How long have Native Americans lived in Panama? The American

advertisement

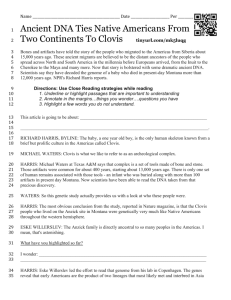

How long have Native Americans lived in Panama? The American continent was the last to be colonized by human beings no more than 20,000 and no less than 15,000 years ago (calibrated dates are used). All lines of evidence lead to Northeast Asia as the ancestral homeland and point of departure for the first colonizers, whose descendants had reached southern South America by 14,500 years ago. The hypothesis that there was a single initial migration is becoming increasingly robust. If there were multiple migration events these would have represented a genetically uniform population originating in the same area. Geneticists are increasingly accepting the idea that all the surviving Native American groups in Central and South America descend from the small population that participated in the initial movements, which most likely took a Pacific coastal route towards the south. They appear to have progressed fast. Tom Dillehay’s ground-breaking excavation at Monte Verde, in the south of Chile, uncovered a 14,500-year old settlement of huts made of wood and animal skins whose occupants hunted mastodon (Cuvieronius) and an extinct camel-like species (Paleolama), gathered wild potatoes, and used seaweeds obtained from the distant coast for food and medicines. They had been in the area long enough to develop a life style well adapted to local landscapes and resources. If some human groups were established in southern Chile by 14,500 years ago, where is the evidence for their passage through Panama? It is extremely tenuous consisting of two fragments of possible stone projectile points of the “Jobo” variety, which was used at Monte Verde and Venezuelan sites, such as the Taima-Taima megafauna kill-site. Both the Panamanian examples were found on the surface. Their contemporaneity with the two South American sites is based on technical and stylistic similarities alone. Other lines of evidence give credence to the very low “visibility” of humans at this time in Panama -- at least in regions that have been explored in some detail. Dolores Piperno and her colleagues did not detect a human presence in the sediments of Lake La Yeguada (Veraguas, 650 m) between 18,000 and 13,200 years ago. At the latter date human forest clearance and burning began in earnest, probably perpetrated by “Clovis” peoples whom we mention again below. Although the Cueva de los Vampiros (Coclé) was available as a camp site 18,000 years ago, it was apparently not visited by humans until at least 13,200 years ago. Archaeologists offer two explanations for the extreme rarity of sites like Monte Verde and Taima-Taima. If the initial human migration along the Pacific side of the isthmus indeed hugged the coast, camps would have been drowned by rising sea levels triggered by global deglaciation. It is also likely that, at this time, the climate, terrestrial landscape and coastal habitats of Pacific Panama were far from optimal for groups of hunters and gatherers. Vegetation history models indicate it probably rained 30% less that today. Estuaries and mangroves as extensive as the ones exist today doubtfully existed 14,500 years ago. One of the purported fragments of a “Jobo” point was gathered on the eroded shore of Lake Alajuela in the Caribbean basin of the Chagres River. One can only speculate that the narrowness and low relief of the central portion of the isthmus, in addition to the presence there of areas with little arboreal vegetation, stimulated the dispersal of some immigrants towards the Caribbean whence they continued moving until they found especially favorable habitats in northern Venezuela Venezuela. Between about 13,500 and 13,000 years ago, evidence for a human presence on the isthmus becomes suddenly more definitive and ubiquitous. In several areas, stone tools used by hunters and gatherers known as “Paleoindians” are found. These tools differ in important aspects from those employed by the occupants of Taima-Taima and Monte Verde. The most “iconic” artifact is a stone projectile point labeled “fluted” because one or two channel-like flakes were detached from the base making it easier to lash the point with cord or sinews to a wooden lance that customarily used a fore-shaft made -- in North America at least -- of pieces of proboscidean tusks. Wood or bone spear-throwers or “atlatls” increased the thrust and penetrating power of “Clovis” spears. Many specialists propose that this new technological tradition, whose first manifestation ca. 13,200 years ago is known as “Clovis”, developed initially in the United States whence it moved rapidly southwards as far as northern Venezuela. The widespread “Clovis” tool kit of spears, spear-throwers, skin and wood scrapers, knives and perforators undoubtedly improved humans’ ability to kill, butcher and skin large animals. “Clovis” deposits that are buried and thus appropriate for radiocarbon dating have so far eluded archaeologists in Costa Rica and Panama. Even so, the similarities among some “Clovis” sites in the southern U.S. and others located in Pacific Panama and Costa Rica (Turrialba, central Caribbean) are so striking that it is logical to assume that they were broadly coeval reflecting a rapid movement of the tradition from North to South. Two workshops where stone tools of the “Clovis” tradition were made have been studied in