Symptoms at the end of Life

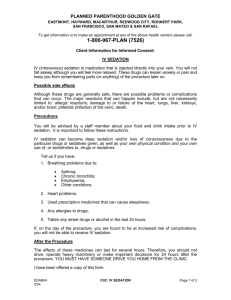

advertisement

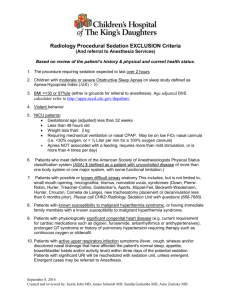

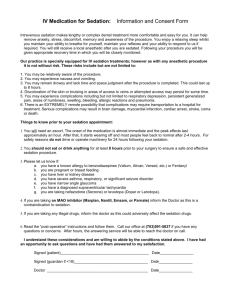

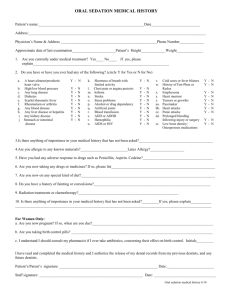

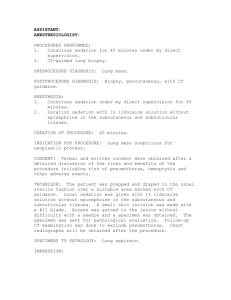

Sedation NATHAN I. CHERNY. M.B.B.S., F.R.A.C.P. Director, Cancer Pain and Palliative Medicine Dept Medical Oncology Shaare Zedek Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel Correspondence to: NATHAN I. CHERNY. M.B.B.S., F.R.A.C.P. Director, Cancer Pain and Palliative Medicine Dept Medical Oncology Shaare Zedek Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel Summary At the end of life, all patients have the right to the adequate relief of physical symptoms. There is need to ensure that appropriate infrastructural measures are addressed to enhance the likelihood that this right will be fulfilled. Symptoms at the end of life must be assessed. The adequacy of symptom relief is determined by the patient. Inadequately received symptoms in dying patients must be relieved to the patient’s satisfaction. Symptoms that are difficult to control must be evaluated by clinicians expert in symptom control at the end of life. When a symptom is refractory to normal palliative approaches, and only sedation can provide the needed relief, this should be available to patients (with appropriate infrastructural guidelines to prevent the inappropriate application of this approach) Sedation in the context of palliative medicine is the monitored use of medications intended to induce varying degrees of unconsciousness to induce a state of decreased or absent awareness (unconsciousness) in order to relieve the burden of otherwise intractable suffering. The intent is to provide adequate relief of distress (1). Sedation is controversial insofar as it diminishes capacity: capacity to interact, to function, and, in some cases to live. In the context of a field of endeavor committed to helping the ill and suffering to live better, there is a potential contradiction of purpose. Sedation for the relief of suffering touches at the most basic conflict of palliative medicine: are we doing "enough" or are we doing "too much". This issue exemplifies the tensions in achieving the duel goals of palliative care: firstly, to relieve suffering and, secondly to do so in such a manner so as to preserve the moral sensibilities of the patient the professional carers and concerned family and friends. Sedation is used in palliative care in several settings: 1 Transient controlled sedation 2 Sedation in the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life 3 Emergency sedation 4 Respite sedation 5 Sedation for psychological or existential suffering Each of these will be discussed describing the context of application, practical and ethical considerations. TRANSIENT CONTROLLED SEDATION Transient controlled sedation is routinely and uncontroversially used to manage the severe pain and anxiety associated with noxious procedures. Sedation enables patients to endure interventions that would otherwise be intolerable. The depth of sedation required is influenced by the nature of the noxious stimulus, the level of relief achieved by other concurrent approaches, and individual patient factors. When these techniques are well applied, reports of pain and suffering are infrequent. Since these patients are expected to recover, careful attention is paid to maintaining adequate ventilation, hydration, and nutrition. Occasionally transient sedation will be needed for a self limiting severe exacerbation of pain (2). In the full anticipation that this will be a reversible intervention of last resort, close monitoring of respiratory and homodynamic stability is essential. In one case report this was achieved with midazolam administered by a patient controlled analgesia device (2). SEDATION IN THE MANAGEMENT OF REFRACTORY SYMTOMS AT THE END OF LIFE (PALLIATIVE SEDATION) At the end of life the goals of care may shift and the relief of suffering may predominate over other considerations relating to functional capacity. In this setting, the designation of a symptom as "refractory", may justify the use of induced sedation, particularly since this is the only option that is capable of providing the necessary relief with certainty and speed. Various names have been applied to the issue of sedation in this setting: Terminal sedation, palliative sedation. Though no single term has achieved universal support, of these options, palliative sedation is generally preferred (3-6). Symptoms at the end of Life Among patients with advanced cancer, clinical experience suggests that optimal palliative care can effectively manage the symptoms of most cancer patients during most of the course of the disease. Although physical and psychological symptoms cannot be eliminated, but are usually relieved enough to adequately temper the suffering of the patient and family (7-12). This phase may be referred to as the ambulatory phase of advanced cancer. As the disease progresses and the end of life approaches, patients commonly suffer more physical and psychological symptoms (including pain) it often becomes more difficult to achieve adequate relief (13-16). For some patients, the degree of suffering related to these symptoms may be intolerable. Despite intensified efforts to manage such problems, some patients do not achieve adequate relief and they continue to suffer from inadequately controlled symptoms that may be termed "refractory". Refractory symptoms at the end of life The term "refractory" can be applied to symptoms that cannot be adequately controlled despite aggressive efforts to identify a tolerable therapy that does not compromise consciousness. The diagnostic criteria for the designation of a refractory symptom include that the clinician must perceive that further invasive and noninvasive interventions are either 1) incapable of providing adequate relief, 2) associated with excessive and intolerable acute or chronic morbidity, or 3) unlikely to provide relief within a tolerable time frame. The implication of this designation is that the pain will not be adequately relieved with routine measures and that sedation may be needed to attain adequate relief. Epidemiology of refractory symptoms at the end of life The prevalence of refractory pain at the end of life remains somewhat controversial (17-20). The use of sedation in the management of refractory symptoms has been evaluated in several studies over the past 10 years (19, 21-24) (Table 1). In a study of homecare patients treated by the palliative care service of the Italian National Cancer Institute, Ventafridda found that 63 of 120 terminally ill patients developed otherwise unendurable symptoms which required deep sedation for adequate relief (19). In almost half of these cases the underlying problem was severe pain. In a retrospective survey of 100 patients who died in an inpatient palliative care ward, Fainsinger et al (21) found that 16 patients required sedation for adequate symptom control prior to death, 6 for pain. An additional 2 patients who may have benefited from sedation died with severe uncontrolled pain. . Stone (23) compared two palliative care services in London, England and retrospectively looked at 115 patients. They found that 30 patients (26%) were prescribed sedatives in order to sedate them. The commoner reasons were agitated delirium, mental anguish, pain, and dyspnea. Survey data show that 5% to 35% of patients in hospice programs describe their pain as "severe" in the last week of life and that 25% describe their shortness of breath as "unbearable" (25) Sedation at the end of life as a clinical dilemma Persistent severe pain at the end of life challenges the clinician clinically, emotionally and morally and contributes to the onerous nature of clinical decision-making in this setting. It is useful to recognize both the clinical and the ethical dimensions of this dilemma. From a moral perspective, there is a major dilemma related to non-malfeasance. Clinicians want