Credit scoring from its origins to microfinance: a state-of

advertisement

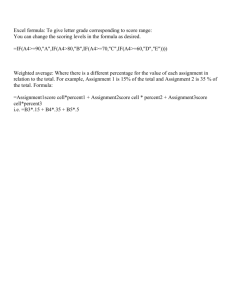

The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance (draft) Vitalie BUMACOV Applied Research Associate, Burgundy School of Business and Arvind ASHTA Professor, Holder of the Microfinance Chair, Burgundy School of Business, CERMi Abstract The paper traces the origins of credit scoring and its evolution, trying to understand both: the needs of lenders and how credit scoring responded to these needs. A special attention is given to the resemblance between the problems faced when credit scoring based on a statistical technique first appeared and the problems faced by microfinance lenders nowadays. The review of the literature on the evolution of the technique in mainstream finance can indicate possible developments of the technique in microfinance and vice-versa. Content Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Early works ..................................................................................................................................... 5 The commercial era ......................................................................................................................... 9 From consumer credit to corporate lending .................................................................................. 13 Modernism in credit scoring ......................................................................................................... 15 The new dimensions of scoring ..................................................................................................... 18 The microfinance era ..................................................................................................................... 20 Conclusions: The conceptual framework of credit scoring ........................................................... 21 Burgundy School of Business, 2011 Introduction We trace the sketches of the conceptual framework of credit scoring back to the late 1930s in the USA. The end of the Great Depression saw retail finance considerably increasing volumes. Small loans, relatively high interest rates and the efforts to keep operational costs low, constrained loan officers to increasingly base credit decisions on some mechanical rules. The practice of using different judgmental credit rating systems was not uncommon (Plummer and Young, 1940), although intuition and past experience were the only methods of selecting criteria to be taken into account in the effort to identify future safe and risky borrowers. The history of credit scoring begins with the study of David Durand in the area of consumer instalment financing published in 1941 by the National Bureau of Economic Research - a US nonprofit organization engaged in knowledge diffusion of how the economy works. The study was commissioned in 1937 after observing that consumer financing faced the Great Depression better and registered relatively small losses compared to other credit markets (Durand, 1941). The study pioneered the use of statistics in analyzing credit risk factors in consumer financing. The author statistically tested credit experience and intuition of 37 lending companies in identifying bad credit risks. The purpose was to identify consistent and time-proof credit practices. The research forged the pillars of the framework of the credit scoring techniques and opened the way for further research. The resemblance between the debate described in the study of Durand (1941) and the current post-crisis debates in microfinance is intriguing and promises interesting findings. These could be interesting equally for mainstream and microfinance practitioners, as well as for scholars. The academic analysis of actions and reactions that led to the current framework of credit scoring could provide many lessons, especially to the microfinance sector where the technique of credit scoring has been struggling to enter the market for the last decade but faces resistance from microfinance consultants who would like to differentiate the market from standard banking. The advance and diffusion of the theory regarding statistical discrimination of populations played a key role in the apparition of the credit scoring conceptual framework. The works of Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher that inspired Durand in his study are a good example. The thin link between eugenics and fundamentals of credit scoring can inflame the debate over the ethical raison d’être of credit scoring, especially when applied to microfinance markets. The year 1956 was the second important step in the history of credit scoring. Fair, Isaac and Company was founded on the principles that data can improve business decisions if used intelligently. Two years later, this pioneer company registered the first sale of a credit scoring system (Fair Isaac Corporation, 2010). Today it is estimated that two-thirds of world’s top 100 banks are clients of the company. From the academic view, the creation of a company and its subsequent success didn’t profit the literature related to credit scoring, as the company’s best practices and research findings became precious know-how that was strictly guarded and seldom exhibited, and that too for commercial purposes. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 2 Five years after the first credit scoring system was sold in the US, a paper published in the Journal of American Statistical Association noted that “numerical rating systems are not in widespread use” (Myers and Forgy, 1963). The authors confirmed that in consumer lending, “statistical credit scoring” represents an improvement over the judgmental-intuitive evaluation of credit risk. Several possible causes that prevented the spread of the technique were cited like the reluctance of credit executives towards application of new techniques and lack of experts willing to exploit this business opportunity. These half-century old conclusions, if transposed to a microfinance context should sound very present-day to those who advocate the use of credit scoring in MFIs. We must note that the success of credit scoring was held back by the lack of affordable means to perform sophisticated statistical calculations. It is not obvious today, but at that time this was a huge constraint. The use of computers, usually rented by the week rather than a proprietary tool, to perform a discriminant analysis offered significant advantages, but also severe limitations. In today’s microfinance industry too, cloud computing and software-as-a-service are being touted as possible rent based solutions to the management information systems (MIS) needs of the long tail of small MFIs (Ashta and Patel, 2010). We find that the main traits of the conceptual framework of modern consumer credit scoring were set by 1964. The description of the implementation and functioning of a credit scoring system in a financial institution (Boggess, 1967) allows us to make this conclusion. In the example of Boggess, loan applications were entered into the computer to be automatically scored and approved if policy limits were respected. Within a maximum of 24 hours, as opposed to one week before the introduction of the credit scoring systems, the credit department accepted or rejected the application. The asymmetry of information in microfinance has been well documented (Armendariz and Morduch, 2005). Common high default rates of microfinance in developed countries and even in developing countries during the post-crisis period indicate that credit scoring models have a role to play. While so far credit scoring was the exclusive domain of consumer lending, Edward Altman (1968) employed the discriminant analysis approach to financial ratios in order to predict corporate bankruptcy. Practical applications of his model were supposed to include business credit evaluation using bankruptcy prediction. The year 1974 marked a new stage in the history of the conceptual framework of credit scoring. The US Congress passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act that, including the following year’s amendments, prohibited discrimination in granting credit on the basis of race, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age and few more such criteria. In comparison with consumer lending, small business financing was seen by the academics as the next potential application of credit scoring. However, fears that commercial lending is not as homogeneous as consumer credit kept academics and practitioners away from that sector. No paper tried to measure statistically this homogeneity discrepancy and link it to the theoretical possibility (or impossibility) of developing credit scoring models for commercial