Contemporary Drug Problems 39(2):311-343, 2012

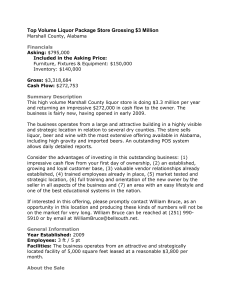

advertisement

Contemporary Drug Problems 39(2):311-343, 2012 Individualised control of drinkers: back to the future? Robin Room AER Centre for Alcohol Policy Research, Turning Point Alcohol & Drug Centre; School of Population Health, University of Melbourne; Centre for Social Research on Alcohol and Drugs, Stockholm University Abstract In recent years, there has been increasing resort in Anglophone countries to individualized control of drinkers. Thus the Australian Northern Territory government has implemented legislation for electronically verifiable identification which must be checked against a banning list of adults prohibited from purchasing alcohol. For another example, alcohol purchase banning orders were instituted in England and Wales by the Blair government. The paper considers the earlier history of such individualized drinking controls, particularly in the alcohol control regimes of the 1920s-1960s which succeeded prohibition regimes or were set up in response to prohibition movements. Questions addressed include what were the rationales of such individualised controls, how were they enforced, why were they largely abandoned, and what evidence is available on their effects. The present-day resurgence of individualised controls is interpreted as the path of least resistance for politicians needing to be seen to do something about alcohol problems without substantially impinging on the alcohol market. Introduction This paper considers a specific strategy for controlling or preventing alcohol problems which has received very little research attention: bans on drinking applied to specific individuals. As we shall discuss, the individual can be banned from purchasing alcohol or drinking at all, or from purchasing or drinking in specific places. The ban can be imposed by a court, by police, or by a single alcohol seller or a group of sellers. To formally ban an individual from drinking or purchasing alcohol is by no means a new strategy, as the paper will discuss, and it has been applied in diverse places. In the U.S. today, for instance, it is very common for judges to impose a requirement of abstinence from alcohol as a condition for parole or probation where the offense is seen as related to drinking.1 Here, however, we will focus initially on two societies, Australia and Britain (particularly England), in which individualised control of drinkers has come to the fore as 1 an alcohol control policy. The paper first documents and discusses these developments in the individualised control of drinkers in both countries. The paper then shows that there is a prehistory of such measures – that individualised control of drinking was a major feature of restrictive alcohol control regimes in the 1920s-1960s -- and considers what evidence there is on their effectiveness in holding down rates of alcohol problems. The paper closes by discussing the ethical considerations which prevailed when such controls were swept away in the 1960s and 1970s, and considers their relevance for alcohol policy today. The present-day drift towards individualised control of drinkers Both in the United Kingdom and in Australia, a long process of expansion of the availability of alcoholic beverages got under way in the decades after the Second World War, resulting in the 1980s and 1990s in a growth of a “nighttime economy” centred on late-night drinking by young adults (Hobbs et al., 2000). In both countries, deregulation of the alcohol market played a major role in the expansion of availability, although other factors such as increased affluence and cultural changes also played a part. As the nighttime economy grew, so did social concerns about the street trouble and violence associated with youthful “binge drinkers”. Youthful intoxication at resorts and festivals in daytime also raised concerns. In both the UK and Australia, there have been a variety of official initiatives to respond to and minimize the trouble. Hadfield et al. (2010), for instance, list twelve new legislative powers and sanctions under six separate pieces of Westminster legislation regulating the nighttime economy that were passed between 1998 and 2006. In both countries, the emphasis has been directed away from alcohol itself and the general conditions of its availability. Neoliberal free-market economics (in such forms as the National Competition Policy in Australia, and European Union single-market regulations in the UK) discouraged attention to the availability of alcohol, as did the strong influence of alcohol beverage industry interests in the political systems (Room, 2006). Some attention was paid in both countries to influencing the conditions of sale and service, but with an emphasis not on regulation but on persuasive approaches such as seeking cooperation between retail sellers and the local police, as discussed below. New market restrictions that were tried out were generally designed to have the least possible interference with the level of sales – an Australian example is the various “lockout” schemes which closed the pub doors to new entrants at some late hour, but did not actually reduce the hours of alcohol sales (e.g., Freeman et al., 2008). In both countries, the political attention therefore tended to focus in the only other available direction: on the drinker. When Britain’s Prime Minister, Tony Blair, turned his attention to drunken anti-social behaviour causing “offence and misery in too many towns and cities on too many Friday and Saturday nights", his proposed solution focused on summary punishment of individual drinkers who got out of line. "A thug 2 might think twice about kicking your gate, throwing traffic cones around your street, or hurling abuse into the night sky if he thought he might get picked up by the police, taken to a cashpoint and asked to pay an on-the-spot fine of, for example, £100” (Anonymous, 2000). Although it turned out that the British police were not keen at the time on that particular solution, Blair’s speech set the tone for a prominent policy approach to the problem in Britain in the 2000s, one that emphasised the individual responsibility of the drinker and sought summary forms of deterrence or incapacitation outside usual criminal court processes. A parallel development got under way in Australia at about the same time. Increasingly in recent times, the approach has extended to banning access to alcohol for those who are seen