Panama. La Mula-Oeste, in the Sarigua saltflat (Herrera), is the most informative. According to Tony Ranere’s technological study, making fluted points was the primary activity here. Knappers took advantage of local outcrops of veins of milky agate. Not only the projectile points, but also a spurred end-scraper, perforators, burins and blades all bear the hallmarks of the Clovis tradition. The “Clovis” tools could not be located in an intact soil. It is intriguing, nonetheless, that that in the sixties, Don Crusoe -- then researcher at Florida State University -- picked up a charcoal sample from a hearth in the Sarigua albina, It returned a date of about 13,200 years. Since this locality’s geographical coordinates were never divulged, it is not possible to determine how close it was to the La Mula-Oeste workshop. This date, however, is consonant with the hypothesis proposed by Tony Ranere and Georges Pearson that, from a technological point of view, both La Mula-Oeste and Sitio Nieto represent the beginnings of the “Clovis” tradition. The only Panamanian site, at which fluted points and other Paleoindian artifacts have been found in buried deposits, is the Cueva de los Vampiros, Coclé. These materials lay on top of a soil rich in organic matter that was interpreted by Georges Pearson as the first evidence for human occupation in this site, about 13,500 years ago. They are stratified underneath another 14C date of 11,200 years – a very broad temporal range that impedes the accurate contextualization of the artifacts. Two fragments of fluted points were recovered. One belongs to the “Fish-Tail” variety, widely distributed from southern Mexico to Patagonia. The other point could be a late “Clovis” example, which broke. Other tools typical of the Paleoindian era were also found: a scraper with a lateral spur, end-scrapers on blades, and small “thumb-nail” scrapers. Pearson proposed that Cueva de los Vampiros was used sporadically by Paleoindians as a camp site where tools were curated and animal skins and perhaps wooden artifacts were prepared. The stone tool assemblage infers these activities. However, bones were not recovered in these strata. This is a depressing fact since it has not yet been confirmed whether the species of large extinct animals that were exploited by Paleoindians in South America, such as mastodons, giant ground sloths and giant turtles, were also hunted by Panamanian Paleoindians. To sum up, it is likely that the first humans arrived on the isthmus about 15,000 years ago. They may have been so few that they hardly left any evidence. They may also have frequented mostly the Pacific coastal lowlands in areas now flooded by the post-glacial sea. The “visibility” of archaeological sites in Panama improves greatly 13,500-13,000 years ago when hunter-gatherers of the “Clovis” tradition were established in the central Pacific and central Caribbean. It is generally supposed they came to Panama from the north. From this moment on, humans lived continuously in some areas of Panamá. The Cueva de los Vampiros and other rock-shelters in Veraguas, Chiriquí and Coclé continued to act as dwellings for thousands of years after the demise of the Paleoindian technology at ca. 11,500 years when modern climatic conditions were setting in. Following the initial human colonization of the Lake La Yeguada basin 13,200 years ago, forest clearance and the spread of second growth vegetation continued and intensified. The native peoples of the isthmus altered their lifestyles in the face of post-glacial environmental change. Plant cultivation and intensive tree product harvesting gradually became primary subsistence endeavors. By 8000-6000 years ago the appearance of non-isthmian cultivated plants such as maize, manioc and squash, acted in tandem with increasing coastal resource use and ever larger populations to foster slash-and-burn agriculture and the spread of native communities across the isthmus. The numerous Native American groups that the Spanish encountered and decimated a little more than 500 years ago were in large part the descendants of the first human groups that arrived on the isthmus between 15,2000 and 12,500 years ago. New evidence about the genetic history of the native populations of America appears regularly in specialized scientific literature. The Italian geneticists Ugo Perego and Alessandro Achilli, in conjunction with the Gorgas Memorial Laboratory, sampled about 1500 Panamanians with a view to tracing the genetic contribution of Native Americans, Africans, Asiatics and Europeans. Contrary to what most Panamanians believe, the genetic heritage of the modern population is overwhelmingly Native American, at least on the maternal side. According to analyses of mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited maternally, about 80% of the modern Panamanian population descends from a Native American woman. Fifty percent of Panamanians belong to a single mitochondrial haplogroup (A2) whose antiquity is estimated to be more than 10,000 years. Genetic evidence also shows that the majority of present-day Native American peoples of Panama are likely to descend from earlier populations who have resided in or near Panama for 12,500 years, and perhaps 15,000 o even 17,000 years. These results are broadly compatible with the archaeological and paleoecological data we have summarized, and receive considerable support from historical linguistic studies.