Backyard Field Trips: Bringing Earth Science to Life

advertisement

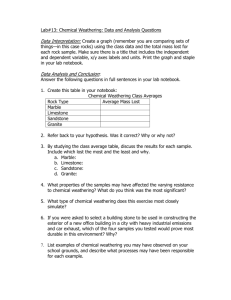

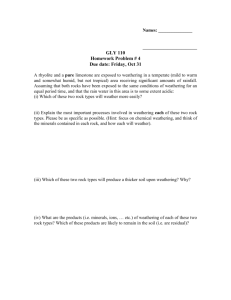

Backyard Field Trips: Bringing Earth Science to Life on Campus Purpose: The purpose of this backyard field trip is to reinforce earth science concepts using examples found on campus. One does not have to travel to the Grand Canyon or Niagara Falls to reinforce many of the concepts discussed in class. This trip focuses on weathering and fluvial features, rock types, and biogeography but can be adapted to suit the interests and environment of the instructor. Background: Central Michigan University, Mt. Pleasant, Michigan is located near the center of Michigan's Lower Peninsula. Bedrock beneath campus is underlain by Paleozoic sedimentary rocks buried by over 300 ft of glacial drift. Surface deposits consist of beach deposits, ground moraine, and fluvioglacial deposits. Holocene Epoch stream dissection is responsible for what little relief exists on campus. Soils are loamy with numerous clay lenses. The original forest cover was beech maple with white pine, ash, and basswood. Trees viewed on today's campus reflect native Michigan varieties as well as exotic specimens. The average annual temperature is around 45 with winter temperatures rarely falling below zero and summer temperatures rarely piercing the 90 degree mark. Precipitation is distributed evenly throughout the year. Snowfall averages around 35" annually, one of the lowest totals for the entire state. The University was founded in 1892 but most of the buildings, sidewalks, and parking lots were constructed in the 1950's and 1960's. Our campus tour begins at Warriner Hall (pictured to the left) which was constructed in the 1920's. Stop 1: East Side of Warriner Hall--Part of stateliness of Warriner Hall is its ivy covered walls. There is a price, however, for using ivy as an ornamental. Observe the bricks below the ivy with a hand lens. What do you see? Write your answer in the space below. ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Biotic weathering takes two forms: chemical and physical. Ivy roots secrete acids to gain a foothold in the brick. Acids are also secreted to dissolve nutrients from the brick. Physical weathering occurs as roots wedge into brick cavities, prying loose pieces of brick and cement. Unlike chemical weathering, this process does not chemically 1 decompose the brick. Physical weathering does, however, aids the efficiency of chemical weathering by increasing mineral and rock surface area. Stop 2: Rock Garden North of Brooks Hall-Rocks boring? Never! Rocks are history capsules with tales to tell on how they were created. This stop features rocks from the three rocks classes: sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. The conglomerate is readily identified by white pebbles encased by a tannish cement. The well rounded to subrounded, as opposed to angular, pebbles suggest erosion in a stream or coastal environment before deposition and cementation. Choose a quartzite tombstone. Why? This metamorphic rock is highly resistant to weathering and erosion and will preserve an epitaph for millions of years. Note the cross bedding present which suggests changing water or wind currents acting on the original sand grains forming the rock. These sand grains eventually became cemented to form sandstone. Plate collision or mountain building produced the intense heat and pressure necessary to transform the sandstone to durable quartzite. The rounded pillow structures on the basalt suggest a lava flow within an aqueous environment. Quick cooling of the lava prevented the formation of crystals. Stop 3: Differential Weathering on the Heating Unit West of Brooks Hall--Compare the north and west facing walls for brick condition, color, and vegetation. Note that the south facing wall has greater signs of deterioration in terms of cracks, broken brick faces, and general discoloration. Look on the ground abutting the north facing wall. Moss is present. How can these differences be explained? In the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere the sun is generally found in the southern part of the sky. The south facing wall is more directly heated than the north or east facing walls. What other evidence supports that the south side receives more direct sunshine? Moss normally thrives where temperatures are cooler and soil conditions moist. The north facing wall, away from direct sunlight, provides a more suitable habitat for moss growth and propagation. At least two physical weathering processes are operative at this stop. Minerals with bricks expand by different amounts creating stresses within the cement and mortar. Repeated expansion and contraction cycles over the years have weakened the cement holding