Self-concept and self-esteem: How do the different views of self

advertisement

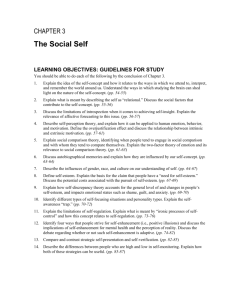

Consider the impact of self-concept development and self esteem on teaching and learning. Purkey (1988) argues that the theories of self-concept development started with Rene Descartes and his idea, published in Principles of Philosophy (1644), that if he doubted, he was thinking and if he was thinking, he must exist. A second milestone was the work of Sigmund Freud. Although Freud did not explicitly mention self-concept in his theories and proved to be more influential in the context of counselling (Purkey, 1988), he provided a new understanding of internal mental processes that informed the work of others in the field of child development (Keenan, 2002; Burns, 1982). The development of the self-concept and the enhancement of self-esteem are now considered to be a major outcome of education (Fontana, 1995). Self-concept is seen as being a major determinant of learning and behaviour (Burns, 1982), whilst Mosley points out that “research has constantly shown a direct link between the enhancement of self-esteem and the rising of academic achievement” (1993: p12). For Burns, an understanding of self-concept development and its relationship with self-esteem is essential for teachers “to understand children, help some maintain and enhance positive views about themselves, and help others to change their views” (1982: p31). Consequently, this essay will consider the impact of self-concept development and its relationship with self-esteem on teaching and learning. The first section will define the term ‘selfconcept’ and discuss the many diffuse theories relating to its development, particularly those of James, Cooley, Mead, Erikson and Rogers. The second section will look more closely at self-esteem, drawing on the author’s own experience to discuss the effects of pupil self-concepts on learning and teaching. Lawrence defines self-concept as “the sum total of an individual’s mental and physical characteristics and his/her evaluation of them” (In Pollard, 2002: p102); 1 whilst Burns argues that self-concept is “composed of all the beliefs and evaluations you have about yourself” (1982: p1). Lawrence (In Pollard, 2002) suggests that selfconcept can be divided into three areas of development: self-image, ideal self and self-esteem, whilst Burns (1982) uses the terms ‘descriptive’ for self-image and ‘evaluative’ for self-esteem. Both Burns (1982) and Lawrence (ibid) agree that selfconcept not only determines who you are, but who you think you are, what you think you are capable of becoming and what you think you can do. Most researchers acknowledge that the development of self-concept is both social and environmental – that it is developed through interaction with significant others and by the evaluation of personal experiences (Burns, ibid; Keenan, 2002; Fontana, 1977). Burns (1982) suggests that the four main theories dealing with the development of self-concept are those of James, Cooley and Mead, Erikson and Rogers. William James (1890) was the first psychologist to work on the development of self-concept. Prior to that, it had mainly been a topic for philosophers (Burns, 1982; Lawrence, ibid). James believed that newborn babies find the world a “booming, buzzing confusion” (1890) and that in order for them to make sense of the world around them, perceptual development was needed. James argued that the ‘self’ was made up of a subjective self and an objective self, or the ‘I’ and ‘Me’, where ‘I’ is a consciousness of existence and the ‘Me’ is the individual characteristics that make us different from everybody else (James, 1890; Mussen et al, 1984). James suggested that the objective self was made up four components: the spiritual self, the material self, the social self and the bodily self (Burns, 1982). James acknowledged the criticism that it was implausible for the ‘Me’ to be separated from the ‘I’ (Burns, 1982). As Burns points out, “while language allows us to categorize in terms of knower and the known, they are […] discriminated aspects of the singularity of experience” (1982: p15). In other words, we are simultaneously ‘I’ and ‘Me’. The interaction between the ‘ideal self’ and reality is an important aspect of James’s work 2 (Burns, 1982). James argues that for each of our objective ‘selves’ we have an ‘ideal self’ and that success or failure in achieving this ideal determines our level of selfesteem (Burns, 1982). Failure to achieve our ‘ideal self’ will lead to one of three positions: (1) a rationalization of why we didn’t achieve our ideal, (2) a lowering of expectations or (3) taking other action (Burns, 1982). For James, our expectations were personal and self-imposed and the achievement of our ‘ideal self’ always led to higher self esteem (Burns, 1982), but this has been criticised for failing to take into account the attitudes and opinions of others. As Burns suggests, “there are some skills and jobs which society does not rate very highly, so to consider oneself as the most competent dustman […] is unlikely to lead to high self-esteem (1982, p16). The