Chapter 2 - FacStaff Home Page for CBU

advertisement

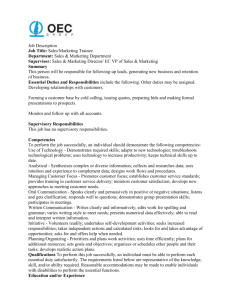

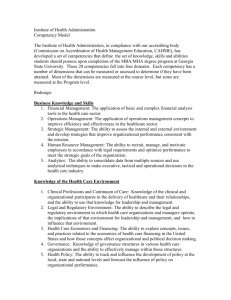

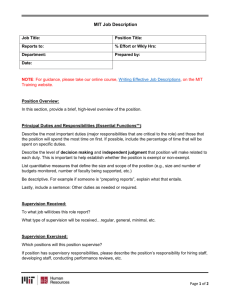

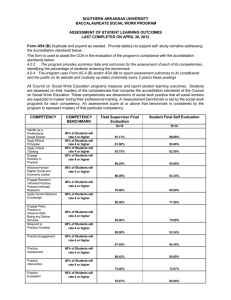

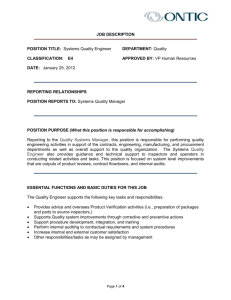

Chapter Two Job Analysis In this chapter, we’ll be looking at how we gather and organize information about the jobs in our organizations – what people do and the skills needed to carry out those responsibilities. What we’ll be looking at in this class is, first, the nature of jobs themselves – what is a job, what is a position (and is there a difference?), and how can we classify jobs. Our second objective is to develop techniques for gathering information about jobs in a methodical fashion and storing and communicating that information in an effective manner. In the course of this chapter, we will answer these questions: What is job analysis? Why do we want to analyze jobs? What are the elements of job analysis? Where do we obtain job analysis information? What is a job description and how do you write one? What is Job Analysis? Let’s start out with some definitions. This area of HR isn’t one that’s familiar to most people, so it’s a good idea to get the terminology clear first. Job analysis is: “…the systematic process of collecting relevant, work-related information related to the nature of a specific job” The folks who spend their lives thinking about job analysis (yes, there are people like that) tend to get into arguments about what JA is or isn’t and the philosophical underpinnings of the whole process. For our purposes, though, we just need to know a few important things. Job analysis is systematic; we gather comparable information about every job in a planned manner. Our goal in JA is to gather the information needed for the HR applications we discussed earlier, and to deliver it in a form that is usable for those applications. Job analysis includes only relevant work-related information. We aren’t (at this point) interested in the people performing the job. We are interested in the job itself. Our first goal is to describe the job the way it actually is. Not the way we think it will be when we get some better people. Not the way is would be if the department were fully staffed. Not the way it used to be. We describe the job at the level of satisfactory performance – the level of performance we pay people to deliver, not the level of performance we give incentives for. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 2 Job analysis describes specific jobs, jobs that actually exist1. The level of analysis is the individual job. We are describing the job “Accounting Clerk,” not all clerical jobs or all finance-related jobs. We do classify jobs into categories or families (more on that later), but each job is still described individually. Job Descriptions A job description is a brief, factual picture of the duties and work activities included in a job, the skills needed to perform those tasks, the scope of the job, and the working conditions associated with the job. Several important points to remember are: The job description should be a summary of the job, rather than a detailed set of procedures for performing the job. The level and amount of detail is, in part, dependent on the purpose JA information is used for and the organization’s practices. For example, U.S. government descriptions tend to be extremely long – up to 10 to 12 pages. One local organization (Federal Express) goes in for very short descriptions – usually one page. The average or normal length is usually 2 or 3 pages. This is another case of “it depends” – the level of detail necessary does depend on the purposes and the setting. The job description should be long enough to be informative, and short enough to be usable/ Job descriptions should contain facts, not opinions, although it is probably impossible to avoid the use of individual judgment. The purpose is to describe the job, not the employee currently performing the job Too often, you see job descriptions in notebooks, in HR or in a manager’s office, untouched and with an inch of dust across the top (housekeeping doesn’t dust them because the shelf the notebooks sits on is too high for their stepladder to reach !). These are useless. In fact, they may be worse than useless, since people think there might be valuable information in those notebooks. Keep the descriptions where you can see and use them. Update the descriptions when jobs change, and review and revise every 3 to 5 years anyways. Even if there are not major changes in a job, small changes can creep in, and over that 3 to 5 year period, the job could be significantly different. Why Job Descriptions? Job descriptions have a bad reputation. Many employees and managers see writing descriptions as a waste of time – until they need the information. Others feel that job descriptions are too confining, that they limit people to a specific set of tasks – not necessarily. Job analysis is the part of HRM that everyone loves to hate. Why? People give various reasons for not wanting to do (or even be involved in) job analysis: “It’s too much work, and I don’t have the time.” “It’s a waste of time – my people know what their jobs are.” There is a form of job analysis called “futures-oriented job analysis,” where the purpose is to describe jobs that will exist in the future (but don’t exist yet), but that is far beyond the scope of anything we can cover in this class. 1 Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 3 “Our jobs change too fast to write descriptions.” “A job description is too confining – I want my people to be flexible.” However, the information we obtain from the process of job analysis is essential for the majority of the HR functions. The manager who doesn’t have time to work on job descriptions today certainly doesn’t have time to defend against an EEO suit next week. Maybe your current people know what their jobs are – but what happens when someone suddenly quits, and you don’t have the information HR needs to start recruiting a replacement? If your jobs are changing rapidly, it’s even more essential to know what skills are needed to perform the job, since you’ll be constantly training people. Flexibility is good, but, ultimately, you do need some level of responsibility and accountability. Thus, for all human resource applications, the information we need about jobs includes tasks, job skills, and other characteristics of the job. Thus, the job description should include information about the duties the employee performs, the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to perform those tasks, and any other jobrelated information. Planning Let’s say that you’re trying to plan for future staffing needs. What jobs will people be doing 5 years from now? What skills will you need in your workforce 5 years from now? You may need the same skills, just in different mixes and proportions. You may be looking at large-scale change. In either case, job analysis is your starting point. EEO In order to ensure that all individuals are treated fairly in the workplace (including hiring, pay, training, and other conditions of employment), we need to ensure that we are making decisions based on job-related qualifications. If we are hiring a plumber, we need to make sure the person hired can run pipe and has a license to do so. And, in order to make sure that we are hiring people based on job qualifications, we first need to figure out what those needed skills are. Staffing Leaving the issue of EEO aside, no organization today is in a position to hire people who don’t have the necessary skills – nor are they in a position to overlook sources of talent because of their gender, skin color, or other irrelevancy. Not just skills matter – we need to know what tasks or responsibilities are included in the job – if nothing else, how do you recruit a candidate without telling that person what the job is? Training Well, if we want employees to acquire new skills, we need to invest in training – and you aren’t going to be very effective or efficient in training employees without knowing what job skills are needed – both for current jobs and for jobs that may exist in the future. It’s also helpful (as we’ll see later) to look at the tasks that are performed, not just the skills. