Remodelling texts to develop comprehension strategies

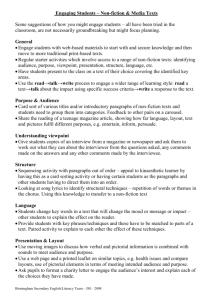

advertisement

Acknowledgements: Research for this document included the following: Education Dept Western Australia; First Steps Reading (Rigby Heinemann) 1997 Phenix, Jo; The Reading Teacher’s Handbook (Folens) 2000 Wray, David & Lewis, Maureen Extending Literacy, children reading and writing non-fiction (Routledge) 1997 Education Bradford Primary Literacy Team Remodelling fiction texts to develop comprehension strategies Make into caption books or film storyboard Make into concertina book – one event per page Re-order the story or information Invent your own ending – write or record on tape Re-tell the story using small models or puppets Paint a picture – particularly useful for re-interpreting poems Perform the story as a play in “readers’ theatre” Draw a flow chart or time line to describe the events or the changing settings of the story Draw a “feeling graph” to show how the character’s feelings change throughout the story: Start of the story Very scared End of the story Not at all scared Write a blurb or advertising poster to promote the book In pairs, improvise a telephone conversation to relate the story, prompting each other with questions and clarifications Write a newspaper report of the events of the story Similarly write the script for a television or radio news report Write in the role of one of the characters in the text. (For drama techniques and improvisations, see information in Speaking, Listening & Learning materials from NLS) Write a letter or post card in role to describe what happened after the story ended. Show the general structure of a story theme from a particular story e.g. “Where the Wild Things Are” - Maurice Sendack [Picture Lions] Sequence of events in text Max makes mischief in his wolf suit. His mother sends him to bed with no supper A forest grew in Max’s room and a boat appeared on a river. Max sails to where the wild things are and things look very frightening. Max tames the wild things by staring into their eyes without blinking. Max is made king of the wild things and they have a party. Max begins to miss home. Despite the entreaties of the wild things, Max sails home. General theme Someone does something wrong. They are punished. When he returns to his room, Max finds everything as it should be. His supper is waiting for him and it is still hot. It appears that there are some advantages in this punishment. A new danger appears. The danger is overcome by the skill or cunning of the main character. The character is honoured for this achievement. The character realises his faults. The character decides to return to the scene of the original crime to face the consequences. On returning, the character finds sure evidence that the original crime has been forgiven. Use the general theme to write variations on the theme without the constraints of the original characterisation and setting Find whether books by the same author use the same themes or whether there are different similarities in their work Find other stories with similar plots and identify one or more of the eight main story themes: The eight plots or story lines – is there any such thing as an original story? 1. Cinderella – rags to riches – virtue is recognised in the end 2. Achilles – there is a fatal flaw in what at first appears perfect 3. Faust – there is a debt to be paid from which no escape is possible 4. Tristan and Isolde – triangle 2 men + 1 woman or 2 women + 1 man 5. Circe – the spider and the fly – a cunning trap 6. Romeo and Juliet – lovers facing difficult circumstances 7. Orpheus – the gift that is taken back because it is not appreciated 8. David and Goliath – the hero or indomitable spirit –cunning is greater than strength Use stories with parallel plots (sometimes only observed in pictures e.g. “Rosie’s Walk” Pat Hutchins [Red Fox] ) and retell the sub plot e.g. in “Not Now Bernard” David McKee [Red Fox] the story could be told by the mother who describes her daily tasks and Bernard’s constant interruptions. Write a letter to the author asking questions about the book. The questions can be focussed on the text e.g. the characters’ motivations or they can be directed at the author. Make sure you send the letters (usually via the publisher) and expect a reply. Arrange for authors to visit. (This can be organised through groups of schools to ease financial pressure.) Devise questions or organise a debate to which the author can respond. Create a greeting card from one character to another (see “The Jolly Postman” J&A Ahlberg [Viking Kestrel]). Explain why it was sent and what the recipient’s reaction would be (orally or in writing) Design a gift box for a character in the text. Design the covering with appropriate graphics, then describe the contents and the reasons for your choice. This could also be designed as if the gift were from another character. Construct a map of the story and use this to retell - orally or in writing – the sequence of the story. Notes and captions can be added Leave home on bike Go into woods Dad picks me up in car Stop to pick flowers Get lost. Ask at house. They phone home. Home safe In role, organise a debate between the characters in the story. For example from “The Butterfly Lion” Michael Morpurgo [Collins] a group of children could represent the interested parties in Michael’s case (- his parents, the head teacher, the history teacher, Millie, Michael’s friend + any other characters who are not represented in the novel, but whom the children may feel could have a part). They could debate whether Michael should be punished when he returns from his escape. (See NLS Speaking, Listening & Learning materials for details on organising debates) Develop a board game – particularly suitable for stories with journey or quest themes e.g. “Firework Maker’s Daughter” Philip Pullman [Corgi]. See also non-fiction text restructuring ideas. Change the text type, e.g. rewrite the narrative as recount, story as a poem, instructions as recount etc. Change the setting of a story then investigate whether the setting affects the plot or characterisation Compose a soundtrack to accompany parts of the text. This could be performed by children using readers’ theatre techniques for the text and others using instruments or voices as the soundtrack. Relate the theme of the story to children’s own experiences. For example record a real occasion when the children have lost something special after reading about Dave losing Dogger (“Dogger” Shirley Hughes [Red Fox]). Make reading journals active and useful resources, not mere records of books read. See Lancashire Literacy Team’s journals on website: www.lancsngfl.ac.uk for examples of focussed, NLS objective-related activities to include in journals. The lists of texts read should be kept