relationship between the individual, other people and society at large was central to the work of G H Mead (1913) and C H Cooley, who became known as ‘symbolic integrationists’ (Pollard & Filer, 1996). Symbolic integrationists believe that humans respond to the individual meanings that their environment has for them and that these meanings are made through social interaction, further modified by individual interpretation (Burns, 1982). Cooley argued that “self and society are twin born […] and the notion of a separate and independent ego is an illusion” (1912, p5 cited in Burns, 1982: p17). In other words, an individual’s actions are modified by society and vice-versa. Cooley’s ‘looking glass theory of self’ postulated that selfconcept is heavily influenced not only by the feedback an individual receives from others, and particularly significant others, but by what that individual believes others think of them (Lawrence, 2002; Burns, 1982). Mead agreed with James that the ‘self’ could be divided into ‘I’ and ‘Me’ (Fontana, 1995; Mead, 1913), but took a more Vygotskian view about how self-concept developed (Pollard & Filer, ibid). Mead believed that the development of the ‘self’ was a social process in which an individual learns the complex set of shared symbols that make up a culture (Burns, 1982; Pollard & Filer, ibid). Through this, not only are “objects, actions and characteristics 3 defined, but the individual is also defined” (Burns, 1982: p18). Like Vygotsky, Mead believed that language was an essential element in development and that it was a precursor to self-awareness and action (Pollard & Filer, ibid). Although Mead saw ‘self’ as a simultaneous ‘Me’ and ‘I’, his definition differed from that of James in an important way (Burns, 1982). Mead saw the ‘I’ as similar to Freud’s ‘Id’, impulsive and undisciplined, whilst the ‘Me’ was the incorporated meanings and values of others, similar to Freud’s ‘super-ego’ (Burns, 1982). As Burns suggests, the “’I’ provides the propulsion; ‘Me’ provides direction” (1982, p18). Erikson also drew upon Freud’s work and like Cooley and Mead, emphasized the social and cultural factors of development (Keenan, 2002). Erikson, however, did not like the terms ‘self-conceptualisation’, ‘self-image’ or ‘self-esteem’, preferring instead to talk of ‘Identity’ (Burns, 1982; Crain, 1992). Erikson also differed to Mead and Cooley in that he saw process of identity formation as the interaction between three systems, the ‘somatic’ or biological process, the ‘ego’ or reasoning process and the ‘societal’, the process of integration into society (Keenan, 2002). Erikson argued that identity formation was a life long process that continued through old age (Keenan, 2002), arguing, “identity is never established [and is not] static and unchangeable” (1968: p24 cited in Burns, 1982: p19). Erikson proposed eight stages of development that progressed in an orderly sequence. At each stage, the individual is faced with a unique crisis and it is how well the crisis is resolved that determines the nature of further development (Keenan, 2002; Burns 1982; Crain, 1992). Erikson defined his development stages and their challenges as: (1) Trust vs. Mistrust (Birth to 1 Year) – Developing a sense of trust in caregivers, the environment and one’s self; (2) Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (1 to 3 Years) – Developing a sense of one’s autonomy and independence from the caregiver; (3) Initiative vs. Guilt (3 to 6 Years) – Developing a sense of mastery over aspects of one’s environment, coping with challenges and assumption of increasing 4 responsibility; (4) Industry vs. Inferiority (6 to Adolescence) – Mastering intellectual and social challenges; (5) Identity vs. Identity Diffusion (Adolescence) – Developing self identity or a knowledge of what kind of person you are; (6) Intimacy vs. Isolation (20 to 40 Years) – Developing stable and intimate relationships with another person; (7) Generativity vs. Stagnation (40 to 60 Years) – Creating something (e.g. children or something more abstract) to avoid feelings of stagnation; (8) Integrity vs. Despair (Old Age) – Evaluating one’s life by looking back (Keenan, 2002). Successfully negotiating the challenge at a particular stage would lead to high self esteem, or what Keenan describes as a “healthier development outcome” (2002: p22). Unsuccessfully resolving the crisis would not only lead to an unhealthy development outcome and low self-esteem, but also have implications for the future because “at each stage of development, the accomplishments from the previous stage serve as resources to be applied towards mastering the present crisis” (Keenan, 2002: p22). White (1960, in Crain, 1992) criticized Erikson for trying too hard to link aspects of Freud’s ego development into his theories, whilst Miller described Erikson’s theory as a “series of loosely connected ideas lacking systematic quality, rather than a coherent theory of development” (1993, in Keenan, 2002: p23). Keenan (2002) also points out that Erikson’s does not explain the mechanism by which an individual moves between each stage and that it is impossible