Borrowing from Collectors – Word document

advertisement

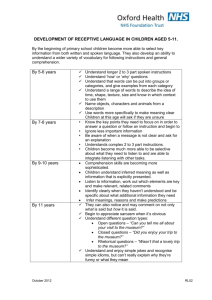

Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) Ann Eatwell ‘The Loan Court still contains certain important loans occupying in each instance a number of cases with more or less similar objects. But I have always felt that the whole policy of extensive loans belongs rather to the earlier stages in a museum’s history, and of late years we have been extremely chary of accepting fresh loans except in cases where the loan was believed to be a preliminary stage towards a gift or bequest.’ 2 In 1932, apparently responding to the need for greater space for the permanent collections, the Director of the V&A, Sir Eric Maclagan, circulated a memorandum, which suggested disbanding the dedicated loans gallery. He stated that seeking loans was a phenomenon common to the first phase in a museum’s history. Judging by the experience of the V&A that statement would appear to be true. Loans had held a central position in the Museum’s display strategy for the first eighty years of its existence. However, none of the public bodies set up as repositories of art and antiquities in England before this Museum appear to have had an interest in loans. In the early years of the British Museum (1753), the National Gallery (1824) and the Museum of Practical Geology (1835) purchase, gift and bequest were almost exclusively the sources of display material growth. The only loan held by the British Museum throughout the nineteenth century was the Portland Va se. 3 The institutionalising of a public system for loans from collectors must be considered to be the innovation of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Recent publications which specifically discuss the role of the V&A and its impact on the art world have largely ignored this innovation. 4 The nature of the subject appears to be naturally elusive due to the perceived difficulty of reconstructing the type and pattern of loaned material but good records do exist. These give facts and figures which can reveal t he scale of the activity. From the late 1860s to the early 1880s, in numerical terms, loans consistently accounted for about one third of the gallery displays of the art collections 5 . In 1879, the largest number of loan items was recorded at 18,866 from 4 37 lenders at a time when the Museum owned only 30,441 objects. 6 Furthermore, some of these acquisitions would have spent lengthy periods of time away from the Museum. In 1871 over 4,000 objects were lent out to schools of art and colleges, considerably r educing the number of art objects owned by the Museum that would have been on view at any given period. The scheme of lending from the institution was, with the encouragement of loans in, part of the same plan of the early administrators to expand their ac tivities and influence beyond the physical confines of the actual museum building. They also hoped to spread their own ideas for creating lively displays, by promoting local lending at regional centres, to assist in the formation of museums 7 . Archive documents can also provide details of the collectors and the objects on loan. In some cases photographs of loans exist and records can help identify which loans became gifts, bequests or purchases. There is plenty of material evidence that loans and their lenders helped to create the collections of the V&A. 8 The historical significance of the loaning process which determined the perception of the Museum as well as its collections must be explored to understand how the institution evolved, the full range of it s influence and how it differed from comparable organisations. Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG The addition of loans to the newly opened rooms at Marlborough House, which were lent to the Department of Practical Art to accommodate the Museum and Government School of Design, was the first stage of the innovatory process. Borrowing from his friends amongst the growing fraternity of collectors, dealers and manufacturers interested in historic art objects, Henry Cole, the first Director, (fig. 2) used loans to round out the small collection which formed the nucleus of the Museum. This core group consisted of purchases from the Great Exhibition and the material that had been used for teaching by the Government School of Design. The first displays were largely of modern manufacture and Cole im mediately set about borrowing old to add to the new. In 1852, the Queen lent 44 pieces of eighteenth century Sevres porcelain, the manufacturer, Herbert Minton lent 49 items of European and Chinese pottery and porcelain from his factory museum. Other signi ficant lenders were Prince Albert lending four German paintings on porcelain (including one described as “a picture by Sir Edwin Landseer, made in Bavaria”), the dealer John Webb (wood carvings, oriental porcelain, Sevres, Worcester porcelain and delft) an d wealthy philanthropist and collector Miss Burdett Coutts who lent two Chelsea porcelain vases. 9 The change in the appearance of the Museum, which began to resemble a collector’s cabinet, and the effect of the loaning policy was noted in the Athenaeum. “ The principle of borrowing for temporary exhibition the fine works of Art and virtu so profusely scattered throughout the rich mansions of our nobility, has been eminently successful; constituting one of the most valuable features of the institution – a constant succession of novelties.” 