Women_s Organizing

Karin Huebner

Women’s Organizing

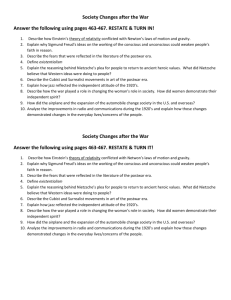

“The history of women’s organizations in the 20 th century is characterized by sharp breaks in continuity, with cultural and generational breaks occurring in the 1920s and the

1950s.” Do you agree or disagree. Discuss with reference to at least six texts from your reading.

Nancy Dye states in the introduction of her anthology on Progressive women and reform, Gender, Class, Race and Reform in the Progressive Era, “The involvement of women in progressive reform marks the high-water point of women’s engagement in

American politics.” Cott writes in The Grounding of Modern Feminism (1987) that women’s participation in volunteer organizations was never higher than in the postsuffrage 1920s. These two statements suggest continuity between the first two decades of the 20 th century and the post-suffrage 20s. Nonetheless, an examination of the political climate, as well as the cultural transformations from the1910s to the eve of the

Depression, suggests this era’s history of women’s organizations was arguably complicated by both generational and cultural challenges and changes. The 1950s are marked as well with disjunction and fluidity, in terms of cultural and political shifts, all of which impacted and informed women’s organizing and political action over the course of the decade and into the1960s. Traditional historical interpretations of both the 1920s and 1950s have viewed women’s organizational arenas as characterized by disjuncture, with women’s political activism impacted as a result of major world historical events and conservative shifts in the U.S. political, economic, and cultural spheres. I would argue that this interpretation still holds and agree that these historical factors had transformative impact on women’s organizations during the 20s and 50s. Nonetheless, historical

1

Karin Huebner revisions and new histories of 20 th century women’s organizational history argue convincingly that women’s political activism flourished and expanded during these decades amidst monumental changes in global, political, economic, and cultural climates.

For this essay, I will examine and address three cultural fronts -- the sexual, political, and popular during the 1920s and 1950s -- to argue the case for a nuanced history defined by continuity and discontinuity, thus complicating the history of women’s organizations during the 20 th century.

1920s

The history of women’s organizations during the 1920s traces its roots from the myriad of powerful women’s volunteer associations that actively participated (with great success) in political activism, labor agitation, and social reform from the 1890s to the achievement of suffrage. Nancy Cott’s The Grounding of Modern Feminism focuses on the nascent formation of feminism in the United States during the first three decades of the 20 th century and provides an exhaustive account of the multifarious women’s organizations, which she argues produced the ideological foundations of modern feminism. Cott emphasizes the disparate political agendas underpinning these associations during the first two decades of the twentieth century, but maintains that they nonetheless banded together under the single-issue -- woman suffrage.

Most of the women’s volunteer organizations involved in the suffrage movement were formed during the first decade of the progressive movement, the 1890s, and in large degree, these women defined the movement. Historians of women’s organizations agree that the ideologies of “true womanhood,” separate spheres, woman consciousness, and

2

Karin Huebner female moral superiority espoused by early women’s historians Welter, Smith-

Rosenberg, and Cott respectively, informed the women’s organizational framework, aims and agendas, and even their strategic methods for action. The “ideal” woman, who earlier was bound to the domestic sphere, was now the “new woman” who expanded that sphere into the public domain through social welfare reform organizations, nonetheless, still under the prescriptions of 19 th c. womanhood that was defined through serving others, particularly women and children, cleaning the “municipal house,” and effecting change in the corrupt political and capitalist arenas through their strategically persuasive demands for justice.

Histories on settlement house organizations, described in Kish-Sklar’s seminal work on Jane Addams and Hull House, the WCTU, founded in 1869 and politically flourishing during the progressive era on a national scale, and the moral reformers and missionary women described by Peggy Pascoe in Relations of Rescue , are representative histories of organized women operating under the “true womanhood” paradigm of the 19 th century.

And though the ideal woman was a white construction, women of color also appropriated the ideal womanhood paradigm to buttress their own moral authority and power.

Schechter in her work on Ida B. Wells, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, shows that Ida B. Wells during the 1890s used the ideal as her justification for arguing for reform.

Many of the female leaders in these women’s organizations believed that official entry into mainstream politics through gaining the vote was the next step to achieve greater reform and together they agitated for suffrage. Cott, in Grounding , details the coalescing of a number of women’s volunteer associations under suffrage who had historically

3

Karin Huebner disparate agendas for reform. The Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) formed during the 1890s to improve working-class women’s working conditions in factories and service jobs and agitated for special legislation for women. The Consumer’s League, headed by Florence Kelly, a Hull House resident, built alliances between middle-class women consumers and working-class women producers, that through increased awareness of the harmful working conditions endured by working-class women, middleclass women through persuasive politics and boycotts influenced employers and major industries to improve both working conditions and wages of women workers.