as misbehaving under its influence. a. Private banning schemes In both the U.K. and Australia, the main initial response to the trouble in the nighttime economy and at youth festivals in the current era came at the local level, particularly from police forces who found themselves stretched to maintain order through long hours among crowds of intoxicated revellers both in drinking places and on the street. By the late 1980s, in both countries police were meeting with local alcohol licensees and encouraging them to link up in voluntary schemes to take measures to reduce the likelihood of trouble and to notify each other of trouble and “troublemakers” as the trouble occurred (Shepherd, 1994; Lang & Rumbold, 1997). In Australia, the schemes which emerged are generally known as community “Liquor Accords”, in the UK as “PubWatch” groups. These schemes usually involve regular meetings of local licensees along with police representatives, and have some means of communicating between bars when trouble breaks out. Among the measures to reduce the likelihood of trouble have often been provisions to ban entry to bars for a period of time for particular drinkers found to have caused trouble. These bans often apply for all drinking places which are part of the local scheme. The ban is imposed by a committee of the local Accord or Pubwatch, and is usually imposed without any court adjudication. As a local British paper explained in a story on the formation of a new local Pubwatch, “bans can be issued for a variety of reasons, including using threatening behaviour towards staff, fighting or drugs offences, and will be imposed by the Pubwatch committee. Pictures of people who are banned are circulated among the pubs to allow staff to recognise offenders” (Anonymous, 2010b). Though UK schemes are characterised as voluntary private associations of businesspersons, they have received much official encouragement. The photographs of banned persons supplied to alcohol licensees are often supplied by the police from their files (Pratten & Bailey, 2005). The UK Metropolitan Police website has a page entitled “Metropolitan Police Pubwatch” which speaks of the “value placed on Pubwatch by 3 both the licensed trade and the police”, gives hints on how to set up a local scheme, and strongly encourages licensees to sign up (Metropolitan Police, 2010). When attendance dwindled at local Pubwatch meetings in a British town in 2001, the local licensing magistrates began to require attendance as a condition of continued licensing (Pratten & Greig, 2005). Given the level of official encouragement and involvement, the legal position that the schemes are private voluntary associations becomes rather fictive. “Police and local authority officers frequently attend Pubwatch meetings and provide administrative support, including delivering banning notices” (Welch, 2010). When bans have been challenged on the grounds of lack of due process, British courts so far have generally ruled that “Pubwatch is not a public body and therefore a review cannot be sought”. But aggrieved drinkers, such as the victim of an assault who was banned along with the aggressor and complained that the banning “decision has ruined his life”, keep trying (Anonymous, 2009). A policeman who is a member of the National Steering Committee of Pubwatch advises police concerning the banning hearings that “Police Officers involved with the supporting of schemes should remember that they are not there to become involved in any decision making process of the scheme and are only there to help, support and advise. By distancing themselves from these processes, they should thereby prevent the scheme from becoming an official or quasi official body open to legal inquiry” (Pratten & Bailey, 2005). The Australian Liquor Accords often have official sanction. In New South Wales, the state liquor licensing authority’s website notes that it “is responsible for promoting the development of effective and sustainable accords across the state. We can help local groups get an accord underway or raise the effectiveness of an existing accord through our Liquor Accord Delivery Unit” (OLGR, 2011). In Victoria, there are 89 local liquor accords with the power under state law to ban people from licensed venues. “Bans are issued by licensees or police without court oversight. The only right of appeal is to a senior police officer” (Munro, 2011b). In October 2011, under pressure of litigation concerning a 21-year-old banned from pubs and bottle shops because of unrelated drug offences, Victorian police lifted the specific ban, although the legislation for liquor accord bans remains in force. b. The ongoing shift to civil-law banning orders In both the UK and Australia, it has become clear to the authorities that the schemes have limited effectiveness as a solution to problems of intoxication in public spaces. Often the most problematic drinking spots do not participate in the Accord; efforts may dwindle when a charismatic police officer who was at the centre of activities moves on; the interests of the licensees often conflict with the interests of public order (e.g., Lang & Rumbold, 1997; Pratten & Bailey, 2005). The limited geographic scope of the schemes may mean that troublesome drinking is exported to the next town (e.g., 4 Watts, 2010). And Pubwatch bans can only be invoked for on-premises misbehaviour – not “if a fight breaks out on the street outside or if … customers are shouted at or threatened on the way home” (Johnson, 2009). For reasons like these, both in the UK and in Australia, there have been moves in recent years to put the control of the drinking of individual drinkers on a regularized legal basis. In Britain, efforts to control individual behavior under the “Respect” agenda of the Blair government, through such means as non-criminal Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (ASBOs), were not at first aimed specifically at drinking behaviour. The Violent Crime Reduction Act of 2006 included the first alcohol-specific control in the form of a “Drinking Banning Order” (DBO), a “civil [court] order which is used to address an individual’s alcohol misuse behavior” by such means as prohibiting entry to places selling alcohol, prohibiting purchase of alcohol, and prohibiting consuming alcohol in public places (CPS, 2010). The ban, which can be applied for by police or local authorities, can apply to specific places, or a specific geographic area, or to the whole of England and Wales, and can be