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 4 Pay To determine levels of base pay for jobs (that is, the component of pay not dependent on individual performance), we need to know tasks and skills, to have a basis for determining the worth of jobs in the organization. Performance Appraisal and Management It’s extremely important to have mechanisms in place for measuring employee performance, in order to reward those performing above standard, and to help those performing below standard to improve. But, we don’t know if someone is doing a good job or a bad job until we know what the job is. The Elements of Job Analysis Before looking at what makes up job analysis, we need to clarify the unit of analysis – that is, what exactly are we looking at? The important distinction here is the difference between a position and a job. Position vs. Job One distinction that we need to make here is between a “position” and a “job.” In normal usage, these terms are interchangeable. However, in JA, the two terms have distinct meanings. Why does it matter? We said earlier that job descriptions were generally brief and did not get into very Clerical Jobs fine detail. Thus, you might write a job description for the job of social worker. Secretarial Accounting and Shipping and The precise details of the job will be and Reception Bookkeeping Warehouse different, depending on where the Teller Bookkeeper Budget Clerk person works (say, city versus rural) or the type of client the social workers Susan Smith Ann Green Ed Jones Purchasing Human Resources Maintenance specializes in (children, the elderly, or even no specialization). Do you write Determine total amount Verify and pay invoices Calculate employee of monthly insurance premiums from temporary agencies wages from timecards descriptions for positions or for jobs? That’s a good question, without a good answer. Look at how much difference there is between positions. Think through what would be more useful – more detailed descriptions or fewer descriptions. We’ve said that JA information needed to be presented in a useful format. It’s always helpful, no matter what kind of information you’re working with, to have categories or groups. For example, you put all of the computer manuals on the same shelf, and don’t mix them up with the cookbooks. It’s easier, then, to find what you want, whether you face the Blue Screen of Death or the need for double chocolate brownies. The same holds for JA. Grouping jobs together makes sense, too. It’s often more efficient to work on writing descriptions for similar jobs all at the same time, rather than jumping back and for the between clerical and management jobs, or plant jobs and sales jobs. Here’s an example. We start at the top with a broad family of clerical jobs. These are different from management and supervisory jobs, and different from professional jobs. It’s not where the jobs are located, but the type of tasks performed. For example, the VP of Accounting, a CPA, and a budget clerk all work in Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 5 an accounting department – they all work with financial data – but the type of duties each performs is different. Administratively, there are differences – the clerical jobs, for example, would receive overtime, while the professional and management job families would not. Then, we move down to a particular kind of clerical job, Accounting Clerks. These are different from secretaries and receptionists, and also different from shipping clerks and receiving clerks. However, these jobs are similar and can administratively be handled in a similar manner– for example, all of the accounting clerks would probably benefit from training in how to use a spreadsheet. The next level takes us down to various jobs in this classification. A teller is different from a bookkeeper and from a budget clerk, no matter how specific duties might differ among the three different jobs. In selection, we might look at different tests or other procedures for the different jobs. For example, we might want a teller to have some customer relations skills we don’t need in budget clerks – so the interviewer would ask applicants for these jobs some different questions On the next level, we get to specific positions. We have bookkeepers in three different departments here, one in purchasing, one in human resources, and one in maintenance. These folks will perform somewhat different duties, of course. Susan Smith in purchasing will deal with invoices and the associated paperwork. Ed Jones will calculate costs for various projects and may also deal with invoices. Ann Green has a different set of duties. Performance expectations might well differ between these positions. A payroll clerk would be expected to be 100% accurate, but we might tolerate more errors from the clerk in the maintenance department, where quick responses might be more important. On the lowest level, we see specific tasks – Ann Green does occasionally handle invoices, but also processes payroll and benefits. So, as you can see from the diagram above, there’s a hierarchy of information, moving from the very general to the very specific, from broad job category to specific duty or responsibility. Job Analysis Information What information do we need in job analysis? There are several types. Typically, JA gathers information about what people do, their job responsibilities or duties – what we’ll refer to as tasks. JA also looks at what people have to have to perform the job – what we calls KSAO’s (we’ll get to this in a minute), also called “skills” or “job skills”. Often, though not always, we look for other information about the job – physical demands, the level of responsibility and effort involved, and other contextual data. JA can also be used to gather examples of performance behaviors, but we’ll hold off on performance until later in the class. Job Tasks The basis of job analysis is the task statement. A task is a job duty or job responsibility. Some examples of tasks: Provides information to patient or patient family members regarding diagnostic or care procedures or surgery. Maintains and repairs warehouse equipment, such as forklifts and pallet jacks. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 6 Determines caller needs and refers call to the appropriate department. Makes work assignments to employees and follows up to ensure work is completed on a timely basis. When looking at a task statement, we need to ask three questions: Does the statement tell what the employee does? Does this statement tell how the employee does it? Does this statement tell why the employee does it? Some examples: What Sorts To Whom/What correspondence, forms, and reports Why to facilitate filing them How alphabetically What Organizes and files To Whom/What various materials such as position descriptions, questionnaires, computer printouts and transaction documents Why to maintain master books, examination, class and agency files Writing Task Statements Since task statements are written to represent job tasks of varying complexity, you should expect to have statements of varying complexity and length. Even though the length and complexity of the statement may vary, each statement should answer the questions "What," "To Whom/What," "How," and "Why." Frequently, the "How" and "Why" portions are so obvious and generally understood that including it would make the statement appear trivial. An optimum style to be followed in writing task statements should be consistent with the following basic rules. Style A terse, direct style, using the present tense, should be used. Terse. This means short and concise. If your word processing grammar check tells you the sentence is too long, you should have stopped a while ago. Don’t go to the opposite extreme, though, and skim over essential information. Be specific, not vague. You need to tell the reader what the person does. For example: Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 7 Determine whether or not to purchase new equipment. Too vague Conduct cost-benefit analyses to determine the productivity and efficiency payoff of purchasing new technology, updating existing equipment, purchasing Just right additional equipment, and so forth. Action Verb The statement should start with a functional or action verb that describes an action required of the individual. Identifying the job operation and selecting the verb to represent the content is a critical decision. This aspect of writing is perhaps the most difficult part of the entire process. It requires close attention and careful thought. It’s impossible to overemphasize