neither to subject severely distressed patients to therapies that provide inadequate relief or excessive morbidity, nor to sacrifice conscious function when viable alternatives remain unexplored. The clinical corollary of this moral dilemma is the need to distinguished a “refractory” pain state from a "the difficult situation," which could potentially respond within a tolerable time frame to non-invasive or invasive interventions and yield adequate relief and preserved consciousness without excessive adverse effects. The challenge inherent in this decision-making requires that patients with unrelieved symptoms undergo repeated evaluation prior to progressive application of routine therapies. Case conference approach to decision making Since individual clinician bias can influence decision-making (26, 27), a case conference approach is prudent when assessing a challenging case. This conference may involve involving the participation of oncologists, palliative care physicians; specialists form other fields relevant to the prevailing symptom control problem, nurses, social workers and others. The discussion attempts to clarify the remaining therapeutic options and the goals of care. Clearly, it is critical that clinicians who are expert in symptom control be involved in the patient evaluation. When local expertise is limited, telephone consultation with physicians who are expert in palliative medicine is strongly encouraged. CLINICAL PRACTICE Preconditions and guidelines In a thoughtful review, Wein (28) described a set of 9 clinical preconditions for the consideration of sedation in the management of refractory symptoms: 1. The illness must be irreversible and advanced with death imminent. 2. The symptoms need be determined to be untreatable and refractory by other means. 3. The goals of care must be clear. 4. Informed consent from the patient (direct, living will, advanced directives); or by proxy, must be obtained. 5. Corroborative consultation should be sought. 6. The staff should be involved and informed as appropriate. 7. The family should be involved as guided by the patient’s wishes and clinical condition. 8. Full documentation of clinical condition and medication. 9. Agreement must be undertaken that CPR will not be initiated. A Clinical Practice Guideline has been published in Canada (29). The purpose of the guide is to establish ethically acceptable criteria and guidelines for the use of palliative sedation as a form of treatment for intractable pain and symptoms associated with acute or chronic morbidity in the palliative care setting. The guideline defines palliative sedation and refractory symptoms states the rational for the use of sedation and sets criteria for it application. In this guideline the basic criteria for considering the use of palliative sedation include the following; 1) A terminal disease exists, 2) The patient/client suffers from a refractory symptom/s., 3) In all but the most unusual circumstances, death must be imminent (within days) and 4) A do not resuscitate order must be in effect. If the criteria are met, then a 5 step process is set in progress: 1 The attending physician shall ensure the patient is assessed by a physician expert in symptom management. 2 The attending physician, based on the recommendation and advice from a physician expert in symptom management shall consult directly with the patient and family and as appropriate with the other care providers regarding the option of palliative sedation. 3 If the option of palliative sedation is selected by the patient or ‘agent’ as identified within the Personal Directives Act, the attending physician or physician expert shall ensure the discussion by which the appropriate consent was obtained is documented on the health record. 4 Once consent is obtained for palliative sedation, the physician expert in symptom management will arrange for palliative sedation and appropriate monitoring of the patient. 5 The existing criteria and rationale used to determine the patient is a candidate for palliative sedation and the consultation process between the attending physician, palliative care consultants, patient and family will be documented on the health record. It is important to note that this guideline explicitly indicates that expertise in the area of pain or symptom management is required by the health care disciplines implementing palliative sedation. Discussing sedation with the patient and their family members If the clinician perceives that there is no treatment capable of providing adequate relief of intolerable symptoms without compromising interactional function, or that the patient would be unable to tolerate specific therapeutic interventions, refractoriness to standard approaches should be acknowledged. In this situation, the clinician should explain that, by virtue of the severity of the problem and the limitations of the available techniques, the goal of providing the needed relief without the use of drugs that may impair conscious state is probably not possible. The offer of sedation as an available therapeutic option is often received as an empathic acknowledgment of the severity of the degree of patient suffering. The enhanced patient trust in the commitment of the clinician to the relief of suffering may, in itself, influence decision-making, particularly if there are other tasks or life issues that need to be completed before a state of diminished function develops. Indeed, patients can, and often do, decline sedation, acknowledging that symptoms will be unrelieved but secure in the knowledge that if the situation becomes intolerable this decision can be rescinded. Alternatively, the patient can assert comfort as the paramount consideration and accept the initiation of sedation. With the hope and knowledge that it may be possible to achieve adequate relief without compromising interactional function, the patient who equally prioritizes comfort and function may elect to pursue only those approaches with modest morbidity, despite a relatively low or indeterminate likelihood of success. As the goals of prolonging survival and optimizing function become increasingly unachievable, priorities often shift. When comfort is the overriding goal of care, and the principal intent of any further intervention is to achieve lasting relief, there may be no tolerable time frame for exploring other therapeutic options. In this situation, interventions of low or indeterminate likelihood of success are often rejected in favor more certain approaches, even if they may involve impairment of cognitive function, or possibly foreshortened duration of survival. This situation becomes more complicated when the clinician is less certain that the available approaches will fail. Therapeutic decision-making is strongly influenced by the patient's readiness to accept the risk of morbidity and enduring discomfort until adequate relief is achieved. As always, patient evaluation of therapeutic options requires a candid disclosure of the therapeutic options, including information regarding the likelihood of benefit, the procedural morbidity, the risks of side effects, and the likely time to achieve relief. If these are acceptable to the patient, then further trials of standard therapies should be pursued. If the patient requires relief and either the procedural morbidity, the risks of adverse effects or the likely time to achieve relief are unacceptable, then refractoriness should be acknowledged and sedation should be offered. These decisions are usually made by consensus between the clinicians, the patient and the patient’s family. The process of this decision-making is predicated on an understanding of the goals of care for the individual patient. These goals can generally be grouped into three broad categories: 1) prolonging survival, 2) optimizing comfort (physical, psychological and existential) and 3) optimizing function. The processes of goal prioritization and informed decision-making require candid discussion that clarifies the prevailing clinical predicament and