Activism and Resilience in Guatemala: Maya Intercultural Bilingual

Activism and Resilience in Guatemala: Maya Intercultural Bilingual Education

By Janelle M. Johnson

University of Arizona

December 12, 2006

Dr. William Demmert, Dr. Leisy Wyman

Introduction: State of Indigenous Languages in Guatemala

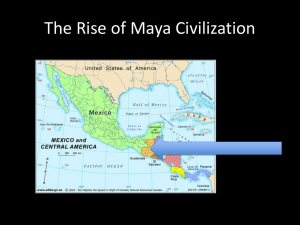

There are currently 22 Mayan languages spoken in Guatemala, along with

Spanish, Xinka, and Garífuna. Some of Guatemala’s languages with fewer speakers are endangered, but even the larger languages are losing ground in many communities.

Because of a complex combination of economic, social and historical forces, many

Guatemalans emphasize the use of Spanish with their children, and there is even a demand for English classes in schools and language academies. The decrease in agricultural jobs with the increase in factory jobs, combined with the growth of technology, tends to push people towards languages of wider communication and away from their heritage language (interview with Domingo Chovix, field notes). Tourism is one of the principle economic strengths of Guatemala—many people visit the country each year to see both the ancient and contemporary Maya communities. Although the

Maya culture is an economic draw for tourists, no tourists speak a Mayan language and many do not even speak Spanish (interview with Braulio López, field notes).

This paper refers generally to Guatemalan Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE) for the Maya population, and specifically to one school in Sumpango, which is in the

Kaqchikel language region; Kaqchikel is one of the largest Mayan languages according to number of speakers. I spent time at a Sumpango school this past summer, researching people’s perceptions of language use. The situation of the Kaqchikel Maya is reminiscent of the Navajo of the United States; “although geographically isolated, has maintained a large, intact population, many of whom speak the language. Recent research, however, has indicated that even with efforts to teach Navajo in the schools, fewer children are coming to school knowing how to speak Navajo” (Berlin, 21).

Although Kaqchikel has a large number of speakers in total, in towns like Sumpango only the eldest community members speak the heritage language.

Brief Historical Overview of Post-Colonial Guatemala

As in many post-colonial settings, the Indigenous peoples of Guatemala have faced adversity for centuries; the Maya have historically been seen as an “Indian problem” by those in power (Fischer, 52-53). Although they have not undergone largescale displacement to reservations or forced attendance at boarding schools, they have been attacked in their own homes and villages and subjected to pejorative de jure and de facto government policies. The Maya have undergone a range of different types of attacks from both extreme right and extreme left governments since the European invasion; the conservatives preferred to exclude them from mainstream society, while the liberals, acting with an attempt at benevolence, actually did more damage during the

1950’s. “The liberals envisioned a state based on the model of Europe nation-statehood, which involved integrating the Indians into Western society. An educated yet homogenous population was seen as key to political stability and economic prosperity”

(Fischer, 68). During the 1980’s, violence and friction between the main groups of

Guatemala increased, and the state tried to solve “the Indian problem” by force. The counter-insurgency military action served as justification for the Guatemalan government to attack the Maya and their culture, often violently, in order to achieve this assimilation

(Raxche’, 77). Dictators Garcia and Ríos Montt both enforced a “beans and bullets” policy. “The native populace could either accept humanitarian aid and ideological indoctrination by government forces or be subject to extermination as accessories to

treason” (Fischer, 63). The price of such assimilation includes the decrease in the use of the indigenous language, causing language shift and eventually language death (Berlin,

19).

Pan Maya movement

Continuous attacks on the Maya and their culture and language have still not achieved the state’s goal. As stated by Raxche', (87) “Today, Maya identity and culture remain strong…But we cannot ignore the enormous weight of five centuries of continuous assimilationist and integrationist policies that we have suffered.” The movement itself has been shaped by Maya values, some of which include hard work; community cooperation and support; a holistic and balanced respect for nature, elders, and a supreme being; and the awareness of one’s role in the community (Heckt, 324-325;

Raxche’, 87). These values are taught in the home and in the community, but can also be taught in the school through discussions and stories. “The teacher explained to the students what fabulas (fables) were—stories with a lesson at the end, then told the story of the boy who cried wolf. She explained about lying at home or lying at school was wrong, and then asked the kids who is always looking, even if their parents believe them.