1 0 Until J.C. Robinson was appointed as the first curator in 1853, Cole who was an able and energetic administrator but no connoisseur, relied upon the advice of his more knowledgeable friends for the acquisition of loan s and more permanent additions to the collections. Apart from confirming the primary importance of loans 1 1 and recommending that objects be loaned to the Museum before purchase, Cole has left us no policy statements on the issue of loans. Robinson was mor e forthcoming. Robinson and Cole did not have an easy relationship and fell out over many matters of Museum practice but the idea of loans was supported very vigorously by Robinson. As early as 1854, he published a paper in which he emphasised the importan ce that the use of loans was felt to play in the new institution’s strategy. “Finally, I would refer to the example already so successfully set by the Department in the institution of special exhibitions, got together by means of loans from private collec tors, and the practice, now well established, of adding to the attractions of the permanent collections by this means. ” 1 2 Later in his life, he confirmed that the initiative to encourage lending as a matter of policy was an innovation of the early Museum. He listed what he described as “The principal extensions of the actions of Museums brought about by South Kensington” beginning with the various types of lending to the Museum but not forgetting the lending from the Museum by circulating exhibition to Art Schools and Provincial Museums. The following quotation comes from an article by J.C. Robinson published in The Nineteenth Century in 1880: “the essentially modern idea of temporary exhibitions, that of gathering together works of art and general interest, on loan, taken hold of from the first at South Kensington, has fructified and expanded to an extent, the importance of which it is impossible to overrate. In addition to the formation from time to time of special exhibitions, practically it has been found possible to supplement and illustrate the permanent art treasures of the State by a standing collection, though composed of fluctuating and varying matter…...In this way the enormous accumulation of works of art of all kinds, in the possession of the Crown, of corporations, and societies, the ancestral gatherings of the nobles and gentry of the land, and the rich collections of amateurs and connoisseurs, are made available for the delight and instruction of everybody.” 1 3 Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG Although Robinson did much to champion loans while he worked for the Museum, the credit for the pioneering of this activity must go to Henry Cole. He would have been familiar with the limited lending which took place in the late 1840s, from the small collections of the Government School of Design to provincial establishments. He was comfortable with the concept and practice of temporary exhibitions from the small scale of those of the Society of Arts to the vast scale of the Great Exhibition of 1851. Crucially, he had also been respon sible for the organisation of the first exhibition of historic decorative art for the Royal Society of Arts in 1850. 1 4 The intention of the exhibition, as expressed in the catalogue, was to educate the taste of the public and manufacturers for the product ion and consumption of well designed modern goods rather than promoting antiquarianism. Cole’s use of loaned material in the Museum was begun with the same purpose in mind. The experience of this first exhibition of applied art would have taught Cole how t o deal with collectors and he would have begun to appreciate the value of these wealthy and influential men (and a few women) as well as the potential of their objects. Certainly the lenders to the exhibition were in due course called upon to lend to the Museum. Sir Anthony Rothschild and Hollingsworth Magniac (who had been on the committee) lent furniture to a display of cabinet work at Gore House in 1853 which formed the first temporary exhibition held by the Museum. Even A.W. Franks, the secretary of the exhibition committee, who had joined the staff of the British Museum in 1851, lent ceramics; Persian, Chinese, and British, “vase, old Staffordshire agate ware ” and a “ piece of enamelled earthenware frieze, by Luca della Robbia”. 1 5 What did the Museum gain from being a pioneer in the practice of temporary loans? The obvious answer of objects is actually more complex than one might imagine. Certainly in the early years, Cole needed to fill the exhibition spaces at Marlborough House to try and justify, through adequate and relevant material, the status of the new Museum. The British Museum which was founded with enormous collections of its own did not have this problem. Cole’s new Museum had to compete as quickly as possible on equal terms with the existin g museums and galleries and borrowing on a large scale was one way of achieving this. Later, Cole was to use the pressure of loaned material to claim more space at South Kensington. Loans and special exhibitions could spread the territory of the ornamental collections and they added to the attractions of the permanent displays. Cole would have realised that he could not hope