Editorial - University of Florida

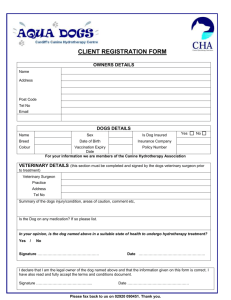

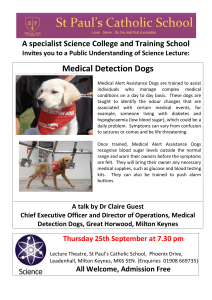

advertisement

Editorial Special Issue: Canine Behaviour and Cognition Clive D. L. Wynne, University of Florida Address for correspondence: Clive Wynne Department of Psychology University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32611, Ph: 352/273-2175 Fx: 352/392-7985 Email: wynne@ufl.edu or clivewynne@gmail.com Wynne Editorial 1 Editorial Special Issue: Canine Behaviour and Cognition Dogs were among the very first animals to enter the psychologist’s laboratory when Pavlov discovered the form of conditioning that now carries his name in the 1880s (Pavlov, 1927). Pavlov’s own experimental paradigm never inspired large numbers of followers, however, because the assessment of salivary conditioning required a delicate operation to insert a cannula into the dog’s mouth to capture and measure the production of saliva (Goodwin, 2008). Over the years, dogs had an occasional presence in the psychological laboratory, but their use as subjects gradually waned, until, by the 1980s, the psychological literature was down to fewer than ten papers on dogs each year. Furthermore, as Miklósi (2008) outlines, notwithstanding Konrad Lorenz's enthusiasm for them (Lorenz, 1954), ethologists also generally ignored dogs because they were not real "wild" animals. Suddenly, in the late 1990s, something changed – and changed quite dramatically. Starting with the groundbreaking work of Vilmos Csányi, Ádám Miklósi, and Jozsef Topal and the team that they built around them at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary and matched quickly by the work of Brian Hare and his research group at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, interest in the behaviour of dogs and their closest relatives has grown at a phenomenal pace over the last decade. In 2008, over 70 papers on dog behaviour were published in the Wynne Editorial 2 psychological literature, and there is every indication that the number of papers on dogs is continuing to grow. There are so many excellent reasons to study dog behaviour that it is hard to understand why dogs were ignored for so long. Dogs live in intimate proximity to humans. In the United States, 40% of households include a dog, and 40% of dog owners allow their dogs to sleep on their beds (American Pet Products Manufacturers Association, 2008; American Veterinary Medicine Association, 2007). There are few members of our own species with whom we share such an intimate relationship as with our dogs. People typically refer to dogs as family members (Kubinyi et al., this issue). As well as bringing great pleasure, dogs are also a significant source of pain and distress to humans. Again considering just the United States, dogs bite around 4.7 million people per year (Center for Disease Control, 2003): by the age of 12 a child has a 50% chance of having been bitten by a dog (Gershman & Sacks, 1994). Dogs are also big business. In 2007, pets were estimated to be a $40 billion industry in the USA, with dogs responsible for the largest share of that expense (American Pet Products Manufacturers Association, 2008). Dog behaviour – or rather misbehaviour – is a major preventable cause of pet dog mortality. Every year, around two million dogs are destroyed in shelters (Patronek and Glickman, 1994 – other estimates are as high as nine million Nasser, Talboy and Moulton, 1992). Dogs ends their days euthanized in a shelter facility because they have failed as a family pet. And this is usually due to a problem with behaviour. Wynne Editorial 3 These urgent societal concerns might create a duty on behavioral scientists to take an interest in dogs, but in themselves they would not ensure that the task would be an interesting one. It quickly became clear in the early work from the Budapest and Leipzig groups, however, that there was something quite remarkable about dogs. Dogs have been shown to have an exceptional sensitivity to human actions and intentions. First it was shown that dogs follow a human pointing gesture to locate hidden food (Miklósi, Polgardi, Topál, & Csanyi, 1998); subsequently dogs have been shown to attend to whether a human can see them or not in choosing whether to follow a human command (Brauer, Call & Tomasello, 2004; Call, Brauer, Kaminski, & Tomasello, 2003), and in selecting which of two humans to beg from (Cooper et al., 2003; Gacsi, Miklósi, Varga, Topál, & Csanyi, 2004). A dog has been found with a vocabulary of several hundred item labels to which it can add new names very rapidly (Kaminski, Call, & Fischer, 2004). Dogs may also imitate humans and other dogs under certain conditions (Range, Viranyi & Huber, 2004; Miller RayburnReeves & Zentall, 2009). This suite of skills exceeds even what has been found in humans’ closest relative, the chimpanzee, and entitles us to call the dog the "Poor Man's Chimpanzee," when it comes to the study of complex human-like socialcognitive abilities (Bloom, 2004). And, unlike the chimpanzee or many other animal species, dogs are available to behavioral scientists at little or no expense. These remarkable cognitive abilities are only one reason why behavioral scientists are excited about dogs and other canids. This special issue of Behavioural Processes highlights several others. Wynne Editorial 4 The present issue includes two papers on the