presents the alternative therapeutic options. Other relevant considerations, including existential, ethical, religious and familial concerns, may benefit from the participation of a religious counselor, social worker or clinical ethics specialist. With the patients’ consent, it is prudent to involve the family in these discussions. They suffer with the patient and will survive with the memories, pain and the potential for guilt at not having been effective advocates for their loved one: either because the patient died in unrelieved pain or remorseful that the patient may have been sedated when other options were not given a fair chance. If it is agreed that sedation is the most humane and appropriate way to control symptoms, it is advisable to ask the patient and family members if they have any specific goals that need to be met prior to starting sedation or if they would appreciate a chaplain/spiritual support prior to starting sedation. Discussing sedation with the ancillary staff members Involvement of ancillary staff such as social workers, primary care nurse, psychologist and other health professionals is a point that cannot be adequately emphasized. Just as cancer is a family illness, so is its management a team effort. Information about who the patient is comes from many sources; the patient and family will find support and connect with different personalities; team involvement allows support for its members, prevents burn-out and helps monitor counter transference issues (28). Consent and "DNR" status Consent to the use of sedation acknowledges the primacy of comfort as the dominant goal of care. The initiation of cardiorespiratory resuscitation (CPR) at the time of death is almost always futile in this situation (30-32), and furthermore, is inconsistent with the agreed goals of care (30, 32). Sedating pharmacotherapy for refractory symptoms at the end of life should not be initiated until a discussion about CPR has taken place with the patient, or, if appropriate, with the patient's proxy, and there is agreement that CPR will not be initiated. Drug selection The published literature describing the use of sedation in the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life is anecdotal and refers to the use of opioids, neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, barbiturates and propofol. Opioids: In the management of pain, an attempt is usually made to first escalate the opioid dose. Although some patients will benefit from this intervention, inadequate sedation, or the development of neuroexcitatory side effects, such as myoclonus or agitated delirium, often necessitate the addition of a second agent (33-35). Midazolam: In general midazolam is the most commonly used agent (22, 24, 36-42). This benzodiazepine has a relatively short half life and therefore, for the purposes of palliative sedation, generally needs to be administered by continuous infusion. The short half life also allows for rapid dose titration. A subcutaneous or intravenous line can be used. A starting dose of midazolam 1mg/hr by continuous infusion is suggested. This dose may need to be titrated rapidly to effect. In most cases, doses of between 1mg/hr - 7 mg/h are required. Some suggest using a higher dose of sedative initially in order to obtain sedation as soon as possible. Once deep sedation is induced, the dose should be lowered until the lowest effective dose to maintain sedation has been found. Reassessments of patients are required on a regular basis. Rarely, benzodiazepine drugs can cause a paradoxical agitation, and an alternative strategy is required. Barbiturates: Greene (43) reported experience in the management of refractory physical symptoms using barbiturates alone among 17 imminently dying terminally ill patients suffering from persistent physical symptoms. Amobarbital (9 cases) or thiopental (8 cases) were used and adequate symptom relief was achieved in all cases. The median survival of these patients after initiation of the infusion was 23 hours (range 2hr-4 days). Although most of the patients maintained interactional function for a time, all patients died in their sleep. This approach has been endorsed by Troug et al (44), who also described the potential utility of barbiturates for terminal agitation or terminal anguish. Methotrimeprazine: Methotrimeprazine is an antipsychotic phenothiazine which can be administered orally or parenterally (IV, SC or IM). Parenterally, it is often used to provide sedation in the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life (45, 46). In addition to its sedative properties, it is also moderately analgesic. Parenteral dosing is conventionally started 6.25mg q8 hourly (h) and q 1h prn for breakthrough agitation. If necessary, the dose may be increased to 12.5 or 25mg q8h and q1h prn for breakthrough agitation. Orthostatic hypotension is a common adverse effect and this medication is best avoided for ambulatory patients. Clorpromazine: Chlorpromazine is an antipsychotic phenothiazine which can be administered orally, parenterally (IV or IM), and rectally. It has been used to provide sedation in the setting of agitated delirium and refractory dyspnea at the end of life (47). In this published experience, the median rectal dose was 25 mg every 4-12 hr and the median IV dose was 12.5 mg every 4-12 hr (47). It is a relatively cost effective option that can be easily used in the home (48). Propofol: There published experience in the use of propofol for sedation in this setting is anecdotal (39, 4952). In the rare event that other agents have been unable to provide adequate relief its anesthetic properties may be particularly useful to provide sedation. Propofol is very similar to the short-acting barbiturates but it has a short duration of action and a very rapid onset. These characteristics make it relatively easy to titrate (50). In one report the patient was started on a loading dose of 20 mg, followed by an infusion of 5070 mg/hr (51). Drug administration The management of sedating pharmacotherapy for refractory symptoms in patients with advanced cancer demands a high level of clinical vigilance. Irrespective of the agent selected, administration initially requires dose titration to achieve adequate relief, followed subsequently by provision of ongoing therapy to ensure maintenance of effect. The depth of sedation that is required to achieve adequate relief is highly variable. In some situations, patients may require only light sedation to achieve adequate relief, in other situations, particularly at the end of life, deep sedation may be required. Regular, "around the clock" administration can be maintained by continuous infusion or intermittent bolus. The route of administration can be IV, SC or rectal. In some situations drugs can be administered via a stoma or gastrostomy. In all cases, provision for emergency bolus therapy to manage breakthrough symptoms is recommended. Patient monitoring Once adequate relief is achieved the parameters for patient monitoring and the role of further dose titration is determined by the goal of care: 1. When the goal of care is to ensure comfort until death for an imminently dying patient: In this setting the only salient parameters for ongoing observation are those pertaining to comfort. Symptoms should be assessed until death; observations of pulse blood pressure and temperature do not contribute to the goals of care and can be discontinued. Respiratory rate is monitored primarily to ensure that absence of respiratory distress and tachypnea. Since downward titration of drug doses places the patient at risk for recurrent distress, in most instances it is not recommended even as the patient approaches death. 