts inform detailed analysis in a series of case studies chosen to represent different aspects of the use of hand-painted ceramic practice, which took place in the fiftyyear period. This research has made extensive use of the contemporary style literature, newspapers and popular journals as well as the decennial census records from 1841 to 1911. It also includes information gained through conversations with individuals closely linked through sale or ownership of items. Hand-painted ceramic decoration introduced and developed in the period under research will be shown to have been illustrative of varying facets of nostalgia and identity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By the nineteenth century social, technological and cultural developments as well as trade expansion had introduced variety, sophistication and skill to ceramic manufacture, centred on Stoke-on-Trent but also in other areas to serve local populations. The expansion contributed to the consequent loss of large numbers of individual artisan potters and the decline of hand finishing. Transfer printed ware was largely satisfying the public demand for tablewares that were inexpensive and durable but superior to the coarser country wares. However, an emergent middle class heightened the demand for fashionable distinctive tablewares and aspects beyond the requirements of mere necessity influenced both manufacturers and consumers. Hand-painted earthenware could be decorative, affordable and different from the uniformity of volumeproduced transfer-printed ware that had come to dominate the market. In the South Wales Pottery, Llanelli, hand painting was re-introduced for everyday earthenware in the 1870s and is linked through the decorative designs to potteries in Scotland and South Devon, the motifs having particular local allusions. In Llanelli, 6 P.D.G. Pugh, "Staffordshire Portrait Figures of the Victorian Era," Antique Collector's Club (1987), Robin Reilly, Wedgwood, vol. I & II (London: Macmillan, 1989). 7 John Brewer and Roy Porter, eds., Consumption and the World of Goods (Routledge, 1994), Jonathan Friedman, ed., Consumption and Identity (London: Harwood Academic, 1994), Susan Stewart, On Longing, Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), C Tilley et al., eds., Handbook of Material Culture (London: Sage, 2006). 3 South Wales, a hand-painted cockerel motif achieved a certain iconic status in the late twentieth century for those associated with the town. Research indicated that it could represent localised notions of identity and nostalgia although the items were held to be of little aesthetic merit.8 In the period 1870 to 1920 there were some long-standing and short-lived pottery manufacturers in production. Victoria Bergesen’s Encyclopaedia of British Art Pottery (1991) lists over two hundred and does not include the myriad of potteries throughout the United Kingdom producing everyday ware for local and wider use. Decorative practices included glaze effects, pâte-sur-pâte and hand painting. As well as being used in commercial manufacture, china painting became privately popular as it fulfilled a need for a suitable leisure occupation. The chosen case studies explore contemporary individual decorating as well as small and large-scale commercial production. They demonstrate the variety of ways in which handpainted decoration particularly was a conduit for the culture of nostalgia, acting as a signifier of differing aspects of national, personal and gender identity. Authenticity, of the object’s origins, the motif or the emotional reaction evoked, is a fluid concept and may be consciously or unconsciously construed to create a mythology of the past. In order to contextualize the main body of the research, brief analyses of periods both before 1870 and after 1920, into the twenty-first century, are included in Chapter 2. These demonstrate that a culture of nostalgia and concerns about identity in the late nineteenth century had their origins in the social and economic conditions of the earlier centuries and that the same issues continue to be critical in the twentyfirst century. The case studies commence in Chapter 3 with the Howell and James exhibitions that started in London in 1876. Chapter 4 discusses the involvement of Arts and Crafts Movement members, Alfred and Louise Powell, at Josiah Wedgwood and Co. in the first decades of the twentieth century. Chapter 5 examines the Two early references to the pottery describe it as ‘unpretentious’ and being for every-day use. E. Morton Nance, The Pottery and Porcelain of Swansea and Nantgarw (1942). p 160, n 1 and Dilys Jenkins, Llanelly Pottery (Swansea: Watkins, 1968). p 9 8 4 production of Wemyss Ware and Devon Motto Ware in the 1880s. The final case study, in Chapter 6, deals in detail with the South Wales pottery and the importance of hand painting which started after 1877 and continued until the pottery’s closure in the 1920s. Between 1876 and the early 1890s the ‘Exhibitions of China Painting’ organised by Howell and James impinged on the area of ‘fine art’. Entries came from both men and women of the upper and middle classes and demonstrated the complex distinctions between amateur and professional status. The identifying characteristics of the middle classes came under increasing self-scrutiny in the Victorian period. A woman’s ability and opportunity to work outside the home was constrained by education as well as social and moral attitudes. Dominated by entries from female artists, many of the chosen motifs conformed to gendered expectations but several artists demonstrated their awareness of contemporary aestheticism and fashion. Through these exhibitions, which could provide a covert form of work and income, Victorian motives of philanthropy, propriety and aspiration could be combined. Research into the china painters draws on references in the texts on Victorian female occupation and consumption coupled with the contemporary newspaper reports and decennial census. It reveals details of family backgrounds on known as well as previously undocumented decorators. It shows the wide social spectrum from which they came, and thus expands the understanding of this