Karen Blair in Clubwoman as Feminist (1984), and Ruggles-Gere in Intimate

Relations (1998), offer revisions to the history of women’s clubs, suggesting that these conservative organizations were, in fact, actively involved in the fight for suffrage, albeit latecomers to the cause, officially backing the National American Woman Suffrage

Association (NAWSA) in 1914. Though these conservative women’s clubs promoted the assimilation of immigrants and promulgated middle-class values as the social standard upon non-bourgeois women targeted for reform, women’s clubs proliferated across the country, involving women in numerous forms of social activism. In 1892, a national body formed, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC). Katherine Kish-Sklar in

“Two Political Cultures in the Progressive Era: The National Consumers’ League and the American Association for Labor Legislation,” in U.S. History as Women’s History

( 1995 ), argues that Florence Kelly of the NCL saw advantages in allying with both the

GFWC and the WTUL as early as 1900. Throughout the first two decades of the 20 th century, the NCL formed an alliance with the WTUL and the GFWC, and NCL leaders often presented addresses at GFWC national and regional conventions across the nation

4

Karin Huebner concerning the struggles of working-class women. Ruggels-Gere expands on Blair’s earlier work, covering Black women’s clubs, organized nationally under the National

Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACW) to combat their triple-front discrimination – economic, gender, and racial. Central in the NACW’s efforts was also to bring an end to the lynching of black men.

All of these women’s organizations and reform groups, despite their disparate ideological underpinnings and their class and racial differences, together supported suffrage as a case for expediency, to further their efforts for reform. In the early 1890s, the NAWSA was formed and over the course of the next three decades, nearly all of the various women’s organizations supported the NAWSA’s single agenda -- that women are both equal to and different from men and deserve full political participation through enfranchisement.

In Grounding, Cott identifies another argument for woman suffrage among the women’s organizations, and that was as a case for justice.

A second suffrage organization, the National Women’s Party (NWP), rival to the NAWSA and more radicalized, formed in 1914. NWP leader Alice Paul, radicalized in London through her involvement with militant British suffragettes, employed aggressive labor union agitation tactics as an alternative strategy to the more “predictable decorousness” of the NAWSA.

Paul emphasized her commitment to the idea of equality between men and women on every level, economic and political in particular. By 1919, Paul formulated the NWP platform to agitate for the passage of an equal rights amendment, which would guarantee women’s equal treatment with men in the economic and political arenas. The ERA was ideologically at odds with the women’s labor organizations and other women’s groups

5

Karin Huebner that supported and achieved special legislation for women in the workplace, such as, maximum work hours, and minimum wage. The WTUL, Consumer League, and

Women’s Bureau viewed the NWP’s agenda as dangerous for women and counterproductive to the gains they had made in Washington on behalf of women. The NWP saw special legislation as a means of keeping working-class women marginalized and oppressed in the economic realm.

Dramatic shifts in women’s position in American society, which began significantly during the 1890s, were the impetus to women’s reform activism. Sharp increases in single women’s work outside the home, the rise of the new (educated, professional) woman, and the increasing number of working-class women laborers gave new force to the demand for political representation. By the 1910s, Cott argues, that the “gathering momentum for change in women’s lives displayed itself most vividly in the labor movement and the suffrage movement, themselves reciprocally influential.” (See also

Banner, WMA 2004; and K. Kish Sklar, “Two Political Cultures” ). The coalescing of labor and suffrage showed up particularly strong in the figure of Harriet Stanton Blatch, daughter of the great woman’s rights activist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. A member of the

WTUL at the turn of the century, Blatch recognized that economics were intricately wedded to women’s rights and woman suffrage was an inevitable and justified beneficiary of a new emerging female economic identity. Blatch, in 1907, formed a new suffrage organization, which combined labor with suffrage, the Equality League of Self-

Supporting Women.

Blatch’s socialist politics aligned with a radical organization of elite, feminist women who in 1914 formed the Heterodoxy Club. This eclectic group of predominately elite,

6

Karin Huebner white women identified individual self-fulfillment (sexual, personal, and economic) as a legitimate political goal. Kathy Peiss argues in her article, “We Were a Little Band of

Willful Women:” The Heterodoxy Club of Greenwich Village,” Passion and Power,

1989, that the 1960s feminist mantra, “politics is personal,” had its beginning in the

1910s among these predominately socialist, self-identified feminists. Deeply influence by Ellis and Freud and their new sexual theories on female sexuality and heterosexual companionship, Heterodoxy women embraced a female sexual ideology that espoused women’s entitlement to sexual fulfillment and freedom. Virtually all of the Heterodoxy

Club women were deeply active in organized women’s movements, suffrage, labor, and socialist, throughout the 1910s and into the 1920s.

The changes in female identity in terms of sexual, economic and political stature was reflected and tied into this new sexual liberation espoused by the Heterodoxy women. A new iconic, sexualized female image, personified by Theda Bera in the 1915 film The

Vamp , suggests the emergence in the mid-teens of a new woman whose identity was independent from motherhood and wifehood. (See Banner, WMA and American Beauty) .

In the political climate of the 1910s with women pushing for increased economic and political rights, this new sexualized ideal took hold, supplanting the sexually benign

Gibson Girl of the turn-of-the-century. This new iconic female figure, embraced by, and in many ways embodied in, the members of the Heterodoxy club, transplanted the sexually benign Gibson Girl through her free, expressive sexuality, her selfdetermination, and her power over men. The radical feminists of the Heterodoxy club embraced this new sexualized figure (and apparently, according to Cott, Theda Bera embraced the feminism of the Heterodoxy club, identifying herself as a “feministe”). By

7

Karin Huebner the late 1910s, the new sexualized woman was identified with the liberated women who demanded and won suffrage, who continued to agitate for labor reform and workingwomen’s empowerment, and who fought for social reforms.