brick together eventually causing rock and mineral grains to mass waste from the wall. Freeze-thaw action can also result in patterns of differential weathering. This type of physical weathering is most active in December and March when temperatures hover around the freezing point. First, sunlight thaws snow and ice; then water seeps into 2 micro-fissures within bricks; finally, at night, water changes to ice. When water changes to ice it occupies a volume of around 10% greater than the liquid state. Expansion during this change in state widens fissures and breaks off pieces of brick. Finally, observe the southwest corner of the building. This area is the most weathered portion of the entire unit because brick corners are subject to weathering from two sides. Temperatures are highest when the sun is in the southwestern part of the sky. It is this southwest facing corner, therefore, that receives the greatest potential for processes of freeze-thaw and thermal expansion. The west and south sides of these corner bricks are weathered and are eventually "eaten through" creating the rounded corners observed on this side. If corners weren't the first casualties of weathering square rocks would be common. Stop 4: Miniature Sinkholes North of Dow Hall--The pitted surface, depressions, and caves observable in this limestone boulder display, in miniature, features associated with karst terrains. The miniature sinkholes observed in this picture could be created when joints were solutionally enlarged by acidic rainwater. Water combines with carbon dioxide to produce carbonic acid which attacks calcium carbonate, the main constituent of limestone. These depressions could also be created when the surface collapses due to the expansion of underlying caves. Humans have accelerated the rates of limestone weathering through air pollution, specifically acid deposition. The combustion of high sulfur coal from power plants releases sulfur oxides into the atmosphere which then combine with water droplets to produce sulfuric acid. Acid precipitation from human sources can lower the pH to 4.0 or lower, a thousand times more acidic than neutral. Sulfuric acid can also coat dust particles which, when hydrated, contribute to limestone solution. Stop 5: Bald Cypress Tree (Taxodium Distichum) on the Southwest Side of Moore Hall--On the annual academic pilgrimage to Daytona Beach during spring break the perceptive student may notice moss laden conifers thriving in the swamps of Georgia and Florida. This tree is a bald cypress, a native of the deep South. What is this tree doing almost a thousand miles outside of its range? Observe characteristics of site: First, note the heating duct in back of the tree. Second, the tree faces south. Like the wall observed during Stop 3, the south wall of a building receives more direct solar heating. Third, this alcove protects the tree from cold northwesterly winds. Collectively these site characteristics help explain how this 3 southern species can survive snow and occasional sub-zero temperatures. The bald cypress is an interesting tree. It's a deciduous conifer meaning that although it is a needle-bearing tree needles are shed in the fall. The cypress is like a maple tree in that it sheds its leaves (needles). The cypress is like a pine in that it has needles instead of leaves. So much for the idea that all conifers keep their needles. As a matter of fact, in any one year a conifer can lose up to one third of its needles as part of the normal growth process. Another interesting trait of the bald cypress is that it often grows bony stumps (knees) out of the water. These knees help support the tree which can grow to heights of over one hundred feet and help roots obtain oxygen. Stop 6: Root Wedging Northeast of the Student Activity Center--This stop features buckled pavement caused by the expansive forces associated with root growth. Sidewalks fractured by root growth will eventually have to be replaced. Roots can also force their way into sewage pipes causing tubs, sinks, and toilets to backup. While root growth can produce property damage, roots have many valuable functions. Roots retain soil helping to retard soil erosion. Roots breakup and help aerate soils, aiding in plant growth. Finally, of course, if we had no roots we would have no food! Stop 7: Delta Formed in Pond East of Student Activity Center--When vegetation is cleared by forestry or construction soils are often exposed to rainsplash and sheet erosion. Soil particles become entrained in surface runoff and are carried away by ephemeral surface streams. A rapid reduction in stream velocity occurs when streams or rivers empty into a body of water. The transport capacity of the stream is reduced causing sediments to fall out of suspension and deposited in the form of a delta. 4