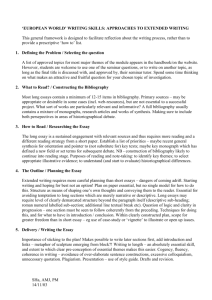

Essay Guidelines - University of Warwick

advertisement

FILM AND TELEVISION STUDIES GUIDELINES FOR WRITING ESSAYS For Introduction to Film Studies 2009/10 Essay writing is a personal and creative activity but it is done within conventions of scholarly practice. Getting a practical sense not just of the balance, but of the relationship between these two aspects will be a large part of your progress. 1. The Purpose of Essays Preparing and writing essays is one of the main ways in which students on the degrees in the Department of Film and Television Studies develop their abilities. It is also through essays, along with invigilated examinations, that the department tests students. An essay is an opportunity to formulate ideas, to set out an argument and to support it with evidence. The argument is yours but it is not just your opinion. Your work should be original, not necessarily in the sense of presenting something never previously thought of, but in taking responsibility for your own argument. Essays sharpen analytic, rhetorical and writing skills that can then be applied to other tasks. These ‘transferable skills’ are highly prized by potential employers who value good communication. 2. Use of Background Material In preparing your essay you will generally consult some historical, critical and theoretical studies relevant to the topic. This background reading may in some cases be less important than your close study of films and televisual works, but it is essential to enable you to extend and focus your own responses. The department encourages the development of individual analytical skills, backed by knowledge and established sources. Essay writing will allow you to explore your own point of view, supported by the evidence you have gathered. With this in mind, make sure you note the details of secondary sources as you read them (see (d) ‘Acknowledgement of sources’ below). Use the notes you have made, but avoid confusing them with a formulation of your own view. The books and articles you consult acknowledge their sources; this is normal academic practice and you must follow it. Note on Plagiarism Plagiarism is the abuse of secondary reading in essays. It consists first of the direct transcription, without acknowledgement, of passages, sentences or even phrases from someone else’s writing, whether published or not. It also refers to the presentation as your own of material from a printed or other source with only a few changes in wording. There is a grey area where making use of secondary material comes close to copying it, but the problem can usually be avoided by acknowledging that a certain writer holds similar views. All quotations from secondary sources, including the Internet, must therefore be acknowledged each time they occur. It is not enough to include the work from which they are taken in the bibliography at the end of the essay, and such inclusion will not be accepted as a defence should plagiarism be alleged. The university regards plagiarism as an extremely serious offence. A tutor who finds plagiarism in an essay will report the matter to the Chair of the Department. The Chair may, after hearing the case, impose a penalty of a zero mark for the essay in question. This can have serious consequences for first-year results. In the case of second-year and third-year students, the matter may go to a Senate disciplinary committee. If plagiarism is detected in one essay, it is likely that other essays by the student concerned will be examined for evidence of the same offence. In practice, few students are deliberately dishonest and cases of plagiarism may arise from bad scholarly practice. There is nothing wrong with using other people’s ideas. In fact one good kind of undergraduate essay is an intelligent survey and synthesis of existing views. The important thing is to know what is yours and what is not and to communicate this clearly to the reader. However, plagiarism is cheating and our academic staff have become extremely efficient at detecting it. 3. Scholarly Presentation Observing certain principles of scholarly presentation for assessed essays is a basic and transferable skill. It aids clarity of communication and enables you to provide a full account of the argument you are putting forward. (a) General presentation Students must submit their essays in word-processed form. A word count must be provided at the end of the essay, and recorded on the front sheet. Footnoted references, along with bibliographies and filmographies, should not be included in the word count, but all other text (including quotations) must be. Use A4 size paper. Print on one side only of each sheet. Number all pages. Unless otherwise instructed, insert your student ID at the head of your essay, on the right-hand side, and on the left-hand side the name of the tutor. Below this should appear the title or question for discussion. Leave