The Vamp was a political figure in many ways, challenging and determining the new relationship women were constructing with men and society. By the early postwar era, amidst dramatic changes in the U.S. politically, culturally, and economically, another female image emerged -- the flapper -- and the changes were in many ways imprinted on her body.

The cosmetic industry provides an important arena to examine cultural changes in the

1920s in that it reflects a burgeoning culture of consumerism and is an example of an industrial complex that specifically targeted women. According to Kathy Peiss in

“Making Faces: The Cosmetics Industry and the Cultural Construction of Gender, 1890-

1930” in Unequal Sisters, advertising campaigns projected women’s political liberation and independence through their consumption of beauty products. Individual selfexpression through the use of makeup was in concert with the new ideas of female individualism of the 20s embodied in the flapper. While Peiss criticism of the cosmetic industry is justifiably harsh, seeing it as calculating and exploitive of women, she complicates the history, emphasizing women’s agency in their consumption of cosmetic products. “Women linked cosmetic use to an emergent notion of their own modernity, which included wage-work, athleticism, leisure, free sexual expressiveness, and greater individual consumption.” The female ideal of collective work manifest in the women’s organizations of the 1910s was by the 1920s augmented by a new political identity emphasizing woman’s individuality and a new social relationship shifting from female centered lives to heterosexual companionship. These changes found expression in an

8

Karin Huebner increasingly hedonistic culture where a new generation of women coming of age in the

1920s rejected the sexually repressive Victorianism of their mothers and grandmothers.

In addition, the conservative administration of the 1920s took a pro-business stance that emphasized consumption as patriotic and women were the primary targets. Along with cosmetics, new household industry products emerged on the market and women were encouraged to express their newly gained liberties and American patriotism through purchasing these new products. It has been argued that this new generation of women coming of age during the 1920s, which focused on leisure, sport, and material consumption, ideologically drifted away from female cooperative social reform that dominated the first two decades of the 20 th century.

The traditional history of this new 20s woman saw her shirk the moral responsibilities of womanhood that served to inspire the previous generation to social reform and political activism. “Social definitions of womanhood were strongly contested from the late nineteenth century onward,” writes Peiss. “The ideal of the “New Woman” represented a departure from concepts of female identity constituted solely in domestic pursuits, sexual purity, and moral motherhood. But this new ideal was an unstable one.

For some, the New Woman was a mannish, political, and professional woman who had entered the public sphere on her own terms. For others, the New Woman was a sensual, free-spirited girl…in the 1920s, the flapper.” The flapper, argues Peiss, was a complicated figure – she was at once a wage earner, independent, and sexually available to men; she was also a romantic, seeking her ultimate fulfillment in marriage. The cosmetic industry helped reshape the politically and sexually liberated woman of the

9

Karin Huebner

1910s into a new gender construction; still liberated enough make money to purchase cosmetic products, but less threatening to men, remaining sexually available to them.

Christina Simmons in “Modern Sexuality and the Myth of Victorian Repression” (see

Passion and Power ) expounds on the flapper, seeing this new female image as a male construction. Simmons argues that the “new discourse” on the Victorian myth was really a cultural adjustment of male power to women’s departure from Victorian order, associating women’s sexual liberation with their rise in political power. “The new sexual discourse (on Victorian repression) was an attack on women’s increased power.” The flapper was the central female figure in this discourse. The early 20 th century rise of a leisure culture fostered a heterosexual (and homosexual) culture to develop with new forms of amusement: dance halls, movie theatres, and nightclubs. All of these contributed to greater sexual laxity between men and women. Nonetheless, Simmons argues that with the increases in female political and economic independence and power, combined with increased control over reproduction, men had to reassert their authority within the undeniably changed gender framework. Simmons identifies the free-loving, youthful, feminized, apolitical flapper as the new, non-threatening female figure that men could embrace. I do not hold Simmons’ interpretation of the flapper, but align closer with Peiss and Banner’s interpretations. These historians see the flapper as complicated, but maintain the dominant message she expresses is female empowerment. Simmons’ interpretation views the flapper as a male construction and as a figure backlash. The flapper image may have complicated nuances, which suggest a conservative turn in the

20s in the female ideal. Nevertheless, the endurance of the flapper image as a symbol of both liberation and exploitation is evident even into the era of Second Wave Feminism in

10

Karin Huebner the 1960s and 70s. The first professional women’s sports tour sponsor, the major cigarette company William Morris, used as its advertising campaign an image of a smoking flapper coupled with the slogan, “We’ve Come A Long Way Baby,” to emphasize and celebrate the connection between the liberated woman of the 20s with the liberated women of the 1970s. The flapper image remains an enigma and deserves further study.