lending. Fair, ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 3 Isaac and Company only in 1995 in partnership with Robert Morris Associates started to offer “pooled-data” credit scoring for small businesses (Fair Isaac Corporation, 2010). By the end of the century, in the developed world, the credit scoring technique was adapted and commonly used granting consumer and small business credit. The technique was adapted to be used in other credit related fields like collections and targeting prospects. Simultaneously, academics started to look for credit risk evaluation in developing countries. Laura Viganò (1993) proposed the application of a quantitative model for evaluating creditworthiness of individually operated small and micro firms based on multivariate discriminant analysis in Burkina Faso. She concluded that the use of relatively simple credit scoring techniques in development banks has some advantage and demonstrated the applicability of the credit scoring framework in less developed countries. This study (Viganò, 1993) in the microfinance sector marked a new stage in the history of credit scoring and opened the way for further research. In the area of micro loans, credit scoring still experiences problems similar to the ones consumer lending experienced in the USA, but in a different time and context. The analysis of these differences can help us predict the future of credit scoring in microfinance. Our review of the literature doesn’t stop at the threshold of the new millennium. The works of Mark Schreiner and other academics working in linking credit scoring to microfinance are studied. We conclude by presenting the consolidated conceptual framework of the credit scoring technique. It can be applied to consumer, business and micro loans. Any improvement of the framework has the advantage of improving the use of credit scoring in all concerned loan segments. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 4 Early works The set of studies in consumer instalment financing conducted by the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) in the last years of the 1930s and published in 1940 – 41 represent clearly the base on which the framework of credit scoring was built. The NBER, as a nonprofit organization, was engaged at that time in researching and disseminating knowledge about essential economic facts. Instalment financing was one important economic activity. Loan outstanding of this sector doubled from 1934 to 1938, as shown by the reports of a hundred US banks (Chapman and associates, 1940). The first NBER study “Personal Finance Companies and Their Credit Practices” edited by Ralph A. Young and associates, and published in 1940, focused on all retail lending, defined as a transaction where the consumer receives goods or money and engages himself to pay the price and incurred interests at regular intervals. Home mortgage credit was excluded due to specificities of such products. Personal business finance contributed significantly to the growth of consumer credit. A “close cousin” of the current micro loan, the amount of a personal loan was generally limited to 300 USD and maximum legal interest rates were 2 to 3.5% per month, depending on the State. The supply of personal loans was encouraged “to combat the loan-shark evil, which had arisen because the usury statutes prevented the profitable lending of small sums at legitimate rates… If licensed credit facilities are to be provided to low income groups legal rates must be high enough to encourage profitable operations” (Young and associates, 1940). If we ignore the date when the study was conducted, the above quoted text can describe the state of microfinance in numerous countries nowadays. This shows that following developments in this paper are interesting not only from the historical perspective on how the framework of credit scoring evolved, but also how the problems which are similar to the ones being experienced by the microfinance sector were addressed. The need to reduce transaction costs and enhance the appraisal of risks was obvious in a competitive environment. The third NBER study titled “Commercial Banks and Consumer Instalment Credit” by John M. Chapman and associates, published in the same year, presented the problems experienced by lenders. These lenders were conscious that some characteristics of the applicants are related to their credit risk. Such items were collected and considered in the evaluation. For the credit risk, two main factors were considered to be important: willingness and ability to repay the loan. Information as personal characteristics of the applicant, income, net worth and other financial characteristics were considered to be important predictors of the ability to repay. “On the basis of experience, and to some extent intuition, the loan officer decides which applicants are more likely to default than others or which loans are likely to involve collection costs so great as to render the transaction unprofitable… Lenders need to know the relative importance of as many credit risk factors as can be isolated, and in making a final decision on a loan application the responsible officer must give due weight to each factor” (Chapman and ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 5 associates, 1940). Second part of the citation defines the main problem that credit scoring is supposed to solve. In order to identify factors the notion of index of bad-loan experience was introduced and defined as percentage of bad loans divided by percentage of good loans. The index was calculated for each item or class of items that the factor comprises. A supra-unit index indicated that the item gathered relatively more bad loans than good loans, by consequence the item could be a possible risk factor if found statistically significant. Of course, some high indexes could be just the result of the chance. The higher the index, the higher the odds that the item has credit risk prediction power. The same works for low indexes. In this case the item would gather a significantly larger share of good loans than bad loans. In general, if the item is an indicator of risk, than the factor is. If we find that young clients tend to be bad clients (item: aged 25 years or less) then the age (the factor) could be an indicator of risk: high risk for young applicants, low risk for older applicants. The authors, based on samples of good and bad clients coming from different financial institutions found the most significant indicators of credit risk the following items (and factors): possession of a bank account, stability of employment, nature of occupation, permanence of residence, ownership of real estate and industrial affiliation. They made an important remark that challenges researchers till today. “Since these borrowers had already passed through a selection process at the hands of credit men, the sample cannot be considered completely representative of the general run of personal loan applicants” (Chapman and associates, 1940), meaning that there might be other important factors that didn’t manage to be correctly represented in the samples because credit officers screen applicants and may eliminate an important proportion of what they perceive as bad risks. The second NBER study, “Sales Finance Companies and Their Credit Practices” by Wilbur C. Plummer and Ralph A. Young (1940), presents a functioning credit rating system, which we consider to be the closest ancestor of a credit scoring model. The use of such systems was not uncommon in the late 1930s. In some cases a rating of good, fair or poor was entered for each item considered as an indicator of credit risk. The final rating would represent the average of favorable and unfavorable indications. “In other cases a specific grade is entered opposite each item, and the sum of the grades serves as the index of credit risk” (Plummer and Young, 1940). The use of such systems is not uncommon today, especially in micro and SME lending. The work of David Durand, which is one of the following NBER studies, published in 1941 under the title of “Risk Elements in Consumer Instalment Financing”, marks the first important step in the development of the technique of credit scoring – the beginning. We consider this study to have pioneered the use of statistics in analyzing credit risk factors in lending. The author used a large sample of 7,200 consumer loans disbursed by 37 financial institutions: commercial banks operating personal loan departments, personal finance companies, industrial banking companies, automobile finance companies and appliance finance companies. Borrower characteristics were copied from their loan application forms. These included: age, sex, marital status, dependents in the