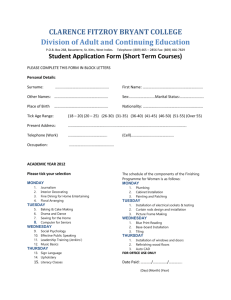

Ceramic and Assimilated Fine Art Mechanisms

advertisement

Ceramic and Assimilated Fine Art Mechanisms Ceramic and Installation The exact nature of Installation Art is devoid of a general consensus with a wide variance of views. For an intelligent and thorough background view the writings of Keith Broadfoot. 1 More specifically term “Ceramic Installation” has emerged as commonplace vocabulary within the applied art arena. Artists, educators and writers as well as gallery owners engage and display the phrase to determine and categorise work that references the term “Installation”2. Contemporary ceramic artists for the most part approach installation from the route and perspectives of the Applied Arts, where foundations have been laid to the existence of the ceramic object and its placement within traditional constructs. In the context of ceramic installation in the Twenty First Century the ceramicist ultimately displays commitment and association to the material clay, working within a constructed language that functions within an applied art ceramic discourse. This commitment to clay has obvious connections to the artist’s academic grounding where material, process and history of the discipline act as a platform for exploration within this arena. 1 Keith Broadfoot The End of the Line: Installation Art Today, What Is Installation? Editors Adam Geczy and Benjamin Genocchio, Power Publications Sydney 2001, p.69. 2 Nicolas De Oliveira, Nicola Oxley and Michael Petry On Installation The term ‘installation’ has established itself firmly as part of the vocabulary of the visual arts. Many artists and critics have refered to the activity as an expression of the concept of Gesammtkunstwerk, a total work of art, as it appears to borrow from a vast spectrum of disciplines. Its history, while often ill-defined, grows out of the individual narratives presented by architecture, painting, sculpture, theatre and performance. Art & Design Vol 8 5/6 May-June 1993, p.7. The arena of installation within ceramics has, and still does, portray works that are predominantly in the medium of clay. Developments however within applied art ceramic installation have seen the emergence of the juxtaposition of clay with other materials including video and new digital technologies. Installation works engage clay in numerous formats utilising the material in both un-fired and post-fired representations. The use of clay and in particular its use by the ceramic artist has encouraged and developed installation within the constructs of the applied art discipline. To what extent however has this development been influenced by the assimilation of fine art language and mechanisms, and as a consequence, has a unique ceramic area been constructed that differs from the constructs of generic installation3 patterns. In establishing a definition of ceramic installation the terminology needs clarification as to what it constitutes both visually and theoretically. Installation Art The emergence of our current understanding and reference to installation art has its origins in the middle of the Twentieth Century, particularly since the 1950’s according to many commentators. Writers such as Ronald J Onorato link fundamental aspects such as habitation of a physical site, connection to real conditions and the bridging of traditional fine art boundaries4. The formulation and execution of works typically includes both the use of constructed elements and the use of readymade, found and recycled objects. Ceramic, due to its physical nature and ubiquity, manifests itself as a material that alludes 3 For definition of installation see Kristine Stiles I/Eye/Oculus: performance, installation and video, Themes in Contemporary Art Edited by Gill Perry and Paul Wood, p.186. 4 Blurring the Boundaries: Installation Art 1969-1996 Ronald J. Onorato, p.13. to the properties of the constructs of installation, where its role can play out several functions. Due to an extensive familiarisation with the material clay and the numerous applications it occupies within society and culture, the use of ceramic, especially within the field of installation, has not been as an exclusive medium of the trained ceramic artist but has been utilised without the necessity for formalised specialist training. The fluidity of the natural material and its capability to be transformed into numerous applications displays ceramic as a material that constitutes multiple functions within the structure, function and fabric of society, hence the utilisation of the ceramic ready-made within the field of installation art. The use of the ready-made ceramic object invites informed interpretation, as clay transformed from a non-characteristic form in its original state, assumes the form of another, thus adopting new interpretation as a consequence. The layering of meaning or multiple reading becomes extended as additional contexts are laid upon the ceramic ready-made object when it forms part of the constructs of the installation framework. This context for multiple reading provides significance for the analysis of ceramic when it is used within the arena of installation art. The use of ceramic within the historical context of fine art installation is displayed both as a ready-made, where objects have already been formed from the material clay, and as a constructive material where the artist works with clay beginning from its noncharacteristic format. An iconic artwork within the early development of installation art utilising ceramic is Equivalent VIII by Carl Andre5. The work consists of one hundred and twenty firebricks arranged on the floor in two layers of sixty to form a rectangle. The artwork has not only become iconic in the context of the development of installation art but also in the provocation of front-page media coverage, which entails the introduction of contemporary art into the wider cultural domain, albeit within a negative context6. Within the work the material ceramic constitutes the ready-made object, in this case the brick, which is used in multiples to construct the installation work. Andre’s professed aim with regard to materials was to ‘impose’ properties on materials but to ‘reveal’ those properties7 In revealing the properties of the materials and specifically clay what are we able to assess and construct from analysing the installation. Martin Ries work on Carl Andre and Equivalent VIII offers extensive critique upon the artist and his work. 8 The use of brick, a transformation and creation of another, derived from the substance clay, are referenced as humble materials, basic to building, construction and manufacture. 5 Martin Ries, Carl Andre (1935 - ) Equivalent VIII, Carl Andre was one of the founders of the art movement known as Minimalism, Systemic, or ABC Art. It is an art that seeks to eliminate everything decorative, extraneous and additive, reducing all components to art’s purest elements; it is precise, cerebral and austere rather than accessible. www.martinries.com/article1991CA.htm. 6 “Normally the cultural divide between the popular press and avant-garde art circle is so wide that neither pays attention to the other. However, in 1976 a significant exception to this rule occurred. A recession in the British economy alerted the Daily Mirror to the news-value of stories exposing wasteful public expenditure. (The purchase of Andre’s ‘bricks’ by the Tate Gallery some years before was first reported in the Business Section of the Sunday Times on 15 February 1976). By condemning the Andre sculpture the paper was able to pander to the presumed philistinism of its readers in respect of Modern Art, while simultaneously gaining kudos as the watchdog of the public purse. The British art establishment, used to a condition of autonomy and superiority, was disturbed to find itself subjected to public ridicule from such an unexpected quarter.”John A. Walker 1976: Bricks and Brickbats, Art and Outrage: Provocation, Controversy And The Visual Arts, p.76. 