to acquire a large number of objects through Government funded purchase. Money was always tight. The cost of buying the objects was in creasing as the competition rose amongst collectors and institutions to secure examples from the shrinking supply. For a new museum short of material, the best option apart from borrowing, was to buy ready assembled collections with good provenance from c ollectors who had an established track record. Cole had some success with this policy. He acquired the Bandinel collection of over 700 pieces of historic ceramics for the paltry sum of £250 in 1853. However, in 1855 the important collection of mainly Frenc h and Italian Renaissance art owned by a Parisian lawyer, Jules Soulages was brought to Cole’s attention by Herbert Minton 1 6 . A price of £ 11,000 for the 749 objects was agreed but the Government refused to pay. Cole raised a subscription for the collections’ purchase, brought it to England and displayed it at Marlborough House for two months from December 1856. Over 48,000 visitors attested to the public’s interest in the objects. It was sold to the committee organising the Manchester Art Treasures exhib ition in 1857. Only after this exhibition did Cole finally arrange for the Soulages Collection to be bought for the Museum in instalments. (fig. 3) The last of these was not paid until 1865. Loans must have seemed a better option when money for acquisition s was not forthcoming. Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG Loans were also flexible, not only in the sense that they could be expanded or contracted as a type but from the variety of objects that could be borrowed. This was a bonus at a time when the study of the decorative arts was in its infancy and potentially costly mistakes in attribution that might result from a careless purchase could be avoided. It was far easier to borrow and display objects that could be returned should advances in the study of the subject diminish the importance of the items. The rapidly evolving nature of the interest in and knowledge about the historic decorative arts at the time of the Museum’s foundation did indeed present Henry Cole with a credibility gap in terms of becoming the first Museum of a newly create d subject. A similar dilemma may have been at work at the British Museum which did not start to collect in the area on any scale until the mid -1850s under A.W. Franks. The teapots, vases, bowls, ornamental figures and dinnerware which had been used by the previous generation, had only just begun to acquire a new status as art objects. A market for such material began in earnest in the first half of the nineteenth century and collectors like Alexandre Du Sommerard (1779 1842) and the lawyer, Jules Soulages in France and William Beckford (1760 -1844 ), Ralph Bernal M.P. (c.1783-1854 ), civil servant James Bandinel and the jeweller and silversmith, Joseph Mayer in England, amassed some of the earliest significant collections. These were accrued without the assistance of authoritative publications or exhibitions. In the 1850s and 1860s publications had begun to appear and exhibitions such as that held at the Society of Arts in 1850 and the Manchester Art Treasures exhibition of 1857 increased the understanding of the subject and promoted its legitimacy within the hierarchy of the arts and in polite society. Cole, of course, had through the careful manipulation of the loan system always had the advantage that the status of his lenders alone bestowed credibility to the objects lent. The lenders themselves were almost as important to the Museum as their objects in terms of prestige, in assisting with the authentication of taste and as a magnet to draw the public in. People wanted to come and look at what the celebrit ies of their society owned. Although loaned objects were dispersed amongst the collections at Marlborough House, the status and identity of the lender had a real importance and lenders were named on the labels accompanying their objects. “ The pieces belo nging to Her Majesty have been distinguished by a crown placed above the numbers.”. 1 7 There was also a strong perception that in England, as opposed to the continent, the wealth of the nation was hidden from view in the great houses of the country. De Quincy wrote in 1796, shortly after the opening of the Louvre; “ England has no centralised, dominant collection despite all the acquisitions made by its private citizens who have naturally retained them for their private enjoyment. What is the result? These riches are scattered through every country house: you have to travel through every county over hundreds of miles to see these fragmented collections….” 1 8 By putting these treasures on show and by encouraging lenders to come forward in great numbers to ta ke part in a scheme for the benefit of the nation, Cole was winning a great public relations victory for the Museum. The same idea of unlocking private collections became one of the aims of the first club for collectors of the historic applied arts which Robinson dreamed up and started with the assistance of the sculptor, Baron Charles Marochetti and the Sardinian Minister, Marchese d’Azeglio in 1857. 