vocalizations of canids. Kathryn Lord and colleagues from the University of Massachusetts provide a provocative analysis of barking in dogs and other animals. They argue that barking is a call that invites individuals to mob a predator. Dogs bark more than other canids because dogs more often find themselves in situations where escape from a threat is not an option and thus they call for support more often. Svetlana Gogoleva and colleagues at Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow Zoo, and the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences investigate vocalizations made by individuals from a unique colony of silver foxes (Vulpes vulpes) bred for over forty years for tame behaviour. Gogoleva et al. compare the vocalizations from different crosses of tame and wild-type foxes. They find that the artificial domestication carried out on these foxes has led to characteristic differences in the types of vocalizations made by the animals. These differences in vocalizations are present in the different crosses of tame and wild animals in ways which indicate that these calls are distinct phenotypical traits in the foxes. Keven Kerswell and colleagues at Monash University in Sydney, Australia, focus on another aspect of social signalling between canids. They analyze the behaviour of 40 litters of pups from 32 different breeds of dog and compare the frequency with which these pups produce different forms of social signal such as waggling their ears or wagging their tails. These frequencies of social signal are considered in relationship to the adult morphology of the particular breed of dog. Their extensive analysis did not uncover any relationship between adult morphology and social signalling of different types in the pups, suggesting that there has been no loss of Wynne Editorial 5 communicative behaviors due to the development of diverse morphologies of different dog breeds. Two papers in this special issue look directly at the nature of the relationship between human and pet dog. Kurt Kotrschal and colleagues at the Konrad Lorenz Research Station and the University of Vienna in Austria investigated the interrelationships between owner personality, dog personality, and the effectiveness of the human-animal bond. Human and dog personalities were assessed with standard tests, and the effectiveness of the relationship between pet dog and owner was ascertained from video analysis of the human and dog interacting in a number of situations. It was found that more extroverted owners appreciated shared activities with their dogs more, while more neurotic owners were more likely to view their dogs as sources of social support and spent more time with them. Dogs with female owners were more sociable than dogs with male owners. Enikö Kubinyi and colleagues at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest also looked at the relationship between dog personality traits and dog and owner demographic factors. Kubinyi et al.’s study is remarkable for the very large sample (over 14,000 individuals) they were able to find by using a commercial magazine linked to a web page to invite and record the responses of participants. The authors found that calm dogs were older and less likely to be neutered. Trainability was mainly influenced by the number of training experiences the dog had already had. Younger dogs were more sociable and bolder than older ones. This study shows the promise of the web as a means of collecting data on human-domestic animal relationships. Wynne Editorial 6 Angel Elgier and coworkers at the Universidad de Buenos Aires in Argentina also investigated communication between pet dog and humans. In their case they focussed on situations where a human indicates to a dog which of two containers hides food by making a pointing gesture with his arm. They compared dogs’ willingness to follow a point to situations where a colour cue indicates the container with the hidden food. They found that dogs would readily give up their spontaneous tendency to follow the human pointing gesture if they were trained to follow the colour cue. These results indicate the ease with which dogs can be trained to follow new cues in a communicative situation. Nicole Dorey and collaborators at the University of Florida are also interested in situations in which a pet dog is guided towards hidden food by a human pointing gesture. They performed a meta-analysis of 14 studies in the literature that have investigated dogs' abilities on this task with a view to uncovering performance differences between dog breeds. No differences between breeds or even groups of breeds were found, but they are reluctant to conclude that this absence of evidence is evidence of absence. Rather they note that the range of breeds of dog that have been tested remains very small, notwithstanding the large number of individuals that have been tested across these 14 studies. They argue that additional experiments are required that target specific breeds that are likely to be particularly successful or unsuccessful on the task, and make some suggestions for how such predictions could be generated. Wynne Editorial 7 An interest in the impacts of training on a dog’s behaviour is also evident in the contribution from Sarah Marshall Pescini and colleagues at the University of Milan in Italy. They compared the performance of dogs with extensive histories on two different forms