Sergio Guerra - AnthroCompsPrep

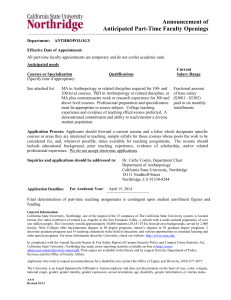

advertisement

Sergio Guerra ANTH 600: Rethinking the Four-Field Approach To Split or Not to Split: An Anthropological Approach to the Rift between Archaeology and Anthropology “Boas insisted that the appearance of bounded disciplinarity was deceptive: the origins of anthropology were ‘multifarious,’ and there were already ‘indications of its breaking up (Stocking, Jr. 1995).” So went “The History of Anthropology” according to Boas. Franz Boas essentially defined the boundaries of anthropology at the beginning of the 20th century. He characterized the “sacred bundle” or the four-field approach used throughout the United States today, consisting of linguistics, biological and socio-cultural anthropology and archaeology (Boas 1904). These four sub-fields were intended to aid each other, allowing for a more holistic and cross-cultural interpretation of the study of humankind. Yet, as predicted by one of the forefathers of anthropology, a rift would eventually make its way to surface and the field would be fragmented for years to come. In the present, anthropology is fighting to keep its “sacred bundle” intact, and if it wishes to keep its very existence as well, anthropology must do all that it can to see that archaeology stays put. In Europe, separate archaeology departments are commonplace (Wiseman 2002). There, archaeology has been separate from anthropology for decades. However, when it comes to the United States, some express shock that it still remains under the umbrella of anthropology (Hodder 2005). If one looks at the development of archaeology and anthropology however, it is clear that they had different origins in Europe and the U.S. In Europe, the growth of archaeology is tied historically and politically with the project of the nation-state. The political vision and ambitions of the emerging nation-states provided the primary concern for major museum and state antiquity authorities to define the antiquity and historical depth of the national tradition in the 19th century (Hodder 2005). In the U.S. however, the initial influence on the development of archaeological institutions was more closely related to colonialism in North America, tied to defining the pre-colonial Native American “other,” thus immediately connecting archaeology to anthropology. But where did the rift occur between archaeology and anthropology in the United States? Some believe that this turn for the worse happened with the move away from culture-history by socio-cultural anthropology and eventually archaeology in the 1960s (Gillespie et al. 2003). Ultimately, anthropology went on to take a more narrow view of history, in opposition to the generalizing and nomothetic “science” employed by archaeology (Gillespie et al. 2003). Yet others contend that there are serious method and theory issues between archaeology and anthropology, as they no longer share perspectives that frame common research goals (Gillespie et al. 2003). The main focus of this essay however, deals with the division within anthropology in the academic setting. Hodder highlights several issues that archaeologists have identified as their main points of contention. As an academic field, archaeology feels that it is being held back, developmentally stunted by a lack of ability to shape curricula to their interests and to those of their students, mainly due to the domination of socio-cultural anthropology in the discipline (Hodder 2005). Many critics contend that the socio-cultural approach dictates the direction of the field, regardless of the research aims of the other sub-fields. In this way, it guides funding, hoards budgets, and shapes the curriculum away from developing necessary archaeological techniques and methods. As a result, the development of archaeological science in the United States has been impeded. One of the effects of this stunted development is the confusion which exists between archaeological science and scientific archaeology in the U.S. This confusion has inhibited proper funding of archaeological science and contributed to the lack of appropriate training of archaeologists in U.S. anthropology departments (Hodder 2005). As contract archaeology has developed, problems with the professionalization of archaeology, which focuses less on anthropological questions and more on technical skills, has caused many to believe that they are not able to properly train their students, instead having to focus on learning about the broader field and anthropological principles which they feel are not the most essential components of a contract archaeologist’s training (Hodder 2005). Many archaeologists also feel that there position as a branch of anthropology has restrained their ability to develop debates with other related disciplines and seek connections outside of the sacred bundle (Hodder 2005). At the University of Pennsylvania, the four-field approach has for the most part, been able to avoid major turmoil. However, conflicts have arisen as professors grapple for courses and to shift the research questions away from the socio-cultural focus. Based on first-hand accounts, it is clear that professors recognize the power which socio-cultural anthropology has in the department. They admit it does direct funding, enrollment, and the overall direction of research, but this often comes down to a very specific reason, rankings. Departments are ranked based on the strength of their socio-cultural programs. This causes the socio-cultural sub-field to receive more of the focus, more of the funding and as a result, more of the students. However, recent efforts by Dr. Preucel and others have managed to emphasize the importance of each sub-field to contributing to the overall strength of the anthropology department and the research being conducted. The benefits of collaboration and cross-field understanding are recognized and accentuated. Even though efforts are being made to bring the department together, a complete and total “harmony” at all times, obviously cannot be achieved. Everyone’s goals and wishes cannot be appeased at once, but efforts can be made to reduce future friction and preserve the cordial relations being built in the present. So what can be done to prevent any future divisions? As of right now, and into the foreseeable future, socio-cultural anthropology will continue directing the general focus of the field, but this by no means should inhibit the other sub-fields from pursuing other anthropologically relevant endeavors. This will require more flexibility on the part of the department to allow a wider range of classes and to foster a greater understanding of the methods being used across the discipline. If anthropology is to remain a whole, understanding is key. With the recent turn in research, the sub-fields of anthropology are more than ever able to contribute to each other. Each sub-field can focus on their specific area, but incorporate key and applicable methods from their sister sub-fields to produce a more holistic and well-rounded study. Archaeologists can benefit tremendously from socio-cultural approaches towards interaction with communities. Socio-cultural anthropology can benefit from reciprocal archaeology’s work to understand traditional cultural places and cultural affiliations via combining integrative anthropology and scientific archaeology (Gillespie et al. 2003) and so forth. Regardless of the amount of effort required, all that can be done, must be done to keep archaeology within anthropology. Archaeology is a crucial aspect of the anthropological spirit and in many ways embodies all that anthropology is founded on. As Susan Gillespie, Rosemary Joyce, and Deborah Nichols express, archaeology focuses “on integrating past and present, sciences and humanities, social processes and their material correlates, nature and culture-the big questions of who we are, where we came from, how we got here, and where we are going (Gillespie et al. 2003).” Without archaeology, anthropology may lose more than a sub-field, it may lose its very nature. Works Cited Boas, Franz 1904. The history of anthropology. Science 20 (512): 513-524. Gillespie, Susan D., Rosemary A. Joyce, Deborah L. Nichols 2003. Archaeology is anthropology. In Archaeology is Anthropology, Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, No. 13 edited by S.D. Gillespie and D. Nichols, Arlington: American Anthropological Association, pp. 155-169. Hodder, Ian 2005. An archaeology of the four-field approach in anthropology in the United States. In Unwrapping the Sacred Bundle: Reflections on the Disciplining of Anthropology, ed. D.A. Segal and S.J. Yanagisako, Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 126-159. Stocking, Jr., George W. 1995: Delimiting anthropology: Historical reflections on the boundaries of a boundless discipline. Social Research 62 (4): 933-966. Wiseman, James 2002: Archaeology as an academic discipline. The SAA Archaeological Record 2(3): 8-10.