Due to the horrors of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, a rising conservativism arose in the postwar era. In response to the war, a number of women’s organizations emerged both in support of the war and military preparedness, such as the

Daughter’s of the American Revolution (DAR), and in opposition to military armament and action, such as the women’s peace organizations. “International peace” writes Cott,

“was, arguably, the major item of concern among organized women in the 1920s.” The

Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom (WILPF), the Women’s Peace

Union (WPU), the Women’s Committee for World Disarmament (WCWD), and the

National Council for the Prevention of War (NCPW) were organized by women who viewed the horrors of the war rooted in male aggressiveness and believed that the nation and world needed women involvement in politics and international affairs to quell masculine aggression. The major women’s organizations, the LWV, AAUW, WCTU,

NFBPW, and the PTA, joined the peace movement and put world peace as the primary focus on their agendas. Alice Paul’s rival NWP joined the cause for peace as well, and it appeared that women’s organizations again had a single issue around which to rally. In

1925, Catt formed an umbrella peace organization, the National Conference on the Cause and Cure for War (NCCCW), through which the leaders of the women’s organizations

11

Karin Huebner came together as an effective, peace-lobbying bloc. By 1930, the membership numbered over five million women.

The Bolshevik revolution and the patriotic post-war fervor in the United States gave rise to an aggressive conservative assault on radical organizations that espoused socialist and communist politics, and groups and individuals opposed to war. An anticommunist/socialist, red-baiting climate emerged in the early 20s and women’s peace organizations were increasingly attacked as un-patriotic, subversive, and dangerous.

Pacifism was associated with socialism and as a result, in 1924, the infamous “Spider-

Web Chart was issued which named virtually every women’s organization and numerous women leaders associated with peace and disarmament as linked to the international spread and threat of socialism. Anti-feminist and anti-social welfare reform sentiment was also reflected in the attack. Links were drawn between welfare reform legislation such as the WJCC’s Sheppard-Towner Act and sex-based labor legislation lobbied by the

NCL and WTUL. Even Jane Addams and her social welfare programs and agitation were attacked as a driven by socialist ideology and a threat to national security. The political and cultural conservative turns and their attendant repressive tactics, functioned to differentiate between radical socialism and progressive socialism, which had coexisted among the various women’s organizations prior to gaining the vote. NWP’s militant tactics were increasingly viewed akin to the worldwide socialist movement (although

Paul and the NWP took a neutral stand on socialism) and this created an even greater chasm between the self-identified “bourgeois, non-radical” NAWSA.

“In the Republican-dominated 1920s,” writes Cott, “women elected or appointed by the ruling party often showed more loyalty to it than to women as a group. “Women’s

12

Karin Huebner

Bloc” politics, which had dominated the first two decades of the 20 th century, was increasingly challenged by a new political strategy in the post-suffrage 20s -- women’s increased involvement in partisan politics. Two contesting issues emerged in this new political climate for women, and women grappled with which strategy would best advance women’s political power: traditional voluntarist (indirect mode, lobbying, pressure group, “women’s bloc” politics) or integration into men’s traditional partypolitics framework (direct mode, candidacies, and partisan endorsement politics). Cott argues that both options had drawbacks. The voluntarist mode perpetuated the “separate spheres” gendered structure that women fought to overcome through suffrage. The integration mode risked the status quo in politics would remain with women and their concerns effectively marginalized within the male-controlled political parties. “Women had more past experience in the voluntarist mode, and it was known to be a way to gather political momentum; on the other hand, the gain of suffrage had promised that women would be able to break free from that mold.” (Cott). A collection of essays on women’s partisan politics, We Have Come To Stay: American Women and Political Parties, 1880-

1960, (Melanie Gustafson, Kristie Miller, and Elisabeth Israels Perry, eds., 1999) details the tension between women’s use of non-partisan, or “women’s bloc” strategy, which most women’s organizations employed, and partisan politics, which ideally created gender equity in the political machine historically dominated by men. Women were involved in partisan politics during the Progressive Party campaign in 1912, but this was due in large part to the Progressive Party’s whole-hearted support of women’s reform and suffrage agendas. Kathryn Anderson’s piece, “Evolution of a Partisan: Emily Newell

Blair and the Democratic Party, 1920-1932,” focuses on Blair’s advocacy for women’s

13

Karin Huebner partisan involvement to her eventual acknowledgment by the end of the 20s that dropping the sex line was a mistake for feminism. Partisan politics, Blair came to realize, meant men could retain their power without acknowledging women. Blair, co-founder of the

Women’s National Democratic Club in 1923, initially believed in partisan politics over women’s bloc politics. In the immediate post-suffrage era, Blair argued that organized women had limited political power; she viewed clubwomen as disengaged from political issues and even the LWV was not focused on organizing women as voters. What emerged in the post-suffrage 1920s, then, was a division and “tension between dropping the sex line and creating a space for women (separate from their gender identity) in politics.” To gain true equality, according to Blair and other women leaders such as Catt and Anna Ickes, women had to enter the traditional partisan politics of men and gain election to office and political appointments to committees as individuals, not as women.

By the end of the decade, however, Blair and other partisan advocates discouragingly acknowledged that partisan women had not found an equal place within the political parties.