2. If the patient wishes to be less sedated and dying is not imminent; in this context comfort, the level of sedation and routine physiological parameters such as heart rate blood pressure and oxygen saturation are monitored. In these cases, the drug should be administered by the lowest effective dose that provides adequate comfort. The depth of sedation necessary to control symptoms varies greatly. For some patients, a state of "conscious sedation," in which they retain the ability to respond to verbal stimuli, may provide adequate relief without total loss of interactive function (22, 38, 42, 43). Some authors have suggested that doses can be titrated down to reestablish lucidity after an agreed interval or for pre-planned family interactions (22, 43, 44). This, of course, is a potentially unstable situation, and the possibility that lucidity may not be promptly restored or that death may ensue as doses are again escalated should be explained to both the patient and family. Nutrition and hydration when patients are sedated Contrary to the assertions of Quill (53, 54) and Orentlicher (55) the discontinuation of hydration and nutrition are not essential elements to the administration of sedation in the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life. While there is wide consensus that invasive forms of enteral or parenteral nutrition are not essential aspects of care for patients who lose the ability to eat and drink at the end of life (56), no consensus exists regarding the withholding of hydration and available data do not support the assertion that it is "typical" (55) or essential the approach of “terminal sedation” (53, 57). Opinions and practices vary. This variability reflects the heterogeneity of attitudes of the involved clinicians, ethicists, the patient, family and local norms of good clinical and ethical practice (36). Individual patient's, family members and clinicians may regard the continuation of hydration as a nonburdensome humane supportive intervention that represents (and may actually constitute) one means of reducing suffering (57, 58). Alternatively, hydration may be viewed as a superfluous impediment to inevitable death, that does not contribute to patient comfort or the prevailing goals of care and that can be appropriately withdrawn (59). Often, the patient will request relief of suffering and give no direction regarding supportive measures. In this circumstance the family and health care providers must reach consensus as to what constitutes a morally and personally acceptable approach based on the ethical principles of beneficence, non-malfeasance and respect for personhood. In cases where there are religious or culturally based reservations regarding the discontinuation of nutritional support, it should be maintained unless there is evidence of direct patient harm by the intervention. EMERGENCY SEDATION The context In some cases, immediately pre-terminal patients will present with overwhelming symptoms as they are dying. In these situations emergency decisions will need to be made without recourse to a case conference or even cross consultation. This may occur in the setting of a dying patient with sudden onset severe dyspnea (60), agitated delirium (61), massive bleeding or pain. Care planning that anticipates potential emergencies and plans responses can help reduce the stress of emergency decision making in situations such as these. Planning Contingency plans for the management of catastrophic situations should be discussed wit the patient and with family members. If the patient is at home, sedating medications should be prepared and a clear plan for emergency administration should be discussed. In situations in which family members or other home carers feel that they would be unable to administer emergency medications, consideration should be given to inpatient care. Administration As in the previous scenario, midazolam is recommended as the drug of choice. Initial sedation can be achieved with a bolus of 2.5mg SC/IV which can be repeated after 5 minutes if adequate sedation is not achieved. Once the patient is calm a subcutaneous or intravenous infusion can be used. In the immediately pre terminal patient the only salient parameters for ongoing observation are those pertaining to comfort. Symptoms should be assessed until death; observations of pulse blood pressure and temperature are superfluous. Respiratory rate is monitored primarily to ensure that absence of respiratory distress and tachypnea. RESPITE SEDATION The context In many instances, the notion of refractoriness is relative. Among patients who are not imminently dying, severe emotional and physical fatigue influence the patient’s perception of the intolerability of symptoms or of further attempts to alleviate them. Since this may be a reversible phenomenon, sedation is often presented initially as a respite option to provide relief and rest, with a planned restoration of lucidity after an agreed interval. After such respite, some patients will be sufficiently rested to consider further trials of symptomatic therapy (22). Administration There are critical differences in the monitoring of sedation in this setting. In addition to the level of sedation it is essential to monitor routine physiological parameters such as heart rate blood pressure and oxygen saturation. In these cases, the sedating agent should be administered by the lowest effective dose that provides adequate comfort. Despite all of these precautions, sedation of this sort is a potentially unstable situation, and the possibility that lucidity may not be promptly restored or that death is among the risks involved, should be explained to both the patient and family. SEDATION FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL OR EXISTENTIAL SUFFERING The context Patients approaching the end of life often suffer from existential issues include hopelessness, futility, meaninglessness, disappointment, remorse, death anxiety, and disruption of personal identity (62-66). If life is perceived to offer, at best, comfort in the setting of fading potency or, at worst, ongoing physical and emotional distress as days pass slowly until death, anticipation of the future may be associated with feelings of hopelessness, futility, or meaninglessness such that the patient sees no value in continuing to live (64, 66-71). Death anxiety is common among cancer patients; surveys have shown that 50-80% of terminally ill patients have concerns or troubling thoughts about death, and that only a minority achieve an untroubled acceptance of death (67, 72, 73). Together, these symptoms have been labeled a “demoralization syndrome” (74). In a Japanese report, 1 of 240 patients received sedation for the relief of severe existential distress alone, but a further 19 patients who received sedation for other symptoms described their lives as meaningless (75). Specific consideration in this situation Sedation in the management of refractory psychological symptoms and existential diastases is different. By the nature of the symptoms being addressed it is much more difficult to establish that they are truly refractory: the severity of distress of some of these symptoms may be very dynamic and idiosyncratic, the standard treatments have low intrinsic morbidity and for some, like existential distress, there are no well established strategies. Additionally, the presence of these symptoms do not necessarily indicate a far advanced state of physiological deterioration. This factor, compounded with the observations that psychological distress and the desire for death may be very variable (71) and that psychological adaptation and coping is common (76), cast doubt over the issue of proportionality. The dilemma These situations present a major dilemma insofar as neither desirable to subject patients with refractory psychological or existential suffering to protracted trials neither of therapies that provide inadequate relief, nor to sedate patients when viable alternatives remain unexplored. In this setting, as with physical symptoms, refractory psychological or existential distress must, be distinguished from "difficult" problems which have been resistant to relief thus far but which could potentially respond within a tolerable time frame. Published guidelines Guidelines to assist in this situation have been published (77-79) 1. This approach should be reserved for patients in the advanced stages of a terminal illness with a documented do-not-resuscitate order. 