element of Victorian society. The work of the china painters exhibited at Howell and James is now largely disregarded and few pieces are found in public collections. Whereas the female decorators exhibiting at Howell and James were named and referred to as ‘amateurs’ or ‘artists’, those who worked in industrial environments were largely unknown as individuals and were often referred to as paintresses, thus terminology defined class and gender.9 In the early twentieth century Alfred and Louise Powell trained paintresses for a well-known manufacturer and icon of British ceramic production since the eighteenth century, Josiah Wedgwood and 9 An exception to this was found at Doulton and Co, where some women employed in hand-decoration at the Lambeth factory were referred to themselves as artists in a commemorative volume produced in 1882. Cheryl Buckley, Potters and Paintresses, 1870-1955 (London: The Women's Press, 1990). p 64 5 Sons, with a view to creating more satisfying work and working conditions. The Powells endeavoured to ally the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement with the demands of large-scale commercial pottery production. Alfred and Louise Powell’s lives and work are documented in several texts. Using these texts and the contemporary newspaper and other reports as well as the original pattern books created and used by Wedgwood in the 1900s to 1920s it has been possible to develop new evidence on the nature of the Powells involvement with the work at Wedgwood. The distinct contribution each made is indicative of their personal, individual, lives and backgrounds. The patterns created, including a close reinterpretation of the designs from the eighteenth century, helped to re-establish Wedgwood’s identity as a market leader. The legacy of the Powells’ work and training methods was to allow a few female decorators to emerge as individual artists and established the Powells’ reputation in later literature. Despite the constraints placed on the social and moral lives of the middle class women exhibiting at Howell and James, they signed their work and had more freedom of expression than the ‘paintresses’ trained by the Powells under an Arts and Crafts ethos at Wedgwood. The third case study examines the introduction of hand-painted decoration, which had particular local relevance, at two regional potteries. In the 1880s, the Fife Pottery in Scotland and the Aller Vale Pottery in South Devon each created a distinctive range of hand-painted wares, which were different from the major part of their production. These goods were marketed with the objective of supplying conscious or unconscious demands for items that reflected distinctive nationalist or localised social or cultural characteristics and were a focus for recollection for another and different lifestyle. The authenticity of the Scottish identification or the Devon seaside souvenir was a matter of presentation and inference rather than reality. The Wemyss ware products of the Fife Pottery and the Motto Ware of Aller Vale Art Pottery and South Devon, whilst distinct in character and market, provided opportunity for theoretical, comparative discussion on the significance of the 6 origins of decorative motifs, in their manufacture and consumption, and the importance of actual or perceived authenticity to narrative interpretations. The case study of the South Wales Pottery in Llanelly covers the period 1877 to 1920. In 1877 two cousins introduced a range of new and fresh hand-painted wares including a cockerel motif. This motif, the identities of two decorators and local associations have considerable impact on the later value of the wares and their function as signifiers of emotional connections with the town into the modern day. Primary sources, such as newspapers, minute books and local archives are used to establish the pottery’s early twentieth century identity in the town and provide a basis for discussion on how apparently ephemeral objects can have important social significance. The pottery’s links with the potteries in Stoke-on-Trent and the Welsh Industries Association are especially illustrative of the issues of a Welsh versus English identity for both the pottery and its purchasers that continue into the modern day. Consideration of hand-painted ceramic decoration in a variety of contexts in a period of social dislocation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century has provided a basis for a discussion of the motivations behind production and consumption of ephemeral objects and shows that these items were and are foci of nostalgia and inform the interpretation of national and individual identity. Detailed research into individual makers and decorators reveals new information on their social conditions and lives. Analysis beyond the broader theories related to production and consumption and the interpretation of objects of particular potteries, individual decorators and the motifs, shows that hand-painted decoration was significant to the way in which class, gender or local associations were both conveyed and presented. Grand objects can convey the identity and nostalgic emotions of a nation, but it is the minor ephemeral decoration that has personal and local importance. 7 Auerbach, J.A. The Great Exhibition 1851, a Nation on Display: Yale University Press, 1999. Brewer, John, and Roy Porter, eds. Consumption and the World of Goods: Routledge, 1994. Briggs, Asa. A Social History of England. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1983. Buckley, Cheryl. Potters and Paintresses, 1870-1955. London: The Women's Press, 1990. Friedman, Jonathan, ed. Consumption and Identity. London: Harwood Academic, 1994. Jenkins, Dilys. Llanelly Pottery. Swansea: Watkins, 1968. Nance, E. Morton. The Pottery and Porcelain of Swansea and Nantgarw, 1942. Pugh, P.D.G. "Staffordshire Portrait Figures of the Victorian Era." Antique Collector's Club (1987). Reilly, Robin. Wedgwood. Vol. I & II. London: Macmillan, 1989. Stewart, Susan. On Longing, Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993. Tilley, C, W Keane, S Kuchler, M Rowlands, and P Spyer, eds. Handbook of Material Culture. London: Sage, 2006. 8