1950s (because of time constraints, this section is in truncated format)

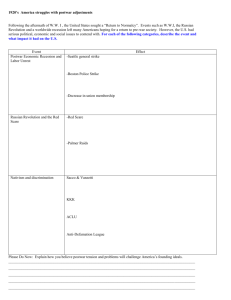

I. Argument: the history of women’s organizations in the 1950s is characterized by continuity and discontinuity similar in pattern to the 1920s. World events, such as the

Depression, WWII, the Cold War, the sharp cultural turn toward conservativism, and the redbaiting of McCarthyism provide sharp historical breaks, which significantly impacted the women’s organizations of the era. McCarthyism and the Red Scare had devastating effect on many women’s organizations; particularly those associated with the left, such as, women’s peace organizations, as well as, lesbians and abortionists. Nonetheless, women’s organizational activity during the postwar era, in large part, shows greater signs of continuity than discontinuity. Labor women’s history, women’s peace movements, civil rights agitation, and conservative turns in politics and culture are examined to support a thesis of predominant continuity in the history of women’s organizations.

II. Introduction: begins with historiographical overview of history of women in the 50s.

Then examines revisions on early interpretations or focuses of the postwar era. Starting

14

Karin Huebner with Betty Friedan’s 1963 Feminine Mystique , I will argue how her view of the 50s as a retreat to domesticity, suburbanism, the “problem that had no name” and her emphasis on the discontented white, middle-class suburban house-wife, provided the historical interpretive paradigm for postwar women’s history for nearly three decades. As late as

1988, amidst a burgeoning history on ethnic, race, and labor women histories, Elaine

Tyler May’s Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era reflects the stubbornness of Friedan’s interpretative model for the history of women in the 1950s.

May’s work centers on the instability of the Cold War era and how the idealized domestic family served to contain internal threats and threats abroad: communism, nuclear holocaust, and subversive cultural developments (secularism, materialism, homosexuality). While I hold to much of Friedan and May’s interpretation of the repressive power the postwar domestic ideal imposed upon middle-class white suburban housewives, their homogenization of women has obscured the history of postwar women of diversity: for example, ethnic and African American women’s postwar history, working-class women’s history, women’s civil rights activism, women in the peace movements, and lesbian history are not part of the Friedan/May postwar milieu.

Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945-1960.

(Joanne

Meyerowitz, ed., (1994) is a collection of fifteen revisionist essays reflecting the diversity in women’s history in the postwar era. In the introduction, Meyerowitz argues that the old model “flattens” the postwar history of women, obscuring the racial, ethnic, class, (and I would add ideological) complexities that existed, and it focuses on an era that women’s historians have paid less attention to than either before or after the postwar era. Most of the essays in this collection identify historical continuities between women organizations during the wartime and postwar eras.

Part I, of IV: five articles dedicated to women’s labor history in postwar era. Cobble’s article, “Recapturing Working-Class Feminism: Union Women in the Postwar

Era,” emphasizes the critical part union women had in articulating a new kind of feminism in the fifties. Arguing for continuity in women’s organizing, Cobble states that women in the 50s did not retreat from activism, on the contrary, working-class feminism flourished in the decade. Cobble supports the notion that women were integral actors in militant labor strike in the postwar era. A number of strikes were particularly women’s strikes.

The telephone strike in 1947 was the largest walkout of women workers in U.S. history. Retail and food-service strikes at the end of the 40s and their burgeoning union membership empowered women unionist to formulate specific female agendas reminiscent of special legislation reforms of the 1910s and 20s -- comparative wage, maternity leave, and day care to name a few. By the time of her 2004 book she coined the phrase, labor feminism to describe these women’s labor movements and labor feminists to describe the women leaders and strikers.

Susan Lynn’s article, “Gender and Progressive Politics: A Bridge to Social

Activism,” focuses on the postwar progressive politics movements and their agitation for the expansion of welfare state, labor reform, and particularly racial justice. Civil rights activism gained momentum in postwar era and a progressive coalition of middle-class women’s organizations worked together, employing strategies and tactics that relied on the female ethic similar to early 20 th century “maternal housekeeping” progressive women. The AAUW, the LWV, the NCNW, the WILPF, and the YWCA were among the most important women’s organizations involved in postwar progressive reform, the

15

Karin Huebner difference between the early 20 th century movement and this one was its focus on racial justice. Lynn’s study focuses on the YWCA and the American Friends Service

Committee (mixed-sex organization) as useful models for women’s activism in the years before and after the war, making a convincing argument for continuity in women’s organizational activity. The YWCA was one of the first women’s organizations that questioned its segregation policies. As early as 1920, due to black YWCA women’s agitation, the national YWCA began to move from a biracial organization to an interracial one. In 1934, the YWCA adopted an integration policy at all of its national conventions. By 1946, with increased demands of both black and white members advocating for integration, the YWCA adopted an “Interracial Charter.” Civil rights measures and agitation became the major focuses in the YWCA’s agenda from 1946 on -- antilynching legislation, abolition of the poll tax, all major civil rights bill before

Congress, and anti-racist education programs to young women and girls were all a part of the YWCA’s efforts during the postwar era.

The Second World War delivered a devastating blow to the women’s peace movement in the United States, according to Harriet Hyman Alonso in “Mayhem and Moderation:

Women’s Peace Activists During the McCarthy Era” in Not June Cleaver.