7 Ibid. 8 Martin Ries Carl Andre (1935 - ) Equivalent VIII. www.martinries.com/article1991CA.htm. Andre makes reference to the bricks and other materials in his works as particles9 where multiples of the object or material are used to construct artworks. The multiplication of the ceramic object has a certain resonance for the applied art ceramist within the construction of ceramic installation works, where this formula resides centrally within contemporary ceramic practice. Repetition: Installation and the multiple ceramic object The notion of ceramic installation, one that is associated to the constructs of applied art discourse, has generated momentum within contemporary ceramic practice and has become embedded within the language and terminology of both the practitioner and theorist. What distinctions or similarities though lie between ceramic installation, and installation associated within the fine art arena? The distinction needs to be investigated within the context of the use of ceramic familiarity and how this is managed within an applied art discourse. In reference to distinctions, Glen R. Brown constructs a number of critical statements about the aims of the Postmodern artist who gets involved as a maker of installations as against the work and aims of the contemporary craftsperson. 10 Brown comments on the approach by the applied artist differing somewhat from the fine artist and references the application of an attachment to tradition within an applied art 9 My particles are all more or less standards of the economy because I believe in using the materials or the society in the form the society does not use them; whereas works like Pop Art use the forms of society but make them from different materials. Carl Andre excerpt taken from symposium; Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Lawrence Weiner, Windham College, Putney, Vt., April 30-May31by Dan graham – Six Years: The dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972 Lucy Lippard. 10 Glen R. Brown Memory Serves: Time, Space and the Ceramic Installation – Critical Ceramics 2001. construct. Operating within this framework the ceramist therefore has obvious connections to both traditions and an obvious attachment to the material clay. The construction and development of ceramic installation places this attachment centrally where work is constructed within the applied art taxonomy. The creation of ceramic installation within the field of ceramics displays the presentation of the ceramic object and most generally its multiplication and repetition. This format and the occupation with the multiple form asks the question as to whether the multiplication of the object constitutes and confirms the administration of the term installation, and to what extent the term is reliant on the power of repetition. The application of repetition and particularly the use of the multiple object by ceramic artists has developed as a visual ceramic device that associates with the language that constitutes the developed terminology of ceramic installation. It is terminology that is used frequently and also administered quite widely within applied art discourse. The associations made between both the term and the visual connection often display routes of observation where the applied artist draws on meaning within tradition and object function. The use of multiplication within contemporary ceramic installation is widely evident and can be referenced in the United Kingdom through the work of Claire Twomey. This artists’ work has been exhibited widely to both applied art and fine art audiences, operating within varying structures and spaces. The development of Twomey’s work introduces several issues that offer considerable content for the much needed debate and critique around this theme within contemporary ceramic. Twomey’s work operates within the public space and makes central reference to the developed ideology of the white cube11 and the association and connection that installation has with the gallery concept and site-specific setting. The work Shoal consists of multiple cast porcelain toy submarines, which are suspended with fishing line in an arrangement that references the movement of fish through water. The work operates on a number of levels placing the element of repetition at its centre. The power of repetition, particularly within the context of ceramic installation, demonstrates strength within this work. The scale of the work and its impact upon the space relies heavily on the area occupied by the multiplication of the object and thus the impact of the space12 that surrounds the work. When analysing more closely the ceramists’ occupation with the multiple object and the association to large areas of space, a direct observation can be made with process and technical elements, where the artist is often directed by constraints of the material properties of clay and the scale of the kiln, which can place limits on the size of fired ceramic pieces. 11 Brian O’Doherty Inside the White Cube The Ideology of the Gallery Space O’Doherty describes the modern gallery space as “constructed along laws as rigorous as those for building a medieval church.” The basic principal behind these laws, he notes, is that “The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. Walls are painted white. The ceiling becomes the source of light….The art is free, as the saying used to go, ‘to take on its own life’, p.7. 12 Jean Baudrillard The System of Objects An objet d’art may seem more precious when it is surrounded by empty space. ‘Atmosphere’ is thus very often created merely by a formal arrangement which ‘personalizes’ particular objects through the disposition of empty space. In the case of serially produced objects, conversely, a shortage of space destroys atmosphere by depriving objects of the luxury of ‘breathing’, p.61. Limitative constructs have a bearing on the capabilities of ceramic and it is possible that this is central to approach, forming an integral part of the construction of installation works within ceramic practice. This demonstrates that limitations also encourage alternative solutions and enquiry, something that is evident within the work Shoal where repetition on a primary level addresses the notion of scale. The element of repetition and in particular the format used within the work Shoal constitutes multiple readings. On a primary level, as mentioned above, there is an attachment to the physical constraints of the capabilities of clay and the technicalities of process. Referencing the work further, the repeated porcelain object has been made by the construction of a plaster mould that produces a representation13 of the original toy, which in turn is also a representation of the considerably larger original. The use of mimesis is central within Twomey’s work where the process of the production of multiples, imitates the original ready-made through a direct substitution of the material clay. The process used is a technique called slip-casting14 which is used universally within the ceramic industry to produce multiple objects, which are fundamentally functional or decorative. This imitation or replication of an object in the material clay makes direct reference to the mass production of domestic objects and occupies a core 13 Brian Dillon On the philosophy of Repetition- Repetition undoes representation with the twin weapons of theft and the gift: it’s only by stealing, or giving unconditionally, that we enter into the realm of true repetition, where the same and the different overlap without asking anything of each other. Frieze magazine number 77 September 2003, pp.76-79. 