household, stability of employment, permanence of residence, and other socio-demographic variables. Also borrower’s assets and liabilities, and loan characteristics like amount and number of installments were available. No information ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 6 about past credit behavior was collected, nor information on “matters like physical or mental health, which are certainly germane to risk problem, but which obviously do not lend themselves to analysis in a statistical study of credit risks” (Durand, 1941). The author highlights the limitations of the sample due to screening of applicants by the loan officers. Later, different techniques as the reject inference were to be developed, but at that time the solution proposed by Durand was “to make experimental loans, which amounts to a temporary lowering of standards, with a possible increase in losses, and a subsequent adjustment of standards on the basis of the newly gained experience” (Durand, 1941). This solution is still considered in present days. Durand (1941) makes the interesting remark that in practice it is difficult to make a precise distinction between good and bad loans. If the net revenue from a loan doesn’t cover the expenses to recover it, it is certainly a bad loan. If the loan and interest are repaid in full and on time it is considered by lenders to be a good loan. Delinquency has a role to play in making the distinction. Serious delinquencies lead to additional expenses like collection or court actions with no guarantee of a return. Since it is impossible to determine accurately, in advance, when a loan ceases to be profitable, this has to be estimated. The author proposed several criteria by which a commercial bank could identify bad loans for the sample he needed for the study: “loan was more than 90 days delinquent; comaker [cosigner] paid all or part of loan after demand by bank; legal action was taken; loan was charged off” (Durand, 1941). By simply analyzing the mathematical means of all linear factors in good loans and in bad loans, differences between these two mutually exclusive groups are observed. These differences are even more obvious when using the previously defined index of bad-loan experience by classes of the factor. About the sampling, Durand finds another interesting aspect. Even if large samples are preferable, collecting thousands of cases is impossible or too expensive, and a sample of 100 good and 100 bad loans may be adequate for empirical significance. For the microfinance sector these findings should be very important as sampling in many MFIs is still a big problem due to bad databases or lack of MIS. Some institutions don’t have many bad loans, but still find a scoring tool useful to be able to serve more clients by gradually lowering screening barriers while controlling the credit risk. From experience, we may say that the “100 good and 100 bad loans” for a credit scoring system is possible within the microfinance reality. Durand (1941) identifies another threat: over time, risk experience to be used for future estimations may change. One of the proposed solutions is to limit the study to short homogeneous periods. The fact that such periods have to be “recent” is not mentioned but seems to be implicit. In order to pass from the influence of isolated credit factors on the bad-loan experience to a global approach, Durand (1941) employs the concept of a “credit-rating formula”. It is a formula which combines most important factors and the corresponding weights for the classes. Computed, the result is a credit-rating score, which is used as the basis for accepting or rejecting ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 7 loan applications. Today, the term “scorecard” and “algorithm” have replaced the expression “credit-rating formula”, but in the essence, each scorecard is a formula and the definition for the later remains unchanged in the industry till present days. Intuitive-subjective credit-rating formulae have been created before and in use in certain financial institutions. Durand (1941) created the first “purely objective credit formulae by statistical methods”. This stage marks the beginning of credit scoring. The statistical approach towards the selection of factors that predict credit risk is an essential part for the conceptual framework of credit scoring. There is no credit scoring without empirics. Durand points precisely the advantages of credit scoring. Loan officers can assess ordinary applications faster and “most of the routine work of investigation to be handled by rather inexperienced and relatively low-salaried personnel” (Durand, 1941). The success of the formula is tested using the distribution of good and bad loans by that formula. By virtue of the multivariate analysis, the “efficiency index” is higher than the highest index of all individual factors. The index used by the author measures half of the sum of all absolute difference between percentages of good and percentages of bad loans for all classes of the factor. The same index is calculated for all classes of score in the distribution. The sum of the differences is zero. The highest possible index is 1, indicating that the risk factor has such characteristics that gathers all the bad loans and none of the good ones. In such case credit scoring is useless as all bad loans can be eliminated using one factor. The lowest index is 0 – no credit risk discrimination potential. A perfect scorecard will have an index of 1, which is never the case in practice. Durand (1941) used the statistical technique of discriminant analysis to generate the scoring formulae. He also presented a formula to be used in fixing the cut-off, which takes in account the profitability of the clients. His work lays down the principles of the conceptual framework of credit scoring. We retain that for developing a credit scoring formula we need a representative sample of good and bad borrowers. We need to know their detailed profiles: the more characteristics the better. Statistical methods are used to identify items and their weights to compose the formula. The resulting scoring will be used to accept or reject applicants based on a certain cut-off. Obviously, statistics may contradict some subjective ways of thinking. Durand (1941) discovered that women tend to be good risks to the surprise of some lenders that were convinced of the contrary. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 8 The commercial era The revolutionary approach of Durand required some time to reach scholars and the professionals involved in consumer lending. That explains the small number of research studies covering the topic of credit scoring till the 1960s. On the contrary, consumer lending continued to grow in USA touching larger segments of the public, while Europe was recovering after the war. In the paper “Development of Numerical Credit Evaluation Systems” published in 1963 by James H. Myers and Edward W. Forgy comes with important findings and improvements to the conceptual framework of credit scoring. At a point, the growth of consumer credit in USA became unsustainable, since under the pressure of the demand, many financial institutions grew “beyond their capacities to train and maintain an adequate staff of experienced credit evaluators” (Myers and Forgy, 1963). Microfinance today experiences similar problems. If that situation was favorable for the diffusion of credit scoring in the USA, now it is quite the time for the technique to invade micro lending. Durand (1941) used aggregate data instead of building scoring formulae based on each institution’s individual sample - fact that could explain the reduced efficiency of his scoring formula. He used a sample to build the formula and the same to test it, which supposes a risk of biased results. Myers and Forgy (1963) on the contrary, worked with the data from one financial institution. They engaged in a battle for predictive effectiveness of scoring formulae. A new component that was added to the framework is the use of a “hold-out” sample. There are chances for a formula that can separate well the good and bad clients in the original sample to have no predictive power at all. Since then, the use of a separate sample to test the effectiveness of the formula became mandatory. The authors used different statistical approaches to identify the items and corresponding weights to be included in the four resulting credit scoring formulae: discriminant analysis (same used by Durand), stepwise regression, equal weights for pre-selected predictive items and a “doublediscriminant analysis” consisting of selecting a subsample of good and bad loans which received the lowest scores under the first approach and re-performing the analysis on this low-end subsample. Myers and Forgy (1963) found that a smaller number of variables (12) will predict almost as well as all (21) variables that had significant risk discrimination potential. The “face validity” was important for the institution in the process of validation and use of the formula. If the lender cannot understand and justify different variables that are selected, there are chances that credit scoring won’t be used, or employed in a wrong way. In spite of substantial improvement over judgmental approaches, credit scoring was in limited use. Possible reasons were reluctance of experienced credit executives, difficulties in developing and implementing credit scoring or “the unwillingness on the part of statistical consultants to invade the domain of the credit manager and do the selling job necessary to transform such idea into a successful and useful operating tool” (Myers and Forgy, 1963). ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 9 It is likely that the authors were not aware that for 7 years in California a business named Fair, Isaac and Company (FICO) was proposing credit scoring solutions for financial institutions. Actually it was in 1958 when the company decided to play big by sending letters to the 50 biggest national financial institutions inviting them to receive explanations on the concept of credit scoring. One credit grantor responded and in the same year the company sold its first credit scoring system. Today 90 of the 100 largest financial institutions in the US and all the 100 largest US credit card issuers are FICO clients (Fair Isaac Corporation, 2010). The apparition of a business player confirmed the potential of the technique of credit scoring predicted by academics. The credit scoring industry has been born and with it the distinction between the public interest and private competitive advantage in the field of predicting credit risk. As the company’s know-how was strictly guarded, we continue the research for information on the academic side. In the paper of Paul F. Smith “Measuring Risk on Consumer Instalment Credit” published in 1964 in Management Science we find a reference of a paper written by Earl Isaac named “Statistical Problems in the Development of Credit Scoring Systems”. It appears to be the only paper about credit scoring written by the mathematician that co-founded and managed for a long period FICO. In the same paper Smith (1964) proposes a different methodology for calculating the credit score by adding together the “bad account probabilities” corresponding to each item of the applicant. The probabilities, all positive, are calculated using a sample of good and bad loans. The author also proposed to multiply by 1,000 these probabilities for easier computing of the sum and clearer interpretation of the results. This multiplication by 1,000 would be adopted by some practitioners, but it won’t help the technique, or the interpretation. It helps only people that prefer integral numbers instead of fractions. The scoring methodology, even if simple and clear, was rejected as not empiric, even if probabilities were used. Was considered the proposal to compare the scoring formula with the traits of rejected applications, to judge on possible bias of the sample. In his short article titled “Concepts and Utilization of Credit-Scoring Techniques” published in the journal Banking in 1966, Martin Weingartner presents the state of the art of credit scoring in USA. He links the increasing success of the technique with electronic computers becoming available. The author mentions the risk based selection of loan characteristics – the loan amount depends on the credit score, no evidence of risk based pricing. Weingartner (1966) highlighted the importance of performing tests before credit scoring is used by the institution. Besides the validation using the hold-out sample, the author suggested using the formula to score current delinquent accounts to observe if these receive low scores. This easy to perform test would not be included in the conceptual framework of credit scoring, but it certainly can be used every time when extra confidence in the formula is required. For the first time in the literature the importance of a field trial is mentioned. The procedure supposes the use of credit scoring first by only a few loan officers or by only one branch out of the entire network. The procedure is intended for “training as well as for ironing out difficulties that arise” Weingartner (1966). This is not a constituent of the framework but a mandatory stage from a pure practical view of the implementation process. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 10 Post-implementation reports certainly are a constituent part of the conceptual framework of credit scoring. Weingartner (1966) proposes “a running barometer of the quality of credit granted, and of the quality of applications turned down”. If the management on a regular basis analyses the scores of applications that were accepted and of those that were rejected, the overrides could be identified and examined. The average score of accepted applications and the trend would indicate the quality of newly engaged portfolio. New research trends in credit scoring include efforts to build formulae that predict the profitability of loan accounts instead of the chances of registering delinquencies, but also the use of the scoring technique in identifying accounts more likely to respond to different collection procedures (Weingartner, 1966). The latter, even if similar to credit scoring, will be referred as “collection scoring” and by consequence excluded from the current framework. Figure 1 - the graph used by Weingartner (1966) to explain the use of the credit scoring distribution We conclude that the main traits of the conceptual framework of modern consumer credit scoring were set by the mid 1960s. The previously cited papers, plus the description of the implementation and functioning of a credit scoring system in a financial institution done by William P. Boggess in the Harvard Business Review in 1967 in a paper titled “Screen-test your credit risks” allows us to make this conclusion. In the company that implemented credit scoring in 1964, loan applications were automatically scored by the computer if policy limits were respected. Within 24 hours the credit department accepted or rejected the application based on the score. Before, this task required up to one week. The financial institution experienced an increase in staff of less than 2%. “The company cut bad debt losses enough to realize a $1.5 million profit improvement on more than $100 million in sales in the first full year of the system’s operation” (Boggess, 1967). MIS combined with the virtues of credit scoring give the lender the possibility to operate procedures that adapt the strategy of the company to shifts in applicants’ population. The concerned company developed a new scoring formula each 6 months and track changes in the ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 11 weights of characteristics included in the scoring formula over time (Boggess, 1967). An economical approach would consist in tracking changes in characteristics of applicants and develop new formulas when shifts are considered significant. Another approach would recommend the replacement of the formula only when the risk discrimination power starts to reduce. The inconvenient is, as Boggess (1967) noted “nine months’ time, rather than a long period, was necessary before the good and bad accounts could be predicted with acceptable accuracy”. The credit behavior maturity is a mandatory concept for institutions willing to develop a credit scoring formulae with relatively recent data. This is often the case with microfinance institutions. It means also that the results of using a scoring formula will be seen in a certain time. So, if the risk discrimination power deteriorates, the institution has to react fast. The scoring reports having the function to control the use of credit scoring come to complete the conceptual framework. THE POPULATION: MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS: Two representative samples of recent or current borrowers whose mutually exclusive status of good or bad risk is known or can be precisely estimated. Statistical link between characteristics of the profile of the borrowers and their status as good or bad risks The detailed profile of borrowers at the moment of loan application is known. SCORING FORMULA: b.) the hold-out sample Formula is built using the development sample and tested on the hold-out sample. Results are compared with the rejected sample Good risks When computed the formula gives a score CONTROL: a.) the formula development sample bad risks rejects Computation of the formula gives a score DISTRIBUTION: USE: CUT-OFF (S): Applicants are scored and are accepted or rejected Determination of the cut-off score based on the analysis of profitability of good loans and losses generated by bad loans The result of scoring the holdout sample is a scoring distribution Figure 2 – the conceptual framework of credit scoring as existed during the middle of the 1960s. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 12 From consumer credit to corporate lending While credit scoring was the exclusive domain of consumer credit, in corporate lending academics and practitioners started to consider statistical techniques to replace or enhance the traditional ratio analysis in evaluating the health of the companies. Edward I. Altman (1968) employed the discriminant analysis approach to predict corporate bankruptcy using financial ratios, which gave better statistical significance when analyzed within a multivariate framework. Altman (1968) used only ratios, ignoring other important categories of variables like loan variables or business-demographic variables. At that time no paper addressed seriously the importance of business-demographic variables in predicting credit risk. Altman concludes that the model, in spite of the potential it has, “should probably not be used as the only means of credit evaluation” (Altman, 1968). Altman’s contribution to the conceptual framework of credit scoring is important as it opens it for business loans. So far, credit scoring was used exclusively in consumer credit where the subject to be scored was the person applying for a loan. If Altman’s findings were to be applied in practice, then the framework would include a second category of subjects – the companies. The profile of a company is different from the profile of an applicant for consumer credit. Yair Orgler (1970), inspired in part by the work of Altman, focuses on the use of the credit scoring technique on current (in-progress) commercial loans. The proposed purpose was not to accept or reject but to review periodically the quality of the loans already disbursed. He makes the interesting remark that business borrowers in general do not belong to large homogeneous populations as do customers for consumer credit. This problem was not yet defined in scientific terms by the academics. The condition of homogeneity of the population of subjects to be scored becomes part of the framework of credit scoring. Due to the fact that commercial borrowers are so diverse and their loan products so varied in terms of maturity, amount and security, the application of a credit scoring model for approval of loans would be less appropriate then using it for periodic quality reviews of current loans. “Its main advantage is in releasing loan officers and bank examiners from routine evaluations of all loans and allocating their time to a small proportion of riskier borrowers” (Orgler, 1970). The use of the scoring technique to measure the evolution of the credit risk during the course of the loan is certainly new, interesting and useful to some extent, knowing that corporate loans have longer maturities and meantime changes can affect seriously the credit risk. The fact that during the reimbursement of the loans new information comes regularly to enrich the profile of the borrower, especially data on current payment behavior, makes this type of scoring formulas relatively robust in predicting defaults. Financial institutions, on the other hand, have limited freedom of action. The risk can not be avoided as the money has been already lent. Corrective actions only can be done. This particularity, like in the case of collection scoring, can not be accommodated by the conceptual framework of credit scoring. A new framework, very similar to the one of credit scoring, emerged and its importance would soar with the extension of Basel Accords. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 13 This divergence between consumer loans and corporate loans does not exist in microcredit. Micro lending addresses generally poor and self-employed populations. The borrower in a majority of cases is the person, his household and his small entrepreneurship, all in one. His business and household are assessed as these will generate the money to reimburse the loan. If not existing as formal and trusted documents, a balance sheet and an income statement, simplified to the maximum, will be created and assessed using ratio analysis or similar procedures. The applicant – the person – will be evaluated using the consumer lending techniques. Several scholars, including Yair Orgler (1970) mention the dissertation of David Ewert (1968) that proposed a credit scoring formula to be used by wholesale distributors in granting trade credit to retail stores. As the stores were mostly small – one-owner companies needing trade credit of amounts similar to the consumer credit – the formula used a combination of variables describing the owner – the person applying for the loan and variables describing the financial position of the store – the company to be the legal responsible for the loan. From this experience, we will retain that the profile of the owner of the business as well as the profile of business itself may be important in predicting the credit risk of small companies. When transferring the technique of credit scoring, from consumer lending to business credit, there is an area where these two confound. This is certainly the case of micro lending. The phenomena known as “informal economy” has certainly a role to play in blurring the limits between the physical person and the business entity he owns. As the literature review conducted so far involuntarily focused on the US papers, none addressed this issue. With the credit scoring technique spreading in the developing markets, this issue will reappear. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 14 Modernism in credit scoring The early 1970s saw the industry of credit scoring growing. FICO started collaboration with Wells Fargo – major financial institutions in the US. The credit scoring provider already was planning to export the technique to Europe (Fair Isaac Corporation, 2010). Increasing number of academics approached different practical and concrete topics related to the scoring technique. Emphasis is put on costs and net present value of loan repayments (Edmister and Schlarbaum, 1974), but also on best statistical techniques to be used and a better definition of good and bad risks. The role of credit bureaus in helping identify bad credit risks is mentioned. Some serious works are focused on low income populations. Muchinsky (1975) finds that two dimensions of the borrower's repayment behavior are critical to its classification by the lender as good or bad credit risk. One is obviously the delinquency and the second: the anticipated repayment of a loan. The fact that the borrower reimburses the loan prematurely is susceptible of making the account unprofitable as interest margin perceived only for a short period doesn’t cover transaction costs. This perspective enriches the perception of bad clients. The efforts to use the scoring technique to facilitate extension of credit to low income clients indicate a certain maturity of the concept of credit scoring in the US. Certainly, the Consumer Credit Protection Act (CCPA) of 1968 had a major role in regulating the industry. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 had also notable implications. Including its 1976 amendments, this Law prohibited discrimination in the granting of credit mainly on the basis of race, religion, sex, marital status and age. These ethical concerns were formalized within the legal framework and in this way adjusted the conceptual framework of credit scoring in USA. Even if many countries are not concerned by such limitations, ethical and sound selection of variables predicting the credit risk is a rule that seems to be obeyed in part by the practitioners. Gender and marital status as exceptions are often used in credit scoring formulae designed to score low-income populations in the virtue of “positive discrimination”. In microfinance, women in spite of proven better credit behavior are more often refused access to credit (D'Espallier, Guérin and Mersland, 2009). Divorced women experience even stronger exclusion. If a scoring formula can help increase the chances of excluded female borrowers to get loans while improving the quality of the portfolio, then many might be seduced by such opportunity. The US National Commission on Consumer Finance created by the same CCPA ordered a research to determine the feasibility of a credit scoring system applicable to low income consumers. The conclusion was negative indicating that variables most likely to discriminate credit risk of low-income consumers are presently excluded from standard loan application forms (National Commission on Consumer Finance, 1972). Joan Tabor and Jean Bowers (1977) conclude that credit scoring should be re-designed to be employed efficiently in evaluating credit quality of low income consumers. Establishment of household financial consultants is suggested – an idea that certainly doesn’t contribute to the initiative of lowering transaction costs. Donald Sexton (1975), on the contrary, found that only few variables with credit risk predictive power differed between high-income and low-income households and thus could not make the ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 15 conclusion that different procedures are required for high- and low-income populations. We believe that this issue is reduced to the question of homogeneity of populations, and low income borrowers, except the income, may be different in many aspects. For the conceptual framework we note that it is possible that low-income customers have different credit behavior habits that may be considered separately. It is important to mention that in the effort of extending credit in a sustainable manner to poor US borrowers new techniques of cost reduction like credit scoring were seriously considered. The “in-house knowhow” character of credit scoring systems used by the financial institutions represented an increasing problem for the scholars, who found it difficult to relate and research on how well the industry incorporated new tendencies and legal requirements into practice. The new regulation required statistically sound scoring systems be constructed using empirical methodologies, but no precise standards were imposed. The hypothetical obligation to demonstrate the soundness of a scoring system in Court made the scholars focus on different technical aspects and assumptions that were ignored, as long as the model was showing evidence of credit risk discrimination on the hold-out sample or in practice. In the absence of case studies, Robert Eisenbeis (1978) analyzed the credit scoring systems developed by academics at that time, hoping that these were reflecting the systems in use by lenders. Since the majority of models were developed using discriminant analysis, he pointed out statistical problems the technique had and warned the public on the inherent risks. With the apparition of credit bureaus selling information on past credit performance, the cost of extra information was considered in different credit granting schemes (Eisenbeis, 1978). For the conceptual framework of credit scoring, such considerations foresaw new enhancements. If a scoring formula predicts the credit risk accurately using few variables, why pay for extra information? On the contrary, for the loans in the “grey area”, at the limit of the cut-off, if additional information can help discriminate better, extra costs are clearly justified. Can one scoring formula accommodate such features? James Ang, Jess Chua and Clinton Bowling (1979) were amongst the first to build a nonparametric credit scoring system. They applied the decision tree technique to a credit scoring related problem. The result is not a scoring formula as before, but an algorithm represented by a tree-like scheme. The characteristics of the scored subject guide the user through the nodes and branches of the tree till the estimated bad or good class of the applicant is determined. The use of “automatic interaction detector analysis” showed that the relationships between late payments and some borrower variables are nonlinear. (Ang, Chua and Bowling, 1979). By consequence, linear credit scoring models may not be always appropriate. Since this technique remains to be a multivariate analysis, the conceptual framework doesn’t change. We will note however that besides the discriminant analysis which was applied first by Durand (1941) to the loan screening question and since, extensively used by academics, and the regression analysis, that started being popular by the end of the 1970s, other non-parametric techniques belonging to the multivariate analysis may be used in identifying good and bad credit risks. We conclude that by the end of 1970s, credit scoring was a recognized industry. The concept found its first use in Europe, implemented by FICO in a bank in 1977 (Fair Isaac Corporation, 2010). The company by that time delivered approximately 500 systems to approximately 200 ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 16 customers, including about half of the 50 largest US banks and 20 US finance companies, according to the testimony of William Fair - that time head of FICO, in front of a Senate Commission (U.S. Senate, 1979). The framework of credit scoring entered its modern times. From this perspective it’s hard to imagine that the concept of credit scoring will change significantly. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 17 The new dimensions of scoring From the perspective of the 1980s, looking back at the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which was originally perceived as a possible threat to credit scoring, we have a different impression. Since the use of some discriminatory but predictive variables was prohibited, many feared an overall reduction in predictive power of scoring systems, even if a study showed no negative impact (Nevin and Churchill, 1979). However, since judgmental systems were strongly criticized as being subjective and thus prone to discrimination evaluation of credit officer, credit scoring had to gain. It was supposed to be objective and under the new Law, respectful of ethical issues. Noel Capon (1982), one of the strongest opponents of the use of “brute force empiricism” in credit scoring, remarks that the credit scoring formulae in use included variables with no obvious or logical relationship to creditworthiness, while other variables that seem to be directly related to the capacity of repayment, like income, may not be included at all. It is true that with computers becoming more popular and powerful and statistical packages becoming more userfriendly and affordable, many practitioners engaged in a “wild west” conquest of credit statistics to find new predictive variables or “surrogates” for prohibited variables. In parallel, the credit bureau industry grew, supported by the continuous expansion of the consumer credit market. The databases had to expand in volumes and complexity. It was not surprising that in 1981 FICO introduced the first credit bureau score (Fair Isaac Corporation, 2010). Against a larger fee, the inquiring financial institution would henceforth receive not only the existing credit record of the applicant but also a credit score. The score could be used solely or in combination with the institution’s appraisal result in deciding to grant credit or not. The presence of an external score does not affect however the conceptual framework of credit scoring. A new concept called “expert system” was supposed to have serious implications in the credit business, particularly in consumer credit. Backed-up by developments in the IT industry, expert systems were software designed to imitate the way of thinking of human experts. Holsapple, Tam, and Whinston (1988) presented a summary of application of such techniques in finance. We find that some financial institutions were already using expert systems in credit analysis and approval. The advantage of a “cyber expert” is the possibility to have an output in real time or much faster than human experts will provide the decision. Such tools, having characteristics belonging to the artificial intelligence domain, may go beyond the function of decision support. In combination with a functional credit scoring system with clearly defined scoring strategies, an expert system may take credit decisions for the big majority of loan applicants in real time, leaving to the loan officers the task of treating applications falling in the grey area, if such areas are defined. Since the quality of the decision can be measured with hindsight at later stages, engineers imagined expert systems acquiring knowledge automatically from past experience and particularly this kind of artificial intelligence can have implications for the credit scoring framework. The principles of credit scoring won’t change, but what might change is the way the scoring formulae are kept up to date. This is especially important because any scoring algorithm ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 18 tends to lose its credit risk discrimination power over time due to the evolution of the society. If notable changes occur, and the financial