1 9 Robinson would have needed the support of Cole, his superior, in order to use the resources of the Muse um to run the club. The advantages of such an idea to the Museum must have been obvious to both men. The association would allow closer ties to form between the Museum, its staff and collectors, creating a community of art -loving connoisseurs who would pursue the Museum’s interests. For example, collectors could be encouraged to collect to fill the gaps in the public collections. There were other less obvious but significant advantages. The move to South Kensington in 1857 gave the Museum greater potential for expansion but with the knowledge about the objects which might be acquired still evolving it was able to call on knowledgeable collectors through the club contacts for Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG supplementary advice. 2 0 The dialogue between collectors and Museum had many direc t benefits. For example in the Museum’s report to the Government for 1865 the assistance of collectors in revising the art inventory was highlighted. Some, such as C.D. Fortnum, even wrote authoritative official publications. 2 1 Their wider influence on the creation of an identity for the Museum has yet to be fully explored. The original club membership of ninety connoisseurs, collectors and curators grew to over two hundred by 1860 and links with the Museum were strengthened by the evening conversazione that were held on the premises, by member’s loans, but most especially by the Special Loan Exhibition of 1862. This was to be the club’s finest hour. Organised by J.C. Robinson with members serving on the committee and lending generously (between nine and ten thousand items from five hundred and fifty -three lenders) the exhibition was a huge popular and commercial success. There were almost nine hundred thousand visitors to the displays of historic material which rivalled the attendance at the International E xhibition of modern manufactures that took place at the same time. The exhibition became a respectable provenance for objects through the enhancing effect of the credibility of the collectors and curators involved in the selection process. An annotated cop y of the original catalogue in the National Art Library reveals that a number of items are now in the Museum’s collection. Some objects were acquired as gifts soon after, and as a result of the exhibition, while others passed through the possession of several collectors. For example a Limoges painted enamel tablet was shown by the Duke of Hamilton, sold at the Hamilton Palace sale in 1882, bought by George Salting and bequeathed to the Museum with his collection in 1910. 2 2 Apart from starting a club for co llectors, the Museum encouraged the lenders support by a variety of other means. Lenders were sometimes paid to display. This often took the form of a percentage, described as a rental in the official documents, of the agreed value of the items lent. It was partly a ruse to secure objects prior to purchase although it was also a means of paying dealers and less wealthy collectors for the loan of their objects. A document in the archives of the Museum (now at the Archive of Art and Design, Blythe House) give s an insight into the official dealings with collectors. In 1867 an administrator wrote: “ It was proposed that Mr Webb’s Greek glass should be hired for one year at 5% on £1705. This was approved by the Duke of Marlborough.” 2 3 The lending of objects be fore acquisition was also a pragmatic attempt by Cole to wrest money from the government. By demonstrating the interest taken in some of the loans he could summon more support for his purchasing plans. The Gherardini collection of models in wax and terraco tta was exhibited for a month to test the waters and then acquired. 2 4 The prominent position of loans within the Museum displays would have formed a major incentive for lenders who welcomed exposure for themselves and their objects. 2 5 Although at Marlborough House and in the early years at South Kensington, loans were displayed in the same rooms as the Museum’s collections, with the completion of the North and South Courts, large and grandly decorated spaces had become available for differentiated display s. (fig. 4) As early as 1856, Robinson had advocated a policy of privileging loans. “ It is, however, greatly to be desired that the system of loans should be continued, and indeed in every respect more completely developed: with this view I would sugges t, that when increased space can be obtained, a distinct area with the requisite fittings should be set apart for objects exhibited on this footing, so that they should no longer be placed in indiscriminate juxta-position with permanently acquired specimen s.” 2 6 An exhibition of loaned material opened the North Court and the Special Loan Exhibition of 1862 was the first display in the South Court (now an exhibition space). By 1871, the Museum had 18,302 objects of its own but 10,026 on loan with the number of lenders each year averaging about 400 during the next 15 years. With over a third of the exhibits from lenders, the numerical dominance of loans, apart from the importance of the objects and the status of Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG their owners, must have encouraged the Museum a uthorities to seek special display solutions. A series of guides produced for the public in the late 1860s give a detailed account of the displays which, with the few surviving contemporary photographs, give some idea of how the Loan court must have looked. Objects were grouped according to the lender, rather then by material, as in the main collections. A collection might merit several cases. “ A large and varied collection of Italian Porcelain of the eighteenth century, belonging to the Marquess d’Azeglio, the Italian ambassador in England, fills three cases.” 