to empirically test his theories. Despite these criticisms, Erikson’s theories continue to be important, particularly in education psychology, where his work gives us “a relatively clear picture of what mature individuals are like” (Fontana, 1995: p273). Carl Rogers and George Kelly’s view of self-concept development is usually described as ‘humanistic’ or ‘phenomenological’ (Burns, 1982), because it is concerned with the individual’s personal, subjective, view of the world (Fontana, 1995). This contrasts with Erikson, Mead and Cooley, who attempted to understand man “through the eyes of an observer” (Burns, 1982: p19). In other words, Rogers 5 and Kelly wanted to find out how individuals viewed themselves and to discover how and why their needs, feelings, values, beliefs and perceptions make them behave in the way they do (Burns, 1982). Rogers argues that self-concept development takes place through the interaction between two concepts: the ‘organism’ and the ‘self’ (Fontana, 1995). The ‘organism’ is defined as the whole person and includes our survival instinct, feelings, emotions, social needs and most importantly, our need to be accepted and approved by others (Fontana, 1995). If the organism’s needs are met, then the individual develops a ‘self’ in congruence with the ‘organism’. If the organism’s needs are not met, there is an incongruence that can lead to inner conflict, low self-esteem and feelings of rejection (Fontana, 1995). Although Rogers emphasizes the conflict between the ‘organism’ and the ‘self’ as the source of selfconcept, he does acknowledge the concept of an ‘ideal self’ (Burns, 1982), which Fontana describes as “the picture we carry within us of the kind of person we would like to be” (1995: p256). Rogers accepted that a gap or conflict between our ‘ideal self’ and reality would also cause an incongruence and inner conflict (Fontana, 1995; Burns, 1982). Rogers’s theories have been criticised for excluding critical variables from investigation, in particular his emphasising of ‘distortion’ over ‘denial’ as the way individuals cope with a state of incongruity (Burns, 1982). Rogers argues that ‘distortion’ allows experiences to be made consistent with the individual’s selfconcept, whilst ‘denial’ simply removes the experience and renders it unsymbolised (Burns, 1982). As Burns asks, “If denial leaves an experience completely unsymbolised, how can a phenomenological approach ever deal with such a process?” (1982: p22). George Kelly believed that humans are innately curious and make sense of the world by “experimenting, constructing hypotheses about reality, predicting the future, working out strategies and procedures” (Fontana, 1995: p258). The result of this exploration is that we have ‘personal constructs’ about every part of our lives, including ourselves, and that we interpret and respond to reality through these constructs (Fontana, 1995). Kelly’s theories are particularly important for 6 educationalists because they suggest that a child’s constructs about school will influence their educational progress (Fontana, 1995; 1977). Fontana (1995) argues that children are more likely to achieve if they enjoy the experience of school, and that they will enjoy school only if they have created positive constructs about school. The theories of Mead, Cooley, Erikson, Rogers and Kelly have attempted to show how we build up knowledge about ourselves. Whilst they may disagree on the exact nature of self-concept, the terminology or process, they all agree on “how dependent this knowledge is upon what other people tell us about ourselves” (Fontana, 1995: p263), both directly and indirectly. They also agree that failure to achieve goals or overcome challenges, or a discrepancy between our ‘ideal-self’ and reality can cause low self-esteem (Fontana, 1995; 1977; Smith & Cowie, 1991). Lawrence defines self-esteem as “the individual’s evaluation between self-image and ideal self” (ibid: p103), whilst Fontana describes it as “concerned with the value we place upon ourselves; of all areas of self-concept it is one of the most important” (1995: p262). Coopersmith (1968, cited in Fontana, 1995) and Bee (1989, cited in Fontana, 1995) suggested that children with high self-esteem performed better academically than children with low self-esteem. They set themselves higher goals, were less deterred by failure and were realistic about their own abilities. They also tended to participate in activities more, were able to express feelings and emotions and deal with criticism. Children with low self-esteem on the other hand, tended to play safe by setting easily achievable goals, were easily upset by criticism and were anxious for approval (Coopersmith, 1968; Bee, 1989, ibid). This suggests that a knowledge of self-concept development is important for teachers, not only because it can help them better understand the children they are teaching, but because it can give them “some practical guidance on how they can best influence [their] development for good” (Fontana, 1995: p265). The development of self-concept and high self-esteem are seen as essential for learning (Huitt, 2004) and this