14 “A clay body which will cast well must be designed with the physical nature of casting slips taken into account. The process of casting requires a fluid suspension of clay in water, which will flow readily but which will not settle in the moulds. The clay slip must pour smoothly from the mould, leaving a surface which is free from lumps or roughness. Furthermore, pieces which are cast must not wet the mould unduly, must release themselves from the mould upon drying, and must not have an excessive shrinkage or warpage.” See Casting Clays, pp.39-43. Daniel Rhodes Clays and Glazes for the Potter Pitman House Limited 1973. area within Twomey’s subsequent works. Heirloom consists of multiple cast ceramic domestic objects that have been halved and subsequently placed around the walls of the white gallery space. The cast pieces are too white, and seem to emerge directly from the wall. For a critique of this piece see the original catalogue for the Mission House Gallery Exhibition 2004 written by Nicolas Rena. 15 The projection of mimesis within Heirloom leads Rena to observe that the objects are no longer real things and have become a poor cousin of the original. Whilst this can have a certain remit with regards to removing historical trace elements and functionality, the original forms are on the whole mass-produced and made from relatively cheap materials. The choice of Twomey to cast the pieces in porcelain commits them to an elevated status when evaluated within ceramic practice, where the material resides at the higher end of the clay hierarchy. The familiarity of the objects and the connection to the material make obvious links to the field of ceramic where associations and connections can be made. The familiarities placed with the familiar objects are altered through the distortion of the object and its unconventional placement within the white space16. The unconventional arrangement disrupts the notion of the function of the ceramic objects, which constitute the work Heirloom, where physical placement and function become altered in a new reading 15 Nicholas Rena 2004 Exhibition catalogue Heirloom Clare Twomey A Mission Gallery exhibition with support from the Arts Council of Wales – Heirloom is a project supported by The Surrey Institute of Art & Design. 16 Brian O’Doherty Inside the White Cube The Ideology of the Gallery Space Conversely, things become art in a space where powerful ideas about art focus on them. Indeed, the object frequently becomes the medium through which these ideas are manifested and proffered for discussion – a popular form of late modernist academicism (“ideas are more interesting than art”). p.14. framed within the gallery setting. Space within the modern gallery redefines conventional associations to the object and plays a central role within Twomey’s work. In observing Brian O’Doherty’s analysis of the white cube where he states that art becomes free as a consequence of the ‘laws of construction’ of the modern gallery, then Heirloom and other ceramic works possess the ability to be exhibited free from previous connections. This possibly, has more resonance where the gallery space is not connected to an applied art discourse, where terminology has the capability to introduce predetermined possibilities for observation and evaluation. The nomenclature of the gallery retains the capabilities to inform constructed space17 and instruct the spectator accordingly. In his analysis of the gallery space O’Doherty questions the idea of threats and hierarchies and conceptualises the view that ‘space now is not just where things happen; things make space happen’. 18 This observation with regards to the gallery space fits the constructs of the fine art space but can the same be applied to the applied art gallery where increasingly installation work constitutes a considerable part of the exhibition program? The work Heirloom was exhibited and conceived for the Mission Gallery sited in Swansea, Wales. The gallery has a diverse exhibition program and thus constructs a relationship with the spectator and as a consequence the spectator with the space. The audience, therefore, is encouraged to apply interpretations to the work within the context of the gallery and the developments of art discourse and culture that inform the reading of space as a consequence of installation development. Developments within elements of contemporary fine art installation have 17 Brian O’Doherty Inside the White Cube The Ideology of the Gallery Space Modernist space redefines the observer’s status, tinkers with his self-image. Modernism’s conception of space, not its subject matter, may be what the public rightly conceives as threatening. 18 Ibid introduced considerable change in the way space is read within the gallery space. This has much to do with the advancement of digital technologies and its capabilities to alter surroundings.19 This progression of the reading of space and, as a consequence, the works, contribute to the development of the audience in relation to the reading of works. Within the white cube space the interaction between installation artworks and the spectator has multiplied over the last fifty years where installation now forms a considerable part of artistic outputs, and gallery exhibition programs. The spectator has become familiarised with the use of space over of the period of time and has developed an understanding of the constructs of the white cube and its relationship to installation art20. Is it possible to construct a similar analysis within applied art structures where ceramic installation works have not received the same amount of gallery exposure and thereby have, an underdeveloped element of critical debate and evaluation. The difference or similarity has strong connections to the history and familiarity with display within the applied art gallery space. In historically reading the applied art space with particular reference to work in clay the audience has become familiarised with numerous applications and the utilisation of the gallery. 19 Installation Art in the New Millennium Nicolas de Oliveira, Nicola Oxley and Michael Petry Escape The artwork’s aim to elicit sensual pleasure through sensory manipulation is significant as it mirrors developments in contemporary life: the theorist Frederic Jameson states that ‘We are submerged…to the point where our postmodern bodies are bereft of spatial coordinates and practically incapable of distantiation.’ p.49. 20 Ibid., Exchange and Interaction As Installation has moved into the centre of artistic practice and with it, embraced its constant mobility, it has reached new types of audiences, resulting in different modes of audience participation, p.107. The singular object placed on the plinth surely delivers itself as the most ubiquitous method of display and this has several formats where groupings or series of objects occupy similar display elements. The gallery floor and walls have also become commonplace territory within the ceramist’s visual language and form of expression. This has connections to the development of sculptural ceramics, which in turn is influenced by the language and structures of sculpture. The elements of display within contemporary ceramics display reference to the dynamics of sculpture and the gallery space and as a result the ceramic audience has become familiarised with the concept of work displayed off the plinth. In considering the symbiosis between the ceramic spectator and the gallery space, Mark Rosenthal comments on the reading of the space from sculpture to installation. He is of the view that sculpture is a singular object, whereas an installation can consist of many, or in fact none, declaring that installation to an extent multiplies and magnifies the medium of sculpture.21 Rosenthal references a reaction to the views of Rosalind Krauss, and remarks that the development of installation is far greater than the suggestion of Krauss that sculpture had merely seized a broader area within fine art discourse22. Rosenthal’s text discusses the change in the expectations of the spectator where the individual art object and the plinth have become absent, and a newer art that favours the multiple object, image or experience, has become commonplace within both the gallery and the conscience of the 21 Mark Rosenthal Understanding Installation Art From Duchamp to Holzer Prestel 2003, p.25. Rosalind Krauss Sculpture in the Expanded Field, in The Anti-Aesthetic: Post Modern Culture, ed. Hal Foster, London and Sydney: Pluto Press, 1983, pp.31-42. 