this principle. Write about what a person does, as specifically as possible. As you can see from the above example, you can write statements to describe management work – it’s a myth that these jobs are “too vague” or “too much judgment is needed” to have precise descriptions. For example: Compiles and distributes weekly suspension lists. Maintains and repairs warehouse equipment, such as forklifts and pallet jacks. Task statements normally should not include multiple action verbs unless the several actions are invariably performed together. For example: Prepares material lists and obtains parts and materials for the installation, assembly and repair of electronic equipment An alphabetical list of sample action verbs is in Appendix A to this chapter. Specificity Task statements are intended to reveal differences among jobs. Statements that are so broad or general that they would not differentiate between jobs should be omitted, expanded or broken apart as two or more statements. Statements that refer to only a few jobs should be retained if they satisfy other standards. As a general rule, the usefulness of job description information is proportionate to the degree of specificity -- more rather than less information is needed. Whole Task Each item should refer to a "whole" task that "makes sense." That is, a sequence of acts that are invariably performed by a single employee as a continuous activity should remain intact. A sequence of interrelated activities leading to a single product or accomplishment of a single goal should not be separated. For example: Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 8 Evaluates written care plan and the patient's responses to nursing interventions on a continuous basis; reassesses short-term objectives; initiates discharge planning based on the evaluation process. Language Statement terminology and vocabulary should be at the level of the intended users. Cryptic abbreviations and unique or purely local slang terminology should be avoided. Keep the writing at a simple level. Be careful with acronyms, technical terms and jargon. Most folks know what a LAN is (Local Area Network). But, does anyone outside of FedEx know what LEAP means? Commonly used occupational terms should be used but note that some such terminology becomes rapidly obsolete. Generally, the higher the required reading level, the greater the difficulty persons will have in using the job description. Who? You should ask who is doing this action? The answer to this question provides the implied subject of the task statement. The subject is understood to be "the employee" -- taken to mean collectively, incumbents in the job being analyzed. What? You should ask what is the action? The answer to this question provides the action verb, representing the job question, and first word of the task statement. The verb used should be unique, descriptive of the action, as precise as possible and written in the present singular. For example: Select a foster care placement considering the relevant characteristics and needs of the client, and strengths of the family or facility. Object? Ask who or what is the object of the action. The answer to this question provides the object of the task statement and reflects the recipient (whom/what) of the employee’s action. Why? Ask why it is being done. The answer to this question is sometimes preceded by the phrase "in order to" and provides the reason for the action. Care should be taken to insure that "Why?" is not mistaken for "What is the action?" If the "why" is obvious, then this portion may be omitted. How? Ask how is the action done? The answer to this question is worded to indicate what guidelines or instructions, tools, equipment, or general job knowledge are used by the employee in performing the task. Frequently, the how is obvious and is thus not stated. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 9 Some Final Suggestions After answering these questions, all that you will need to do in order to write a task statement is to organize the answers into an easily readable, grammatically correct, concise sentence using the standard format described here. A final suggestion to the person who is writing task statements: Be sure that the results section ("Why?") is compatible with the verb used. For example, one does not "read a variety of materials in order to make a decision..."; one "reads a variety of materials in order to gather information..." and then one "analyzes information in order to make a decision...". One of the most common flaws in writing task statements is to include extraneous material characterizing performance standards, work setting conditions or the necessary job skills for task performance. Evaluative terms and phrases such as punctuality, attendance, diligently, carefully, competently, knowledgeably, diplomatically, under adverse conditions, etc., should never be incorporated in task statements. That type of material -- job performance standards -- applies to the employee rather than the job and should be examined separately. Complex Tasks There’s no reason why we can’t write tasks describing complex jobs, contrary to what some think. It’s simply a matter of thinking through what the job entails and using specific, behavioral language. Stay away from vague generalities, such as “manages,” “oversees,” or “administers.” Some examples for management jobs: Review the organization structure (e.g., reporting relationships, responsibility flowcharts) of a work group or division to ensure it supports the business vision and strategy. Investigate culture, education, and business training variables to determine the feasibility of delegating management functions to foreign nationals. Develop and/or administer corporate giving policies (i.e., relating to charities, fundraisers, donations to foundations) designed to promote goodwill and create a sense of positive corporate citizenship. Develop advertising or promotional strategies designed to attract customers, compete successfully with other comparable businesses, promote company image, build employee morale, and so forth. For social service jobs: Investigate prospective living facilities for client populations (i.e., children, senior adults, etc.) to determine suitability for client placement. Prepare a file and affidavit and petition to remove child or adult at risk from the home or when the family has violated the terms of the ISP. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 10 Conduct parenting skills assessment to determine strengths and weaknesses focusing on disciplining techniques, child supervision practices, drug and alcohol use, nutritional needs, school and education practice and emphasis. Conduct a work and training assessment of currently homeless prospective clients to determine their eligibility for benefits and to establish their accountability for receiving benefits. Specifying Job Skills and Minimum Qualifications When you have finished preparing task and duty statements, the next step in the process is to derive and describe the skill requirements for those tasks. Terminology here can be confusing. The correct term for what the person has to have to do the job is KSAO’s, or knowledge, skills, abilities, and other qualifications. What is confusing is that the term job skills is often substituted, as a convenient shorthand (and easier than explaining KSAO every time !!). I’ll try to be careful while we’re talking about job analysis, but in subsequent parts of this class, when you see “job skills,” remind yourself it’s really KSAO’s. Basic job requirements, such as possession of a license to practice a specific activity -- such as practicing law, driving, nursing, or boiler room operations -- should be listed first. Normally, this is a matter of legal requirements and it should be obvious whether or not a specific requirement should be listed. Writing a skill statement does not mean just attaching the words “skill” to a task statement. It’s not difficult, but there’s a bit more to it. Job skills can be categorized into three general areas and are defined as follows: Knowledge Knowledge is the foundation upon which abilities and skills are built. Knowledge, as used in writing knowledge, skill or ability statements, is defined as an organized body of information, usually of a factual or procedural nature, which, if applied, makes adequate performance of the job possible. Knowledge is learned. It should be noted however, that possession of knowledge does not insure its proper application. Knowledge is something that is learned, but don’t forget that having knowledge doesn’t mean that it can or will be used. You or I could memorize a textbook on sales techniques, yet not be able to sell ice in July in Memphis. It can be helpful to specify how the knowledge would be acquired – this is a useful guide for selection, because it tells you what to look for to determine if an applicant might have that knowledge. Some typical knowledge statements might be: Knowledge of rules of spelling, grammar and punctuation as might be acquired through graduation from high school Knowledge of consumer loan requirements, policies and procedures as might be acquired through 2 to 3 years' branch banking experience. Knowledge of blueprint reading, sheet metal work and mechanical, plumbing and electrical drawings as might be acquired through trade or vocational school training or military training. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 11 Knowledge of training and education concepts, principles and methods as might be acquired through 2 to 3 years' experience in training or adult education or 2 years' college-level work in education or training. Knowledge of warehouse layout and product locations as might be acquired through a brief period (2 to 3 weeks) of on-the-job training. Knowledge of nutrition and basic diet therapy as would be acquired through completion of Certificate in Food Service (1 year program) or completion of A.A. program in Dietetic Technology (2 year program)2. Skill Skill is defined as the proficient manual, verbal, or mental manipulation of people, ideas, or things. A skill must be demonstrable and a skill is normally acquired or learned. “Skill in operating computer peripherals” is a leaned skill, while: “Skill in distinguishing between problems which can be resolved through routine procedures from those that require specialized response or attention of other persons” implies a level of judgment that may not be something one could learn. Also, with a skill, proficiency is implied. Knowledge of sales techniques doesn’t mean that they will be used; “Skill in persuading customers” implies that the individual actually can persuade people to buy something. When writing skill statements, you may want to think about a sequence of statements, reflecting different levels of skill. You could, for example, write statements ranging from “Skill in performing simple arithmetic calculations (adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing),” up to “Skill in performing calculations, involving algebraic formulas, statistical formulas or complex procedures used in handling business data.” Some examples of skill statements would include: Verbal and written communications skills, including skill in communicating with all levels of management, vendors, and customers. Skill in making the arrangements, scheduling and completing other details for meetings Skill in operating computer peripherals such as printers, tape and disc drives, etc. Possession of supervisory skills as would be acquired through completion of an in-house supervisory training program or 2 to 3 years supervisory or management experience. Ability Ability is defined as the present power to perform a job function, to carry through with the activity while applying or using the associated essential knowledge. An ability is usually something someone has, though some knowledge may be necessary to fully use the ability. For example, “Ability to explain or demonstrate work techniques, safety procedures, etc. to others” requires the ability to communicate, but implied here is the knowledge of what is to be communicated. 2 Note here that the job skill may be acquired in more than one way and that either is acceptable. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 12 Some examples might include: Ability to organize tasks and maintain control of work flow. Ability to perform basic arithmetic calculations as would be acquired through completion of high school. Ability to work without close supervision and to exercise independent judgment. Ability to read and follow written instructions as would be acquired through completion of high school. Ability to operate standard office equipment. Ability to lift and move patients up to 250 pounds. Other Requirements A fourth category may occasionally be included, "Other Requirements". Here would be included minimum requirements not fitting into the above categories, such as: Color vision Normal eye-motor coordination, manual dexterity, visual perception (including color vision) and hearing. Vision and hearing may be corrected to normal range by corrective lenses or hearing aid. Microsoft Certified Database Administrator (MCDBA) credential. Possession of current CPR certification. Possession of a valid driver's license. Writing Skill Statements Determining the required job skills is considerably more difficult than the task portion of the analysis, in that the content is not directly observable and is "known" only through inference. The important point to remember is that job skills required for a particular task are based on your judgment and inference. On the surface, the identification and definition of job skills is deceptively simple. For lower level jobs, the inference is usually fairly obvious and the job skill frequently takes the form of a duty-based statement. As tasks become intangible, abstract or complex, the inferential step becomes greater. The job skill analysis is usually accomplished by examining each job task to determine the required skill(s). When performing this activity, it might be helpful to keep the following questions in mind: Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 13 Think of the characteristics of good and poor employees. How do good and poor employees differ? Why can some employees perform (name of task) better than others? Recall incidents or concrete examples of effective and ineffective performance by employees in the job. Then try to think of the particular skills or lack of skills that were the cause of each example. What does a person need to know in order to (name of task)? Think of someone you know who is better than anyone else at (name of task). What kind of knowledge, skills and abilities would you want that person to have? If you are going to hire someone for no other reason than for them to (name of task), what kind of knowledge, skills and abilities would you want that person to have? What kind of prior training or experience is needed to be effective in (job)? Why is that training or experience needed to make an individual qualified to do (name of task)? Remember, also, that there is not necessarily a one-to-one correspondence between tasks and skills. A particular task may require multiple KSAs, and a single KSA may be required for more than one task. Let’s take a short task statement and see how this works. Conduct employee disciplinary interviews. The skill needed here isn’t just “Skill in conducting…”. In fact, there are several skills needed here, that might include: Skill in conveying information in a concise fashion without losing necessary detail. Skill in distinguishing between effective and ineffective procedures or job performance. Skill in communicating evaluative judgments and descriptive comments on the job performance of subordinates. Skill in coaching subordinates to correct ineffective work practices or to remedy performance deficiencies. There are eight main points that may assist you in writing good job skill statements. The style recommended for writing job skill statements generally follows that for writing task statements. In addition, though, the following points should be kept in mind: Avoid simply restating a task or duty statement by attaching the word "Skill" or "Ability". So-called "duty based" job skills usually pertain only to low-level jobs. For higher-level jobs, a duty based job skill would not provide the information needed to develop the desired content for the application procedure. Each statement must represent a unique job skill. Do not combine separate and different types of job skills into composite statements. As a general rule, if you suspect that separate facets exist, write two separate statements. Job skill statements should describe a component of individual difference or variance. The degree of possession of proficiency is a measurement and decision making issue. Terms such as familiarity, mastery, or recall are inappropriate adjectives for job skill statements. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 14 Statements must represent specifically defined job skill content. Use of trait references -- such as "enthusiasm" or "patience" for the content description in the statement is inadvisable. The statement should contain enough detail to facilitate the choice of measurement method and the nature of the individual difference or variation. Think behavior – rather than specifying “tactfulness,” try “Ability to provide employee feedback in a constructive manner.” Each statement should constitute a feasible unit of measure. That is, it should be possible to write one or only a few objective statements that will measure an employee’s degree of possession of the job skill. Another reason to avoid trait references – they are much more difficult to measure. Maintain a reasonable balance between generality and specificity. Exactly how general or specific a statement should be stated is a matter of individual judgment. However, when in doubt, be more rather than less specific. Avoid the error of including trivial information when writing the items. For example, for a supervisor's job, "knowledge of how to order personal office supplies" would be a trivial item. However, because the omission of key job data is a more serious error than including trivia, include items if they are borderline examples. When possible, statements should include the source of the job skill -- graduation from high school, completion of an approved over-the-road truck driver’s training program, etc. Finding Job Analysis Information We’ve talked about the type of information that is gathered – now let’s look at where we get the information. There are a number of possibilities. Observation. The simplest way to find out what somebody does is to watch them. You could spend a day or two following a person around – and even trying to do some of their job. It’s harder than you’d think to stock a display rack with packages of pantyhose. You might have less time to observe, which may not matter – sewing shirts in a garment factory is, unfortunately, a job that you can see all of very quickly, since the employee does the same thing over and over again all day long. Some jobs, though, can’t be observed. What a manager does isn’t something that you can watch. In other cases, it just isn’t feasible to observe. For example, security reasons prevented me from seeing what a trained bodyguard in a government agency actually does. However, even in these situations, walking around the facility gives you some sense of the background and context. The heavy responsibility attached to the job of the manager of a magazine printing plant made a lot more sense after walking around the factory and seeing the massive and obviously expensive and very complex equipment. Interview. Interviews are the next most direct method. Who should be interviewed? One school of thought is that job incumbents (the people actually doing the job) are the best sources of information about what they do, while supervisors have the best insight as to what job skills are required (since supervisors have to select and train people to do the job). Others recommend interviewing only incumbents, or only supervisors. What is more important is to pick interviewees who have performed the job (or supervised it) long enough to know it – at least several years, and more is better. Pick individuals who are good performers, but be careful not to confuse their level of performance with what the job really requires. Before you go out to interview, look through whatever materials you do have, to get a rough idea what the job involves, so you can follow the interview intelligently. Listen and take notes. Ask questions if you don’t understand. A good interview will take a minimum of an hour. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 15 Finally, try to interview more than one person for a particular job. If possible, have more than one interviewer. Why? Just by chance, one interviewer will often pick up things others will miss. But, more importantly, different interviewers bring different perspectives and will pick up on multiple aspects of the job (e.g., Morgension & Campion, 1997; Prien, Prien & Wooten, 2003). For example, in a job analysis of a sales merchandiser job, three analysts were used. The sales merchandiser, basically, is the person who delivers product to a retail store and manages the displays; in this case, the sales merchandisers delivered pantyhose. All three interviewers accompanied the sales merchandisers as these folks went about their daily work. The first interviewer had recently undergone his sixth laparoscopic knee procedure -- he was the only interviewer who picked up on the amount of bending and stooping required in the job. The second interviewer had recently finished a project with sales representatives. This interviewer reported more contact between the sales merchandisers and store management, where the sales merchandiser encourages store managers to increase the space available for product – basically, active selling. The third interviewer (and the only woman) was the only one of the three interviewers who actually picked up a package of pantyhose to look at them. This interviewer was the only one to notice that the sales merchandisers placed product on the shelf according to color coding on the packages (rather than having to read the description) – thus, one job requirement turned out to be color vision. One caveat. Interviewing takes time and isn’t cheap. Questionnaires. There are various types of questionnaires. We’ll look at an open ended questionnaire, where the individual writes down what he or she does. This is similar to the interview, in that the person decides what to tell you. It’s more efficient, though at the possible cost of losing information (what people forget or take so much for granted that they don’t include it). Questionnaires can also take the form of checklists – this is a list of task and skill statements (often several hundred), and the respondent indicates how important each is to the job. These are time-consuming and expensive to develop, and you need professional guidance. This type of questionnaire is best suited to a job where there are a very large number of incumbents -- police officers, sales clerks, etc. Your Filing Cabinet. Don’t overlook information you already have, such as old job descriptions, policy and procedure manuals and job descriptions prepared by trade or industry associations. Other materials about the general occupational area can be useful - -for example, when writing a job description for an audiologist, my first stop was a pamphlet I picked up in a waiting room, entitled “Your trip to Hearing Testing”. O*Net. One final source for job analysis information is the Occupational Information Network, or O*Net [www.online.onetcenter.org]. This is a database, sponsored by the US Department of Labor, that aggregates information about more than 1,100 (to be precise, 1,167) different jobs. For each of these jobs, O*Net provides information useful for job analysis and for other HR applications, including the following: Tasks performed Required knowledge, skills and abilities Work activities (general categories of job responsibilities) Work context (description of level of responsibility, working conditions, contact with other people -- this information is essential for wage and salary decisions, as we’ll discuss later) Required amount of education and/or experience Occupational interest categories (the Holland taxonomy of career interests, which we’ll discuss later on) Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 16 Work styles (personality variables) Work values (motivating factors, such as achievement, relationships and independence) Related occupations Median annual wage, number employed, and projected employment growth The drawback, of course, is that the occupational list, though extensive, cannot represent every possible job, nor can the descriptive material be more than very general. Nevertheless, it’s a starting point, especially if you’re faced with writing descriptions for jobs that you are unfamiliar with. Format for the Job Description In this section, we will look at a standardized format for job descriptions that may be used in most organizations. Since every organization is different, the format described below may need to be added to or changed. However, the