idea is 7 reflected in both the National Curriculum for England (DfEE, 1999) and the Every Child Matters agenda (DfES, 2005). As Canfield & Wells point out, “research literature is filled with reports indicating that cognitive learning increases when selfconcept increases” (1976: p7). Lawrence argues, “for the child of school age […] self-esteem continues to be affected mainly by the significant people in the life of the student, usually parents, teachers and peers” (ibid: p104). Consequently, teachers, like parents, need to provide a positive environment for the children in their care, suggesting that teachers should listen to and value the children in their class, consider them capable of doing the work set, be consistent, set realistic targets, give encouragement and provide opportunities for them to take responsibility and be independent (Fontana, 1995; Canfield & Wells, 1976). The relationship between the child and teacher, however important, is not the only influence on a child’s selfesteem at school. Their home environment, including their relationship with parents, their socio-economic background, gender, physical development, and peer relationships are significant influences on self-esteem (Fontana, 1995; Mussen et al, 1984). The school in which the author teaches is in a socially deprived part of Reading. Research suggests that children from poor socio-economic backgrounds generally have a lower self-esteem than children from environments higher on the socio-economic scale (Fontana, 1995; Mussen et al, 1984). Fontana argues that this is not surprising because they “have constant reminders of their supposed ‘inferiority’ in the form of dilapidated environments, limited facilities [and] older school buildings” (1995: p266). The author’s class of 28 children has an equal split of boys and girls. Fontana (1995) argues that girls generally have lower self-esteem than boys and points to evidence that showed girls deliberately depressed their performances in problem solving tasks when paired with boys. This, Fontana (1995) suggests, is due to cultural factors such as the status of women in society. This does not seem to be 8 true of the author’s class where the girls are generally much more self-assured and able to work effectively with whoever they are paired. It is the boys that often refuse to work with the girls, try to avoid answering questions and distract others. Kindlon and Thompson (2000) support this view, arguing that the Primary School is largely a female environment where a boy’s more physical response to things, particularly when their feelings outstrip their language skills, is often seen as bad behaviour. Where the girls seem to be less assured than the boys is in their peer relationships, which is a key area of self-concept development (Keenan, 2002; Thompson & O’Neill, 2001). The girls’ friendship groups change regularly, with ‘in’ crowds and interests changing almost daily. It is also noticeable how unpleasant girls can be to each other through social exclusion and name-calling. The boys, by contrast, seem to have a fairly set ‘group’ that is based around playground football. Arguments and ‘fallings out’ are usually short lived, although they sometimes involve physical violence. This would seem to suggest that for girls in Primary School, friendships have a significant effect on self-esteem. As Simmons puts it, “your friends know you and how to hurt you. They know what your real weaknesses are. They know exactly what to do to destroy someone’s self worth” (2002: p43). Peer relationships within the class and ‘social status’ also seem to be affected by physical development. This view is supported by Thompson & O’Neill (2001) who argue that boys who mature early are more likely to be athletes and school leaders, with associated high selfesteem whereas girls who physically mature early are more likely to be teased and have lower self-esteem. Children, it seems, face twin challenges at primary school – “academic competency and adequacy in social relationships” (Burns, 1982: p3) - and this is reflected in Erikson’s 4th Stage of Development: Industry vs. Inferiority (Burns, ibid). It is against this background that teachers try to help children form positive concepts about school and enhance the children’s self-esteem, with the hope that it 9 will also improve their learning. The author tries to employ what Smith & Cowie (1991) describe as a ‘democratic’ teaching style. This style of teaching is characterised by clear aims and objectives, which are discussed with the children, the involvement of the class in decision-making, choice and a high level of involvement in tasks. The teacher acts as a facilitator of discussion rather than the director (Smith & Cowie, 1991). Research by Lewin et al (1939, cited in Smith & Cowie, 1991) suggested that this style of teaching could produce high levels of satisfaction and motivation within the class and less hostility between the children. Although productivity was often lower than with a more authoritarian teaching style, the quality of work was better. However, as Bennet (1976, cited in Smith & Cowie, 1991) points out, it is