22 spectator. The absence of the plinth and the projection of the multiple object, also resides within contemporary ceramics, both within installation works and sculptural ceramics. In observing that a similar evolution has occurred and similarities can be made with the transgression of the installation from sculpture, the applied arts display somewhat similar constructs to ceramic installation, which impact upon the applied art gallery and the audience of the space. The development of ceramic installation displays similarities with that of the absence of the singular object and display away from the plinth in sculpture. These developments within ceramic installation occurred somewhat after the developments within fine art. Edmund de Waal has commented extensively on this issue and his views carry a great deal of conviction when constructing a contemporary historical narrative in the field of ceramics where post rationalisation is afforded the luxury of constructing a history within the structures of Postmodernism23. The construction and analysis of the development of ceramic within this arena and its association to past relationships with art movements displays a number of elements that are visible within contemporary ceramics and specifically installation ceramic works. These visible elements are contained within the constructs of Postmodernism where its structure and hegemony allow for considerable exploration. The developments of ceramics within this period display numerous facets, which include both sculptural and installation works. Garth Clark comments on the development of Postmodernism and ceramics as being a ‘marriage made in artworld heaven’. 24 23 Charles Jencks What is Post-Modernism? Academy Editions/St. Martin’s Press 1986, p.56. “It’s the realisation that we can return to a previous era and technology, at the price of finding it slightly different. The Post-Modern situation allows its sensibility to be a compound of previous ones, a palimpsest, just as the information world itself depends on technologies and energies quite different from its own.” 24 Garth Clark Meaning and memory: The Roots of Postmodern Ceramics 1960-1980 Postmodern Ceramics Mark Del Vecchio Thames and Hudson 2001, p.8. Garth Clark’s observations, centre around the liberation that has been afforded ceramics by the Postmodern era and makes reference to the mining of every semiotic meaning inherent in clay. This, as Clark asserts, includes borrowing and reinterpreting from ceramics vast history, whilst also analysing the practical elements of the medium including process and technique. It is these elements that are most commonly displayed within ceramic installations, and in turn question the legitimacy of repetition when considered in comparison to the constructs of fine art installation. Some of the fundamental elements that reside within the term installation can be applied to both fine art and applied art, as indicated by De Olivera, Oxley and Petry, in their book where they offer their view on installation and conclude that, ‘installation art is its parts in relation to each other but is experienced as a whole’. 25 It is possible when considering such an assertion to state that the mechanisms and structures of fine art installation attain the ability to transcend into applied art discourse. The dissemination of installation structures and particularly the elements of process and multiplicity as mentioned in the text are parts that are central to contemporary ceramic installation, where previous and emerging work is constructed and displayed referencing these elements. Several artists associated with applied art ceramics make direct reference to the elements considered essential to installation art as cited in the previous quotation. Multiplicity of 25 Nicolas De Olivera, Nicola Oxley and Micheal Petry On Installation, Installation Art, Art & Design Vol 9 5/6 May-June 1993, p.11. the ceramic form or object is referenced and displayed widely both within the gallery space and site-specific locations. Observations of ceramic installation point to considered routes of investigation where works display reference to abstracted forms, mimetic objects and direct utilisation of the vessel. Multiplicity and the Vessel Multiplication or repetition, a fundamental element of installation art has been embedded within ceramic practice since early man began to form clay, particularly with the continued use of the wheel. The process of repeated forms can be referenced to both the ceramic industry and the studio ceramist. The studio ceramist tends to work within a serial context where multiple forms are created as a consequence of mastering process and this has particular relevance to the act of throwing on the potters’ wheel. The repeated form of the studio ceramist has also much to do with cost effectiveness and production value. Major consideration is also the cost effective use of the kiln where it is common practice to commence firing only when the kiln is full. Multiple forms and in particular vessels produced on the wheel are usually produced for wider consumption where an individual will create a range of work for his or her market. The process of slip casting also fits into this category where plaster moulds are formed so that numerous identical forms can be produced. This method is associated with industrial process methods but is widely used by individual practitioners, where the technique can be achieved without the need for industrial machinery. There is also evidence of collaborative works as a result of the artists linking with industry. Ceramists that work with the multiple vessel, include Piet Stockmans,26 whose installation Urnen, features numerous repeated vessels placed within the site-specific space of a Gothic abbey in Heino, the Netherlands. Stockman’s simple forms use only two elements the white of the clay body and the application of blue slip. The installation work at the abbey consists of thousands of replicated vessels, which are in turn displayed in repetition, metonymically referencing the absent congregation. This formulae within his work, transcends the notion of scale where systematic repetition of the vessel is also evident in the piece Object 5 with 153 Vessels. Whilst this work is considerably smaller in scale it contains the same elements of display, which centre around the placement of objects. The placing and repetition of the vessel is also contained within the work of Edmund de Waal, IBID 2004, which consists of 29 porcelain vessels of varying size. The work is displayed upon a table setting where the vessels are arranged within the permitted space. De Waal remarks upon the pleasure of experimentation of repetition, an element that occupies a central space within ceramic practice. By endorsing this commonplace ceramic element de Waal is administering confirmation of installation status upon the work. Publication of the work by the British Council in Denmark actually references the work as such. If we compare images of the exhibited work in the different locations the work is displayed both times within the gallery setting. One image depicts the work sited upon a contemporary wooden table within an environment reminiscent of a domestic interior. The other image depicts the work on pristine white enclosed 26 Piet Stockmans B. Leopoldsburg, Belgium, 1940. See Biographies Postmodern Ceramics Mark Del Vecchio Thames and Hudson 2001, p.216. structures within the white cube space. The two very different settings have the ability to project quite different readings of the work, and although both venues are galleries the environments within are considerably different. If we return to Ronald Onorato’s suggestion from earlier in the text, that fundamental aspects of installation include the artworks habitation of a physical site, then both displays of the work conform to one of the fundamental remits of installation. The site and venue of exhibition may change considerably but the collective objects, in the case of de Waal, repeated vessels, maintain their physical properties. The alignment and juxtaposition of the twenty-nine vessels may also alter when the work is re-exhibited, but the complete work still constitutes the individual ceramic elements. This realignment and collective display is perhaps most visible within the work of Gwyn Hanssen Pigott.27 The work Still Life 2, 1995 consists of seven vessels displayed collectively within a grouping as a single piece of work. The arrangement of her work was derived from the realisation that the display of the individual vessels was being ignored in galleries and in reaction to this Pigott began to group the elements to form works that contain multiple vessels. The grouping of the repeated forms as a consequence gained recognition, projecting and adherence to the constructs of ceramic installation. This format of display and in particular the use of the multiple vessel has encouraged certain readings within ceramic discourse. 