“

Mamá

?” one child guessed. “ Jesús ?” another responded. “Sí , Jesús !” she said. She read another fabula about a lazy donkey suffering since it didn’t work hard, and then asked the kids what they wanted to be when they grew up. Responses included ‘doctor,’

‘architect,’ ‘nurse,’ ‘teacher,’ and ‘firefighter.’ She told the kids if they worked hard, studied, and put forth the effort, they could achieve those dreams” (observations, field

notes).

Such expression and reinforcement of values helps develop the resiliency of

Maya students.

Although examples of positive, transformative education can be found in

Guatemala, they are the exception rather than the rule since so many indigenous children do not have the opportunity to get an education, let alone one with culturally relevant curriculum. Private schools in Guatemala tend to reinforce the status quo and the hegemony of Ladinos. “Maya and Ladinos cannot learn to coexist harmoniously as long as the educational system remains a vehicle for reproducing ignorance of and disdain for the Maya and their culture” (Cojtí Cuxil, 41). Despite the fact that the Maya make up between 40 and 60% of Guatemala’s population, communities remain relatively isolated.

Allegiance tends to be to locality rather than to being Maya or even to the linguistic group. Maya scholars leading the Pan Maya movement “hope to unify Guatemala’s fragmented Maya groups and empower them to take a more active role in Guatemalan political and economic systems, a necessary precursor for equitable economic growth and democratization in Guatemala, as elsewhere” (Fischer, 52).

Language Activism and Schools

Learning and teaching among the Maya are often seen during the practical transference of knowledge in an apprenticeship-type setting. Groups of people commonly work cooperatively, and children observe and imitate adults, especially during important household tasks beginning at a fairly young age (Heckt, 326). At the bilingual school in Sumpango, I witnessed some teachers working in concert with these methods and some teachers utilizing more traditionally school-based methodology. The

preprimary classroom where I spent most of my time was a positive example of the apprenticeship style of instruction for certain tasks. This group of five, six, and sevenyear olds had designated jobs that rotated daily, and were not assigned by gender.

Students took turns at collecting the hot corn atol drink from the kitchen, serving the atol and snack, delivering firewood to the kitchen, and sweeping at the end of the day. “The teacher is still in the kitchen during recreo , so the kids start serving the atol and cornflakes on their own—quite impressive! Two students were serving—one ladling the atol and one dumping a handful of cornflakes into each mug, while the rest of the children form a neat and patient line” (field notes).

Adrián Chávez, considered the father of the pan Maya movement, created a

Mayan alphabet borrowing diacritics and symbols various Native American alphabets.

His system was not widely adopted, but “the idea of a unified alphabet was taken up again in the early 1970s by a team of U.S. and Maya linguists, and by the mid-1980s it had become the rallying point for the formation of the pan-Maya movement” (Warren,

89). Chávez was also the first to organize an Indigenous teachers’ conference as well as a national Mayan language conference in 1949 (Warren, 89). Unification of the alphabets and growth of a pan Maya identity was openly opposed by the Summer

Institute of Linguistics (Cojtí Cuxil, 38; England, 184). The SIL has produced a huge body of descriptive linguistic data, greatly increased literacy, and trained many Maya linguists, but their refusal to support unified Mayan alphabet actually helped to unify activists of the pan-Maya movement (Warren, 91). In a 1987 meeting, it was decided to avoid Spanish spelling conventions “based on a clear but revolutionary principle: the purpose of writing Mayan languages was to be for the inherent value of literacy in Maya

and for the promotion of writing as an extension of their domains of usage and not just as a means for teaching literacy in Spanish” (England, 183).

Indigenous language and empowerment go hand in hand in Guatemala since language has existed as a (relatively) safe means for Maya activism in Guatemala. “The uniqueness of the pan-Maya movement is most apparent in its circumspect political demands, which are much less confrontational than the ethnic politics of Eastern Europe in the 1990s. Guatemala’s period of violence was all too effective in instilling a deepseated fear of confrontational state resistance” (Raxche’, 86).

Language and cultural knowledge are transmitted formally only in the schools since that has been the extent of the reach of language policy up to this point. Some degree of corpus language planning has occurred, as seen in the IBE schools, adult language classes, and standardization of a

Mayan alphabet, but status planning has been non-existent. Bilingual intercultural education has been the sole state-sponsored cultural activity supportive in any way of

Maya culture (Otzoy, 156). Language is only one aspect of the movimiento maya ; it

“also promotes the revitalization of costumbre , or traditional indigenous practices, in terms of religious customs, sociopolitical organization, and the use of Maya dress”

(Otzoy, 159).

