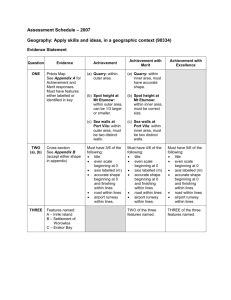

TMBV - Unesco

advertisement