27 Gwen Hanssen Pigott B. Ballarat, Australia, 1935. See Biographies, Postmodern Ceramics Mark Del Vecchio Thames & Hudson 2003, p.211. The grouping or repetition of the vessel has potential to remove the administration of objectification of the singular form in favour of the admission of confirmation as installation, a pattern that is repeated within contemporary ceramics. This grouping and repetition of objects however, is not only confined to ceramics but ‘has become ubiquitous in contemporary art’. Oliveira, Oxley and Petra go even further and declare that ‘repetition has become an essential condition of production and reception’. 28 Identical comparisons can be constructed between applied art ceramics and fine art when analysing this succinct part of installation. Whilst comparisons can be made, differences also occur which connect to the reading of process within ceramic practice. Glen R. Brown observes distinct differences between the ceramic artist and fine artist where he states that the ceramic artist approaches installation from an informed accumulated perspective contained within applied art discourse. 29 With this in mind when reading the ceramic installation and mapping developments, process, the reading of objects and their place within tradition become highly visible. These elements within ceramics have bearing upon the notion of repetition, which occurs as a consequence of fundamental process. That these are central components points to the questioning as to how the developments within ceramic installation have been as a result of the influence and consequence of the osmosis of fine art discourse. If what already existed within its structures can attain validation as installation when presented within a different context, 28 Nicolas De Oliveira, Nicola Oxley, Michael Petry, Installation Art in the New Millennium Thames & Hudson 2003, p.168. 29 Glen R. Brown Memory Serves: Time, Space and the Ceramic Installation Critical Ceramics article NCECA Conference 2001. then the hegemony of fine art installation has proved pivotal to ceramic developments, especially within this context. One observation that can be constructed from the ceramists discussed and also the majority of all ceramists making installation is that works consist on the whole of constructed elements that have been produced by the artist. This is to say that the use of the ready-made, and, in particular, the ready-made ceramic object is almost absent from the ceramist’s palette. If we compare this to the use of the ready-made object within the constructs of fine art installation then we can observe a considerable disparity in approach to the elements contained within the work. The unifying characteristics of the artists contained within the text and ceramic artists generally, is their connection to the material clay. Material affinity Connections between ceramic installation and the ceramic artists projection of the selfmanipulated material are synonymous with visual observations made within this area. The artists discussed thus far, exhibit multiple repeated vessels that are a manifestation of direct occupation with clay and the practice of ceramics. It is an element that seems grounded within the artistic outputs contained by the terminology ceramic installation. The work Field by Antony Gormley, is constructed around many of the elements that have been discussed so far. The use of multiplication and repetition and the rejection of the ready-made in favour of hand manipulated clay, indeed all can be offered as comparison to the ceramists approach to installation. The one considerable difference is that Gormley is a sculptor and not a ceramic artist. This also offers explanation as to why the piece Field, although discussed frequently within ceramic discourse, avoids the administration of the terminology ‘ceramic installation.’ As the critical discussion develops around this area within ceramics notably the descriptors of work have begun to confirm work as solely installation, demonstrating the removal of ‘ceramic’. As artists begin to display work outside of the craft/applied art gallery, particularly as a result of a growing acceptance of ceramic in fine art spaces, then perhaps clarity of terminology is in the process of becoming a defunct possibility. Ceramic repetition and spectatorship Repetition of ceramic objects and multiplication through the space seem to confirm familiarity with installation, however the context and arrangement work to displace it. Deleuze30 makes reference to the notion of repetition in Hume’s31 thesis in that, ‘Repetition changes nothing in the object repeated, but does change something in the mind which contemplates it’.32 In addressing the constructs of installation with emphasis on the presentation of such works within ceramic discourse, the position of the spectator becomes central to the 30 Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995) was professor of philosophy at the University of Paris, Vincennes-St. Denis. In 1968 Deleuze published his doctoral thesis Difference and Repetition. 31 David Hume (1711-1776), Scottish philosopher, historian and essayist. 32 Gilles Deleuze Difference & Repetition, Repetition for Itself, Translated by Paul Patton The Athlone Press 2001, p.70. mechanisms and formats of installation art. The associations made between the work and the viewer, introduce multiple readings, which occur as a consequence of spectatorship. When applying the notion of the reading of serial objects within ceramic installation Deleuze seminal work remarks on the psychology of human interpretation in respect of any consideration of repetition of an object’. 33 Pointing to an association between the object and the subject where analysis of these elements introduces the notion of difference. In constructing comparisons with the use of repetition within ceramic installation what are we able to construct from the association between the element of difference and the spectator. When Deleuze states that repetition changes nothing in the object repeated but changes something in the mind which contemplates it, it is this change that offers expanded investigation within the area of ceramic installation. The interaction between the repeated ceramic object and spectator can be best illustrated and analysed through the work consciousness/conscience by Clare Twomey. The installation work consists of approximately seven thousand cast identical bone china forms. The multiple constructions are laid in repetition on the floor within the space totally occupying the pedestrian area. To step into the space requires the spectator to actively become part of the installation work and, in doing so, the viewer destroys the multiple objects beneath their feet. Mark Currah offers an excellent review of the piece 33 Ibid., p.71. on Twomey’s own website and he is surely right to view the central importance of focussing attention on, ‘the moment of the artworks reception’. 