Click here

advertisement

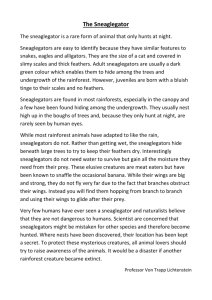

The Sacred Messengers By Julie Collier Photo by Jim Parks Julie Collier and Jim Parks are Massachusetts-licensed raptor rehabilitators who form a partnership they call Wingmasters. Their organization is dedicated to increasing public awareness and appreciation for birds of prey. Julie and Jim lecture fulltime in schools, museums and libraries with nonreleasable raptors. Jim blends his love of photography with his love of birds of prey by producing portraits of the resident raptors he and Julie care for. His photo below shows Lakota, a 25-yearold golden eagle. Julie is a writer as well as an artist whose goal is to capture the individuality of each bird of prey in her pen-and-ink drawings. Her Native American ancestry is Creek and Chickasaw. Their web site is www.wingmasters.net. The Native American warrior stares straight ahead, his unblinking eye set off by the forked eyestripe of a peregrine falcon. His long hair is pulled into a neat coil behind his head. An eagle’s wing feather curves upward from the hairknot, framing the man’s head. This warrior, shaped of cold-hammered copper, is approximately 700 years old. Unearthed in Oklahoma, the copper fragment is a tantalizing reminder of the longvanished Mississippian cultures. The Mississippian people, named for their homeland in the fertile floodplains of the Mississippi Valley, were farmers whose success at raising crops allowed them to develop complex, highly stratified societies headed by powerful chiefs. Flourishing from approximately AD 1000 to 1500 in the eastern half of the United States as far north as Wisconsin, these were skilled craftspeople whose art demonstrates their reverence for birds of prey. Copper plaques like the warrior excavated in Oklahoma are a characteristic artifact of Mississippian cultures. The metal sheets may have been worn as priestly headdresses. Many depict a composite being, a raptor-man with the body of a bird of prey and a face that combines human and raptorial characteristics. In fact, the raptor-man is a central image in Mississippian art. An engraved seashell made into a cup gives him the immense wing and tail feathers of an eagle. Another seashell, carved into a pendant, portrays him with massive eagle feet. These Mississippian artifacts are not the earliest evidence we have for an ancient, pervasive reverence for raptors among the Native people of North America. The Hopewell culture flourished in southern Ohio from roughly 200 BC to AD 400. These hunter-gatherers buried their dead in large earthworks and many were interred with a wealth of offerings. One man was laid out with a small cloth-wrapped hawk or falcon on his chest. Nearby were two mica cut-outs of eagle feet. Another burial contained a sheet-copper peregrine falcon, unmistakably depicted from its hoodlike head markings and notched beak to the spear-shaped markings on its chest. These raptor images, spanning many centuries, may symbolize spiritual beings that prehistoric Native Americans thought of as holding dominion over the cosmos. The bird of prey depictions can also be interpreted as spiritual messengers, intermediaries between the all-powerful gods and benighted humans, fated to act out the gods’ bidding without understanding. Many modern-day Native Americans are animists, followers of an ancient belief system that recognizes spiritual forces manifest in the natural world. Spirit messengers that appear in dreams and visions help people move correctly along their life path. Birds of prey are often seen as visual symbols or metaphors of these sacred messengers, and to this day raptor images and feathers are worn or carried by Native Americans to connect them with spirit powers. Raptor feathers have been used on Native American regalia such as headdresses, shields and fans for centuries, probably for millennia. Tail and wing feathers from golden and bald eagles were the most prized and the most frequently used. Northeastern Woodland tribes singled out two other favorite raptors, whose feathers were often worn on headdresses. One was a bird they called the black hawk, which may have been the peregrine falcon. The other was the red-tailed hawk, which followed the Northeastern Woodland people into the New England area, hunting over the new clearings the farmers carved out of the primeval forest. One type of Northeastern Woodland headdress that was worn by both men and women was a headband of animal skin, often decorated with shell beads or dyed porcupine quills (glass beads were used after the arrival of Europeans). Feathers attached to the bands varied in type and arrangement depending upon the tribal affiliation, status and spiritual vision of the wearer. Only men among the Northeastern Woodland tribes wore the gustoweh, a cap covered with small overlapping feathers. While these were often from non-raptors such as the wild turkey or ruffed grouse, pride of place on the gustoweh was reserved for a single eagle tail feather at the cap’s top, set loosely to pivot with the movements of the wearer. The roach was another male Woodland headdress style, far more widespread in its use than the purely Northeastern gustoweh. A crest of dyed animal hair, often from a white-tailed deer or porcupine, was fanned out with a bone spreader and pinned to the wearer’s hair. One eagle tail feather was fitted into a socket on the spreader. Woodland headdresses feature eagle feathers because these massive raptors were viewed as powerful entities, helpers to humanity from the spirit realm. But why just one eagle feather when Western tribes wore ornate warbonnets that might feature dozens? The Lakota Sioux, for example, developed the best-known of all Native American headdresses, a cap encircled with eagle tail feathers whose placement symbolized the sun. This style is sometimes called a swept-back warbonnet because the feathers angle gracefully backward. Trailers with additional feathers were sometimes added. The Western tribes were horsemen who regarded warfare as an opportunity for personal glory. Their headdresses were designed to enhance a mounted warrior’s appearance. The attached eagle feathers recorded war exploits. It is no coincidence that the swept-back warbonnet of the Lakota was created in the 1700’s, when they first acquired horses from the Europeans. Woodland people, by contrast, rarely used horses and did not use eagle feathers to record war exploits for a very good reason – their preferred kind was in short supply. The favorite eagle feather of most Native Americans was the tail feather of a first-year golden eagle, white with a wide black tip. The trouble was that the golden eagle was a largely Western species, rarely encountered in the Northeast. Bald eagles were far more abundant in the East, and the speckled black-and-cream tail feathers of first-year balds were esteemed. But they were never as soughtafter as golden eagle tail feathers were and still are. Today Native Americans can possess golden and bald eagle feathers to protect their spiritual connection with these great aerial hunters. See the article on Feather Law in this issue. Raptor feathers of all kinds on Native regalia speak of an ancient bond between these people and the birds that link them to the spirit realm. Golden eagle, "Lakota." Photo by Jim Parks of Wingmasters