2 7 Lending to the Museum could be seen at this time as rather fashionable in certain circles and the list of lenders encompassed some of the leading figures in Victorian society from wealthy connoiss eurs such as Lady Charlotte Schrieber, (a collection of English pottery and porcelain, from 1866 -1873) to busy politicians like W.E. Gladstone (ceramics in 1867, jewellery in 1871, ivories in 1875). An alphabetical list of lenders in 1874 occupied eleven pages and included, the Queen, the Prince of Wales, Lords and Ladies, Viscounts and countesses, officers, clergymen, collectors, dealers, designers and manufacturers. Women lenders made up a greater proportion of the total than might be expected. The mater ial lent was diverse but largely followed the areas of interest in the applied arts formulated by the Museum. 2 8 Entire collections of objects from individual collectors swelled the numbers and spread the displays to other parts of the Museum complex. C aptain A.W.H. Meyrick loaned an important collection of arms and armour assembled by his cousin Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick (1783 -1848) from 1868-71. This was shown in the exhibition galleries which stood on the site of the Science Museum. The dealer Isaac Fal cke lent 921 pieces including ivories, bronzes, Chinese and European ceramics, particularly Wedgwood. 2 9 This collection was displayed at Bethnal Green in 1875. The principal loan of 1878 was the Schliemann collection of 4,420 items, excavated in Turkey an d believed to come from Troy, with drawings and photos. Though perhaps more appropriate to the British Museum, since it did not mount temporary exhibitions, the collection could not be shown there. 3 0 Loans continued to occupy their own distinct area within the South Court until the end of the century and for many years, its position, at the entrance to the Museum, provided a conspicuous arena for loan display. Another repository for loans became the new out station at Bethnal Green which opened in 1872. A. W. Franks’ collection of Oriental porcelain was shown here from 1876 -1884 and Sir Richard Wallace’s pictures and furniture were displayed at this museum for three years while Hertford House was being prepared. From 1909, the loans continued to be privilege d, in terms of space and location in Sir Aston Webb’s large, newly built octagon shaped court which became known as the Loan Court (now the costume gallery). Great care was taken over the well being of the loans. A Board of Education report of 1912 -13 recorded that the ceramics galleries, the Salting Bequest and the Loan Court had been closed for some time because of fears of attack from suffragettes. Loans remained in the court until 1932 when Maclagan proposed that loans be restricted and re-integrated in the permanent collections. The wealth of documentation about loans, which the Museum produced, would have convinced a lender that the scheme was taken very seriously by the officials. From the first government report of 1853, loans were discussed in an in dividual section and from 1870 separate reports on loans were issued every year until the late 1880s when they became less frequent. The facts and figures reveal the number of objects on loan, the names of the lenders, with detailed label information on ea ch new loan displayed in that year. Registers of lenders give names, addresses and dates of loans entering and leaving the Museum. Loans had reached their maximum level in 1879 of over 18,000 objects but in the same year the Museum only acquired twenty pieces of silversmiths’ work at a cost of £362. This was a good year for silver. Sometimes only one object was acquired. Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG It is, therefore, easy to see why loans were particularly important to the Museum’s displays of silver. The collection remained small thr oughout the nineteenth century and was not at all comprehensive. The bias towards ornamental German pieces of the heavily embossed type and sixteenth century Spanish silver reflected Robinson’s own inclinations. The foundations of the important collection of English silver was laid in spite of him. Robinson was known to have a distaste for what he termed ‘merely usable plate’ which he said could not be considered as art nor did he appreciate goldsmiths work of a later period than the 17th century. Although the collecting of English plate was already established and knowledge of the subject disseminated by the antiquary Octavius Morgan and the dealer William Chaffers, Robinson was prevented by his prejudice from taking advantage of the published work in this field. In 1864, the Museum was offered the Sterne Cup but Robinson condemned the purchase as not being an example of art. In his report he added ‘I think it extremely unlikely that so common a specimen of usable English plate could ever have been a Royal gift.’ The Museum finally bought it in 1925. Cole, aided and abetted by William Chaffers did occasionally manage to buy a worthwhile piece. A chinoiserie sugar -box entered the collection in 1865. Robinson left the Museum in 1867 and was replaced as Art Ref eree by Sir Matthew Digby Wyatt who had excellent paper qualifications but no eye. His principal aim was to find the Museum bargains rather than stars. After his death in 1877, Sir Wilfred Cripps, a leading authority on English plate was appointed and a mo re promising era for the silver collections ensued with important purchases such as the Mostyn plate and bequests of the significance of the Calverley toilet service. With the Museum under greater pressure to provide a more comprehensive display of the decorative arts as information improved and the public’s appetite grew, loans were the obvious answer. Acquisitions in ceramics had largely followed the fashionable preference for Italian maiolica, Hispano Moresque ware, Sèvres and other continental porcel ains. The Museum’s collection of English pottery and porcelain was small and unfavourably compared by critics with those at the Museum of Practical Geology and in regional museums. Sir Arthur Church (1834-1915) who became an advisor for the ceramic collect ions and was the author of two of the South Kensington Handbooks on English Pottery and Porcelain, wrote to the President of the Science and Art Department in 1881 deploring the inadequate representation of English ceramics. In the 1860s and 1870s a large number of collectors including Henry Willett, Mrs Palliser and especially Lady Charlotte Schreiber and her husband Charles contributed to improving the displays. The Schreibers lent 224 pieces of English porcelain from 1869 -73, many of which were later to form part of the Schreiber gift. 3 1 In terms of silver, important loans in the nineteenth century were the continental collection lent by G. Moffatt in 1863, the 320 pieces of largely English silver of J. Dunn Gardner (from 1870 -1901) and the Bond Collection. Joseph Bond first lent to the Museum in 1865 and in 1884 lent largely neo classical silver which became a bequest. Loans now make up a tiny proportion of the Museum’s permanent collections of almost 4 1 / 2 million objects with just over 4,000 objects f rom over 500 lenders. The Metalwork Department has the largest number of lenders, currently 140 who lend 819 objects in total. This is in part due to the large loan collection of church plate, the result of a conscious effort by the Museum authorities to increase their collections of this type of material and to provide a safe repository for an important part of the country’s heritage that they thought was at risk. A circular to that effect was drafted in 1917 after consultation with senior figures in the church. It had the effect not only of increasing the displays in the Museum but also of stimulating the clergy to make inventories of their plate and to consider how it should be cared for if it was no longer in use. Some of the Museum’s loans reflect the long and mutually beneficial association between the institution and the lenders and their families. The Raphael cartoons have been on loan from the Queen since 1865 while the Outram Shield, made in 1862 -3, and designed by Armstead for Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG Hunt and Roskell with scenes from Sir James Outram’s career in India, was first lent by the family to the Museum in 1864. It has been redisplayed this year in the Museum’s newly opened gallery Silver 1800-2000. (fig. 5) But long term lending was never the aim of either the Mu seum or its lenders. Most of the loans were short term and lasted for two or three years at most. Quite often the lender maintained a continuing relationship with the Museum by changing the objects on loan or lending to a specific temporary exhibition such as the special loan exhibition of Spanish and Portuguese Ornamental Art in 1881. Sir Richard Wallace and Lady Charlotte Schreiber were both lenders to this exhibition. (fig. 1). Ultimately, the Museum hoped to fill gaps in the collections through lenders generosity. The large and exemplary collection of English pottery, porcelain and enamels amounting to nearly 2,000 pieces donated by Lady Charlotte Schreiber was one of the most important gifts the Museum received in the nineteenth century. George Salting’s bequest of Renaissance and Medieval art, on loan from 1874, was a further example of a lender who became a significant donor. These symbiotic relationships continue to this day. In the Metalwork Department, one of the most recent conversions from a loan was the collection of Victor Morley Lawson. For over twenty years Morley Lawson collected English silver, from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth century, with the guidance of the Museum’s staff. His collection was lent to the Museum from 1968 un til his death in 1988 when the Commissioners from the Inland Revenue accepted his collection in lieu of tax and allocated a small group of important pieces to the Museum. The character of the V&A today; the shape of its collections, the continuing temporar y loan exhibitions and the close relationship with specialist societies, reflect the experiments by Cole and Robinson in the 1850s which became practice and policy. Borrowing from collectors was an important element in those early plans, which survives to this day, and it is interesting to see that the number of lenders is almost identical to that of the heyday of lending in the 1870s and 1880s. The activity has a much lower profile in the displays today, but in the past, it provided a stimulating and ever changing environment through the Loans Court, the large individual loans and the special exhibitions. “There is always something new in the Museum, and if this lead(s) to such constant change in the arrangements that it is sometimes difficult to find what is wanted, it has the advantage of assuring visitors that they can scarcely go too often.” 