2. The designation of such symptoms as refractory should only be done following a period of repeated assessment by clinicians skilled in psychological care who have established a relationship with the patient and his or her family along with trials of routine approaches for anxiety (76), depression (76), and existential distress (80-84) should be reviewed. 3. The evaluation should be made in the context of a case conference since individual clinician bias or burnout can influence decision-making (1, 85, 86). 4. In the rare situations that this strategy is indeed appropriate and proportionate to the situation, it should be initiated on a respite basis with planned downward titration after a pre-agreed interval. It has been reported that respite sedation, can break a cycle of anxiety, distress and catastrophizing that precipitates requests of this kind. Only after repeated trials of respite sedation with intensive intermittent therapy, should continuous sedation be considered. ETHICAL CONSIDERATUIONS Sedation to relieve otherwise intolerable suffering for patients who are dying as normative practice There is no distinct ethical problem in the use of sedation to relieve otherwise intolerable suffering for patients who are dying. Rather, the decision making and application of this therapeutic option represents a continuum of good clinical practice. Good clinical practice is predicated on careful patient evaluation (as previously described) which incorporates assessment of current goals of care. Since all medical treatments involve risks and benefits, each potential option must be evaluated for their potential to achieve the goals of care. Where risks of treatment are involved, the risks must be proportionate to the gravity of the clinical indication. In these deliberations, clinician considerations are guided by an understanding of the goals of care and must be within accepted medical guidelines of beneficence and non-malfeasance. Finally, the penultimate decision to act on these considerations depends on informed consent or advanced directive of the patient. In this clinical context, the decision to offer the use of sedation to relieve intolerable suffering to terminally ill patients, presents no new ethical problem (85, 87). As with any other high risk clinical practice, potential for non beneficent abuse exists. Wein has described prerequisites to ensuring that sedation of imminently dying remains on an ethically sound footing (28): Appropriate patient selection, candor and consent, cross-consolation, documentation, knowledge of medications and illness and a commitment to titrate and monitor Despite the potential for shortening life, this approach has been endorsed as acceptable normative practice by legal precedent (88). In the 1957 English case of R v Adams, Justice Devin wrote in his judgment “If the first purpose of medicine, the restoration of health, can no longer be achieved, there is still much for a doctor to do, and he is entitled to do all that is proper and necessary to relieve pain and suffering, even if the measures he takes may incidentally shorten life.” He justified this approach rejecting the notion that this is a special defense, but rather by endorsing the clinical pragmatist approach that “The cause of death is the illness or the injury, and the proper medical treatment that is administered and that has an incidental effect on determining the exact moment of death is not the cause in any sensible use of the term “(89). This approach was lent further support by the recent decision of the Supreme Court of the United States rejected a constitutional right that encompasses assisted suicide but endorsed the use of sedation as an extreme form of palliative care in the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life (90). Potential for Abuse Undoubtedly the use of sedation in the relief of symptoms at the end of life is potentially open to abuse. Indeed, some physicians administer doses of medication, ostensibly to relieve symptoms but with a covert intention of hastening the patient's death. Data from the Netherlands indicated that administration of sedating medication, ostensibly to relieve distress but with manifest intent of hastening death is commonplace (91, 92). In a recent survey of Dutch physicians who dad sued sedation at the end of life, hastening death was partly the intention of the physician in 47% (CI, 41% to 54%) of cases and the explicit intention in 17% (CI, 13% to 22%) of cases (93). Research in Australia (94, 95) and the United States (96, 97) indicate that this practice is not uncommon. An Australian survey of 683 general surgeons found that 36% had given drugs in doses that they perceived to be greater than those required to relieve symptoms with the intention of hastening death (98). Similar practices, albeit much less common, were reported in a survey of end of life care practices in 6 European countries (99). These duplicitous practices represent an unacceptable deviation from normative ethical clinical practice. Infrastructural guidelines are necessary to avoid deceitful practices of this kind. Distinction from “Slow Euthanasia” Some authors argue that although sedation in the relief of uncontrolled symptoms may be justifiable, the concurrent discontinuation of nutrition and hydration does not contribute to patient comfort and almost certainly hastens death by starvation and dehydration. Consequently, they argue, sedation for the management of refractory symptoms is practically the same as “slow euthanasia” (58, 100-102). This proposition is argued both by opponents to euthanasia, who are concerned about harmful aspects of the practice of forgoing nutrition and hydration (58, 100-103), and also by proponents of elective death who argue that if these acts are morally equivalent, then the more rapid mode of elective death, such as euthanasia or assisted suicide, is more humane and dignified (53, 54). Another concern is that the since sedation may hasten the death of the patient, that the plea of no moral responsibility for foreseen, inevitable untoward outcomes is at best, spurious, or at worst dishonest (104). This relates to the so called “Doctrine of Double Effect” which will be discussed in the subsequent section. Whilst we absolutely reject the appropriateness of the term "Slow Euthanasia" we feel that it important to address this charge. With regard to the first concern, it is important to reassert that, contrary to the assertions of Quill (53, 54) and Orentlicher (55) the discontinuation of hydration and nutrition is not an essential element to the administration of sedation in the management of refractory symptoms (See "Nutrition and Hydration" below). Furthermore, there is no data to support the assertion that it is "typical" (105). We hold that sedation in the management of refractory symptoms is distinct from euthanasia insofar as: the intent of the intervention is to provide symptom relief not to end the life of the suffering patient 2) the intervention is proportionate to the prevailing symptom, its severity and the prevailing goals of care and finally and, most importantly 3) unlike euthanasia or assisted suicide, the death of the patient is not a criteria for the success of the treatment. Distinction from Euthanasia Euthanasia refers to the deliberate termination of the life of a patient by active intervention, at the request of the patient in the setting of otherwise uncontrolled suffering. This is distinct from physician assisted suicide by the physician provides the means of suicide and instruction to a patient to facilitate successful suicide. The use of sedation to relieve otherwise unendurable symptoms at the end of life falls under the rubric of "the provision of a potentially lethal medication for a patient with a narrow therapeutic index". Clearly this situation may result in the inadvertent foreshortening of the patient’s life either by direct