essential for the teacher to give direction and support because insecure children found it harder to cope academically with the emphasis on selfdirected learning and autonomy. A ‘democratic’ teaching style, where children have control over their environment and the work they are doing is relevant to them, can help to give children positive experiences of school, which could also improve their own self-concepts (Fontana, 1995). Perhaps more important than the teaching style is the way in which the teacher interacts with children or the child-teacher relationship. Baker-Lunn (1970, cited in Smith & Cowie, 1991) and Ferri (1972, cited in Smith & Cowie, 1991) found a strong relationship between self-concept, teacher judgements and low self-esteem. The author tries to value children by knowing something about them (e.g. their hobby), by listening to them, by being honest with them, and by being consistent and fair, particularly when dealing with bad behaviour. The author also tries to have a ‘can do’ attitude towards both behaviour and academic work, believing that the children will be successful in what they are doing. In reality, it is not always possible to act this way all the time. Time constraints, the number of children and a long, tiring week sometimes mean that teachers do not live up to the ideals. However, doing so can make a difference to a child’s self-esteem. If a teacher believes in a child, they are more likely to behave like a successful pupil, 10 but children that are judged unfavourably are more likely to have a low opinion of their ability and misbehave (Smith & Cowie, 1991). However, as Fontana (1995) argues, teachers should not over exaggerate a child’s abilities or give false praise. Nor should they avoid criticising or challenging a child. Instead, teachers should do things in such a way that self-concept and self-esteem is protected (Fontana, 1995). The author’s class is the most able in terms of literacy ability. Within the class itself, the children are grouped, in line with the school’s policy, for Literacy and Numeracy. For all other lessons, the children work in mixed ability groups, either across the class or across the year group. Despite the author’s attempts to obscure the ability groupings within the class with neutral names and the teaching staff not using terms such as ‘top group’, the children quickly understood where they were, academically, both within the year group and the class. Hargreaves (1967, cited in Fontana, 1977) and Lacey (1970, cited in Fontana, 1977) argue that grouping makes a difference to self-concept because being in the ‘top group’ is seen as being accepted by the school, whereas being in the ‘bottom group’ is seen as being rejected by it. If children are to be separated by ability, Fontana argues, it “should be done in a way which protects the self-esteem of the less able as well as of the more able” (1977: p42). This view is particularly important, as some of the children in the school seem to deal with their status as ‘bottom group’ or ‘not academic’ by developing an alternative set of values that stress aggressiveness or ‘acting up’. In some cases more academic children are teased and called names for being successful in school. Canfield & Wells (1976) suggest that children do this not only to avoid failure, but also to be ‘successful’ in their own terms. In other words they will, like Rogers suggests, distort their experiences to ensure that it is consistent with their self-concept (Burns, 1982). It is also the group of children in the middle – those that identify with neither group – that can suffer. As the teacher deals with the high 11 achievers and manages the behaviour of others, these children can often be withdrawn and overlooked (Smith & Cowie, 1991). Another way in which the teacher can help children build their self-concept and enhance their self-esteem is by providing opportunities for them to experience success (Fontana, 1995; Burns, 1982). The author does this through differentiated and achievable tasks, questioning and by providing additional support. As Canfield & Wells suggest, in any potential learning situation, the student is risking “error, judgement, disapproval, censure, rejection, and […] even punishment” (1976: p7). If they are successful they are likely to take a risk again, if they are unsuccessful, they are likely to be reluctant to try in the future. A good example is Numeracy. In the author’s class, the children are encouraged to have a go at the work on whiteboards before committing it to paper. This allows them to try things out, make mistakes and ask for help with the knowledge that the work won’t be marked. Through PSHE lessons, the author tries to provide opportunities for the children to express their feelings about their work, about the class environment and to improve social skills. There is an emphasis on positive reinforcement, where each child’s strengths are celebrated. This is underpinned by a ‘Star of the Week’ system where children are asked to catch one of their number doing something positive and to record it on the board, ‘sticker’ reward systems and celebrations of children’s