Over the last 20 years, IBE has contributed to the codification, standardization, and normalization of languages, as well as improvements in teacher training and education policies, but only the foundation has been laid; changing a 500-year-old system is not easy (citing Julia Richards, field notes). Indigenous Maya have fewer opportunities for formalized schooling than do non-Maya Guatemalans, and their success rate is statistically lower. Approximately one third of eligible rural Maya children attend

school, and half the students drop out during the first grade (Chesterfield, Enge, Rubio, p. 104).

Empowerment of the Maya people of Guatemala is necessary to correct such injustice. When such activism takes place and a culturally relevant, student-centered education is available, students have the best chance of success. I saw some excellent examples this summer; “The teacher has the kids in a circle, answering questions from

Kaqchikel to Spanish and Spanish to Kaqchikel. She asks them different vocabulary, and how to write different letters and symbols in the dirt. If the kids make a mistake, they have to do a little pantomime or sound the other kids will guess. If the kids answer correctly, she asks the class to applaud” (observations, field notes). In a conversation with the bilingual school director, he told me that their students’ parents had been really supportive of the school since the beginning, helping with even physical labor by clearing the muddy land. The parents generally trust the school and want to help. There is no empty room in the school, and it is continuing to grow every year—it was unfortunate that they were going to have to close their doors to new students, even though they have hired three additional teachers (interview with Domingo Chovix, field notes).

Potential Suggestions for Schools

The movement is truly a national, at times transnational, phenomenon. This is in sharp contrast to the community-based allegiances that have long characterized

Maya social identity. The movement promotes association based on linguistic groups and then, building on that base, hopes to foster a pan-Maya, even pan-

Native American, identity. By so doing it hopes to peacefully unite Guatemalan

Indians into a power base that can exert a proportional influence on Guatemalan politics and so claim social and economic justice for all Maya people (Fischer &

Brown, 15).

As stated by Maya scholars and activists, IBE in Guatemala is merely at its foundational stage. By no means do I presume to have solutions to the challenges faced by the Maya schools, but I would like to place myself in the role of an information conduit between communities. The following comments are not recommendations per se, but rather efforts or strategies that have been successful in Indigenous educational settings in other parts of the world, and which I would like to share with the Guatemalan educators who have been kind enough to work with me. I present these ideas with gratitude and deference for my hosts who were generous enough to welcome me into their community and school, with the hope that some of the information may be helpful.

One constructive beginning to this dialogue could be Demmert and Towner’s description of culturally based education’s critical points (9-10): “1. Recognition and use of Native languages; 2. Pedagogy that stresses traditional cultural characteristics; 3.

Teaching strategies congruent with traditional culture as well as contemporary ways of knowing and learning; 4. Curriculum based on traditional culture; 5. Strong Native community participation; and 6. Knowledge and use of the social and political mores of the community.”

My educational background is second language teaching, and I recognized that the methodology utilized in Sumpango’s bilingual school was a foreign languageteaching model. The students of Sumpango are nearly all Spanish L1 speakers, but many parents of the community support a Spanish/Kaqchikel bilingual education for their children. In my professional opinion, a Second Language Acquisition and Teaching model would be more effective in reaching the community’s language goals. As described by Lawrence Berlin (19), the SLAT model offers “the pedagogical perspective

that attempts to translate the knowledge produced through research…into effective and workable approaches to classroom instruction.” Mayan language can be used as the medium rather than the target of instruction, and used communicatively to teach various subjects through context-based, relevant lessons. The support and use of the language by the school provides it with legitimacy among community members, according to the

Guatemalans with whom I worked. “Studies have shown that the increased use and visibility of the language in the schools has been effective in improving student involvement as they gain a greater respect for their language and culture through the school’s validation” (Berlin, 22). The community and the school can cyclically bolster each other through the inclusion of traditional beliefs, values, and goals in the education of children (Manu’atu & Kepa, 10).

Indigenous education in Guatemala has utilized an intercultural bilingual education model; I do not believe immersion education would not be a good match for

Guatemala, since students statistically do not complete many years of school, and they do have a need to read and write in Spanish to prosper economically. After sixth grade, many of the students will work where they only need Spanish skills. Braulio described the jobs of the residents of Sumpango as largely business people and workers in maquilas , since there are several very close to town, while only a small number of people work in the fields. He said the situation has changed greatly from ten years ago, when

Sumpango’s economy centered on agriculture and the market. Prices for agricultural goods have dropped substantially, and that is the biggest reason for the changes in the community (interview, field notes).