action of the drug or as an adverse effect (such as aspiration). The use of sedation in this setting is critically distinct from euthanasia for two fundamental reasons: Firstly, the intent of the intervention is to provide symptom relief the intervention is proportionate to the prevailing symptom, its severity and the prevailing goals of care and, secondly and most importantly, the death of the patient is not a criterion for the success of the treatment. The Doctrine of Double Effect In cases where a contemplated action has both good effects and bad effects the doctrine provides an approach to answer the question: “Do the means justify the end? According to “Double effect ethics”, an action is permissible if it is not wrong in itself and it does not require that one directly intend the bad result. Double effect ethics assume the integrity of the physician and unambiguous intent and motive. Classically 5 criteria have been described to evaluate the validity of a double effect claim (106): 1) The action is either morally good or is morally neutral 2) The undesired yet foreseen untoward result is not directly intended 3) The good effect is not a direct result of the foreseen untoward effect 4) The good effect be "proportionate to" the untoward effect. 5) That there be no other way to achieve the desired ends without the untoward effect The “Doctrine of Double Effect“ is problematic insofar as it does not always apply to the use of sedation in the management of refractory symptoms. When sedation is used to relieve otherwise refractory pain and suffering at the end of life, the intention is to relieve otherwise unendurable suffering. The untoward consequences that are foreseen include the possibility of foreshortened survival alone and the definite loss of interactional function. Since the death of the patient at the end of a long and difficult illness is not always perceived as untoward, there is a significant problem with the application of the double-effect justification. Indeed, in Jewish tradition, there is a blessing for a “timely” death, “Baruch Dayan Ha Emet” (Blessed is the Supreme Judge). Thus, to call the potential for foreshortened survival a "bad outcome" may, in some cases, be inaccurate (at best) or dishonest (at worst). Since the moral justification of sedation by Double Effect requires that clinicians make unequivocal claims regarding the undesirability of the possibility of the patient's death, it is often inappropriate (104). Indeed, it undermines the essential element of clinician credibility. This view regarding the “Double Effect” justification for the use of sedation is supported by other critics who have claimed that, at worst it has become a meaningless mantra recited by cynical surreptitious practitioners of euthanasia cloaked as palliative care clinicians (102). It is prudent and appropriate to emphasize that there is no clear evidence that the use of sedation in the relief of refractory symptoms at the end of life foreshortens survival. Three studies have addressed this issue in the setting of hospice care (23, 107, 108). Three studies have addressed this issue on the management of patients with terminal dyspnea after withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (109-111). In the latter setting, the studies found no correlation between level of sedation, dose of sedatives and duration of survival until death. Ethical issues regarding Nutrition and hydration when patients are sedated Although sedation is clearly beneficent in terms of providing relief of otherwise intolerable suffering, the beneficence of withdrawal of nutrition and hydration in the already sedated and comfortable patient is not self-evident, and indeed it may be perceived as harmful. This debate has both medical and ethical dimensions. Medically, there is little data to support the clinical benefit of hydration or artificial nutrition in the imminently dying, or to suggest that it prolongs life or contributes to comfort (112-114). Ethically, the withdrawal of potentially death deferring treatments (such as hydration) among dying patients is, for some, controversial (57, 58). For reasons of clarity, the issue of sedation must be distinguished from the distinct and separate issue of hydration. Opinions and practices vary. This variability reflects the heterogeneity of attitudes of the involved clinicians, ethicists, the patient, family and local norms of good clinical and ethical practice (36). Individual patient's, family members and clinicians may regard the continuation of hydration as a nonburdensome humane supportive intervention that represents (and may actually constitute) one means of reducing suffering (57, 58). Alternatively, hydration may be viewed as a superfluous impediment to inevitable death, that does not contribute to patient comfort or the prevailing goals of care and that can be appropriately withdrawn (59). Often, the patient will request relief of suffering and give no direction regarding supportive measures. In this circumstance the family and health care providers must reach consensus as to what constitutes a morally and personally acceptable approach based on the ethical principles of beneficence, non-malfeasance and respect for personhood. In cases where there are religious or culturally based reservations regarding the discontinuation of nutritional support, it should be maintained unless there is evidence of direct patient harm by the intervention. CONCLUSIONS Sedation is a critically important therapeutic tool of last resort. It enables the clinician to provide relief from intolerable distress when other options are not adequately effective. Because sedation undermines the capacity to interact, it must be used judiciously. Clear indications and guidelines for use are necessary to prevent abuse of this approach to facilitate the deliberate killing of patients, which while benevolently intended, may have untoward sociological and ethical consequences for palliative care clinicians and the image of palliative medicine as a profession. Table 1: Surveys of the use of sedation in the management of refractory symptoms Year N Place % Sedated reference for refectory symptoms Ventafridda 1990 120 home 52% (19) Fainsinger 1991 100 inpatient 16% (21) Morita 1996 143 hospice 43% (22) Stone 1997 115 IP and Home 26% (23) Fainsinger 1998 76 IP hospice 30% (24) Chiu 2001 251 IP palliative care 28% (115) Muller Busch 2002 548 IP palliative care 14% (116) Morita 2004 Multi center <10-50% (117) References 1. Cherny NI, Portenoy RK. Sedation in the management of refractory symptoms: guidelines for evaluation and treatment. J Palliat Care 1994;10(2):31-8. 2. del Rosario MA, Martin AS, Ortega JJ, Feria M. Temporary sedation with midazolam for control of severe incident pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;21(5):439-42. 3. Rousseau PC. Palliative sedation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002;19(5):295-7. 4. Jackson WC. Palliative sedation vs. terminal sedation: what's in a name? Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002;19(2):81-2. 5. Beel A, McClement SE, Harlos M. Palliative sedation therapy: a review of definitions and usage. Int J Palliat Nurs 2002;8(4):190-9. 6. Cowan JD, Walsh D. Terminal sedation in palliative medicine--definition and review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 2001;9(6):403-7. 7. Mercadante S. Pain treatment and outcomes for patients with advanced cancer who receive followup care at home [see comments]. Cancer 1999;85(8):1849-58. 8. Salisbury C, Bosanquet N, Wilkinson EK, Franks PJ, Kite S, Lorentzon M, et al. The impact of different models of specialist palliative care on patients' quality of life: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 1999;13(1):3-17. 9. Higginson IJ, Wade AM, McCarthy M. Effectiveness of two palliative support teams. J Public Health Med 1992;14(1):50-6. 10. Higginson IJ, McGregor AM. The impact of palliative medicine? [editorial]. Palliat Med 1999;13(4):285-98. 