wide margins for tutors’ comments on either side of the page, with space also at the top and bottom. Text must be double-spaced. Provide two copies of all essays and dissertations. All essays must include both a bibliography and a filmography. (b) Presentation of titles (films, books etc) and foreign words Titles of films, books, long poems first published individually, television programmes, plays, paintings and periodicals must be italicised. Examples: Citizen Kane; Film Art: An Introduction; Paradise Lost; Big Brother; The Merchant of Venice; The Birth of Venus; Sight and Sound. The titles of articles published in periodicals, essays in edited collections, and short poems in anthologies should be presented in single quotation marks. Example: Laura Mulvey argues in her essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ that… Words or brief phrases in foreign languages, unless they are part of a larger quotation, should also be italicised. Example: A common feature of fin de siècle novels was… (c) Quotations All quotations, from whatever source, should be exact in wording, spelling and punctuation. Short quotations embedded in the main text should be enclosed in single quotation marks and should be accommodated to the syntax of the sentence in which they occur. Three dots (ellipsis) are used to indicate where words or phrases have been cut from a quotation. Accommodation to syntax of sentence is indicated by the use of square brackets ([ ]). Example: In Hollywood Genres, Thomas Schatz claims that ‘the gangster genre has had a peculiar history ... [and that] its evolution was severely disrupted by external social forces’. Quotations within quotations should be differentiated by putting double quotation marks within single ones. Example: According to Schatz, ‘in the words of Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson) in Key Largo: “There are thousands of guys with guns -- but there’s only one Rocco”’. Long prose quotations (i.e. those which take up more than three lines of text) and quotations in verse should be indented by one tab stop from the left hand margin, single spaced – though separated from the surrounding text by an extra line space before and after – and presented without quotation marks. Example: In Jarman’s Edward II, as Edward embraces Gaveston, Annie Lennox sings Cole Porter’s lyrics: Every time we say good-bye I die a little, Every time we say good-bye I wonder why a little. The significance of this anachronistic choice of song is… (d) Acknowledgement of sources Every time you insert a quotation, refer to information, or paraphrase an idea drawn from another writer, you must provide a reference which clearly indicates the original source. There are several referencing systems in operation. Below are guidelines on using the ‘author-title’ system which is the set of conventions most widely used by other departments in the Faculty of Arts and humanities disciplines generally, and which we strongly recommend. For a more exhaustive account of the rules of use for this system please consult the MHRA Style Guide (London: Modern Humanities Research Association, 2002), available in the library. In the author-title system, references are presented as footnotes or endnotes. A numeral in the main text will direct the reader to the equivalent footnote or endnote containing the reference details. All modern word-processing applications have the facility to insert and auto-format footnotes/endnotes. (N.B. The numerals in the main text should ideally be placed at the end of a sentence rather than in the middle of one – even if this means they do not immediately follow the close of a quotation.) On the first occasion that a particular source is referred to, the reference must include full bibliographic details for the source along with the relevant page number. The full references for published sources should always be presented in the format shown below. Examples: 1 Robert Sklar, Movie-Made America: A Cultural History of American Movies (New York: Random House, 1975), p. 56. 2 Richard Maltby, ‘“Grief in the Limelight”: Al Capone, Howard Hughes, the Hays Office, and the Politics of the Unstable Text’, in James Combs (ed.), Movies and Politics (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1992), pp. 104-105. 3 Barbara Klinger, ‘Digressions at the Cinema: Reception and Mass Culture’, Cinema Journal, 28:4 (Summer 1989), pp. 3, 5. N.B. Observe that whilst the references for single-author monographs and edited collections must indicate the place of publication and the name of the publishers of the book concerned, references to periodicals do not. ‘28:4’ in the reference to Cinema Journal means volume 28, issue 4; periodicals which are published less than four times a year tend to count issues by number only. Also note that if a single page is referenced, the abbreviation for the page number is ‘p.’; a reference to more than one page is indicated by ‘pp.’