institution is able to trace them, the scoring formula has to be recreated, as adjusting a formula may be statistically impossible. In both cases the operation is expensive, so a scoring system that adjusts itself to the changes of the environment seems to be an interesting innovation. With the globalization, the technique of credit scoring has started being disseminated across the world. Papers coming from non-US academics appear but their work doesn’t bring anything new to the framework of credit scoring. Particular statistic questions continue to be the most researched topics. The efforts to approach the credit scoring problem from a multi-period perspective or from the long-time discussed profitability perspective struggle to find their way into practice. The credit scoring principles progressively “invaded” other banking and non-banking sectors. It is currently employed in banking fraud detection, in marketing, but also in the insurance industry to cite just a few. However, every use of the scoring technique outside the credit granting procedure is considered by us to be outside of the conceptual framework of credit scoring. On the other hand, the application of the scoring technique in approving loans to small and micro businesses, but also to mortgage loans, enriches the framework. In 1995 FICO in partnership with Robert Morris Associates developed a credit scoring tool for small business. The concept of “pooled-data” was introduced to solve the problem of heterogeneity of profiles of small businesses (Fair Isaac Corporation, 2010). While developed countries progressively adopted the credit scoring techniques, Laura Viganò (1993) studied the applicability of credit scoring on individually operated small and micro firms in Burkina Faso. She concluded that the use of relatively simple credit scoring techniques in development banks in less developed countries has some advantage. These findings are encouraging, knowing the demonstrated ability of such systems to cut transaction costs and enhance the decision making process. Credit scoring enters a new stage: the development finance. In developed countries, the technique reached a certain threshold of perception and understandability. Obviously, new statistical techniques can give even more predictive power, but the face value of the technique has to remain clear to those that decide to buy or implement credit scoring in their financial institutions. These deciders are rarely advanced statisticians. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 19 The microfinance era We perceive the introduction of credit scoring in microfinance as a new stage in the history of credit scoring. Researchers used the technique of credit scoring in a similar context as Duran (1941) used it in USA after the Great Depression. The concept did a full cycle to return to the origins of the problem of granting loans at lesser cost to (micro) borrowers. As Mark Schreiner noted in his cornerstone paper “Credit Scoring for Microfinance: Can It Work?” published in 2000, credit scoring for microfinance can work. The difference is in the information, which is usually qualitative and informal. The new challenge of credit scoring is incorporating and adapting to this constraint. Neither Durand nor other scholars treated the topic of using informal data for credit scoring purposes. Unfortunately, in many countries around the world, even amongst the rich, the informal and semi-formal sector represents an important share of the GDP. There are lots of people behind this economy that need financial services. Microfinance is a fair answer to a large majority of these needs. Although “credit scoring is one of the most important uses of technology that may affect microfinance” (Rhyne and Christen, 1999), we need to redefine the conceptual framework of credit scoring to allow its full application to micro lending. The development of the framework will serve as a guide for practitioners in applying efficiently credit scoring in microfinance. Credit scoring doesn’t have to be rediscovered, but adjusted and promoted in order to cut transaction costs and make the credit available to the excluded as long as the credit risk can be measured and controlled. The concept of information asymmetry pioneered by Stiglitz has a particular connotation in micro lending. Statistics have a major role to play in reducing the information gap as have onground investigations. Who thought before that the opinion of a neighbor of the applicant for a micro loan can be strongly correlated with his credit behavior? Such qualitative information can now be harnessed and incorporated in a credit scoring algorithm. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 20 Conclusions: The conceptual framework of credit scoring Credit scoring is a tool designed to help manage the credit granting problem. It is based on an algorithm that predicts the future classification of the applicant as a good or bad credit risk using the known profile of the subject, which belongs necessarily to a homogeneous and massive population. The algorithm is derived using a multivariate analysis technique that allows identifying characteristics of the profile and respective weights of recent or current borrowers whose status as good or bad risks is known. The assumption is that future borrowers will have a credit behavior alike past borrowers with similar profiles. Statistical significance and representativeness have to be respected. Due to the fact that past borrowers had been screened by loan officers during their approval process, the population of clients with known credit risk status is biased. The profiles of rejected applicants have to be confronted with the profiles of recent good and bad clients and results considered. In the effort to reduce bias, the algorithm is developed using a sample and tested on a hold-out sample. The discrimination power of the algorithm is measured and tested if statistically and economically significant. If acceptable, the credit scoring system is implemented and used in the process of screening loan applicants. Results of the use of the credit scoring system are regularly verified using reports. The population: comprises subjects interested in the loan products of the financial institution. A loan is a transaction where one part receives an amount of money or the goods bought using it, and engages to reimburse the same amount at a later date in one or more installments to the second part which bears the credit risk and perceives from the former an interest. Some subjects of the population received loans before, some were refused and some will apply in the future. One particularity of the subjects is the homogeneity and by consequence the needs of the subjects in mater of financial services are similar. We may consider all the applicants for a consumer personal loan as a separate population. Most important categories of populations are: consumer borrowers, corporate borrowers, small business borrowers and microfinance borrowers, but also mortgage borrowers. We may note that the concept of population can be extended to the applicants of other financial institutions offering similar loan products. If we analyze past applicants, then we notice that some were rejected as considered too risky. A large proportion received a loan and reimbursed it as agreed with the financial institution. These are certainly good borrowers and the financial institution probably proposed them to renew their loans. There are also few borrowers that didn’t reimburse the loan as agreed. Some of them reimbursed the loan in advance. Some defaulted and did not repay the loan outstanding. Some registered serious delinquencies and engaged with the financial institution in collection actions. In the big majority of such cases the financial institution lost money in doing business with the clients. By consequence such loans are bad and no new credit was extended to them. Exceptionally some delinquent loans may still remain profitable due to penalties charged on overdue capital or due to recovered amounts that would cover all extra costs plus the expected revenue. Such cases remain in the area of exceptional. Obviously, the profitability of each loan is the best indicator for it belonging to the mutually exclusive class of bad and good loans. Delinquency however serves as a good proxy and is used extensively as an indicator for identifying good and bad loans. Analysis of the delinquency has to be done to determine the kind of delinquency that leads to collection costs and default. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 21 Different procedures may consider the borrower in a multi-period frame estimating present and future profits generated by the client. We argue in the favor of simplicity. It also seems that simpler definitions of a bad loan imply better prediction power of the scoring model. No research can support or reject our thoughts. In the context of limited samples as is often the case of microfinance, current borrowers may be already classified as good and bad customers with certain accuracy. If delinquency is at the origin of the classification, then much before the end of the loan, clients reach a certain maturity. It means that if they didn’t register delinquency before this maturity, it is highly probable that they won’t register any delinquency after. For bad loans, once the bad status is reached, it will remain with the borrower till the end of the loan. The profile of the subject: groups all the available information on the subject applying for a credit. This subject can be the person applying for a consumer loan, a business applying for a commercial loan or a micro borrower. At small business scale, the distinction between company and household is blurry, so the profiles of both have credit risk prediction power. We came to the conclusion that the profile of an applicant can accommodate five categories of characteristics: socio-demographic variables (for subjects where the person is at the center of the decision), business-demographic variables (for business subjects), financial data, product data and past credit behavior. The multivariate analysis: is at the essence of credit scoring. Different techniques are proposed and all techniques are empiric. This is the big advantage of credit scoring over judgmentalintuitive reasoning of the loan offices. The result is an algorithm. A scoring formula, a scorecard, a model – all these are algorithms. Since the use of the non-parametric techniques, the algorithm is the notion that resumes well the mechanisms at the core of credit scoring. The algorithm tells the user how to proceed to identify the forecasted class to which belongs an applicant. The accuracy of the forecast is also known. The algorithm also includes the precise rules of accepting or rejecting the applicant. In nonparametric algorithms the cutoff is predetermined, while in parametric algorithms the cutoff is set based on the score distribution. The cutoff indicates the estimated share of good and bad loans that will be accepted at the selected level. The use of credit scoring: is meant for the loan officer who does the calculations and follows the logical instruction of the algorithm, or for an expert system – software. Here the two important opportunities in cutting the cost of the transaction. First: simplify the task of the loan officer in the appraisal process and by consequence reduce the cost of appraisal and second: exclude the officer from the process. In microfinance, the exclusion of the loan officer seems so far impossible, since information which is qualitative and coming from informal sources has to be correctly collected and estimated. During the use of the credit scoring, its true performance is gradually revealed. The initial use of credit scoring is always delicate, since the effects on screening bad risks will be seen in several months or more. The characteristics of the population have to be measured also as these can indicate a possible change in the credit behavior habits of the borrowers. Recent developments in the area of credit scoring made possible the construction of algorithms that use the control ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 22 function to adjust gradually the algorithm to new changes in the population and to incorporate the knowledge obtained during the use of credit scoring. Ethics at the core of credit scoring: Durand (1941) when pioneering credit scoring used a discriminant statistical technique. The methodology was adapted by Fischer (1937) and subsequently employed in different areas including eugenics. Credit scoring was meant to discriminate. Is it ethical? The problem seems complex but the answers to the following questions may help. If costs limit extension of credit to small borrowers and if the fear of credit risk prohibits extension of credit due to severe information asymmetry, should scoring be kept away from microfinance? Should solidarity be always with the low-income borrowers in covering the high cost of losses? If a characteristic is a risk predictor, it will probably be considered during the judgment of the loan officers. It will also be considered by the credit scoring algorithm. If the direct use of the characteristic is prohibited, it will be probably used indirectly via other characteristics. The personality of the borrower is certainly very important but empirics are science. When the question is in the cost, a natural solution is credit scoring. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 23 Bibliography Altman, E. I. (1968). Financial Ratios, Discriminant Analysis and the Prediction of Corporate Bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 23. 589-609. Ang, J. S., Chua J. H. and Bowling C. H. (1979). The Profiles of Late-Paying Consumer Loan Borrowers: an Exploratory Study. Journal of Money, Credit & Banking (Ohio State University Press) 11, 222-226. Armendàriz, B. and Morduch, J. (2005). The economics of microfinance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Ashta, A. and Patel, J. (2010). Is SaaS the Appropriate Technology for Microfinance? CERMi research workshop, Mons. Boggess, W. P. (1967). Screen-test your credit risks. Harvard Business Review 45, 113-122. Capon, N. (1982). Credit Scoring Systems: a Critical Analysis. Journal of Marketing 46. Chapman, J. M. and Ass. (1940). Commercial Banks and Consumer Instalment Credit. National Bureau of Economic Research. D'Espallier, B., Guérin, I. and Mersland, R. (2009). Women and Repayment in Microfinance. CERMi Working paper. Durand, D. (1941). Risk Elements in Consumer Instalment Financing. National Bureau of Economic Research. Edmister, R. O. and Schlarbaum, G. G. (1974). Credit Policy in Lending Institutions. Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis. 9, 335-356. Eisenbeis, R. A. (1978). Problems in applying discriminant analysis in credit scoring models. Journal of Banking & Finance 2, 205-219. Ewert, D. C. (1968). Trade Credit Management: Selection of Accounts Receivable Using a Statistical Model. Journal of Finance 23, 891-892. Fair Isaac Corporation (2010). www.fico.com. Accessed on 30 April 2011. Holsapple, C. W., Tam, K. and Whinston, A. B. (1988). Adapting Expert System Technology to Financial Management. The Journal of the Financial Management Association 17, 12-22. Muchinsky, P. M. (1975). A Comparison of Three Analytic Techniques in Predicting Consumer Installment Credit Risk: Toward Understanding a Construct. Personnel Psychology 28, 511-524. Myers, J. H. and Forgy, E. W. (1963). Development of Numerical Credit Evaluation Systems. Journal of American Statistical Association 50, 797-806. ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 24 National Commission on Consumer Finance (1972). Consumer credit in the United States. Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office. Nevin, J. R. and Churchill, G. A. (1979). The Equal Credit Opportunity Act: An Evaluation. Journal of Marketing 43, 95-104. Orgler, Y. E. (1970). A Credit Scoring Model for Commercial Loans. Journal of Money, Credit & Banking (Ohio State University Press) 2, 435-445. Plummer, W. C. and Young, R. A. (1940). Sales Finance Companies and Their Credit Practices. National Bureau of Economic Research. Rhyne, E. and Christen R. P. (1999). Microfinance enters the Marketplace. USAID Microenterprise Publications. Schreiner, M. (2000). Credit Scoring for Microfinance: Can It Work? Journal of Microfinance 2, 105-118. Sexton Jr., D. E. (1975). Credit Riskiness of Low-Income Consumers. Advances in Consumer Research 2, 197 -202. Smith, P. F. (1964). Measuring Risk on Consumer Instalment Credit. Management Science 11. 327-340. Tabor, J. S. and Bowers, J. S. (1977). Factors Determining the Credits Worthiness of Low Income Consumers. Journal of Consumer Affairs 11, 43-52. U.S. Senate (1979). Credit card redlining: hearings before the Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, United States Senate… Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office. Viganò, L. (1993). A Credit Scoring Model for Development Banks: An African Case Study. Savings and Development, 17. Weingartner, H. M. (1966). Concepts and Utilization of Credit-Scoring Techniques. Banking 58, 51-54. Young, R. A. and Ass. (1940). Personal Finance Companies and Their Credit Practices. National Bureau of Economic Research ------------------The conceptual framework of credit scoring from its origins to microfinance by Bumacov and Ashta Page 25