34 Twomey’s work offers perhaps the most extreme example of the interaction with spectatorship where the viewer undertakes physical actions to activate the work, hence becoming participant in the event, whilst simultaneously administering confirmation upon the artwork. The action of consecutively destroying the forms is a repeated act and this serves to magnify the element of repetition. This element is manifested through the multiplication of forms and the repetition of those forms within the layout of the space. The complex overlaying of repetitive associations within Twomey’s work can be appropriately defined in Deleuze’s analysis where he states that difference inhabits repetition, and is actively represented through the intermediary of passive synthesis.35 Seeking to uncover difference or the unfamiliar within repetitive formats has perhaps become less problematic as the category of installation ceramics becomes more malleable. Developments within the field and expansion of the area display connection to familiarity and the exploration of difference. As a reference connections can be made with Krauss’s text Sculpture in the Expanded Field, where she argues with conviction the case of expansion within sculpture, especially in the context of post war American art. 36 As the ceramic spectator becomes familiar with developments within the field through new works, alternative spaces and display, the spectator therefore possesses the ability to 34 Mark Currah critical review of consciousness/conscience 2003 www.claretwomey.com Gilles Deleuze Difference & Repetition, see chapter Repetition for Itself, p.77. 36 Rosalind E. Krauss The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths see chapter Sculpture in the Expanded Field, pp.277-290. The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts 1985. 35 reference and make associations to the fundamental aspects of the discipline. Krauss discusses sculpture, by asserting that the new is made comfortable by being made familiar. This certainly has a resonance for ceramic installation and subsequent implications for spectatorship. The history of ceramic is abundant with reference to repetition and seriality, notably where it forms a fundamental element within numerous aspects of process and practice. Repeated form and imagery have occupied a central space within the area of studio pottery, industrial production and more recently with the contemporary ceramic artist. A connection can be confirmed with Krauss’s statement where new works have the capacity to become comfortable as a consequence of familiarity. This, as highlighted through Twomey’s work, has perhaps developed as a consequence of progression within the field of ceramics and the evolving display of installation work.37 The spectator of contemporary ceramic has become familiar with clay and installation, indeed probably supported by the fine artists use of the medium within this context. Global exposure to the work Field by Gormley, and the use of clay within the gallery space by Andy Goldsworthy, in his work Clay Wall 2000, can be cited as examples to demonstrate how familiar the spectator has become with the use of clay within the wider context of installation art. These two artists, although not connected with ceramic practice, have presented clay within the white cube space, and, as a consequence heightened the connection to familiarity and spectatorship. The ceramic spectator is felt to be well informed of the possibilities for the use of clay within the context of 37 ‘Clay has to value itself in the deliberation of how to communicate’. Clare Twomey, excerpt from a fifty- two minute interview with the artist 03/03/05 London. Twomey discusses the area of ceramic installation expanding upon practice and experience within this area. installation, enhanced by fine artist utilisation and developments within ceramic practice. This points to a familiarity but what position does the spectator occupy within the context of an applied art discourse. The spectator is in some way central to the definitions of installation art. Claire Bishop has gone some way to create a model in her recent critical history of installation art. In this she focuses in on the viewer as what she calls a ‘literal presence’ in that installation art differs significantly from the viewers location aligned to more traditional media. 38 If we reference this model against the constructs of installation within applied art discourse it is possible to offer definition within regards to the relationship between spectator and work. Bishop comments further within her text on complications with regards to commenting on installation works. She clearly puts the view that discussion on any piece of installation art is most effective if the piece has been experienced first hand. In her words, ‘you had to be there’, this point in particular certainly has a strong resonance. 39 This has central significance and can best be discussed through the work by Twomey consciousness/conscience where actual active spectatorship is acknowledged and the experience commented upon. The work as illustrated and discussed in the text is a temporal piece, which has existed in a number of art spaces globally. As the work has a limited existence and is not on permanent display, references to the piece are made 38 39 Claire Bishop Installation Art A critical History Tate Publishing 2005, p.6. Ibid., p.10. through documental photographic and video evidence or just memory. As the spectator is physically central to the activation of the work, these readings of the piece offer substantially different interpretations. The definition of spectator merges into participant within this work as experienced as an active spectator at the exhibition A Secret History of Clay, Tate Liverpool, 2004. The work compromised a significantly smaller installation than previously exhibited, where the components had completely covered the gallery floor. Here the components occupied the space between the entrance from one gallery to the next. The expanse was too wide to step over to continue viewing other works, the only option, to walk on the brittle clay forms thus activating the work whilst undertaking the motion. As the title suggests there is a moment of consciousness prior to breakage when the viewer contemplates a number of elements that are placed in front of them. These elements become relevant when the spectator is faced with the actual event, thus the viewer becomes part of the installation. Similar emotion simply cannot be experienced by photographic or video documentation as the moment of consciousness is removed, as is the act of destruction and the post element of conscience. A number of issues became apparent as a spectator at Tate Liverpool. The primary issue is the notion of being the first to enter into the space and thus the first to become part of the work. The work was untouched pristine in its layout. As a ceramic practitioner initial experience addressed the notion of the conscious element of the vulnerability of the material but more notably an awkward sense of self consciousness about the destruction of the work in the gallery setting whilst surrounded by other spectators40. 