. If you make successive references to the same source, then the Latin abbreviation ‘Ibid.’ (short for ibidem, which means ‘in the same place’) is used in place of the author’s name and the title of the source etc. ‘Ibid.’ is all that is needed if you are referring to the same page from this source in successive references. If you are referring to a different page this must be indicated. Example: 1 Robert Sklar, Movie-Made America: A Cultural History of American Movies (New York: Random House, 1975), p. 56. 2 Ibid. 3 Ibid., p. 58. When further references to the same source do not immediately follow the initial citation, ‘ibid.’ cannot be used. But all subsequent references are shortened to the author’s surname and a succinct version of the source title. Example: 3 Barbara Klinger, ‘Digressions at the Cinema: Reception and Mass Culture’, Cinema Journal 28:4 (Summer 1989), pp. 3, 5. 4 David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (London: Routledge, 1985), p. 23. 5 Klinger, ‘Digressions at the Cinema’, p. 11. 6 Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, Classical Hollywood Cinema, p. 23. When you quote something from a source you have not directly consulted, but which is cited in another secondary source, this must be clearly indicated in your reference. Example: Laura Mulvey has written that ‘Hollywood films made with a female audience in mind tell a story of contradiction, not of reconciliation’.7 7 Laura Mulvey, ‘Notes on Sirk and Melodrama’, Movie 25 (Winter 1977-78), p. 56; quoted in Richard Maltby, Hollywood Cinema (2nd edn.; Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), p. 353. Bibliography All assessed essays must include a bibliography at the end which lists every written source which you have directly consulted. Each entry must include the same amount of publication information provided in the initial reference to the source in your footnotes/endnotes. The only differences in the way this information should be formatted in your bibliography are: Author surnames are listed first (the bibliography must be ordered alphabetically by surnames). If the source consulted was authored anonymously then ‘Anon.’ or ‘ANONYMOUS’ should be written in place of a surname. Page numbers are not needed for listing monographs, but bibliographic entries for essays in edited collections and articles in periodicals should indicate the page range occupied by the essay/article. When an essay from an edited collection is listed, the book itself should be listed separately under the surname of its editor(s) – see the Geraghty / Brunsdon example below. Example: Bibliography: Banton, Michael, The Idea of Race (London: Tavistock, 1977). Brunsdon, Charlotte (ed.), Films for Women (London: British Film Institute, 1986). Fischer, Lucy (ed.), Imitation of Life: Douglas Sirk, Director (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991). Geraghty, Christine, ‘Three women’s films’ in Brunsdon (ed.), Films For Women, pp. 138-145. Malbert, Roger, and Coates, John, Exotic Europeans (London: South Bank Centre, 1991). Newman, Kim, review of Sin City, in Sight and Sound 15:6 (June 2005), pp. 72-74. Vincendeau, Ginette, ‘Gérard Depardieu: The Axiom of Contemporary French Cinema’, Screen 34:4 (Winter 1993), pp. 343-361. Internet citations References must be given for all written material consulted and cited, including internet sources. The conventions for quotations from books and journals (see above) also apply to internet sources, and all such sources should be included in your bibliography. The agreed conventions for internet citations take the following basic form: Author of page/s, name/title of page/s (in inverted commas), name of website (italicised), date of posting (in parentheses; write ‘n.d.’ if this information cannot be ascertained), page number (if indicated)*, URL, date accessed. Example: Ghosh, Arup Ratan, ‘Satyajit Ray’s Male Gaze’, Views, Reviews, Interviews, (2000) <http://www.geocities.com/arghosh/malegaze.html>, accessed 18 May 2003. Online journals often indicate an issue number, just like a published periodical, rather than a specific posting date, and, in such cases, the way in which publication information is presented at source should be duplicated. Example: Norton, Glen W., ‘Nostalgia for the Present: The Godard Renaissance Continued’, Senses of Cinema 35 (April-June 2005) <http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/05/35/godard_renaissance.html>, accessed 12 June 2005. *An increasing number of hard-copy journals are published simultaneously in an online format, and the latter generally replicate the exact layout of the printed version to the extent that they indicate page breaks and page numbers or duplicate the hard-copy in PDF form. Citations of unpublished/non-written sources Lectures There may be occasions when you wish to make clear that certain statistics or ideas which you are presenting in an essay have