of training (agility and search and rescue), with that of untrained pet dogs on solvable and unsolvable problems. They found that the different dogs’ problem solving behaviour was similar on both problems, but the groups of dogs differed in how they responded to their owners while attempting the problems. In the solvable task, the trained search and rescue dogs looked back towards their owner less often than did the agility-trained dogs, and the agility dogs looked back and forth between the apparatus and their owner more often than did the pet dogs. On the unsolvable test the agility dogs looked at their owner longer than did the other two groups, and the search and rescue dogs barked more than the other dog groups. Victoria Wobber and Brian Hare from Harvard University compared the performance of the “poor man’s chimpanzee” to that of real chimpanzees. Dogs and chimps were tested on two versions of a simple task. In one version each animal was given a choice between two people, one of whom gave a piece of food if selected; in the other version each animal had a choice of two different-coloured containers, one of which contained hidden food. Once each animal had mastered each version of the task, the rewarded person or container was swapped over, so that food was now obtainable from the previously unrewarding person or container. Wobber and Hare found that dogs attained similar levels of performance on both versions of the task, whereas chimpanzees performed better when the food was offered by humans than Wynne Editorial 8 when it was hidden in inanimate containers. When the rewarded individual or object was reversed, dogs relearnt both versions of the task at a similar rate, whereas chimpanzees relearnt the version of the task with humans more rapidly than the inanimate version. The authors conclude that this pattern of results implies that the sophisticated social skills of dogs are a highly specialized product of domestication. Two papers in this collection look at dogs’ abilities to reason about the physical world. Sylvain Fiset from the Université de Moncton in Edmunston, Canada, reports on how dogs locate hidden objects by the use of landmarks. Dogs were trained to find a ball located equidistant from a landmark and a wall, or, in a second experiment, from two walls. On tests the landmark’s position was shifted. The results show that the dog’s search behaviour was predominantly controlled by averaging the distances from the walls and the landmark, in a manner consistent with current theories of animal navigation. Holly Miller and collaborators at the University of Kentucky investigated dogs’ understanding of the hidden movement of an object. Prior studies had suggested that dogs could locate objects that moved when hidden inside a container such as a bucket, but only if their gaze was drawn to the container and they continued to track it with their eyes as the object and container were shifted. Miller et al. tested whether any dogs could follow a hidden object as it moved without tracking it with their gaze. They achieved this by interposing delays during which the dog could not see the experimental objects after the object in its container was moved and before Wynne Editorial 9 the dog was released to search for the object. Although some dogs had great difficulty finding the hidden object after a delay, others were unaffected, suggesting that these dogs showed a deeper appreciation of the implications of hidden movement. Finally, one of the most intriguing papers in this issue looks directly at owner perceptions of their dog’s behaviour. Alexandra Horowitz, from Barnard College in New York, investigates the “guilty look” in dogs. What dog owner has not come home to a very guilty looking dog and uncovered some kind of damage in the house…? Horowitz asked owners to order their dogs not to eat a tasty treat and then to leave the room. While the owner was away, Horowitz gave some of the dogs this forbidden treat before asking the owners back into the room. Some of the owners were told that their dog had eaten the forbidden treat, others were told their dog had behaved properly and left the treat alone. What the owners were told however had no correlation with reality. Analysis of the dogs’ behaviour showed that it had nothing to do with whether they had actually eaten the forbidden treat or not. Dogs looked “guilty” if they were admonished by their owners. In fact, dogs that had been obedient and had not eaten the treat, but were scolded by their (misinformed) owners, looked more “guilty” than those that had in fact eaten the treat. Thus the dog’s guilty look is a response to the owner’s behaviour, and not indicative of any appreciation of its own misdeeds. The twelve papers in this issue give an rich impression of the vitality and diversity of this field of behavioural science. That this is not a new field is obvious to anyone Wynne Editorial 10 who has heard of Ivan Pavlov, but the energy in the field is certainly a new phenomenon. The low costs of entry are likely to ensure rapid future growth to the area in the coming years. In this issue, we see contributions from eight countries across four continents – a quite remarkable degree of diversity. Before concluding that all is well in the state of canine behavioural research, however, I feel compelled to mention a worrying trend that was made clear to me as one of the co-authors of