11. Peruselli C, Di Giulio P, Toscani F, Gallucci M, Brunelli C, Costantini M, et al. Home palliative care for terminal cancer patients: a survey on the final week of life. Palliat Med 1999;13(3):233-41. 12. Higginson IJ, Hearn J. A multicenter evaluation of cancer pain control by palliative care teams. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;14(1):29-35. 13. Conill C, Verger E, Henriquez I, Saiz N, Espier M, Lugo F, et al. Symptom prevalence in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;14(6):328-31. 14. Storey P. Symptom control in advanced cancer. Semin Oncol 1994;21(6):748-53. 15. Lichter I, Hunt E. The last 48 hours of life. J Palliat Care 1990;6(4):7-15. 16. Johanson GA. Symptom character and prevalence during cancer patients' last days of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1991;8(2):6-8, 18. 17. Enck RE. Drug-induced terminal sedation for symptom control. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1991;8(5):3-5. 18. Roy DJ. Need they sleep before they die? J Palliat Care 1990;6(3):3-4. 19. Ventafridda V, Ripamonti C, De Conno F, Tamburini M, Cassileth BR. Symptom prevalence and control during cancer patients' last days of life. J Palliat Care 1990;6(3):7-11. 20. Mount B. A final crescendo of pain? J Palliat Care 1990;6(3):5-6. 21. Fainsinger R, Miller MJ, Bruera E, Hanson J, Maceachern T. Symptom control during the last week of life on a palliative care unit. J Palliat Care 1991;7(1):5-11. 22. Morita T, Inoue S, Chihara S. Sedation for symptom control in Japan: the importance of intermittent use and communication with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12(1):32-8. 23. Stone P, Phillips C, Spruyt O, Waight C. A comparison of the use of sedatives in a hospital support team and in a hospice. Palliat Med 1997;11(2):140-4. 24. Fainsinger RL, Landman W, Hoskings M, Bruera E. Sedation for uncontrolled symptoms in a South African hospice. J Pain Symptom Manage 1998;16(3):145-52. 25. Coyle N. The last four weeks of life. Am J Nurs 1990;90(12):75-6, 78. 26. Feldman HA, McKinlay JB, Potter DA, Freund KM, Burns RB, Moskowitz MA, et al. Nonmedical influences on medical decision making: an experimental technique using videotapes, factorial design, and survey sampling. Health Serv Res 1997;32(3):343-66. 27. Christakis NA, Asch DA. Biases in how physicians choose to withdraw life support. Lancet 1993;342(8872):642-6. 28. Wein S. Sedation in the imminently dying patient. Oncology (Huntingt) 2000;14(4):585-92; discussion 592, 597-8, 601. 29. Braun TC, Hagen NA, Clark T. Development of a clinical practice guideline for palliative sedation. J Palliat Med 2003;6(3):345-50. 30. Haines IE, Zalcberg J, Buchanan JD. Not-for-resuscitation orders in cancer patients--principles of decision-making. Med J Aust 1990;153(4):225-9. 31. Rosner F, Kark PR, Bennett AJ, Buscaglia A, Cassell EJ, Farnsworth PB, et al. Medical futility. Committee on Bioethical Issues of the Medical Society of the State of New York. N Y State J Med 1992;92(11):485-8. 32. Marik PE, Zaloga GP. CPR in terminally ill patients? Resuscitation 2001;49(1):99-103. 33. Portenoy RK. Continuous intravenous infusion of opioid drugs. Med Clin North Am 1987;71(2):233-41. 34. Potter JM, Reid DB, Shaw RJ, Hackett P, Hickman PE. Myoclonus associated with treatment with high doses of morphine: the role of supplemental drugs [see comments]. BMJ 1989;299(6692):150-3. 35. Dunlop RJ. Excitatory phenomena associated with high dose opioids. Curr Ther 1989;30(6):121123. 36. Chater S, Viola R, Paterson J, Jarvis V. Sedation for intractable distress in the dying--a survey of experts. Palliat Med 1998;12(4):255-69. 37. Nordt SP, Clark RF. Midazolam: a review of therapeutic uses and toxicity. J Emerg Med 1997;15(3):357-65. 38. Burke AL. Palliative care: an update on "terminal restlessness". Med J Aust 1997;166(1):39-42. 39. Collins P. Prolonged sedation with midazolam or propofol [letter; comment]. Crit Care Med 1997;25(3):556-7. 40. Johanson GA. Midazolam in terminal care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1993;10(1):13-4. 41. Power D, Kearney M. Management of the final 24 hours. Ir Med J 1992;85(3):93-5. 42. Burke AL, Diamond PL, Hulbert J, Yeatman J, Farr EA. Terminal restlessness--its management and the role of midazolam [see comments]. Med J Aust 1991;155(7):485-7. 43. Greene WR, Davis WH. Titrated intravenous barbiturates in the control of symptoms in patients with terminal cancer. South Med J 1991;84(3):332-7. 44. Truog RD, Berde CB, Mitchell C, Grier HE. Barbiturates in the care of the terminally ill. N Engl J Med 1992;327(23):1678-82. 45. Oliver DJ. The use of methotrimeprazine in terminal care. Br J Clin Pract 1985;39(9):339-40. 46. O'Neill J, Fountain A. Levomepromazine (methotrimeprazine) and the last 48 hours. Hosp Med 1999;60(8):568-70. 47. McIver B, Walsh D, Nelson K. The use of chlorpromazine for symptom control in dying cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 1994;9(5):341-5. 48. LeGrand SB. Dyspnea: the continuing challenge of palliative management. Curr Opin Oncol 2002;14(4):394-8. 49. Tobias JD. Propofol sedation for terminal care in a pediatric patient. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1997;36(5):291-3. 50. Krakauer EL, Penson RT, Truog RD, King LA, Chabner BA, Lynch TJ, Jr. Sedation for intractable distress of a dying patient: acute palliative care and the principle of double effect. Oncologist 2000;5(1):53-62. 51. Mercadante S, De Conno F, Ripamonti C. Propofol in terminal care. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995;10(8):639-42. 52. Moyle J. The use of propofol in palliative medicine. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995;10(8):643-6. 53. Quill TE, Lo B, Brock DW. Palliative options of last resort: a comparison of voluntarily stopping eating and drinking, terminal sedation, physician-assisted suicide, and voluntary active euthanasia. JAMA 1997;278(23):2099-104. 54. Quill TE, Byock IR. Responding to intractable terminal suffering: the role of terminal sedation and voluntary refusal of food and fluids. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med 2000;132(5):408-14. 55. Orentlicher D, Caplan A. The Pain Relief Promotion Act of 1999: a serious threat to palliative care. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1999;27(4):527-39; discussion 540-5. 56. Bozzetti F, Amadori D, Bruera E, Cozzaglio L, Corli O, Filiberti A, et al. Guidelines on artificial nutrition versus hydration in terminal cancer patients. European Association for Palliative Care. Nutrition 1996;12(3):163-7. 57. Jansen LA, Sulmasy DP. Sedation, alimentation, hydration, and equivocation: careful conversation about care at the end of life. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(11):845-9. 58. Craig GM. On withholding artificial hydration and nutrition from terminally ill sedated patients. The debate continues [published erratum appears in J Med Ethics 1996 Dec;22(6):361]. J Med Ethics 1996;22(3):147-53. 59. Ashby M, Stoffell B. Artificial hydration and alimentation at the end of life: a reply to Craig. J Med Ethics 1995;21(3):135-40. 60. Campbell ML. Terminal dyspnea and respiratory distress. Crit Care Clin 2004;20(3):403-17, viiiix. 61. Kress JP, Hall JB. Delirium and sedation. Crit Care Clin 2004;20(3):419-33, ix. 62. Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med 1982;306(11):639-45. 63. Moberg DO, Brusek PM. Spiritual well-being: a neglected subject in quality of life research. Social Indicators Research 1978;5:303-323. 64. Yalom ID. Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 1980. 65. Kissane DW. Psychospiritual and existential distress. The challenge for palliative care. Aust Fam Physician 2000;29(11):1022-5. 66. Ellis JB, Smith PC. Spiritual well-being, social desirability and reasons for living: is there a connection? Int J Soc Psychiatry 1991;37(1):57-63. 67. Bolmsjo I. Existential issues in palliative care--interviews with cancer patients. J Palliat Care 2000;16(2):20-4. 68. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Kaim M, Funesti-Esch J, Galietta M, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. Jama 2000;284(22):290711. 69. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld BD. Physician-Assisted Suicide: The Influence of Psychosocial Issues. Cancer Control 1999;6(2):146-161. 70. Chochinov HM, Tataryn D, Clinch JJ, Dudgeon D. Will to live in the terminally ill. Lancet 1999;354(9181):816-9. 71. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Mowchun N, Lander S, Levitt M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(8):1185-91. 72. Neubauer BJ, Lai JY. Death anxiety and attitudes toward hospice care. Psychol Rep 1988;63(1):195-8. 73. Stedeford A. Couples facing death. I-Psychosocial aspects. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;283(6298):1033-6. 74. Kissane DW, Clarke DM, Street AF. Demoralization syndrome--a relevant psychiatric diagnosis for palliative care. J Palliat Care 2001;17(1):12-21. 75. Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. Terminal sedation for existential distress. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2000;17(3):189-95. 76. Breitbart W, Chochinov HM, Passik SD. Psychiatric aspects of palliative care. In: Doyle D, Hanks GW, MacDonald N, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 933-954. 77. Cherny NI. Commentary: sedation in response to refractory existential distress: walking the fine line. J Pain Symptom Manage 1998;16(6):404-6. 78. Rousseau P. Existential suffering and palliative sedation: a brief commentary with a proposal for clinical guidelines. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2001;18(3):151-3. 79. Rousseau P. Careful conversation about care at the end of life. Ann Intern Med 2002;137(12):1008-10; author reply 1008-10. 80. Kissane DW, Bloch S, Miach P, Smith GC, Seddon A, Keks N. Cognitive-existential group therapy for patients with primary breast cancer--techniques and themes. Psychooncology 1997;6(1):25-33. 81. Georgesen J, Dungan JM. Managing spiritual distress in patients with advanced cancer pain. Cancer Nurs 1996;19(5):376-83. 82. Millison MB. Spirituality and the caregiver. Developing an underutilized facet of care. Am J Hosp Care 1988;5(2):37-44. 83. Stepnick A, Perry T. Preventing spiritual distress in the dying client. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 1992;30(1):17-24. 84. Speck PW. Spiritual issues in palliative care. In: Doyle D, Hanks GW, MacDonald N, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 804-814. 85. Fins JJ, Bacchetta MD, Miller FG. Clinical pragmatism: A method of moral problem solving. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 1997;7:129-145. 1997;7:129-145. 86. Cherny NI, Coyle N, Foley KM. The treatment of suffering when patients request elective death. J Palliat Care 1994;10(2):71-9. 87. Miller FG, Fins JJ, Bacchetta MD. Clinical pragmatism: John Dewey and clinical ethics. J Contemp Health Law Policy 1996;13(1):27-51. 88. Gevers S. Terminal sedation: a legal approach. Eur J Health Law 2003;10(4):359-67. 89. Devlin P. Easing the Passing. London: Bodley Head; 1985. 90. Burt RA. The Supreme Court speaks--not assisted suicide but a constitutional right to palliative care. N Engl J Med 1997;337(17):1234-6. 91. van der Maas PJ, van Delden JJ, Pijnenborg L. Euthanasia and other medical decisions concerning the end of life. An investigation performed upon request of the Commission of Inquiry into the Medical Practice concerning Euthanasia. Health Policy 1992;21(1-2):vi-x, 1-262. 92. van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, Haverkate I, de Graaff CL, Kester JG, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide, and other medical practices involving the end of life in the Netherlands, 1990-1995 [see comments]. N Engl J Med 1996;335(22):1699-705. 93. Rietjens JA, van der Heide A, Vrakking AM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G. Physician reports of terminal sedation without hydration or nutrition for patients nearing death in the Netherlands. Ann Intern Med 2004;141(3):178-85. 94. Kuhse H, Singer P, Baume P, Clark M, Rickard M. End-of-life decisions in Australian medical practice. Med J Aust 1997;166(4):191-6. 95. Stevens CA, Hassan R. Management of death, dying and euthanasia: attitudes and practices of medical practitioners in South Australia. Arch Intern Med 1994;154(5):575-84. 96. Willems DL, Daniels ER, van der Wal G, van der Maas PJ, Emanuel EJ. Attitudes and practices concerning the end of life: a comparison between physicians from the United States and from The Netherlands [In Process Citation]. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(1):63-8. 97. Meier DE, Emmons CA, Wallenstein S, Quill T, Morrison RS, Cassel CK. A national survey of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia in the United States [see comments]. N Engl J Med 1998;338(17):1193-201. 98. Douglas CD, Kerridge IH, Rainbird KJ, McPhee JR, Hancock L, Spigelman AD. The intention to hasten death: a survey of attitudes and practices of surgeons in Australia. Med J Aust 2001;175(10):511-5. 99. van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E, et al. End-of-life decisionmaking in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet 2003;362(9381):345-50. 100. Craig GM. On withholding nutrition and hydration in the terminally ill: has palliative medicine gone too far? [see comments]. J Med Ethics 1994;20(3):139-43; discussion 144-5. 101. Craig G. Is sedation without hydration or nourishment in terminal care lawful? Med Leg J 1994;62(Pt 4):198-201. 102. Orentlicher D. The Supreme Court and physician-assisted suicide--rejecting assisted suicide but embracing euthanasia. N Engl J Med 1997;337(17):1236-9. 103. Brody H. Causing, intending, and assisting death. J Clin Ethics 1993;4(2):112-7. 104. Quill TE, Dresser R, Brock DW. The rule of double effect--a critique of its role in end-of-life decision making. N Engl J Med 1997;337(24):1768-71. 105. Sulmasy DP, Ury WA, Ahronheim JC, Siegler M, Kass L, Lantos J, et al. Palliative treatment of last resort and assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med 2000;133(7):562-3. 106. Boyle J. Medical ethics and double effect: the case of terminal sedation. Theor Med Bioeth 2004;25(1):51-60. 107. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Lue BH, Cheng SY, Chen CY. Sedation for refractory symptoms of terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;21(6):467-72. 108. Sykes N, Thorns A. Sedative Use in the Last Week of Life and the Implications for End-of-Life Decision Making. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(3):341-4. 109. Daly BJ, Thomas D, Dyer MA. Procedures used in withdrawal of mechanical ventilation [see comments]. Am J Crit Care 1996;5(5):331-8. 110. Campbell ML, Bizek KS, Thill M. Patient responses during rapid terminal weaning from mechanical ventilation: a prospective study [see comments]. Crit Care Med 1999;27(1):73-7. 111. Wilson WC, Smedira NG, Fink C, McDowell JA, Luce JM. Ordering and administration of sedatives and analgesics during the withholding and withdrawal of life support from critically ill patients [see comments]. Jama 1992;267(7):949-53. 112. Ahronheim JC. Nutrition and hydration in the terminal patient. Clin Geriatr Med 1996;12(2):37991. 113. Barber MD, Fearon KC, Delmore G, Loprinzi CL. Should cancer patients with incurable disease receive parenteral or enteral nutritional support? Eur J Cancer 1998;34(3):279-85. 114. Koshuta MA, Schmitz PJ, Lynn J. Development of an institutional policy on artificial hydration and nutrition. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 1991;1(2):133-9; discussion 139-40. 115. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Lue BH, Cheng SY, Chen CY. Sedation for refractory symptoms of terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;21(6):467-72. 116. Muller-Busch HC, Andres I, Jehser T. Sedation in palliative care - a critical analysis of 7 years experience. BMC Palliat Care 2003;2(1):2. 117. Morita T. Differences in physician-reported practice in palliative sedation therapy. Support Care Cancer 2004.