been taken from a course lecture. The convention for indicating this in a footnote/endnote reference is demonstrated below. Example: 9 Charlotte Brunsdon, lecture given at the University of Warwick, Coventry, 21 January 2007. N.B. Such sources should not be indicated in your bibliography. Films When a film is first mentioned within the text, details of director and/or production company and/or country of origin and the year, should be included. Example: The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, Warner Brothers, USA, 1944). On the first occasion that you refer to a particular character in a film, you should indicate the identity of the actor playing him/her. Example: The main protagonist Philip Marlowe (Elliot Gould) is first seen… All essays must include a filmography, following the bibliography, which should provide details of all films viewed in the preparation of the essay and referred to in the text. A film entry in a filmography usually begins with the title (italicised), and includes the director, the country of origin, and the year. You may include other details that seem pertinent, such as the names of the principal performers or the production company. It is recommended that you include the names of the major characters in brackets after the names of the performers. Example: To Have and Have Not. Dir. Howard Hawks, Prod. Warner Brothers, USA, 1944. Main cast: Humphrey Bogart (Harry Morgan), Lauren Bacall (Slim), Walter Brennan (Eddie). References to films in both notes and main text should include full title with initial capitalisation according to the accepted style of the language concerned. (For courses like National Cinemas I & II where foreign language films are extensively studied, the module leader will explain how titles should be capitalised in the relevant language.) Titles should always be italicised. In the case of non-English language films, original release titles in the original language should be followed by the US and/or British release title. Example: L’Amour violé/Rape of Love. Television or radio programmes When television or radio programmes are discussed or alluded to in your essay, they must also be listed in your filmography. Information for such sources usually appears in the following order: a) b) c) d) e) Title of episode or segment, if appropriate (in quotation marks) Title of programme (italicised) Country of origin Name of channel or network Transmission date. This is abbreviated to ‘tx’, and can be found for all programmes broadcast in the UK after 1995 in the online Television and Radio Index for Learning and Teaching (TRILT) at: http://www.trilt.ac.uk/index.php. Example: ‘Sold’, episode one, Band of Gold, first series, UK, Granada, tx. 12.3.1995. Writer: Kay Mellor, Dir: Richard Standeven, Prod: Tony Dennis Main cast: Cathy Tyson (Carol), Geraldine James (Rose), Barbara Dickson (Anita), Ruth Gemmell (Gina). Within the main text, the first (and only the first) reference made to a television programme should be dated from the year of first transmission and, in the case of long-running serials, the duration of the run should be indicated. Details of production company, channel, country, may be supplied where they are relevant to the argument but otherwise are best left for inclusion in the filmography. Example: Coronation Street (Granada, 1961 -) is notable for its emphasis on strong, witty and independent-minded women. Where writers or producers are credited their role should be indicated. Example: Where the Difference Begins (Writ. David Mercer, BBC, 1961) was one of Mercer’s most important contributions to television drama. DVDs The conventions for referencing information or quotations taken from the audio commentary on a LaserDisc or DVD take the following basic form: Name of speaker, name and date of origin of film, media format, publisher of disc, place and year of disc publication, ASIN code (usually listed on retail websites like Amazon if not on the disc packaging). Example: 4 Kenneth Bowser, audio commentary on Sullivan’s Travels (1941) (DVD, Criterion Collection, USA, 2001) ASIN: B00005JH9C. Marks deducted for poor scholarly presentation Your mark and comment sheet will indicate if you have lost marks for poor scholarly presentation. The conventions which markers use for this are included as Appendix 6 to this handbook. (e) Problems with English There is a close relationship between quality of thought and excellence of expression. One of your goals should be to develop the clarity, vividness and elegance with which you use language as you increase the breadth of your knowledge and the depth of your understanding. A first aim must be to ensure correct usage in spelling, punctuation and vocabulary. Distinguished work presents interesting observations and arguments in a precise and pleasing style, but poor English will affect the level of success you achieve on the degree and will be detrimental to most