In the postwar, anti-communist climate, women’s peace organizations such as the newly formed

Council of American Women (CAW) and the American Women of Peace (AWP), and the long establish WILPF increasingly came under attack by McCarthy and his redbaiting tactics. McCarthyism and HUAC targeted citizens who opposed the war, the military build-up of the U.S., atomic weapons development, and advocated international coalitions to sustain peace, as communist traitors and subversives. The U.S. government openly attacked left-leaning women’s organizations such as CAW and AWP, particularly through the 1950 McCarren Act, which mandated that CAW leaders register as “foreign agents.” Both organizations disbanded within three years of organizing. The WILPF suffered dissention under McCarthyism, as members’ suspicions rose internally, and the redbaiting of fellow members ensued. Hyman’s essay focuses on the WILPF and their strategies to sustain their organization in the midst of the repressive postwar era. The

WILPF distanced itself from communism, at the same time supporting free speech and the right to dissent. The survival of the WILPF, argues Alonso, depended on its eventual adoption of anti-communist rhetoric and its attempts to appear moderate, linking its peace ideology to traditional female concerns. The WILPF faltered during the ultraconservative McCarthy era, but it did survive.

Daniel Horowitz’s revisionist historical biographies on Betty Friedan, “Rethinking Betty

Friedan and The Feminine Mystique : Labor Union Radicalism and Feminism in Cold War

America,” in Unequal Sisters and his subsequent book, Betty Friedan and the Making of

The Feminine Mystique: The American Left, the Cold War, and Modern Feminism (1998) argue that Friedan was not enlightened to her feminist consciousness through her discontent as a suburban housewife. Rather, in his revision of Friedan’s own autobiographical account in The Feminine Mystique , Horowitz’s interpretation fits

Friedan more into the Cobble’s schema from her recent publication, The Other Women’s

Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights, (2004) -- that of the middle-class agitator in labor feminist movements of the 1940s and 50s. Horowitz emphasizes the continuity between Friedan’s union labor work during the 1940s and 50s and the

16

Karin Huebner feminism she prompted in the 60s. Horowitz highlights the damage done to progressive social movements of the 40s and 50s by McCarthyism, and postulates that this may have driven Friedan underground or at least by the early 60s a conservative shift politically from her radical postwar days. What Horowitz illuminates in his revision on Friedan, and what is pertinent for this essay, is the continuity of Friedan’s political-left radicalism, evident in her tenure as a labor journalist for the EU during the postwar years, in spite of repressive McCarthy-red-baiting era of the early 50s. “Recognition of continuity in

Friedan’s life,” writes Horowitz, “gives added weight to the picture that is emerging of ways in which WWII, unions, and those influenced by American radicalism of the 1940s provided some of the seeds of protest movements of the 1960s.”

Cobble’s recent work is a synthesis on 20 th century labor women activism, inclusive of ethnic women and African American women labor activists, identifying these women as labor feminists (I dig her invention of this term), true foremothers to later feminists in the

60s and 70s. Cobble shatters the premise that feminism in the U.S. was an elitist movement, appealing to white, middle and upper-class women, but not to working-class women or women of color. She traces the history of labor feminism from the workingclass movements of the 1910s, such as the Equality League headed by Harriot Stanton

Blatch, Florence Kelly and the Consumer’s League, and the WTUL under the leadership of Mary Anderson, to the 1930s and 40s labor feminist agitation, and ultimately to current female labor protests. The 1930s and 40s labor feminists lobbied for female issue reforms, such as maternity benefits, day care, and comparable wages, reflecting the special legislation reforms agitated earlier in the century by the WTUL, Equality League,

Consumer League, and the Women’s Bureau.

Cobble presents evidence that post-WWII white, ethnic, and African American labor feminists ideologically conflated class concerns with racial discrimination and civil rights. Female organization with the United Auto Workers (UAW) is a case in point.

Cobble centers on Caroline Davis, head of the Women’s Bureau in the UAW from 1948 to 1973. Leader of a strong contingent of women labor unionists, a significant number of whom were women of color, Davis saw workplace discrimination on two fronts -- gender and race – and believe that battling both congruently was “good unionism.”

Cobble also emphasizes generational continuity between the early century female labor union leadership with the 30s and 40s leaders, and this second generations’ mentorship to the next generation of labor feminists. a. Ethnic and African American Labor:

1.

Elizabeth Faue, Community of Suffering and Struggle: Women, Men, and the

Labor Movement in Minneapolis, 1915-1945, (1991); and

2.

Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-

1939;

3.

Vicki Ruiz, Cannery Women, Cannery Lives: Mexican Women, Unionization, and the California Food Processing Industry, 1930-1950, (1987; late add to list).

4.

Vicki Ruiz, From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in the 20 th

(1998).

Century ,

17

Karin Huebner

5.

Douglas Flamming, Bound For Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow Era,

2005. (Not on list, but focuses strongly on Black women’s organizing in labor, reform, and civil rights. I would definitely put parts of this book on a syllabus).

6.

George Sanchez, Becoming Mexican America . (Also not on list, but much of

Sanchez’s work emphasizes women’s role in social and labor activism. Would assign parts of book in class syllabus).

The first four books coalesce well for understanding of labor history in 20 th century

America. Cohen’s work marginalizes women laborers, so is less helpful, but Making a

New Deal provides a useful historical framework of ethnic, working-class communities and the historical shift among the ethnic citizenry from ethnic identity which dominated in the 1920s to a class identity in the 30s. Her argument rests primarily on the power of mass culture consumption as a unifying factor between disparate ethnic groups that had difficulty organizing in the 20s, leading to failures in union agitation. Shies away from calling it Americanization, but essentially, it appears this is what she means. Also sees the welfare capitalism of the 20s as precursor to higher expectations among workers of the U.S. Government during the New Deal. Disappointments led to organization.