work on display boards and at ‘sharing assemblies’. Children are praised publicly, but disciplined privately. The school’s behaviour management policy calls for the teacher to find ways for a child to ‘save face’ and to be part of the solution to any problems. The promotion of a positive environment where we can feel good about each other and ourselves is a key aim. There are some criticisms to this approach, however. Mussen et al question its academic purpose, arguing that “simply teaching [children] to feel good about themselves might reduce some anxiety about failure […] but it is 12 not a very powerful way to change the academic performance” (1984: p358), whilst Burns points out that “there is no action that a teacher can take that a child with a negative self concept cannot interpret in a negative way” (1982: p14). Although the author recognises that some children do seem to disbelieve anything positive said to them, the purpose of PSHE is to help such children develop an ‘emotional intelligence’ that would allow them to look more positively at themselves, a view shared by Daniel Goleman (1996). And surely, creating a positive environment is preferable to the alternative. The development of self-concept and the building of self-esteem are considered to be essential to academic success (Fontana, 1995). Consequently, the understanding of self-concept development and its relationship with self-esteem is essential for teachers “to understand children, help some maintain and enhance positive views about themselves, and help others to change their views” (Burns, 1982: p31). The work of James, Cooley, Mead, Erikson, Rogers and Kelly has established that the feedback we get about ourselves directly and indirectly from others, failure to achieve goals or overcome challenges are the key influences on self-concept development (Fontana, 1995). Influences on self-esteem include socioeconomic background, gender, physical development and perhaps most importantly, the relationships we have with significant others (Mussen et al, 1984). It is against this background that teachers try to create an environment and to provide experiences that help children build positive concepts about school, learning and themselves; a task that Weare (2004) recognises is not an easy task. [4,367 Words] 13 Bibliography Burns, R (1982) Self-Concept Development and Education, pp441 London: Holt Canfield, J & H Wells (1976) 100 Ways to Enhance Self-Concept in the Classroom: A Handbook for Teachers and Parents, pp253 London: Prentice Hall Crain, W (1992) Theories of Development: Concepts and Applications, 3rd Edition, pp368 Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Department for Education and Skills (DfES) (2005) Every Child Matters Online at: http://www.everychildmatters.gov.uk/ [25.8.05] Department for Education & Employment (DfEE) (1999) National Curriculum 2000 for England Online at www.nc.uk.net [24.8.05] London: HMSO Fontana, (1995) Psychology for Teachers, 3rd Edition, pp406 Basingstoke: Macmillan Fontana, D (1977) Personality and Education, pp178 London: Open Books Huitt, W. (2004) Self-concept and self-esteem. Educational Psychology Interactive. On line at: http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/col/regsys/self.html. [25.8.05] Goleman, D (1996) Emotional Intelligence, pp367 London: Bloomsbury James, W (1890) The Principles of Psychology, On line at: http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/Principles/ [25.8.05] New York, NY: Dover Keenan, T (2002) An Introduction to Child Development, pp288 London: Sage Kindlon, D & M Thompson (2000) Raising Cain: Protecting the Emotional Life of Boys, pp298 New York, NY: Ballantine Books Mead, G (1913) The Social Self, Journal of Philosophy, Psychology, and Scientific Methods, 10, 374-380, On line at: http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Mead/socialself.htm [25.8.05] 14 Mosley, J (1993) Turn your school around: A Circle Time approach to the development of self-esteem and positive behaviour in the primary staff room, classroom and playground, pp183 Cambridge: LDA Mussen, P et al (1984) Child Development and Personality, 6th Edition, pp590 New York: Harper Pollard, A & A Filer (1996) The Social World of Children’s Learning: Case Studies of Pupils from 4 to 7, pp328 London: Cassell Pollard, A (2002) Readings for Reflective Teaching, pp384 London: Continuum Pollard, A (2005) Reflective Teaching Website Online at http://www.rtweb.info/index.html [24.8.05] Purkey, W. (1988). An overview of self-concept theory for counselors. ERIC Clearinghouse on Counselling and Personnel Services, (An ERIC/CAPS Digest: ED304630) On line at: http://www.ericdigests.org/pre-9211/self.htm [25.8.05] Simmons, R (2002) Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls, pp301 London: Harcourt Smith, P & H Cowie (1991) Understanding Children’s Development, 2nd Edition, pp488 Oxford: Basil Blackwell Thompson, M & C O’Neill Grace (2001) Best Friends, Worst Enemies: Understanding the Social Lives of Children, pp299 New York, NY: Ballantine Books Weare, K (2004) Developing the Emotionally Literate School, pp222 London: Paul Chapman 15