job prospects. If your spelling is shaky, begin with the list of ‘commonly misspelt words’ at the end of this section. In addition, special care should be taken with the spelling of titles, characters and authors of works being discussed. Do not rely on the ‘spell-check’ facility on your computer. These programs identify non-existent spellings but will fail to respond to typographical errors if the mistake results in an existing word – for example if you type ‘way’ for ‘was’. Students are expected to proof-read essays to eliminate such errors. Whether or not your spelling is weak, use a dictionary regularly. An etymological dictionary and/or a thesaurus can sharpen your style. Certain words are misused with particular frequency. Before using the following, please check their meaning and their grammatical usage: ‘disinterested’, ‘due to’, ‘refute’, ‘imbue’, ‘infer’, ‘quote’ ‘elide’. Check also that you understand the difference between it’s (a contraction of ‘it is’ which you should avoid using in an academic essay) and its to indicate possession (as in ‘the production has its problems’); under the section ‘commonly misspelt words’ you will find other pairs of words often confused with each other. (i) Tutors will indicate where you have made errors of grammar, punctuation and spelling. You are expected to find out why these are errors and not to repeat them. If unsure, consult a grammar. Common faults in grammar include writing sentences with no main verb in them (if you don’t understand what this means, consult a grammar straight away), incorrect use of the colon and semi-colon and misuse of the apostrophe. (ii) Also bear in mind the fact that logically structured argumentation cannot be properly achieved without dividing the different stages of your analysis into separate paragraphs. If you end up writing long passages of text which continue without any pause over several pages then you will fail to communicate your ideas effectively and convincingly. Further reading Some of the information in this handbook is based on Joseph Gibaldi, MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1984), the MHRA Style Guide (London: Modern Humanities Research Association, 2002), and R.M. Ritter, The Oxford Guide to Style (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). We strongly recommend that you consult these sources if you have any further queries. Vocabularies in film and television Film and Television studies draw on many disciplines. Some of the language in your required reading may initially be daunting. If you come across concepts you do not understand, the following dictionaries are recommended: Bottomore, Tom, Harris, Laurence, Kiernan, V.G., and Miliband, Ralph, A Dictionary of Marxist Thought (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1983). Bullock, Allan, Stallybrass, Oliver, and Trombley, Stephen, The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (2nd edn.; London: Fontana Press, 1988) Hayward, Susan, Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (2nd edn.; London: Routledge, 2000). Kuhn, Annette with Radstone, Susannah, The Women’s Companion to International Film (London: Virago, 1990). Stam, Robert, Burgoyne, Robert, and Flitterman-Lewis, Sandy (eds), New Vocabularies in Film Semiotics: Structuralism, Post-Structuralism and Beyond (London: Routledge, 1992). Williams, Raymond, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Fontana Press, 1976). The glossaries in the following books are also useful: Bordwell, David, and Thompson, Kristin, Film Art: An Introduction (7th edn.; London: McGraw Hill, 2003). Kawin, Bruce F., How Movies Work (Berkeley, Oxford: University of California Press, 1992). Maltby, Richard, Hollywood Cinema (2nd edn.; Oxford: Blackwell, 2003). COMMONLY MISSPELT WORDS accommodate accumulate *discreet *discrete pursue portrayal achieve affective (effective) aggravate allusion (illusion) *ante*antiapparent appropriate argument aural (oral) biased blatant *climactic *climatic committee commitment *complement *compliment conscious council counsel criterion (criteria pl.) crucifixion deceive definite degradation *dependant *dependent desperate detached development dilemma divine *dual *duel embarrass emerge (immerse) empirical existence extravagance fulfilment goddess harass heroes hierarchy humorous hypocrisy incite (insight) imminent independent ideology infinite irrelevant irresistible led (lead) lightning (lightening) loneliness lose (loose) loth (loathe) medium (media pl.) metre (pentameter) necessary occasion occurrence parallel perceive personification *practice *practise precede proceed *principal *principle privilege professional *prophecy *prophesy recurrence reminiscent repellent repetition repress rhythm stratum (strata pl.) suppress separate simile subtly subtlety succumb supersede symbolic tendency transience truly *make sure you understand the difference between pairs of words marked by an asterisk