Elizabeth Faue is a gendered study of labor activism and fills in the gaps left by Cohen.

Faue sees women severely marginalized in the national union bureaucracies. Helps understand women’s militant and persistent labor activism in Depression era. Genderizes labor, but doesn’t racialize enough. Probably not her fault, her subjects are mostly working-class whites.

In both of Ruiz’s works, Mexican women are center actors; both part of New Social

History rubric. Out From the Shadows is more general history of Mexican and Mexican

American women in the U.S. but does focus in various places in the book on Latina labor agitation and unionizing. Cannery Women, Cannery Lives traces the historical experiences of Mexican women in the canning and packing industry in Depression to postwar eras. The United Canning, Agriculture, Packing Allied Workers Association

(UCAPAWA) – over 50% members were women, most ethnically Mexican. Women were very active in union, providing strong leadership and militant tactics. Luisa

Moreno, also featured in Ruiz’s Out From the Shadows , most charismatic, but represented one of many Mexican American women union leaders. Ruiz argues that women’s organizing was key to union’s successes. High point in the 30s, but HUAC and antiunion Taft-Hartley Act brought about witch hunts which drained the union of finances and its leaders. In fact, Luisa Moreno was deported.

Conclusion

The conservative shifts in both the 1920s and 1950s, expressed in the assaults on radical feminists, women communists and socialists, labor women, female peace activists, and women reform associations during both Red Scare eras arguably influenced

18

Karin Huebner many women’s organizations to retreat from the more radical agendas and tactics.

Nonetheless, I agree with the current consensus among historians -- Cott, Banner,

Gustafson, Meyerowitz, Cobble and Peiss -- that the history of women’s organizations in the 1920s and 1950s argue more convincingly for continuity than discontinuity. Cobble’s work particularly emphasizes continuity within women’s organizations in the labor activism of ethnic and African American women laborers from the 1910s through the

50s. Do changes in the sexual and cultural climates provide an argument for discontinuity? I would argue yes, but to a limited extent. The younger generation of women coming of age during the 20s were more independent minded and sexually liberated, and practiced more self-indulgent leisure lifestyles in contrast to reform women who, under the Victorian precepts of true womanhood, structured their lives around service to others. I think it is equally arguable for both the 20s and 50s that the assault on women’s increased political power and social influence served as an impetus for women to be more stalwart, more resolute, in their efforts and activism for change. I see this question still “on the floor” and continued analysis that links popular culture with political culture is welcome.

The 1924 Spider Web chart, the advent in1938 of House Un-American Activities

Committee, and McCarthyism’s attack on women’s peace and labor organizations during the early 1950s stymied many of the policies and programs pushed by women’s organizations, around which they either had to negotiate or disband. In the 1921, for example, under the leadership of Julia Lathrop Lathrop of the Childrens’ Bureau,

Congress passed the Sheppard-Towner Act. But Lathrop had to negotiate around conservative, pro-business/pro-medical association politicians, and couch her agenda as

19

Karin Huebner child welfare; nonetheless, her mother and child welfare agenda was frustrated with the governments’ decision, influenced by medical association lobbyists, to cease the program in 1927. Similarly, the WILPF in the McCarthy era retreated to more moderate positions to survive. Women did not have enough individual power after the vote although many women wanted to effect change within the male political system of partisan politics as opposed to non-partisan politics generally associated with women’s organizations. (they relied on Women’s Bloc strategies, which had worked effectively to gain suffrage and other important reforms). Non-partisan politics went ahead in the 20s, but female partisan political action proved frustrating. By the late 20s women’s political action launched a new era of women’s political engagement, with E. Roosevelt as the catalyst networking political and social reform female activists, most of whom, according to

Banner in WMA, were the same women active during the first three decades of the 20 th century. ER gathered together women’s organizations, such as, the League of Women

Voters, the Consumer’s League, and the WTUL, and called a White House Conference on the Emergency Needs of Women. (See Banner, WMA) . This conference prompted intense female political activity over the course of the New Deal. ER lobbied her husband to include and appoint women leaders from these organizations as leaders in his administration and New Deal programs. According to Banner, women from organizations such as the Consumer’s League and the WTUL were appointed to every

New Deal agency concerned with social welfare. With E. Roosevelt’s influence, FDR appointed Florence Allen as the first female judge on the Circuit Court of Appeals, and selected Frances Perkins, a leader in the from the NY Consumer’s League as Secretary of

Labor. Banner argues that the work and experience these women gained in the women’s

20

Karin Huebner organizations during the first three decades of the 20 th century produced the women leaders in the Roosevelt administration and the national political scene, providing additional evidence of generational continuity in 20 th century women’s organizing.

In spite of the cultural changes in the 1920s and the new liberalized female generation coming of age, the most convincing theories argue for continuity among the women’s organizations. Cott and other historians of women’s organization and politics in the 20 th century, argue that too much emphasis has been placed on the Nineteenth Amendment as the watershed moment, obscuring continuities in women’s political behavior before and after suffrage. Banner, Cott and others point to the suffrage leaders, many of whom continued their voluntarist political activism in the 20s, and developed expertise in operations of government, proceeded onto state and national positions as part of Eleanor

Roosevelt’s Women’s Network during the New Deal era. Cott, Gustafson and others see striking continuities in women’s voluntarist politics throughout the 20 th century – the prevalence of the voluntarist mode of political action; the use of persuasive, lobby tactics to effect political change; and the types of agendas pursued which were persistently centered on what was perceived as “women’s interests” – argue most convincingly for continuity in the 20s and 50s.