basic elements will remain constant. Note that a good job description is complete, yet concise, generally 2 to 3 pages in length. A description much shorter than 2 to 3 pages may be overlooking essential information. Longer job descriptions generally include so much detail or trivia as to be cumbersome and useless. Refer to the sample job description (found in the Appendix) while reading this section. Identification In this section of a job description, some basic identifying information is provided so that those people in the organization using the job description will know what job is being described. Job Title Here is listed the job title as it is found in personnel records, such as: Branch Manager Clerk A Loan Officer Medical Technologist HVAC Mechanic Social Worker II Senior Accountant Packaging Technician Note that many titles have qualifiers – “Senior,” “A,” or “II”. This is a common organizational practice, and indicates that the jobs follow a progression – it’s helpful, though not essential, to coordinate the descriptions for these jobs, to ensure that the progression, in terms of progressively more complex work, is as you want it. Also, it is acceptable (and probably advisable) to add a word or brief phrase to that title to further identify the job, either by department or within a department. Most organizations attempt to keep the number of Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 17 separate job titles within the organization to a minimum. However, the same job title may contain a number of different positions. That is, an organization may have a number of positions titled “Clerk A”, all of whom perform similar tasks and who each require approximately the same skills, but whose specific job descriptions do vary somewhat. For example, the Loan Officer (Automobile) obviously makes loans, as would the Loan Officer (Real Estate) or Loan Officer (Commercial), but the specifics of the job – the precise tasks, and possibly some details of the skills – will vary. Some examples: Branch Manager - New York Branch Office Clerk A - Payroll Loan Officer (Automobile) Medical Technologist - Blood Bank Job Family In most organizations, jobs are assigned to large categories or job families. These are made up of jobs that are similar to one another and which are convenient to administer together. A sample set of job family categories is as follows: Supervisory/Administrative/Management Professional Technical Service/Support Job Code and Salary Grade In most large organizations, jobs are assigned an alphanumeric code for convenience. Jobs are also assigned to salary grades. Both pieces of information should be included in the job description. Supervisor An additional identification of jobs in an organizational unit is the supervisor's title -- not the current supervisor's name. Unit and Department This would be the location of the job within the organization. This can be the department or division, or it may be a physical location. Provide enough information so that the reader will know where the job is located, though it isn’t necessary to give the exact cubicle location. For example: New York Branch Headquarters - Human Resources Retail Banking Division Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 18 Suburban Hospital -- East Job Summary The job summary is a brief statement giving the purpose of the job and its major responsibilities. It should be, at most, one to two sentences long, but should include enough information to distinguish this job from other jobs. The job summary should tell the reader the job's purpose; that is, why the job exists. Why do we hire someone for this job? This part of the description is critical, and is often the last part written. This is the information that will often appear in your recruiting material or job postings. This is a short statement – the example above is as long as you need to get – and tells the reader why the job exists. Basically, why do we pay people to come in and perform this job? For example: The Journeyman Plumber is responsible for inspecting, testing, repairing and performing preventative maintenance on all plumbing equipment and systems at all facilities in Memphis, in accordance with local, state and national codes and standards. Duties and Responsibilities In this section, the major duties and responsibilities assigned to the job are listed. Normally, most jobs can be summarized in 10 to 12 statements. More than that, and you run the risk of including trivial information. Writing the duty and responsibility statements has been discussed in more detail earlier in this chapter. However, one task or duty statement that is always present: “Performs other duties as required.” Including this statement gives managers and supervisors the flexibility to add to the stated duties as necessary (though, of course, within reason). It is useful, though not essential, to give some indication of the amount of time spent on different tasks. It isn’t necessary to keep a detailed diary; rough estimates are sufficient. Interpersonal Relations In this section of the job description, the job incumbent's contact with other individuals is described. This information, although it does not fall into the strict categories of “task” and “skill” that we’ve discussed, is essential for providing a context for how tasks are performed. Later, when we are looking at how to pay employees, this information will allow us to judge how much responsibility is part of the job. The type and frequency of contacts should be indicated. For example, contact may be "daily", "frequent" or "occasional". Contacts may be "routine" or the employee may "represent Deficit National Bank to the news media". There are two types of contact, internal and external. Internal contacts are those interactions with other employees within the department, work group or organization, such as supervisors and other employees. External contacts are with individuals outside the organization, such as customers, suppliers, community organizations, competitors, etc. For example: Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 19 The Press Operator has daily contact with other employees in Printing Services and in other company departments who are requesting work to be done. These contacts are often for the purpose of resolving problems. The Press Operator has occasional contact with service representatives who are repairing equipment. Supervision Given/Received Here, we are looking at the type and nature of the supervision given and received. Again, this information provides context, as well ad a way of assessing how much responsibility the job is assigned. If the job is not assigned any supervisory responsibilities, this should be noted. There are no supervisory or lead responsibilities assigned to this job. Some jobs are “staff” jobs, and require that the incumbent provide advice or consultation to others: There are no supervisory responsibilities assigned to this job, except that the incumbent is expected to provide professional and technical advice and consultation. If the job does include supervisory responsibilities, the number and type of employees supervised and the type of supervision should be indicated: The Manager – Payroll directly supervises 2 clerical and 3 professional employees. The Project Manager – Web Design supervises 3 professional employees during projects, but does not have authority to hire, terminate, discipline or complete performance evaluations without Department Manager's approval The Master Electrician is under the general supervision of the Supervisor - Building Maintenance. The job is a lead job: the incumbent will assign duties to technical and service employees in the area and will provide input to personnel actions. The Branch Manager – New York directly supervises 1 clerical and 2 supervisory employees and indirectly supervises 12 clerical employees. The type of supervision received should also be indicated: Close supervision General supervision "Under the Department Manager's professional guidance" The task statements (as discussed later) should, when appropriate, give some indication of the type and level of approval the employee needs to make decisions or take action: Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 20 Interviews and hires employees to fill vacant positions as indicated by theVice President Finance Physical Demands/Conditions In this section, the physical environment and demands of the job are described. Again, this