for between two months and two years. Violation of the provisions may bring a fine of up to £2500 and a criminal record. The intention for the DBO was for it to act as a “short, sharp shock”, as opposed to the longer duration of ASBOs (Hadfield & Measham, 2011). The provisions were only put into effect at the end of August, 2009 (Johnson, 2009). The legislation provides that a DBO may also be issued by a criminal court in connection with a criminal conviction, but this provision has only been implemented so far for magistrates’ courts, initially in 25 local justice areas, with a further 25 areas added on 2 November, 2010 (Anonymous, 2010b; Home Office, 2010). By November, 2011, a total of 313 DBOs had been issued (Pescod, 2011). The first ban with nationwide effect was applied in April, 2010 to a 20-year-old woman in Worcestershire who had “been convicted of a series of public order offences, and had flouted bans from pubs and clubs through local Pubwatch schemes” (Dolan, 2010). In recent years, several Australian states have adopted provisions to control individual drinking behaviour, although it is often unclear how much these provisions have actually been applied. New South Wales has a provision for a “self-exclusion agreement” with a particular licensee, where a drinker can fill out an official form with a passport-style photograph and signatures from both the drinker and the licensee agreeing that the drinker will be barred from the premises for 6 months, 12 months or two years (OLGR, 2009). The OLGR site also has a form (AM0343), implementing a 2007 amendment to the licensing laws, which can be filled out by a licensee to seek a banning order barring a named person from the premises for up to 6 months. The form must include “information to satisfy the Authority that the person proposed to be issued with the order has repeatedly been intoxicated, violent, quarrelsome or disorderly on or in the immediate vicinity of licensed premises” (OLGR, 2010). The licensee must be a member of a community Liquor Accord and must pay a fee of $50. No web reference can be found to these provisions having ever been used. 5 A 2007 amendment to the Victorian licensing laws allows police “to prohibit a person from licensed premises or a designated area for 24 hours where they suspect a person has committed an offence, or is acting in an offensive or drunken manner.” By January 2010, police had issued 2144 bans in Melbourne’s central business district in the previous two years (Dowling, 2010b), with a 30% increase in 2009-2010 over the preceding financial year (Munro, 2011a). A separate provision in the law provides that an application can be made to courts for an exclusion order for a particular person from all or specific licensed premises in a designated area for up to 12 months. The person must have been found guilty of alcohol-related violence or disorder within the designated area (Department of Justice, 2008). The designated area must first have been officially proclaimed by the Director of Liquor Licensing. This somewhat unwieldy provision is not often applied: in the year 2009-2010, courts made 32 exclusion orders (Munro, 2010a). In December, 2010, the Nightclub Owners Forum in Melbourne suggested that “all drunks charged with an offence ... should have an endorsement on their drivers licence to this effect for a period of 3 years – for a example an easily recognisable ‘D’ – so that licensed premises are aware of their offending and have the right to reject their entry…”. Peter Iwaniuk, the Forum’s convenor and the owner of four nightclubs (Dowling, 2010a) explained that “our world class entertainment venues were never designed for binge drinkers, but rather responsible adults who are simply out to have a good night. We don’t want patrons who top up (‘preload’) beforehand, or combine alcohol with other drugs. Our late night entertainment industry needs the support of the Government, media and wider community and we deserve to know in advance if someone is a problem drunk” (NOF, 2010). In Western Australia, what was believed to be the first individual prohibition order issued there, banning the person from entering any licensed premise for five years, was issued by the Director of Liquor Licensing in June 2009. A police sergeant was quoted as saying that the police had developed parameters to use the relevant legislation and were pursuing several applications for such bans in response to onepunch or broken-glass attacks (Mason, 2009). On 17 January, 2011 the Western Australia government put into effect new provisions for a “barring notice” which, the police felt, would be a “swifter response” and “more effective than prohibition orders in dealing with less serious offences” (AAP, 2011). Senior police officers (with the rank of Inspector and above) now have the power to ban unruly drinkers from specific pubs and nightclubs, or from particular classes of premises, for up to a year. A banning order of a month or more can be appealed to the state Liquor Commission. “Details [including a photo] of individuals ... with banning orders will be available from a website”. The penalty for breaching a barring notice is a 6 fine of up to $10,000 (DRGL, 2011a; 2011b). An official police site viewed on 10 December, 2011 specified that 15 persons had been barred (WA Police, 2011). In Alice Springs and Katherine, in the Northern Territory, since June 2008 anyone purchasing takeaway alcohol has been required to show an electronic photo identification, so that the licensee can check whether the person is subject to a Prohibition Notice or restrictions on purchase imposed by a court as part of criminal proceedings (NT Department of Justice, 2008). On Groote Eylandt, a large island in the Gulf of Carpinteria with a population of about 2325 (including over 1500 Aboriginal Australians), the formal Alcohol Management System has required since July, 2005 that anyone purchasing alcohol have a permit. In 2006/7, 943 annual permits were issued, including about 45 issued to Aboriginal persons. During the first two years, 39 permits were revoked by a Permit Assessment Committee, mostly for creating a disturbance or fighting or breaching permit conditions. Local informants mentioned that some of the first revocations were of permits for non-Aboriginals. An evaluation showed that incidents in police records dropped substantially after the permit system was instituted; informants reported “reduced fighting and violence in the Indigenous communities, particularly