Political institutions and the natural resource curse

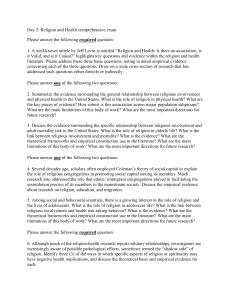

advertisement