3 2 This populist approach, where lenders and visitors appear to be privileged above the objects, in terms of display, had its critics who complained that the collec tions gathered in South Kensington were too diverse and not focused enough. Others felt that the Museum could no longer fulfil its objective by providing clear models for designers and workmen. Despite this criticism and the deliberations of the Committee of Rearrangement in 1908, which led to a re-evaluation and change in the method of displaying the accessioned collections, the Loan Court remained a separate and vital area for many years. Some curators were in no doubt of the value of establishing good li nks with collectors, to which the lending activity had contributed. Writing of the formation of the ceramics collection in 1957, Arthur Lane commented; “ The collection has taken just over a hundred years to form. A great deal of intelligence has been exercised on it, and a great deal of money spent. But comparatively little of either the intelligence or the money was provided by the Museum staff or their masters at the Treasury. Indeed one has only to look attentively at the labels in case after case to recognise that the real builders of the collection have been the private citizens who chose to put their experience and resources at the disposal of the Nation.” 3 3 Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG Ann Eatwell is an Assistant Curator in the Metalwork Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Her most recent project has been the successful completion of the second phase of the Silver Galleries at the V&A. She has published widely in the field of ceramic history and collecting history, including Susie Cooper Productions (1987), the metalwork chapter, cowritten with Tony North, in Pugin, a Gothic Passion (1994) and contributed a number of sections in the V&A publication accompanying the new silver gallery, Silver (1996) edited by Phillipa Glanville. NOTES 1. This article is based on a paper given at a sessi on organised by C live Wainwright on the history of the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museu m at the Art Historians conference in 1995. I shou ld like t o thank Anthony Burton and Elizab eth James for their help with this paper. 2. Sir Eric Maclagan’s m emorandum, January,1932 ( Ed 84/114 Minutes of the Ad visory Council ) quoted in John Ph ysick, The Victoria and Albert Museum, The History of its Building , London, 1982, p.267 -8. 3. It was not until 1911 that a Board of Education r eport noted that French Museums were beginning to explore the idea of loans. Board of Education Report for the Year 1909 on the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Bethnal Green Museum, 1911, p. 15. 4. Malcolm Baker and Brenda Richardson ( eds ), A Grand Design: The Art of the Victoria and Albert Museum , New York and Baltimore, 1998 and Anthon y Burton , Vision and Accident, The Story of the Victoria and Albert Museum , London, 1999. 5. The South Kensington site was also hom e to a number of other misc ellaneou s collecti ons including the Patent Museum, the Educational Museum and the Food Museum. E ven C ole desc ribed the venture as a “refuge for d estitute collections”. From 1872, loans were a ls o shown at the Bethnal Green Museum. 6. The tota l for Museum acquisit ions has been ca lculated t ogether from fi gures supplied in c ontempora ry reports and inventori es. 7. J.C. Robinson, Catalogue of the Circulating Collection of Works of Art , London, July 1860. For example, the Museum of Sci ence and Art, Edinburgh, founded in 1854 followed the V&A m odel in encouraging individual local lenders as the su rviving Loan Regist ers att est. 8. A recent survey of the peri od contextualis es th e importance of c ollectors for th e V&A. “ Few National Museums, indeed can have had such an in timate and mutually influential relationship with the community of c ollectors that help ed sustain it. ” Arthur MacGregor, “ Collectors, C onnoisseurs and Curators in the Victorian Age ”, A.W. F ranks Nineteenth Century Collecting and the British Museum , edit ed by Marjorie Ca ygi ll and John Cherry, London,1997, p.26. 9. A Catalogue of the Museum of Ornamental Art , 5th Edition, May 1853. John Webb, a retired Bond Street dealer as sisted Cole with his early purchases and loans of historic objects. He remained a fri end of the Museum until his death in 1880 and a purchase fund left b y him continues his association. 10. Athenaeum, 1st October, 1853, p.1162. 11. “The rec eption of obj ects on loan, from th e first a recognised action of the d epartmen t …” Henry Cole, Eleventh Science and Art Department Report , 1864, p.xiii. 12. J.C. Robinson, An Introductory Lecture on the Museum of Ornamental Art of the Department , Board of Trad e, Departm ent of Sci ence and Art , London, 1854, p.29 -30. 