provides context, and working conditions are an essential part, as we’ll see later, of setting pay for a job. Items to consider may include (but are not necessarily limited to): Approximate amount to be lifted or carried Frequency of lifting or carrying Frequency of travel Frequency of standing, walking or climbing Exposure to noise, infection, heat, cold or outside elements (i.e., rain or dust) Exposure to physical hazards, such as dangerous equipment Combined, we might see a statement such as: Constant walking, standing, bending and kneeling; may be required to work with hands above shoulders. Heavy physical effort and coordination needed to move or position equipment. Maximum weight normally moved, lifted and carried alone does not exceed 150 pounds. We normally think of management jobs or other “office” jobs as having few, if any, physical demands. Remember that many clerical positions may involve lifting or moving (i.e., the mail or boxes of paper). Management and professional jobs may well involve travel. This is a physical demand to be considered (ask anyone with platinum frequent flier membership !) A shift assignment may be included here if the duties assigned to the job are specific to a shift or if it is not obvious that employees in the job may be assigned to shift or weekend work. Job Skills and/or Minimum Qualifications This section may list either the necessary job skills or the minimum qualifications. The job skills would include all skills necessary to perform the job, including those skills s that an individual might reasonably be expected to acquire after starting to work in the job. The minimum qualifications, on the other hand, include only those skills necessary for an individual to enter the job. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 21 Date and Approval The final section of the job description is the documentation. This will vary, according to organization requirements, but at a minimum, this section should include the name of the individual who prepared the description, the name of the individual who reviewed or approved the description, and the date the description was prepared. Remember that job descriptions must be updated as jobs change. An outdated description is worse than no description at all. Job descriptions must be updated if major changes in the job occur. Technology may change, jobs may be reorganized, or the skills needed may change. Even if there are no major changes, job content drifts, and a 5-year old description is apt to be out of date. A New Approach: Competency Modeling In recent years, many organizations have adopted a different approach to job analysis, an approach known as “competency modeling.” Is this something new and different, or just job analysis under a new name? To begin with, traditional job analysis has always been viewed by most people as an unwanted stepchild. Human Resources is the only department interested in writing job descriptions and the people doing “real work” don’t have time for that nonsense. There’s some basis for this bad reputation; in particular, traditional job descriptions stand by themselves. That is, there’s no linkage between the job description and the overall goals of the organization. At best, the job description allows us to assess individual effectiveness, not the contribution of the job to organizational effectiveness. While there are important HR applications of the individual-level job information, something more, many believe, is needed. So, how do we get to competency modeling? As far back as 1973, David McClelland suggested that traditional aptitude and personality measures were insufficient predictors of job performance. Instead, McClelland recommended the use of direct measures of job competencies, which he defined as clusters of knowledge, skill, ability, personal traits and motivations, directly linked to outcomes. However, the idea of competencies really took off with the Harvard Business Review article by Prahalad and Hamel, entitled, “The Core Competencies of the Organization.” This article is credited with popularizing the term “core competencies,” meaning those strengths that contribute to an organization’s competitive advantage. Core competency can also be defined as the aggregation of learning within an organization, including the coordination and integration of various production skills and technologies. Core competencies by nature are general and can be applied to numerous areas, including individuals within the organization. Following from this is the idea that an organization needs to make use of its core competencies, and outsource or divest functions that don’t utilize core competencies (i.e., leveraging organizational strengths) For an organization, core competency may be, for example, Walmart’s expertise in logistics or the superb customer service delivered by Nordstrom’s. Another example is 3M’s competency in coatings and adhesives, which eventually leads to film, tape, and Post-it notes. The next step, then is to collect information on knowledge, skills, and personal characteristics associated with high levels of individual performance, as it contributes to organizational effectiveness. Furthermore, the goal of competency modeling is to provide information that can be used to support the management of people, not just the traditional HR functions. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 22 What, then, is a competency? There are a number of definitions: “A knowledge, skill, ability, or characteristic associated with high performance on a job” (Mirabile, 1997) “A cluster of related knowledge, attitudes and skills that affect a major part of one’s job” (Parry, 1998) “A description of measurable work habits and personal skills used to achieve a work objective” (Green, 1999) “Measurable, occupationally relevant, and behaviorally based characteristics or capabilities of people” (Schippmann, 1999) The key to all of these definitions is the linkage to job performance, preferably through the specification of observable behaviors linked to effective job performance. An example from 3M’s model (Alldredge & Nilan, 2000, p. 143) follows: Competency: Global Perspective. Respects, values, and leverages other customs, cultures and values. Uses a global management team to better understand and grow the total business; bale to leverage the benefits from working in multicultural environments. Optimizes and integrates resources on a global basis, including manufacturing, research, and business across countries, and functions to increase 3M’s growth and profitability. Satisfies global customers and markets from anywhere in the world. Actively stays current on world economies, trade issues, international market trends and opportunities. Developing a competency model from scratch is, obviously, very time-consuming and expensive and, thus, not always a practical option. In addition, there is already in existence a vast body of job knowledge that can be used as a starting point. However, simply purchasing and using a general, off-the-shelf model is not likely to have good results, since the linkage between individual level competencies and organizational level core competencies will not be there. 