the contribution by Dorey et al. in this issue. In our attempt to carry out a thorough and effective meta-analysis we asked the authors of the 14 papers we analyzed to provide us with their raw data. To our considerable surprise, the majority of authors refused to cooperate. By the today’s standards these are tiny databases, easily exchanged through email, so no practical barrier stood in the way of sharing them. The sharing of raw data is a principle enshrined by research funding organizations around the world, including the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health in the United States, the Deutscheforschungsgemeinschaft in Germany, and many others. It is also a condition of publication in the majority of scientific journals, including Nature, Science, all the journals published by the American Psychological Association, as well as this journal. Nonetheless, the authors declined repeated requests for data. This failure to share impedes the progress of the field because it makes it impossible to draw additional conclusions from data sets that have already been collected. It also raises ethical issues because it leads to needless repetition of animal studies that have already been carried out. It is a sad comment on an otherwise vibrant, truly international, and intellectually diverse field of research. Wynne Editorial 11 Dogs are not just objects of scientific study, but they also have a rich existence in the human imagination. Artworks representing dogs date back many thousands of years, and if they are not among the earliest human depictions of animals that is only because humans were creating art before dogs even existed (Delporte, 1990). In that spirit, and as far as I know in a first for a scientific journal, the online accompanying material for this editorial consists of a musical composition by Chester Udell entitled “Vocalizations”. This work was created out of sounds collected at Wolf Park, Battle Ground, Indiana. But it is not simply a sound collage. Rather, the composer has manipulated the sounds of wolves and other animals together with other ambient sound at that location into a strangely moving work of art. I trust it will inspire researchers to continue the investigation of canine behaviour and cognition. Acknowledgements I thank the authors of all contributions for their timely work in providing the papers that make up this special issue, and in their constructive responses to criticism. I thank the many anonymous reviewers whose efforts helped strengthen the issue. My thanks to Monique Udell for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this editorial. Wynne Editorial 12 References: American Pet Products Manufacturers Association (2007). 2007 National Pet Owners Survey, http://www.appma.org/press_industrytrends.asp. Retrieved Aug 10, 2008. American Veterinary Medicine Association. (2007). U.S. Pet Ownership & Demographics Sourcebook. Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medicine Association. Bloom, P. (2004). Can a Dog Learn a Word? Science, 304, 1605-1606. Brauer, J., Call, J., and Tomasello, M. (2004). Visual perspective taking in dogs (Canis familiaris) in the presence of barriers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 88: 299-317. Call, J., Brauer, J., Kaminski, J., and Tomasello, M. (2003). Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) are sensitive to the attentional states of humans. J. Comp. Psychol., 117: 257-263. Center for Disease Control, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 52: 605-610. (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5226a1.htm 2003). Cooper, J. J., Ashton, C., Bishop, S., West, R., Mills, D. S., and Young, R. J. (2003). Clever hounds: social cognition in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 81: 229-244. Delporte, H. (1990). L'image des animaux dans l'art prehistorique. Paris, France: Picard Editeur. Wynne Editorial 13 Gacsi, M., Miklosi, A., Varga, O., Topal, J., and Csanyi, V. (2004). Are readers of our face readers of our minds? Dogs (Canis familiaris) show situation-dependent recognition of human's attention. Anim. Cogn., 7: 144-153. Gershman, K. A., and Sacks, J. J. (1994). Which dogs bite? A case-control study of risk factors. Pediatrics, 93: 913. Goodwin, C. J. (2008). A History of Modern Psychology (3rd ed.). Wiley, New York. Kaminski, J., Call, J., and Fischer, J. (2004). Word Learning in a Domestic Dog: Evidence for "Fast Mapping". Science, 5677: 1682-1683. Lorenz, K. (1954). Man Meets Dog. Routledge. New York. Miklosi, A. (2008). Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Oxford University Press, New York. Miklósi, Á., Polgárdi, R., Topál, J. and Csányi, V. (1998). Use of experimenter-given cues in dogs. Anim. Cogn., 1: 113-121. Miller, H. C., Rayburn-Reeves, R., and Zentall, T. R. (2009). Imitation and emulation by dogs using a bidirectional control procedure. Behav. Proc., 80: 109-14. R. Nasser, J. Talboy and C. Moulton, (1992). Animal Shelter Reporting Study, 1990, American Humane Association, Englewood, CO G. Patronek and L. Glickman, (1994). Development of a model for estimating the size and dynamics of the pet dog population, Anthrozoos, 7: 25–41. Wynne Editorial 14 Pavlov, I. (1927). Conditioned reflexes. Oxford University Press. London Range, F., Viranyi, Z., and Huber, L. (2007). Selective imitation in domestic dogs. Curr. Biol., 17: 868-872. Wynne Editorial 15