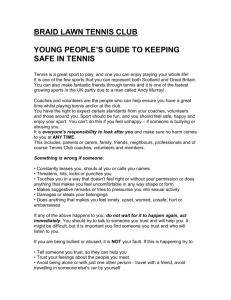

LONG TERM PLAYER DEVELOPMENT

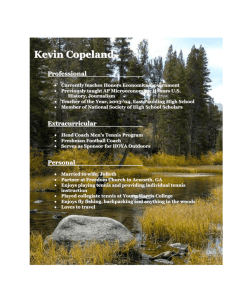

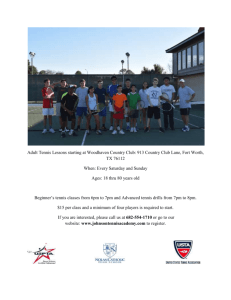

advertisement