3M, for example, began with a review of leadership research, then brought in executives and senior managers, as well as HR staff (in training and development areas) to develop their model, with the goal of having management take “ownership” of the model ((Alldredge & Nilan, 2000). There is, however, a different perspective, as suggested by the US Office of Personnel Management (Rodriguez, et al., 2002). The psychologists working at OPM suggest that a shared set of competencies, at least among public sector entities, has the advantage of efficiency, but, moreover, gives different agencies and entities (federal, state and local) the opportunity to share best practices based on common model. Once you’ve made the decision to adopt competency modeling, what next? There are several approaches that an organization can take in developing a competency model (as described by Briscoe & Hall, 1999). First, there’s the research-based approach, where the focus is on describing the way things are done in the Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 23 organization today. TAP Pharmaceutical Products used this approach in their development program for sales managers. The purpose here was not to bring about change so much as to develop the next generation of managers (Otterbein & York, 2006).. The strategy-based approach has a stronger linkage to strategy, and asks a different question: “Where are we going and how do we get there?” Authors Ron Zemke and Susan Zemke (1999) give the example of the Case Corporation, a manufacturer of farm equipment. Management at Case learned that their salespeople in Europe were being expected to provide a much higher level of customer support to their customers (equipment retailers) –becoming, essentially, product engineers instead of simply sales people. The competency model was originally developed to assess current employees’ development needs, but its use was soon expanded to selection of new employees. Finally, a values-based approach defines competencies in terms of organizational culture or values. An example of this would be Southwest Airlines, whose competency-based leadership development program is based on the “Southwest Way” – “the warrior spirit, the servant’s heart, and the fun-luving attitude” (Bryant, 2007, p.39). Then, what do you do with competencies? The most common uses are for selection (including succession planning and career development), employee development (not so much training, but long-term development) and, finally, performance appraisal. Let’s look at this in a graphic format (adopted from Schippmann, 1999): Linkage to Organization Strategy and Core Competencies Finally, what is the future of competency modeling? Briscoe and Hall (1999) suggest that the next step is so-called “metacompetencies,” which they define as the competencies that allow a person to learn and acquire more competencies. They define two metacompetencies: “Adaptability,“ or the ability to learn and change “Self-Awareness”, or willingness internalize and use learning. to Competencies (Required) Work Activities Organizational Vision Spring 2008 Work Context Competitive Strategy (Core Competencies) Management 412 | Job Analysis Strategic Business Initiatives 31 Source: Schippmann, 1999) Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 24 Appendix: Sample Job Description JOB DESCRIPTION JOB TITLE: Registered Nurse - Same Day Surgery JOB FAMILY: Professional SUPERVISOR: Manager - Same Day Surgery UNIT: Suburban Hospital DEPARTMENT: Surgical Services JOB CODE: 23AGK SALARY GRADE: 23 JOB SUMMARY: The incumbent is responsible for providing nursing care to patients admitted to the Same Day Surgery Unit, utilizing the nursing processes of assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation, in accordance with professional standards and hospital standards of patient care. DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES: % OF TIME SPENT 20% 1. Assesses the patient's condition, systematically utilizing verbal and technical nursing skills, to establish a basis for patient care. 20% 2. Plans appropriate nursing interventions, utilizing the patient assessment data and formulates a written care plan, reflecting pertinent physical and psychosocial problems. 15% 3. Implements patient care activities based on written care plan, knowledge of professional nursing standards and hospital standards of patient care. Patient care activities may include administration of medications, tube feedings and changing dressings. 10% 4. Evaluates written care plan and the patient's responses to nursing interventions on a continuous basis; reassesses short-term objectives; initiates discharge planning based on the evaluation process. 10% 5. Provides technical information and assistance to physicians and other department employees; assigns duties to unit technical, clerical and service staff; coordinates patient care activities with other hospital departments such as Respiratory Therapy, Radiology and Pharmacy. 5% 6. Provides information to patient or patient family members regarding diagnostic or care procedures or surgery. 10% 7. Identifies the learning needs of patients and patients' family members and provides teaching or education to meet those needs. Documents education or teaching in patient records. 5% 8. Maintains own professional knowledge and skills by participating in formal continuing education activities. 5% 9. Performs other duties as required. Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 25 INTERNAL CONTACTS: The RN - Same Day Surgery has daily contact with employees in the same department, in other Surgical Services departments and in other hospital departments, including acute care nursing floors, Respiratory Therapy, Radiology and Pharmacy. EXTERNAL CONTACTS: The RN - Same Day Surgery has daily contact with physicians, other outside professional staff, patients and patients' family members. SUPERVISION GIVEN/RECEIVED: The RN - Same Day Surgery is under the supervision of the Manager - Same Day Surgery. There are no supervisory responsibilities assigned to this job, but the incumbent will assign duties to technical, service and clerical staff members on the unit. PHYSICAL DEMANDS/CONDITIONS: Frequent walking and standing; moderate to heavy physical effort and coordination needed to move patients or equipment. Maximum weight normally moved, lifted or carried alone does not exceed 150 pounds. Invasive patient contact. MINIMUM QUALIFICATIONS: 1. Possession of a current license to practice in the state of Tennessee as an RN. 2. Ability to understand and prepare complex written materials, such as patient records. 3. Ability to communicate verbally with all levels of employees and management, physicians and patients and their families. 4. Ability to work without close supervision and to exercise independent judgment in a professional area. 5. Ability to organize multiple tasks and projects and maintain control of own and others' work flow. APPROVED: Jane Doe DATE: SURGICAL SERVICES APPROVED: John Smith COMPENSATION DEPARTMENT DATE: Chapter Two: Job Analysis Page 26 References and Suggestions for Further Reading Alldredge, M. E., & Nilan, K. J. (2000). 3M’s leadership competency model: An internally developed solution. Human Resource management, 39(2 & 3), 133-145. Briscoe, J. P., & Hall, D. T. (Autumn, 1999). Grooming and picking leaders using competency frameworks: Do they work? Organizational Dynamics, 37-51. Bryant, E. (December 2007). Leadership development Southwest style. T & D, pp. 36-39. Clifford, J. P. (1994). Job analysis: Why do it, and how should it be done? Public Personnel Management, 23(2), 321-340. Otterbein, E., & York, J. (November 2006). Sales leadership development. T & D, pp. 55-57. Parry, S. B. (June 1998). Just what is a competency? (And why should you care?). Training, pp. 58-64. Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. (May-June 1990). The core competencies of the organization. Harvard Business Review, pp. 79-91. Prien, K. O., Prien, E. P., & Wooten, W. A. (2003). Interrater reliability in job analysis: Differences in strategy and perspective. Public Personnel Management, 32(1), 125-141. Green, P. C. (1999). Building robust competencies: Linking human resource systems to organizational strategies. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Rodriguez, D., Patel, R., Bright, A., Gregory, D., & Gowing, M. K. (2002). Developing competency models to promote integrated human resource practices. Human Resource Management, 4193), 309-324. Harvey, R. J., & Wilson, M. A. (2000). Yes Virginia, there is an objective reality in job analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(7), 830-855. Sanchez, J. I. (1994). From documentation to innovation: Reshaping job analysis to meet emerging business needs. Human Resource Management Review, 4(1), 51-74. Lahti, R. K. (1999). Identifying and integrating individual level and organizational level core competencies. Journal of Business and Psychology, 14(1), 59-75. Schippmann, J. S. (1999). Strategic job modeling: Working at the core of integrated human resources. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates.Schippmann, J.S., Ash, R.A., Battista, M., Carr, L., Eyde, L. D., Hesketh, B., Kehoe, J., Pearlman, K. Prien, E. P., & Sanchez, J. I. (2000). The practice of competency modeling. Personnal Psychology, 53, 703-740. Morgenson, F. P. & Campion, M. A. (1997). Social and cognitive sources of potential inaccuracy in job analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 627-655. Mirabile, R. J. (August 1997). Everything you always wanted to know about competency modeling. Training & Development, pp. 73-77. Zemke, R., & Zemke, S. (January 1999). Putting competencies to work. Training, pp. 70-76.