lt23637-sup-0002-suppinfo

advertisement

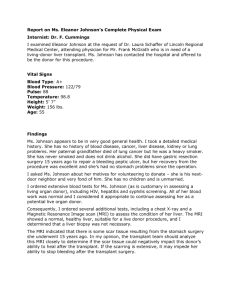

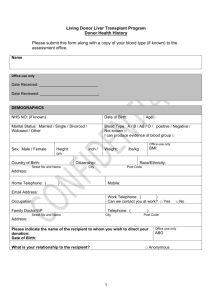

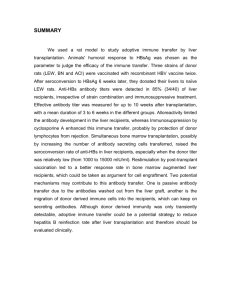

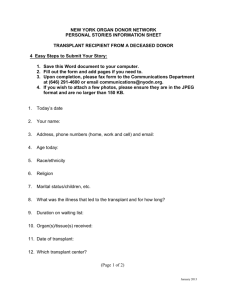

Communications Preparedness Plan Living Donor Liver Transplantation (LDLT) Program January 2012 Objective The purpose of this plan is to guide Cleveland Clinic’s communication response in the event of an adverse living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) outcome (specifically, the death of a healthy donor). The goal is timely, thorough and proactive internal and external communication to key stakeholder groups. Relevant Background Liver transplantation has been performed at Cleveland Clinic for more than 25 years, and our surgeons have been leaders in the development of LDLT. The Living Donor Liver Transplant Program exists to provide an option for patients with end stage liver disease. The impetus for this program remains the growing concern over increasing morbidity and mortality on the waiting list due to the relative scarcity of deceased donor livers. There have been several recent LDLT cases at other medical centers around the country that have resulted in donor death, and thus, leaders of the Cleveland Clinic LDLT program have decided to reevaluate their criteria, communications plan, and other elements of the program before proceeding with future cases. In addition, national data shows that one of every 200 LDLT procedures results in a donor fatality. Where some other centers have decided to discontinue offering LDLT, Cleveland Clinic is committed to continuing its LDLT program as we believe in the importance of offering patients this life-saving treatment, and we’re taking every step possible to ensure the safest and most effective treatment and optimal outcomes for recipients and donors alike. Cleveland Clinic’s Living Transplantation Program Cleveland Clinic celebrated 27 years of liver transplantation in 2011 since completing its first adult liver transplant on Nov. 8, 1984. Cleveland Clinic's liver transplant one-year survival rate for recipients of 90.9 percent exceeds the national average for expected survival rate. Our criteria for living liver donors has been developed based on our physicians’ collective experience, published research and outcomes data, and is in line with national guidelines set by the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS). Donors must be age 18-55; healthy (or with chronic conditions easily managed); suitable medical insurance; able to understand the risks; lack of coercion; family support; normal liver tests/scans (and biopsy, if BMI is more than 30); suitable anatomy; no or little previous surgery in upper abdomen; lack of significant steatosis; relationship or emotional tie to recipient (although altruistic donors are accepted). Incident Communication Process In the event of the fatality of a living donor, the following chart outlines the communications process that will occur to ensure appropriate information gets to all necessary audiences. This process should commence as soon as possible after the time of death and should be fully executed internally within 2-3 hours. External agencies should be notified on their required timelines. The Transplant Program Nurse Manager and the Transplantation Center Director should communicate regularly in the coming weeks with their contacts in Bioethics, Legal and Corporate Communications informed, especially as the team prepares required reports for external agencies. Spokespeople For media interviews, whether they are proactive or reactive, the following people have been identified as potential spokespeople. Depending on the outlet and the likely line of questioning, we suggest: Primary o Institute Chair o Director of Cleveland Clinic's Center for Ethics, Humanities, and Spiritual Care Secondary o Executive Director, Corporate Communication o Director of Clinical Ethics in the Department of Bioethics Other potential spokespeople: o Chairman of the Quality and Patient Safety Institute o UNOS: United Network for Organ Sharing (Richmond, Virginia; 804-782-4909) o OPO (Lifebanc, Cleveland; 888-558-5433) Potential Statement / Key Messages o The loss of a healthy person who bravely stepped forward to save the life of someone very sick is a tremendous loss, and we are deeply saddened by this news. o We believe in the importance of offering patients every safe and effective treatment option available to save their lives when they face a life-threatening condition, like liver failure. Living donor liver transplant has been a life-saving treatment for thousands of people around the world, but unfortunately, it is not without risks to both the donor and the recipient. o We consider educating potential living liver donors about the risks and complications of the procedure of paramount importance. We have a comprehensive program for screening, evaluating and educating potential donors to see if they are a good fit medically and to ensure they