40 Ibid., see paragraph Activation and decentring, p.11-12. Bishop comments: There is one more argument that this book presents: that the history of installation art’s relationship to the viewer is underpinned by two ideas. The first of these is the idea of ‘activating’ the viewing subject, and the second is that of ‘decentring’. Because viewers are addressed directly by every work of installation art – by sheer virtue of The invitation to commit vandalism within the piece subjects the viewer to a heightened awareness of themselves and each other and an almost self-alienation within the space. This can be referenced to Bishop’s argument where she states that two fundamental ideas within installation art are that of activation and decentring. Certainly with Twomey’s piece the spectator both activates the artwork and also becomes decentred simultaneously. If the spectator were not to break the components, and by doing so physically activating the work, an element of activation would still reside in the work, where the spectator would consciously makes the decision not to destroy the pieces, but contemplates the event and makes a considered judgement. This element of connection between installation and spectatorship brings into question the nature of confirming status upon works from the ceramic arena when analysed within the constructs discussed. The argument revolves around the terminology of installation and questions the appropriate use of the term within applied art ceramic discipline. By appropriate use that is to say a confirmation of clarity around the terminology within ceramic constructs. The word installation is used widely within ceramic discourse encompassing a broad expanse of practical output. However, this points to both the encompassing of and the unification of work when contained by the terminology. The distinction according to Bishop between the installation of art and installation art is certainly relevant to ceramic language. It is Bishop that paradoxically gives a clear line of the fact that these pieces are large enough for us to enter them – our experience is markedly different from that of traditional painting and sculpture. Instead of representing texture, space, light and so on, installation art presents these elements directly for us to experience. This introduces an emphasis on sensory immediacy, on physical participation (the viewer must walk into and around the work), and on a heightened awareness of other visitors who become part of the piece. sight on the blurring of these distinctions with the progression of time within the fine art arena, the argument can be extended to note that there exists the case for closer scrutiny of the terms within a ceramic discourse. 41 Ceramic: Installation art versus Installation of art The terminology ‘ceramic installation’ introduces the argument as to whether a said work of art constitutes the confirmation as installation art or installation of art. This argument has particular significance within contemporary ceramics as descriptors and utilisation of the term encompass a broad disparity of practice. As discussed above a central function to the didacticism of installation is the role of spectatorship42. The difference between looking and spectating are particularly significant in the evaluation of a ceramic artwork as fitting either of the constructs. The work of Twomey as previously highlighted connects with the notion of spectating, where the viewer becomes actively involved within the work. Her works are as stated earlier clearly defined and demonstrate a connection with developed discourse around installation art. The analysis becomes more difficult when the area becomes blurred, indicating confusion as to the application of looking or spectating. The blurring of boundaries contained within installation ceramic practice have been encouraged as a consequence of the diversity that the terminology ‘installation’ introduces into the canon. Installation art according to my interpretation of Bishop again focuses on the physical entry into a work as being the appropriate way to 41 Ibid., see section What is installation art?, p.6-8. The term ’looking’ is superceded in installation by the concept of ‘spectating’ which assumes a higher involvement by the audience. See chapter On Installation Nicolas De Oliveira, Nicola Oxley, Michael Petry, p.7. Installation Art, Art & Design Vol 8 5/6 May-June 1993. 42 experience it, as a consequence the categorisation of installation works is directly relative to the experience of the viewer. 43 This indication certainly has relevance to ceramic within applied art discourse and offers critical insight into the categorisation of installation contained within the constructs of the discipline of ceramics. In the text Bishop points towards the artists structuring of the work, which in turn possesses the ability for categorisation as a consequence of viewer experience. This is certainly a fundamental observation that needs to be analysed collectively with other criteria to uncover the differentiation in ceramic discourse between installation art and installation of art. To question a difference, the notion of familiarity, and in particular the ceramic familiar becomes significant within this evaluation. The central element within ceramic installation is clay and predominantly this is based around the format of the object. The presentation of the material occurs in numerous formats including physical and non-physical representations, by non-physical the indication is towards photographic and video elements. The ceramic object, in its many formats, becomes highly significant within the constructs of installation, particularly, as indicated here within a ceramic discourse. The significance placed upon objects, is discussed in an authoritative written piece by Ilya Kabakov where he discusses global difference in artistic principles and comments on formulations of installation, especially 43 Claire Bishop Installation Art A Critical History Tate Publishing 2005 See chapter The viewer, pp.8-11. the relative differences between the so called west (Western Europe and North America) and the rest of the world. 44 The focus on the object according to Kabakov and others no doubt, displays similarities with ceramic installation, which in turn, is supported through the positioning of a familiarity with clay. In observing familiarity and analysing its application within ceramic installation a number of issues materialise. Consideration has to be made towards the referencing of familiarity in works that contain non-ceramic elements. This has particular significance when ceramic is juxtaposed with another material, or when ceramic operates through another medium. The argument, in this case, revolves around the issue of the power of the non-ceramic medium and its relevance in assigning status to a work when it steps outside the realm of familiarity. In constructing an argument within ceramics for the difference between installation art and installation of art, observations can be placed with objects or elements contained within the work. As discussed earlier in the text a considerable number of ceramic installations contain repeated identical forms whether hand formed or direct replications of ready-made objects. Although the ready-made ceramic object is largely absent from applied art ceramic installation the interplay between cast and the original creates an extended field of exploration.45 The repeated objects are commonly dispersed through allocated space occupying both traditional formats for display and more frequently 44 Ilya Kabakov In the Installations, The text as the Basis of Visual Expression edited by Zdenek Felix, Cologne: Oktagon 2000, pp 359-61. Ideas of the Postmodern, The Condition of History, Art in Theory 1900-2000, edited by Charles Harrison & Paul Wood Blackwell publishing 2003, p.1175. 45 Dawn Ades, Neil Cox, David Hopkins, Marcel Duchamp, Thames and Hudson 1999 See Chapter 8: Replicas, Casts and the Infra-thin, pp.172-189. unconventional formats, which with continued development, assimilate within the administration of familiarity. The works by Magaretha Daepp, and Marek Cecula, consist of repeated identical forms, which support the juxtaposition of both ceramic and other media. The two works make reference to the element of display and utilise other elements accordingly. Daepp’s piece, Archaeology of the Future 1993, explores the notion of museum display portraying repeated ceramic forms within an archival context. The considered disparity between the contemporary shelving and replicated industrial forms, in contrast to the use of unglazed terracotta heightens the awareness of the position held by ceramic within the pantheon of artistic media. As the work suggests, the familiarity with historical ceramic museum display is offered for contemporary digestion and re-evaluation. Cecula’s pieces, Hygiene Series-Untitled IV, 1995 and Hygiene Series-Untitled V, 1996, also contain the notion of display and utilise non-ceramic elements within the installation. The works consist of replicated ceramic forms, which resemble hospital sanitary ware, they are displayed upon equally clinical constructed tables. For a detailed critique of the piece see Gabi de Wald’s