in those communities located closest to the licensed premises”, and that “there was a marked improvement in community harmony and reduction in fighting and other alcohol-related harms” (Conigrave et al., 2007:56). On the Gove Peninsula in Eastern Arnhem Land, a permit system has been in operation since March 2008 in which purchase of takeaway alcohol is limited to persons with permits issued by the police. Permits can be withdrawn or have conditions placed on them by a local Liquor Committee including representatives of social agencies and of the community (NT Licensing Commission, 2006; 2007; personal communication, Peter d’Abbs). In the wake of these local banning and permit schemes, the Northern Territory government has implemented more general legislation. On 1 October, 2010 the first “liquor banning notice” under new legislation was issued by police in Darwin. Such notices can ban a person for up to 48 hours from a designated entertainment district when the person has committed an offence there (Anonymous, 2010a; NT Government, 2010b). In July, 2011 a more ambitious scheme of individualised control went into effect (Starke, 2010; Wood, 2011), including a system of Banning Alcohol and Treatment (BAT) notices or orders which forbid the person to purchase alcohol. A police officer can give a BAT notice lasting up to 12 months to a person placed in police protective custody for intoxication three times in three months; to a person with repeat drink-driving infringements or a serious drink-driving offense; to a person with an alcohol-related offense; or to a person involved in family and domestic violence assaults and offenses involving alcohol. An Alcohol and Other Drugs (AOD) Tribunal set up under the legislation is also be able to issue BAT orders for a year or longer, to require attendance at treatment or rehabilitation, and to review the police notices. Family members and health and welfare workers, as well as police, are able to apply to the Tribunal for a BAT 7 order. The tribunals, headed by an experienced lawyer or magistrate and with one or two other members, are not courts and are not concerned with criminal offenses. Drinkers can also apply for a self-banning order (NT Government, 2010a). Separately from the tribunals, the government also set up a SMART Court (Substance Misuse Assessment and Referral for Treatment), a “drug court” dealing with criminal offenses related to alcohol or drug misuse. Able to operate more flexibly than the existing Alcohol Court, this court also has the power to require persons to attend residential rehabilitation and to ban them from consuming or purchasing alcohol (NT Government, 2010a; Starke, 2010). Those receiving a BAT ban are listed on a Banned Drinker Register. From July, 2011, anyone buying alcohol at any bottle shop in the Northern Territory has had to produce photo identification such as a driver’s licence, and the seller has to check they are not on the Register (Murdoch, 2010). At its start, 500 persons were placed on the list; by 3½ months later, over 1000 more had been added (Kalacouras, 2011; Anonymous, 2011). By early December, 2011, the number was over 1900 (Liston, 2011). c. Where are we now? Both in Australia and the UK, there is clearly a drift towards individualised bans on drinking or purchasing alcohol or being in a drinking place. The ban is triggered by trouble of some kind, though whose drinking caused what trouble will often be a matter of dispute (e.g., Anonymous, 2009; Welch, 2010). The moves towards formal administrative processes concerning the bans may result in greater protection of the rights of those subject to the processes, although it is clear a great deal of discretion about when and how the processes will be applied is left in police and other official hands. Some local areas of the Australian Northern Territory have shifted to a positive requirement of a permit to purchase alcohol (Conigrave et al., 2007), a permit which can be withdrawn in case of trouble. British PubWatch schemes have emphasised secrecy in the process and privacy in the bans, with names and photos of those banned to be kept out of sight of customers, for instance. This theme may be connected to the delicate line the PubWatch schemes are walking as supposedly private groups serving quasi-governmental purposes. It is not clear whether this emphasis will survive the transition to bans imposed by executive and judicial procedures -- the Daily Mail splash naming the first person to be given a nationwide ban (Dolan, 2010) certainly suggests not. Bans under the Australian liquor accord processes, on the other hand, have often been quite public. However, the Northern Territory Banned Drinker Register is not a public document, and access to it is controlled to maintain privacy. Other than for the Groote Eylandt permit scheme (Conigrave et al., 2007), there appears to be little or no research literature on the effect of individualised bans on drinking, either in terms of effects on the drinker and his or her family, or in terms of 8 effects on public amenity and order. The website of the Metropolitan Police in the UK proclaims “Does Pubwatch work? YES” (Metropolitan Police, 2010), but offers no evidence and for that matter no specification of what is meant by this. Even if individual bans do in fact lessen trouble in and around pubs in a particular Pubwatch scheme, the question is left open about net effects on a broader scale – were the drinkers and the trouble simply displaced down the road? It is remarkable that a prevention measure has become so widely diffused with so little published evidence concerning its effects or effectiveness. While there are no general statistics on the number of liquor bans actually imposed, in most places the numbers appear to be quite small, particularly for cases moving through the formal civil legal processes. In the initial months of the Northern Territory Banned Drinker Register, the government claimed that alcohol-related assaults had dropped by 15%, and by 20% in Darwin, the largest city (Anonymous, 2011). On the other hand, thefts from bottle-shops by banned drinkers were reported (Crawford, 2011a), and a substantial black market had sprung up (Crawford, 2011b). At some point in these shifts to individualised controls, alcohol industry interests may decide that the effects of the bans on a significant sector of their potential market outweighs the convenience and positive media coverage to be gained from their part in the banning