Bristol Cathedral - St George Edgbaston

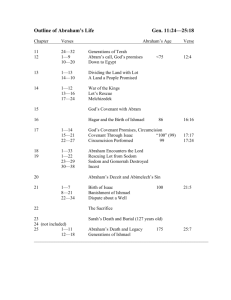

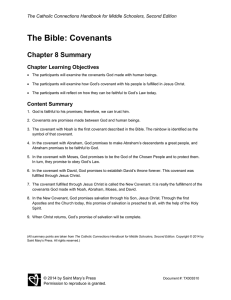

advertisement

A sermon preached by the Very Reverend Robert Grimley St George Edgbaston 1st March 2015 Second Sunday of Lent Today is St David’s day, the anniversary of his death in the sixth century. I mention that because the Welsh population of Birmingham was an important part of its growth during the Industrial Revolution – and when Joan and I moved to Birmingham over 40 years ago, there were still three Welsh-language chapels in the city, so we should acknowledge their patron saint. But St David can also help us reflect on our readings, which are about faithfulness to God, because his last words to his followers were, “Be joyful, and keep your faith and your creed. Do the little things that you have seen me do.” So let’s bear those words of his in mind as we look again at our readings. Let’s start with the reading from Genesis, which tells of the original Covenant between God and his people1. In the non-church context you have perhaps most recently heard the word “covenant” in connection with the Military Covenant – the nation must look after its military, because the military put themselves in danger to protect the nation. More generally, a covenant is a pact, a treaty or a relationship. In the bible the covenant between God and his people has aspects of all of those, so in the passage we heard from Genesis the deal put to Abram is this – “Walk before me and be blameless, and I will make my covenant between me and you, and will make you exceedingly numerous” – in other words, “You live my way, and I will give you unimaginable posterity.” This reciprocity, this two-way obligation between God on one side and his people on the other, is a key feature of Old Testament passages about the covenant. But the idea of a pact or deal alone is not enough to do justice to the 1 idea of covenant which dominates the Old Testament, in addition you need something much more personal, the sort of bond that makes human relationships work properly. One of the most creative and imaginative of the present generation of Old Testament scholars2 was bold enough to go to childcare books to see what there was to be learned about relationships from experts in that field. And he did that because the parent-child relationship, like the Godhumanity relationship is one of unequals, but yet it is the sort of relationship that can mark a whole life, for better of for worse. A key thing about motherchild relationships is that on both sides there has to be a balance between assertion and yielding. Just think about it for a moment: if the mother is always preoccupied with other things, and does not talk and play with the child, the child does not get enough stimulus, and the personality does not develop properly. On the other hand, if the mother is attentive to the child in the wrong way, and gives in all the time, and does not assert any needs of her own, then the child grows up incapable of the normal give and take in relationships with others. Give and take means knowing when it is appropriate to make demands on the other person, and when it is appropriate to yield to the other. As this same expert put it, in a rather clever phrase of his own, good mothering leads to othering, [repeat] and by his made-up word othering, he means learning to be an autonomous person to be a fully-developed “other”, rather than unhealthily dependent on, or subordinate to, someone-else, and he also means learning to relate well to others, in a way that respects their autonomy. Now you might think that this modern child-psychology is a long way from the world of the Bible, but in fact the point is that this crucial balance between asserting oneself over against God, and yielding to him is an essential part of the dynamic of our faith! Let’s very briefly try to see whether this idea 1 2 Genesis 7.1-7, 15-16 Walter Brueggemann, The Covenanted Self. 2 about how we relate to others and to God casts any fresh light on our three readings. First, let’s come back to our Old Testament reading. Did you notice that Abram got a name-change in the bit of the story we read? The traditional explanation is that Abram comes from two Hebrew words Ab-Ram, which mean Exalted Father, or Great Ancestor. The new name Abraham breaks down to Ab-Raham, which means Father of a Multitude. Clearly, the original writer saw the new, God-given, name as representing the promise that Abraham would become the ancestor of a great nation. But what if we look at these two names through the eyes of this othering theory that I have been talking about. AbRam, Exalted Father, could be taken as putting the emphasis too much on an aloof style of leadership. In contrast, Ab-Raham, Father of a Multitude, the God-given name, could prompt us to think in terms of a sense of responsibility for all the people who are caught up in a situation, and not only a responsibility to them, but also a responsibility for them in the sight of God. The implications of that could give us all pause for thought as the political debate hots up with the impending general election! In our second lesson, from Romans3, St Paul picks up the theme of God’s covenant with Abraham, but he uses the term promise; he contrasts two ways of understanding our relationship with God – obedience to the law and trust in God’s unmerited and incredibly generous gift of salvation, what we usually call grace. Now this contrast is much more complicated than it appears here, and Paul, who had all the zeal of the convert from a religion of the Law, was not in the business of providing a carefully balanced view, but just take it on his terms for a moment – do we try to earn salvation, or can we surrender gratefully to God and accept his free gift? In the othering or mother-child way of thinking you could see the mentality of trying to earn salvation as being the wrong sort of autonomy – too prickly, defining oneself over-against God – I’ll do it my 3 way, by my own efforts. Whereas being humble enough to admit dependence on the freely given help and forgiveness of God, is to yield to him in a good and healthy way – think of Isaac Watts’s paraphrase of some more great words of St Paul on this theme, from the Epistle to the Galatians4 Forbid it Lord that I should boast, Save in the death of Christ my God: All the vain things that charm me most, I sacrifice them to his blood. And how does the othering idea work with today’s Gospel reading5? “Get thee behind me, Satan!” That was Jesus’s stinging rebuke when Peter wanted to lay claim to the wrong sort of bond with Jesus – Peter wanted to call the shots, to make Jesus fit into a world in which he, Peter, was putting himself at the centre. And that meant that he was not respecting God’s otherness – God’s need to express his love in his way, which was to be the way of the Cross. Peter wasn’t prepared to wrestle with the idea of a suffering Messiah – he wanted victory and glory as the plain man understands it, and he tried to bounce Jesus into his worldly way of thinking, instead of responding to Jesus’s lead. Jesus knew that God’s way was to be strength through weakness; new life through death, not shying away from death. And although the word Covenant does not occur in the Gospel reading, it is, of course, the death and resurrection of Jesus which brings into being the New Covenant in Christ’s blood, which we celebrate in this and every eucharist. Let’s close with a famous prayer which John Wesley wrote about our relationship with God, and which he encouraged his followers to use every year in what he called a Covenant Service. You will see how in it he balances our autonomy with our need freely to choose to live our lives God’s way, if our relationship with him is to fulfill his purposes. He wrote: 3 Rom 4.13-25 When I survey: Gal 6.14, cf also Eph 2.9 5 Mark 8.31-38. 4 4 I am no longer my own but yours. Put me to what you will, rank me with whom you will; put me to doing, put me to suffering; let me be employed for you or laid aside for you, exalted for you or brought low for you; let me be full, let me be empty, let me have all things, let me have nothing; I freely and wholeheartedly yield all things to your pleasure and disposal. And now, glorious and blessed God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, you are mine and I am yours. So be it. And the covenant made on earth, let it be ratified in heaven. Amen. 5