separately. This should record the start and finish date and serve as a record for assessment purposes The journal should be a personal record of responses to various aspects of literature, although the tasks may be set by the teacher. Some generic ideas for entries: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Personal responses to texts – giving reasons Drawings of settings or characters Drawings of a plan of the journey that takes place Predictions about the story at various points throughout the reading Lists of interesting or unusual words and their definitions Sentence, chapter or story openers that have interested you Comparisons between books by the same author Comparisons between books on the same theme but by different authors Suggestions of how you would change the story if you were the author Examples of phrases/poems expressing imagery that you particularly like Restructuring non-fiction texts to develop comprehension In order to represent information in a different format, readers must process the information i.e. work at understanding it and be able to draw conclusions from their research. Here are a few examples of the ways in which non-fiction texts can be restructured KWL charts – it is helpful to ensure that pupils begin to activate their prior knowledge before investigating any non-fiction texts. This also orientates children towards the topic and the learning is more focussed. QUADS grids are similar but allow more detail and help the children to direct themselves to resources for finding information Questions Answer Details Source This begins to break the answer to the questions into the short answer, the one the children may originally offer, and the long answer with the details discovered from the research. By adding the source of the knowledge, the child offers the opportunity to add to the knowledge and to allow others to confirm findings. Comparison charts – a great deal of information easily presented Name of plant onion carrot cucumber tomato. Fruit or vegetable vegetable vegetable fruit fruit Family trees – narratives about Greek Gods, for example, can be represented as a family tree to indicate an understanding of the relationships. Pie charts can indicate comparisons. Life cycle wheels and time lines show sequences of events. Sequential charts devised by the children can show understanding of the sequence of events without the constraint of a given framework. This can aid assessment both of and by the children. Mind maps, semantic maps or concept maps (all variations on a theme where similar concepts are grouped together around a central theme). These are particularly useful for visual learners as it is a graphic representation of the information gathered. It is useful for children to assess their own learning by drawing a concept map before studying a topic or reading a text then, using a different coloured pen, adding what they now know to this at the end Lists – this is often the first form of recording that young children devise for themselves and should be valued. Graphs – the labelling of the axes will be of particular significance when assessing comprehension. Diagrams - representing narrative in diagram format is again helpful to visual learners and those for whom writing is a challenge. Maps to indicate journeys of explorers, describe routes between destinations, show comparisons between climates, describe the development of civilisation etc. Flow charts indicating relationships between facts or the method of a procedure. Summarise facts into headings – reframe headings into questions to focus research. Fact files - as in information boxes in certain non-fiction texts. “Trivial Pursuit” cards with matching questions and answers. Board games – these can be designed to encourage consolidation of factual knowledge or to indicate a procedure Grids, pictograms, Venn diagrams – these are all ways in which a great deal of information can be exchanged with a minimum of writing e.g. Name of dinosaur Type of food Length of body Habitat Enemies Genre exchange This is where one written genre is transposed into another. It is more commonly used in fiction contexts but can be a useful way of developing comprehension. By re-ordering knowledge into a different genre or text type, the children are forced away from direct copying and into an exposition which shows they have really understood the topic. Here are some examples of the ways in which different text types can be used to present comprehension of non-fiction texts. Advertisements – children could design an advert for sailors to join James Cook on his second voyage to New Zealand. By describing what may lay in store for the volunteers, children can demonstrate their comprehension of Cook’s discoveries. Advertisements for rail tickets on Stephenson’s locomotive could include many facts about the invention. Holidays to the countries studied in Geography could be advertised, including all the features that have been learned After a design project, the finished product could be advertised so that the details of its design and construction may be described Using advertisements in this way will also bring in discussions about fact and opinion or truth and exaggeration. This is a useful tool in making judgements about the depth of a child’s understanding of a particular topic. Recipe – Recipes for embalming mummies could be written. A scientific experiment could be written up in the form of a recipe, although there may be PSHCE issues here and the suitability of the genre needs to be considered. Such a genre exchange will be most successfully used as a parody. Fax, e-mail or text message – the literary style of these genres demands that the presentation will be short and succinct. It is a good way of showing condensed versions of areas of knowledge. These formats are useful for presenting summaries of arguments. Newspaper/ radio/ television reports. Historical events are particularly suited to these genres. Diary entries – these can be based on studies of real diaries such as Pepys or Ann Frank, or they can be imagined entries by historical figures. Children can put themselves in the role of the scientist explaining the investigation in a personal journal or as a geographer describing the landscape etc. Eye-witness accounts – these are similar to above and allow children to put themselves into the role of the protagonist – scientist, geographer, musician, historical figure etc. Letters – letters home or to other historical figures could describe an historical event Playscript – the characters in the play could represent any topic. This could also be a format for presenting arguments for and against a particular event. Poem – taking the model of “The Iliad” or “The Charge of the Light Brigade”, sieges and battles can be represented in descriptive imagery or even metaphor.