process. The civil liberties and privacy concerns discussed below are also certain to reemerge. In another time: banning, rationing and tracking of individual drinkers By Schrad’s count (2010), alcohol was prohibited in 13 countries at some time during the period from 1914 to 1935. When prohibition was repealed in the U.S., Canada, Finland and Norway, quite stringent alcohol control systems replaced it in many jurisdictions, with governments monopolising all or part of the alcohol market in 15 US states and in the other countries. The stringency of the controls reflected political deference to the continuing strength of prohibitionist sentiment (e.g., Thompson & Genosko, 2009:17). Sweden also had adopted a stringent control system – which was a major reason, in fact, that prohibition was voted down there by 51% in a 1922 referendum (Johansson, 1995). Modern discussions of these control systems usually emphasise their general population controls on consumption – measures such as high taxes and prices, limited numbers of outlets and times of availability. But in their earlier history many of the systems also involved highly-developed systems of individualised control. All Canadian provinces, for instance, had systems of individual permits for purchasing alcohol (although in three provinces only for a short time during the Second World War), as did five U.S. states with state alcohol monopoly systems (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:14). The individualised controls were often more flexible than individual prohibition’s 9 outright ban – the option often existed of limiting the amount of alcohol which an individual could purchase, rather than completely banning sales to them. No specific cross-national account is available of the individualised control aspects of these systems. Given the modern re-emergence of such systems, it seemed useful to give brief descriptions of the arrangements for individualised control in three of these systems, and of what evidence there is of their effectiveness, drawing from the available secondary literature. The prime focus in all the cases discussed is off-sales of alcohol.2 a. Sweden: Bans and limits in a comprehensive individualized rationing system The Swedish system between 1916 and 1955 had the most comprehensive system of individualised controls. In this period, in order to purchase alcoholic beverages it was necessary to be aged 25 or above and to have a “motbok”, which both identified the holder as permitted to buy alcohol and kept track of purchases (including amounts) of all alcoholic beverages (Bruun & Frånberg, 1985:65; Frånberg, 1987). Each holder of a valid motbok had a monthly allowance of spirits, then the primary Swedish alcoholic beverage, of up to a maximum of 4 litres per month (3 litres in some periods). As this system of control developed in the 1920s, it was established that having a motbok ration was a privilege, not a right, to be granted according to a “principle of need” of intoxicating drinks. Factors listed as legitimate considerations in deciding on whether a ration should be granted and of what quantity included: gender, age, whether the person had their own household, lifestyle, economic stability, whether taxes were paid up, indigent circumstances, whether identified as a problematic drinker by the Temperance Board, and which county and city the person lived in (Bruun & Frånberg, 1985:97). As a matter of course, married women were rarely given a motbok. References from two persons were required for those seeking a full ration (p. 98). Parallel to the rationing system, Sweden developed a system of Temperance Boards, quasigovernmental committees in each community, often chaired by the local schoolteacher or pastor, charged with the dual functions of counselling and coercing those whose drinking was seen as problematic by the police or the community (Bruun & Frånberg, 1985:154-189; Rosenqvist & Takala, 1987). It was argued that this arrangement gave the system “a philanthropic and social character”, as opposed to “a repressive character, the character of criminal law, which was something to be avoided” (Rosenqvist & Takala, 1987:26, quoting the instructions to the Boards from 1934). In the early years of the system, Temperance Boards impounded many motboks themselves (2,600 in 1920), but the numbers impounded diminished to 400 by 1929. However, the numbers of motboks impounded by the retail sales system itself because of confidential advice from Temperance Boards rose to 4,200 in a year by 1936. This was a majority of the 6,000 or so motboks withdrawn each year in the 1930s and 1940s 10 – a figure which amounted to about 0.25% of all drinkers in Sweden (Bruun & Frånberg, 1985: 154, 230). The cumulative effects of the control system were quite pervasive. In an accounting at the end of 1945, about 70% of Swedish males aged 25+ were “motbok owners”, that is, had at some time had a motbok. Of all males 25+, 10% had had their motbok refused or withdrawn, and the purchase rights of another 11.4% had been reduced or restricted (Bruun & Frånberg, 1985:230). As might be expected from these figures, there was substantial protest against the system, but a Gallup poll in 1950 showed that the supporters of the system were still almost even (46%) with those against it (48%) (Bruun & Frånberg, 1985: 229-262, 260). In 1955, the motbok system was abolished. The work of the Temperance Boards was transferred to the social welfare authorities in the 1960s. Despite several reconsiderations, Sweden has kept a system of civil-court compulsory treatment for alcohol problems, with about 500 cases committed to treatment by a civil court process each year. The results of the abolition of the motbok in 1955, to be further discussed below, were quickly apparent. Total consumption rose, and indicators of very heavy drinking such as mortality from liver cirrhosis rose even more (Norström, 1987). In an effort to curtail these negative developments, alcohol prices were raised. Also, registers of those banned from purchasing were again set up. “Temperance Boards provided the salespeople [in the government retail stores] with a file of blacklisted persons in the region and the salespeople, in turn, were in charge of refusing these people access to the liquor store” (Tigerstedt, 2000). Rules of banning from purchases and of identification control were tightened in 1963 and 1964. Those who had been sentenced for drunkenness more than once in a year were put on a blacklist for