13. J.C. Robinson, Our National Art C ollections and Provincial Art Museums, The Nineteenth Century , June 1880, p.990 -991. 14. Catalogue of Works of Ancient and Medieval Art, Exhibited at the Hous e of the Societ y of Arts, London,1850. 15. First Report of the Department of Science and Art , Lond on, 1854, p.285. See als o Aileen Da ws on, Franks and European Ceramics, Glass and Enamels, p. 201& 216, A.W. Franks, Nineteenth -Century Collecting and The British Museum, edited by Marjori e Caygi ll and John Cherry. Da ws on speculat es that a fri eze b y Della R obbia shown at the exhibition in 1850 may have been bequeathed to th e British Museum by Franks in 1897. It ma y be th e sam e piec e shown by Franks at Marlborough Hous e in 1853. 16. Ann Eatwell, Henry Cole a nd Herbert Minton: Collecting for th e Nation, Journal of the Northern Ceramic Society , Vol. 12, 1995,p.151 -174. 17. First Report of the Department of Science and Art , London, 1854, p.289 18. Quatrem ere d e Quincy, quot ed from the translation in Francis Haskell, The British as Collectors, The Treasure Houses of Britain. Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Art Collecting , National Ga llery of Art, Washington, DC, 1985, p.50. 19. Ann Eat well, The Collect ors ’ or Fine Arts Club 1857 -1874: The First Societ y for Collectors of the Dec orative Arts, Journal of the Decorative Arts Society , 18, 1994 p. 25 -30. 20. While Robinson provided exp ertis e of a high standard over many areas of th e collection, he had som e notable blind spots, of which silver wa s one. Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG 21. A fri end of Cole and financially independent, For tnum travelled through Europ e and the near East acquiring objects for the Museum and writing two catalogu es; Maiolica (1873) and Bronzes of Europea n Origin (1876). 22. George Sa lting, a wealth y c onnoisseur c ollect ed single mi ndedly for man y yea rs. His ba ch elor apartment was sma ll and he lent his growing collection of ori ental p orc elain, and medieval and Renaissance a rt to th e South Kensington Museum from 1874. 23. E.D. 84/414 Loans to the Museum, Statement showing proc edure, regulations etc from the year 1 861. The Duke of Marlborough was a Governm en t minister at the time. 24. Second Report of the Department of Practical Art , 1854, p.178 -85. 25. Other advantages for collectors and dealers loaning to museums, such as the financial incentives of safe, cheap storage and an improved provenance for loans that are la ter s old, seem not to have been the factors dri ving the relationship of collect ors and the Museum in the 19th century. While rec ognis ed as important in the 20th century, there are few referenc es to th ese c onsiderations in the Museum’s early years. Anthon y Burton quotes on e reference in Vision and Accident , p. 124. The critical maga zine Truth lambasted the Museum’s rea diness to offer aristocratic owners a “ a safe and inexpensive resting -plac e for their t rea sures.” 26. Third Report of the Department of Science and Art , 1856, p. 68 -9. I am grat efu l t o E liza beth James for dra wing m y attention to this. 27. A Guide to the Art Collections of the South Kensington Museum , London, 1868, p.16. 28. Wom en accounted for 68 of the names on the list of 407. List of Objects in the Art Division, South Kensington Museum, Lent during the year 1873 , London, 1874. 29. A collection of 500 pieces of Wed gwood was given to the British Museum by Isaac Fa lck e in 1909. 30. The justification for showin g som e of the groups of loans; such as the Schliemann collection; or the Pitt Rivers collection of anthropology (exhibited at Bethnal Green from 1873 before transfer to South Kensington prior to the opening of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford in 1885) within the context of an Art Collection ma y s eem untenable now but were p erhaps attempts to offer the broad est perspective of art and design to the new audience. Indeed Cole had praised the design of African objects at a Missionary exhib ition in Manchester in the 1870s. 31. A. W. Franks recomm ended that Lad y Charlotte Schreiber give her collection of 2,000 piec es of English pottery, porcelain and enamels to th e V&A. However, h e was d eterred from pres enting a collection of continental porc elain of his own b y “ disparaging rema rks ” made b y the Museum staff about the Schreib er gift. “ Thei r pres ent aim s eems to be to obtain specimens that are us efu l as m odels t o Art Industry for which they c ons ider that what I ma y ca ll documentary sp ecimens are not so important.” A. W. Franks, The Ap ology of m y Li fe, about 1893, quoted in A.W.Franks, Nineteenth Century Collecting and the British Museum , Edited by Marjori e Caygi ll and John Cherry, London, 1997. 32. “Gossip in the S outh Kensington Museum ”, Builder, 19th Septemb er, 1868, p. 685, quoted in Anthon y Burton, Vision and Accident, The Story of the Victoria and Albert Museum , London, 1999 p.87. 33. Arthur Lane, Th e English Ceramic Collections in the Victoria and Alb ert Museum, The English Ceramic Circl e Transactions, Vol. 4, 1957 -9, p.20. Borrowing from Collectors: The role of the Loan in the Formation of the Victoria and Albert Museum and its Collection (1852 – 1932) The Decorative Arts Society, P O Box 844, Lewes East Sussex BN7 3NG