exhibition catalogue entry, a central theme of which is the lack of intimacy in the piece and the implications of such. 46 The direct replication of mass-produced objects is contained within both of the artists presented work and can be acknowledged with several other ceramic artists operating within ceramic installation. Some work solely with clay, whilst others employ additional 46 Gabi deWald, excerpt from ‘Hygiene’ exhibition catalogue, Postmodern Ceramics, Mark Del Vecchio, Thames and Hudson 2001, p.189. materials. We can perhaps conclude that these works fit the constructs of installation art within the remit of ceramic discourse. Both works identify with familiar forms that are manifested as a consequence of direct mimetic replication. Replication of forms also exists within the work of Søren Ubisch. Construction, 1998, the piece consists of multiple ceramic elements that are pieced together to construct a transparent wall, the complete work occupies the space between the gallery floor and ceiling. The scale of the work requires the viewer to walk around the piece and experience the scale of the fragile construction within the context of the architectural setting. The work by Ubisch and particularly the piece Breaking up of Ice, 1992 by Pekka Tapio Paikkari both consist solely of the material clay which is presented in the absence of any familiar object based connection. The works present an association with ceramic installation art where the projection of process and the materiality of clay become the determining factors. The indication of the works presented above, are that they demonstrate the hegemony of installation art residing within a ceramic remit. The boundaries of installation art and installation of art become more difficult when the installed work consists of multiple objects, which do not employ the elements of replication or operate through mimetic structures. The return to the notion of looking and spectating also becomes heightened in this situation. Where the object is formed as a one off piece and displayed collectively, the reading of such works become more difficult, consequentially the grouping of such objects can be administered with the definitions of installation of art. This difficulty with identifying work within the blurred boundaries seems to be commonplace within ceramics. The word installation is used so frequently as a descriptor, that the authentic foundation of the term has become blurred as a consequence of assimilation. This in turn has introduced work into the ceramic canon that operates within the authentic context of installation, but also within constructs that exaggerate the terminology to produce an expanded field. Within the expanded use of the terminology, perhaps as a consequence of continuous employment, the definition has developed to encompass an array of work that operates across the blurred boundaries. In support of this notion reference can be made to the opening statement of the chapter where Broadfoot acknowledges that each example of installation art requires its own descriptors. This administration also introduces the acknowledgement of difference within expanded areas. As the definitions within ceramic discourse expand and the application of assimilated terminology becomes part of commonplace language and practice, the adoption and development of installation is naturally aligned to descriptors within the field of ceramics. This however, as indicated, introduces the argument as to whether a work constitutes the administration of installation art or installation of art. The confident use of the term ceramic installation as descriptor within contemporary applied art has perhaps contributed to the blurred definition within ceramic discourse. This can also be aligned to installation art generally, where considerable development and expansion has occurred since the term began to be used in the middle of the Twentieth Century. Julie H. Reiss correctly highlights the gradual insertion of the term installation in standard art publications over the last twenty years with the effect that that, installation had become a specific genre by the late 1980’s. 47 A central point indicated within Reiss’s selected definitions of installation is the relationship and acknowledgement of the gallery space. It is this pivotal element of installation art, which also contributes to the debate around installation art and installation of art within a ceramic dialogue. In the context of the beginnings of installation art spectators were encouraged to physically participate in the work. An artist who initially encouraged the notion of audience involvement is Allan Kaprow. His work of the late 1950s was shown in independent galleries in New York, including the work Penny Arcade 1956 where the audience had to physically move canvas strips so that the works hung on the wall could be viewed.48 This introduction to physical participation can be closely associated with Twomey’s work consciouness/conscience, where the viewer actively engages with material and object within the gallery space. The physical engagement of the object or exhibited piece is however alien to gallery policy and perhaps even more so within the field of ceramics given the fragile nature of the material. The policy of non-physical engagement with artworks within galleries has been 47 Julie H.Reiss From Margin to Center The Spaces of Installation Art, The MIT Press 1999, see chapter Introduction, pp.11-24. 48 Ibid., p.10-11. See chapter Environments. challenged by numerous artists including Carl Andre. Reiss discusses Andre’s work 144 Lead Square 1969 demonstrating the juxtaposition between audience and gallery. 49 Although the audience physically interacted with the work in 1969 the scenario for equivalent participation with Andre’s work in the Twenty First Century is removed. This is perhaps as a consequence of both the status of the artist and the pricing of the work within the contemporary art market. It is also notable that whilst the work can be viewed as installation, it also crosses the boundary into sculpture, which historically within the gallery setting adheres to the policy of non-physical interaction. This observation can be applied to ceramics in the sense that on the most part ceramics are not physically interacted with within the gallery environment. There are exceptions to the rule as in the work by Twomey where the artist invites the audience to physically participate. On the most part ceramic installation relies on visual interaction, which in turn may stimulate other senses. With this in mind differentiation between installation art and installation of art becomes difficult particularly when the audience has become familiar with developments in ceramic that have moved away from the traditional plinth, to include alternative methods of display. The complication with extended terminology is that it becomes difficult to categorise work as the boundaries have expanded. The blurring of boundaries is most significant when one off ceramic pieces are displayed collectively and administered with the title installation. It becomes almost impossible not to objectify each piece individually and collectively submit materiality as confirmation of installation. The works by Sueharu Fukami Installation at Togakuda Gallery, Kyoto, Japan, 1995 fit with 49 Ibid., p.56. this observation. Arguments for both installation art and installation of art can be applied to the work thus supporting the complications that exist with defining developed constructs for installation. The considerable history of installation and the generic use of the term within contemporary practice has established the artform if somewhat difficult to define, as an integral part of gallery and museum exhibition and display. As the term installation becomes more widely used and definitions continue to change there exists the notion that it is impossible to differentiate between installation art and installation of art as the characteristics of installation have become more flexible, and the term has evolved as all encompassing.