purchases. At first, about 20,000 a year were affected by this; in 1974 the number had dropped to 11,000, and in 1977 the blacklists were eliminated. Starting in 1980, there was discussion for several years of bringing back rationing and registration, with every third Swedish doctor and 200,000 other Swedes signing an appeal for such measures (Tigerstedt, 2000), but with no action taken. b. Finland: buyer surveillance and control The Finnish system of “buyer surveillance”, as it was called in English, did not exist from repeal of Finnish prohibition in 1932, but first arose as a system of purchase permits in wartime, in 1943 (Järvinen, 1991), which was extended to the whole country by 1948 (Mäkelä et al., 2002:20-21). Most purchasers were authorised to purchase at only one outlet, which increased the effectiveness of the controls. At first, days of purchase were stamped on the permit, and later the amounts purchased were also recorded. “In cases of extensive purchases – determined by the customer’s age, sex and income – detailed interrogations were carried out. Inspectors from the stores called on 11 the customer at home; they interviewed neighbours and obtained relevant information on the customer from the police and social authorities.... The purchase card could be suspended for a maximum of a year if he was registered for alcohol problems, drinking offenses or poor relief” (Järvinen, 1991). The buyer surveillance effort was quite a substantial effort, with 215 people employed in it in 1952 (Lanu, 1956:244). In 1955, there were over 15,000 customers whose purchase permits had been revoked (Mäkelä et al., 1981:45), somewhere near 1% of all who drank at all, while many others had their purchases restricted (Järvinen, 1991). Throughout the system’s existence, it covered spirits. In 1949, beer and wine were removed from the permit system, and fortified wine also from 1952 to 1958 (Mäkelä et al., 2002). The corps of inspectors and the buyer surveillance system were discontinued in the mid-1950s (Klaus Mäkelä, personal communication), and the system of general registration of all purchases was abolished in 1957. “In the 1960s records were kept only for persons strongly suspected of addiction” (Järvinen, 1991), and the purchase cards were finally discontinued in 1971 (Mäkelä et al., 1981). c. Ontario: liquor interdictions, prohibitions, preventative cancellations From repeal of Ontario’s prohibition in 1927 until 1962, persons wishing to purchase alcoholic beverages in Ontario were required to have a Liquor Permit, renewed each year. A customer with such a permit would fill out a purchase order at the provincial store; the permit book would be inspected, until 1958 the date of each visit and the nature of each purchase would be recorded in it, and after 1930 also the cumulative cost of the purchases (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:44, 46, 83). From 1927 until 1975, the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) maintained a “drunk list” of persons forbidden to purchase alcohol. The means by which a person was placed on that list varied over the years; there were judges’ Interdiction Orders, from 1929 to 1965 a Prohibited List which included welfare recipients, and from 1930 to 1975 Preventative Cancellations of the liquor permit (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:94-100). Applications for an investigation for a person to be placed on the drunk list came from many sources: most commonly from the police or from the wife or a family member, but also from a variety of provincial officials, including LCBO staff (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:134). The LCBO had an investigative process which might include interviewing the permit holder, the employer, family members, and neighbours. Over 90% of the investigations resulted in some action by the LCBO – 80% in purchasing bans, 9% in warning letters, and 2% in limits on consumption (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:154). If a limit was placed on consumption, a “Regional stamp” would be placed on the book, limiting purchases to a store near the customer’s location, with a notation of what limit had been imposed (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:48-50). Actions taken by the LCBO would be communicated with letters to the customer, to police stations, and 12 to bars and beer and LCBO stores in the customer’s region (Thompson & Genosko, 2009: 13, 105-109). The LCBO made over 4,000 banning orders each year in the late 1940s (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:103). This represents somewhere around 0.25% of the drinking population of Ontario at the time, although many facing a certain ban would probably not have applied for a Liquor Permit. The system was gradually dismantled from 1958 on, when purchase recording was abandoned. The Liquor Permit was abolished in 1962. Purchase orders disappeared with the advent of self-service stores in the 1970s. In 1974, a court decision halted the LCBO interdiction process by holding that there was a “denial of natural justice since the recipient of the order has no right to defend himself at a proper hearing”. The interdiction process was reorganised as a more open hearing by a different provincial agency, but finally abolished in 1990 (Thompson & Genosko, 2009: 189-190). Evidence on effectiveness: very limited Both Ontario and Finland had alcohol research institutions with connections to the government alcohol monopoly in place when the individual control systems were dismantled, and Sweden had a tradition of government investigations which to some extent filled the same function. But evaluations at the time of the effects of the banning systems or of the policy changes were limited to a dissertation (Lanu, 1956) and another study (Sääksi, 1960) in Finland. In an ex-post-facto experiment comparing in 1952 a sample of “alcohol abusers” who had been subject to an intervention in 1949 (questioning, warning, or a temporary purchase ban) with a matched sample of “alcohol abusers” with no such intervention, Lanu (1956) found only small differences in consumption in 1952 (Mäkelä et al., 2002:20-21). He concluded that “it could not be observed” that buyer surveillance has had any favourable effect on the “alcoholic behaviour of misusers”. The study had relatively small samples, which meant that the intervention would have had to have a strong effect to find significant results – stronger than is usual for clinical interventions