World events, such as, World War I, the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, the

Bolshevik revolution and its attendant “red scare” era, the advent of the Depression,

World War II, the postwar anti-communist paranoia and the Cold War, McCarthyism and the second “red scare,” function as historical breaks, or discontinuities, and can be used to organize the 20 th century and help illuminate the history of women’s organizations within this framework. The critical importance in identifying breaks in continuity

21

Karin Huebner through these historical events is that it helps identify patterns of backlash against women’s advances in American society, whether in their sexual liberation, increased control over their bodies, or political empowerment. Patterns of backlash are evident in the 1890s, 1920s, 1950s, and 1980s, and locating the historical moments that effected attacks on women’s organizations are arguably the most necessary historical breaks for the study of 20 th century America.

22

Karin Huebner

Cott; too great focus on the achievement of the Nineteenth Amendment can obscure surrounding continuities in women’s political behavior and the situation of that behavior in broader political and social context. (85)

Cott: “Striking continuities tend to be overlooked if 1920 is supposed to be the great divide and only electoral politics its sequel. The most important is women’s favoring the pursuit of politics through voluntary associations over the electoral arena.” (85) “In the prevalence of the voluntarist mode (stemming from women’s organizations), the use of lobbying to effect political influence, and the kinds of interests pursued (that is, health, safety, moral and welfare issues), there is much more similarity than difference in women’s political participation before and after

1920.” (85-86)

Cott: “it is highly probable that the greatest extent of associational activity in the whole history of American women took place in the era between the two world wars, after women became voters and before a great proportion of them entered the labor force.”

(97). “The suffrage campaign had brought its leaders, many of whom continued in voluntary associations, a great deal of expertise in the behind-the-scenes operations of government, and they proceeded to apply that expertise in state legislatures and on Capitol Hill.” (97). Banner in WMA, and Cott in Grounding both see the end of the 20s and early 30s as a new moment in women’s history with E. Roosevelt’s impact of bringing these women into government positions. Frances Perkins, first woman appointment to presidential cabinet – sec of the interior.

Feminist groups and social reform organization with socialist underpinnings in the

Settlement house agendas and social reform agitation, the Women’s Bureau and

Children’s Bureau organization (led by Mary Anderson and Julia Lathrop respectively), the women’s peace movements that arose in the postwar period, the

WILPF, the WPU, and the WCWD, the NCCCW were dramatically impacted by the Bolshevik revolution and the Red Scare that followed. The Spider Web chart and other red baiting tactics radically impacted the women’s organizations, according to Cott in Grounding, and Banner in WMA

Sexuality: independence as a woman, rather than a female/feminist consciousness, addressing women’s issues. Conflict

See: Judith Schwarz, Kathy Peiss, and Christina Simmons, “We Were a Little Band of Willful Women”: The Heterodoxy Club of Greenwich Village.” Pre-20s sexuality;

Christina Simmons, “Modern Sexuality and the Myth of Victorian Repression.”

Simmons argues that a revision on Victorian sexuality during the 1910s and 20s was really an act of reassertion of male power over women. With the increased presence of women in the labor force, the winning of suffrage and the consequent perceived increase in female political power, and the increased demand for sexual liberation combined with increased control over reproduction, men had to refashion female sexuality to a benign, albeit still sexually available female image, hence the construction of the flapper, an adolescent, innocent, yet sexualized, nonetheless nonthreatening figure. My only contention with Simmons’ argument is that she presupposes the flapper as a male construction. Women were ready to let loose,

23

Karin Huebner after the horrors of war, and the new leisure culture and relatively constrained hedonism. pre-20s to 20s sexual culture; Lois Banner, Intertwined Lives.

The National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the Women’s

Trade Union League (WTUL) headed by socialist and labor activist Florence Kelly, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) headed by Frances Willard until 1898, the Consumer League headed by Florence Kelly

Continuity in generational leadership and modus operandi:

Post suffrage – the LWV took a non-partisan position

The NFBPW active in the 20s

The YWCA

The WTUL in alliance with the Women’s Bureau defended sex based protective legislation, (in opposition to the Women’s Party who fought for ERA)

ABCL (American Birth Control League)

AAUW (American Association for University Women

The NACW then the NCNW headed by Mary Bethune

WILPF, WPU, NCCCW,

All of these organizations operated under the volunteerist mode, non-partisan politics, women’s issues particularly rather than partisan issue focused.

This analysis on women’s organization begs certain questions: can the 20 th century be organized into distinct historical eras to study of women’s organization, women’s political activism, labor agitation etc., as historians have done in the past? With

One of the major criticisms of Cott’s Grounding, was her emphasis on class, but marginalization of women of color in her analysis of women’s labor union organizations.

Also, the conservative turn in the construction of the ideal woman and the retreat to domesticity during the 50s arguably had implications of greater severity for women as a whole -- women of color, working-class women, as well as, white middle-class women

24