The current model of bilingual education could be much more effective, however, in its training and support of its teachers and curricular

content. Guatemalan teachers have many challenges, and bilingual teachers have an even more difficult job, especially since so many of them are language students themselves.

“The kids are learning Kaqchikel as a second language, and school is limited as it is.

There are many days when school is not in session, or teachers are away at workshops; classes start late and get out early, and recess lasts a long time. Back in the Prepa classroom, the teacher has been using the Kaqchikel Cultura Maya and Spanish as a second language books to cut out pictures to use in classroom assignments” (interview with Alma Delia, observations; field notes).

I would advocate any possible increase in support for teacher training, professional development, and relevant classroom materials.

Regarding school curriculum, the IBE content and materials must be adjusted for communities where the heritage language is not the L1; the teachers at the bilingual school in Sumpango were Kaqchikel students themselves (interviews with Alma Delia,

Domingo Chovix, & Braulio López; field notes). A common curriculum would be helpful, but with available adaptations to meet each community’s linguistic needs; as advocated by Bo-yuen Ngai, experienced teachers should have input in the curriculum, which ideally includes cultural history, stories, ceremonies, epistemology, problem solving, traditions, customs, and natural studies (225-227). I would like to see continued development of critical awareness among both students and teachers “as part of a process by which they can come to understand more deeply possible connections between technocratic pedagogy and the political, social, and economic forces, and how their own culture can be accentuated or marginalised by the mass media, economic institutions,

[and] educational institutions of the dominant society” (Manu’atu & Kepa, 3).

Examining the hegemonic forces that have suppressed the Maya in the past and continue

to do so today would empower students, families, and communities; such activism can be a terrifying prospect for people with fresh scars and lost family members.

References

Berlin, Lawrence N. (2000 ). The Benefits of Second Language Acquisition and Teaching for Indigenous Language Educators . Journal of American Indian Education, V39 n3, p.

19-35, 2000.

Bo-yuen Ngai, P. (2006). Grassroots Suggestions for Linking Native-Language

Learning, Native American Studies, and Mainstream Education in Reservation Schools with Mixed Indian and White Student Populations . Language, Culture and Curriculum,

Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 220-236.

Chesterfield, R.; Enge, K.; Rubio, F. (2002). Cross-Cultural Cognitive Categorization of Students by Guatemalan Teachers.

Cross-Cultural Research, Vol. 36 No. 2, pp. 103-

122.

Cojtí Cuxil, Demetrio. (1996). The Politics of Maya Revindication . In Maya Cultural

Activism in Guatemala, Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown, Eds. Austin:

University of Texas Press, p. 19-50.

Demmert, William G., Jr.; Towner, John C. (2002). Improving Academic Performance

Among Native American Students: A Review and Analysis of the Research Literature,

Woodring College of Education, Western Washington University, Bellingham,

Washington (unpublished Rand Report).

England, Nora C. (1996). The Role of Language Standardization in Revitalization . In

Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala, Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown, Eds.

Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 178-194.

Fischer, Edward F. (1996). Induced Culture Change as a Strategy for Socioeconomic

Development: The Pan-Maya Movement in Guatemala . In Maya Cultural Activism in

Guatemala, Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown, Eds. Austin: University of

Texas Press, p. 51-73.

Fischer, Edward F.; Brown, R. McKenna. (1996). Introduction.

In Maya Cultural

Activism in Guatemala, Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown, Eds. Austin:

University of Texas Press, p. 1-18.

Heckt, M. (1999). Mayan Education in Guatemala: A Pedagogical Model and its

Political Context . International Review of Education, 45 (3/4): 321-337.

Johnson, J. (2006). Field notes from Sumpango, Guatemala. Interviews and notes.

Manu’atu, Linita; Kepa, Mere. (2001). A Critical Theory to Teaching English to

Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL): The promising focus for indigenous perspectives.

Paper presented at the PacSLRF Conference, University of Hawaii, Manoa.

Otzoy, Irma. (1996). Maya Clothing and Identity . In Maya Cultural Activism in

Guatemala, Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown, Eds. Austin: University of

Texas Press, p. 141-155.

Raxche’ (Demetrio Rodríguez Guaján) (1996).

Maya Culture and the Politics of

Development.

In Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala, Edward F. Fischer and R.

McKenna Brown, Eds. Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 74-88.

Warren, Kay B. (1996). Reading History as Resistance: Maya Public Intellectuals in

Guatemala. In Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala, Edward F. Fischer and R.

McKenna Brown, Eds. Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 89-106.