with heavy drinkers. Nevertheless, the study served as a justification for the abandonment of the buyer surveillance system. On the other hand, a small study in Tampere, an industrial city, in 1954-1955, did find that whether their purchases were recorded in their liquor permit had effects on purchasing, particularly for urban misusers (Sääksi, 1960; Mäkelä et al., 2002:21). Despite these findings, the recording of purchases was abolished in 1957. In Sweden, there was much debate during the motbok period about its effects, with the temperance movement playing a considerable part in arguing against the continuance of the system (Bruun & Frånberg, 1985:318-336).3 As noted, immediately after its demise the system’s effectiveness became apparent: consumption rose by 25% in the first two years, and serious consequences rose more sharply; thus deaths from delirium tremens rose from about 160 per year to over 700 (Bruun & Frånberg, 13 1985:331). Much of the change was due to a change in the distribution of consumption, with heavier drinkers disproportionately increasing their drinking (Norström, 1987). What is not clear, however, is how much the effectiveness of the system can be accounted for by the rationing system, with its upper limit on purchases, and how much by the individualization of controls, in which particular drinkers were banned from or severely limited in their purchases. There is evidence from elsewhere of the effectiveness of rationing systems (Schechter, 1986), and it may be that this side of the system accounted for most or all of the effectiveness. A rationing system limits the ability and willingness of others to purchase on behalf of the banned drinker. As for Ontario, as Thompson and Genosko (2009:194) suggest, “the coincidence of dates of removal of certain of the LCBO’s administrative technologies … and increased consumption suggest the need for further linkage between these two factors”. But there seems to have been no such study. Looking at the work of the International Study of Alcohol Control Experiences (ISACE) in the period 1950-1980, in which the present author took part, it is surprising to note that the LCBO’s individualized controls of the 1950s are not even mentioned. The closest the ISACE chapter on Ontario comes to mentioning the individualized controls is a discussion of the introduction of self-service stores (Single et al., 1981:152-153). Overall, then, it must be said that the alcohol research literature is not strong on studies of the effect of individualized bans on drinking or purchasing alcohol. From the Swedish experience, it is clear that a combination of restrictive measures did have a substantial effect, particularly on drinkers inclined to drink heavily and problematically. But individual bans were probably not the most important contributor in this result. About the effect of individual bans, in isolation from other measures, there is very little evidence. The turn 50 years ago against individualised control measures In each of the three cases considered above, there was a turn, starting in the latter part of the 1950s, against individualized alcohol control systems. This can be seen as part of a broader turn at that time against singling out individuals for social handling: this was an era of movements to decriminalise “status offenses” or what were described as “victimless crimes” – including, for instance, public drunkenness (Room, 1976). In North American sociology at the time, theories of deviance played a leading role in analyses of social problems, emphasising the often detrimental effects of singling out norm-breakers from the population and labelling them as deviant (Becker, 1963; Lemert, 1967). In a parallel fashion, Nordic criminologists were mounting a critical attack on traditions of singling out habitual “alcoholists” and subjecting them to regimes of compulsory labour (Christie, 1960; Hauge, 2007). In the course of the 1960s, there was also heightened attention to discrimination in the application of law on the basis of general social categories such as gender or race. 14 One common feature of the later historical analyses of the cases we have considered is the considerable critical attention often paid to what are seen as the discriminatory features of the systems (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:145-188; Bruun & Frånberg, 1985:298-317; Campbell, 2001:79-105; Järvinen, 1991). The discrimination was often built into the system. Even when it was not, the prejudices of those processing individual cases one by one were almost certain to have discriminatory results. Such features made the systems vulnerable in the new era to human rights-oriented attacks. In the Nordic countries, in particular, these considerations were part of the attraction of the “total consumption model” for alcohol policy as it developed as a paradigm. The model offered an approach to alcohol policy based on projected risk rather than on an already-existing event or condition, and directed not at individuals but at populations (Tigerstedt, 2000). Also, although publications taking the “total consumption” approach flew the flag of public health, many were written by sociologists and other social scientists, influenced by the new themes in sociology and criminology. For instance, social scientists were in a majority among the authors of Alcohol Control Policies in Public Health Perspective (Bruun et al., 1975). So another argument was often made, alongside arguments that population-directed control measures were more effective or cheaper than policies involving individual “social handling”, such as individual warning, treatment or punishment. Also, it was argued, the populationoriented measures were ethically preferable: “the labelling of individuals as a part of such strategies ... carries social costs in that it tends to be applied to those with the least social resources to protect themselves” (Bruun et al., 1975:67). So is it back to the future? Until Tony Blair put forward his proposed solution to drunken yobs (Anonymous, 2000), individualised banning orders on purchasing alcohol seemed to be a feature of a bygone era. I suspect that this is why the LCBO’s individualised control system was missing from the ISACE report: by 1980 it had already disappeared from the armamentarium of alcohol control. As documented in the first part of the paper, the strategy is now back and gaining strength, at least in Australia and the U.K. The pressure to adopt such measures