thoroughly comprehend the risks to them of their decision. o Patient safety is always our chief concern. We continually strive to minimize risk to our living liver donors, and in light of this loss, we will review our policies and procedures to see if any changes should be made moving forward. We will continue to take every step possible to ensure the safest and most effective treatment and optimal outcomes for recipients and donors alike. Next Steps o o o Decide on pursuing proactive media strategy for LDLT Media train necessary spokespeople Ensure we have the most up-to-date criteria APPENDICES Liver Transplant Background When liver failure occurs, a transplant is often the best option for long-term health. A patient can receive a liver transplant from a living or deceased (cadaver) donor. There is a shortage of deceased donor organs available, however. As a result, the number of patients on the transplant waiting list continues to grow. Patients waiting for a liver may die on the waiting list or become too sick to have a transplant. If a patient can receive a portion of a liver from a living family member or friend, he or she doesn’t have to wait for an organ. There are significant advantages and risks associated with living donor liver transplantation, however. LDLT involves transplanting only a section of the liver from a donor. The portion taken from the donor will regenerate over time in both the donor and the recipient, allowing both donor and recipient to survive for many years after the procedure in most cases. Regeneration of the liver occurs over a very short period: possibly days to weeks, and certainly within six to eight weeks. One large benefit to LDLT is that the transplant can be scheduled electively. It is also possible that the quality of the liver may be better, as living donors as usually young, healthy adults who have undergone a thorough medical evaluation over several days or weeks. Also, due to procedures on the donor and recipients occur at the same time, preservation time (when the liver is without blood) is minimal - minutes, not hours. In a typical LDLT, about 40-60 percent of the donor’s liver is removed. The anatomical division between the lobes permits surgeons to divide the liver into two distinct parts, which can function independently of each other. The right lobe comprises approximately 60 percent of the total liver volume, and the left lobe comprises approximately 40 percent. During the surgery, the donor’s gallbladder is also removed. When the recipient is a small child, a piece of the donors’ left lobe is removed. Adult-to-adult living liver transplants usually require the removal of the larger right lobe. The risk to the living donor is much higher with a right lobe donation. During a five-center survey in Asia (which is the area of the world with the most living donor liver transplants) reporting on 1,508 living liver transplants between January 1990 and December 2001 [766 adults, 742 children], it was reported that the complication rate was higher in right lobe (28%) than in left lateral segment (9.3%) or left lobe (7.5%) donors. For adult-to-adult transplants, Cleveland Clinic’s living donor liver transplant program will use the right lobe only when the left lobes is too small or anatomically unsuitable. . Charles Miller, M.D., Director of the Liver Transplantation Program, has published on the right vs. left lobe issue for living donor liver transplantation. His paper from 2006 said: “in terms of both morbidity and mortality, right lobectomy is riskier than left lobectomy. To the authors’ knowledge, there have been 12 deaths of right-lobe donors and three deaths of left-lobe donors worldwide.” Transplantation information In the United States, approximately 16,000 people are waiting for a liver transplant and only 6,100 deceased donor livers become available each year. Living liver donation can increase the existing organ supply. Other benefits include being able to plan for and schedule the surgery while the recipient is in optimal medical condition, better tissue matches, a decreased risk of organ rejection and the positive psychological benefits experienced by the donor who knows that he/she has made a life-saving contribution to the recipient. In general, only about 15 percent of those potential donors evaluated are actually accepted as candidates for live donor donation once they undergo evaluation. Donor complications (which occur during 15-30 percent of procedures) include: pain, bleeding which could require blood transfusions, blood vessel complications such as blood clots, neurologic complications such as a stroke, infection and bile duct leaks and srictures. The risk of death is between 1-in-10,000 to 5-in-1,000 depending on the lobe or segment donated. Most problems occur when right lobe is used, including death, organ failure, bleeding, liver failure, sepsis. (Risk is to donor when right lobe is used for transplant; when left lobe is used for transplant, majority of problems occur with recipient.)