comes from the confluence of two sets of forces. On one side is the rise of alcohol problem rates in both countries, and the sharp rise in public attention to alcohol problems, particularly in terms of the nighttime economy and youth clubbing and festivals. In this circumstance, politicians need to be seen to be doing something. One option would be to take the advice of public health constituencies arguing for “population measures” -- higher taxes and decreased availability. But such measures are strongly opposed by forces pushing on the other side. One of these is the continuing dominance of the ideology of free markets and consumer sovereignty, which has pushed in both countries towards ever-increasing availability, and to a considerable extent is locked in by competition policy in Australia 15 and EU single-market policies in the UK. The other is the very considerable influence of the various parts of the alcohol industry in the politics of both countries. The moves toward individualised control can be seen as an attempt to solve these dilemmas. For alcohol industry interests, individualised control has long been a direction in which to point. Already in 1931, in his textbook on Liquor Control, Catlin (1931:244) noted that “associations representative of the brewing and distilling interests have repeatedly urged that nothing would give them more satisfaction than to see the penalties increased against drunkards whose topings only serve to bring a legitimate trade into disrepute, but that the honest man should be free to have his glass of beer or whisky unhampered....” In the same vein but up to the minute is the statement of the convenor of the Melbourne Nightclub Owners Forum: “In today’s society to only put blame on the alcohol service provider is not working. Despite the best management arrangements, service providers can be tricked by customers with psychological issues, or malicious or criminal intent. The consumer must be made to take responsibility and face the consequences of their actions before any meaningful change in behaviour can be achieved.” (NOF, 2010) But the experience from the past that we have described suggests that difficulties loom ahead down the path of individualized controls. It is doubtful that substantial implementation of such schemes can long evade demands for due process, which are likely to slow down the process and raise costs. If such a scheme is to have any effect at a population level, the costs of implementation are likely to be considerable. And the evidence that such schemes have the intended effects is at this point limited to an isolated environment, Groote Eylandt. If the individualized controls were actually to be effective, it seems most probable that alcohol industry interests would rapidly lose interest in promoting them. A system as effective as Sweden’s motbok system in holding down heavy consumption, for instance, would be damaging to alcohol firms’ economic interests. Then there are the ethical issues which helped to kill the schemes of the 1940s and 1950s. Individualised controls of purchasing or consuming alcohol are likely to be felt by many to be an invasion of privacy. The issues of stigmatisation and marginalisation in connection with individualized social processing will recur. And questions are likely to arise soon after implementation about discrimination in application, whether by race, class or otherwise. Despite its apparent political attractions, the path of individualized controls is likely to prove to be strewn with rocks and landmines. As the experience from 60 years ago illustrates, individualised controls should not in any case be viewed as alternative to population-oriented strategies. Relying solely on individualized control strategies while allowed free rein to promotion and to building the market – to attracting yet more youthful drinkers into heavy drinking in the 16 nighttime economy -- is a combination of strategies that is both ethically questionable and likely to fail. AUTHOR’S NOTE: Revised from a presentation at the 37th annual Alcohol Epidemiology Symposium, Kettil Bruun Society for Social and Epidemiological Research on Alcohol, Melbourne, 11-15 April, 2011. Work on this paper was conducted under a professorship financed by the Victorian Department of Health and the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education, Canberra. Thanks to Klaus Mäkelä for help on Finland, to Peter d’Abbs and Sarah MacLean for help on the Northern Territory, and to Gretchen Thomas for editing. ENDNOTES 1 Such requirements differ from the bans we will discuss here in that, in principle at least, they include individualised monitoring of compliance (e.g., Voas et al., 2011). Individualised control of drinking by civil legal process has a considerably longer history than is covered here. The UK Liquor License Act of 1883 (c. 30, s. 92[1]), for instance, provided that When it shall be made to appear in open court that any person, by excessive drinking of liquor, misspends, wastes, or lessens his estate or greatly injures his or her health, or endangers or interrupts the peace and happiness of his or her family, the justices holding such court shall, by writing under the hands of two such justices, forbid any licensed person to sell him or her any liquor for the space of one year. (quoted in Thompson & Genosko, 2009:91) But actions by judges under such provisions tend to be relatively sparse. The private or administrative actions we discuss here are capable of much wider application. In Ontario, for instance, such legal interdictions by judges in the years before 1952 averaged only 21 per year, compared to an average of over 4,000 administrative bans were imposed each year in the late 1940s by the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) (Thompson & Genosko, 2009:103, 118). 2 In the historical period discussed, off-sales were the primary outlet for alcoholic beverages in Sweden, Finland and Ontario, although each of these systems also had aspects concerned with controls of on-premise drinking in restaurants, which fed into the individualised control system (e.g., Bruun & Frånberg, 1985: 115-153). There are also a few discussions of individualised bans in historical studies of the control of onpremise drinking in other places, though often focusing on institutionalized racial and sexual discrimination (e.g., for British Columbia, Campbell, 2001:79-105). 3 While the temperance movement’s position reflected some particular history in Sweden, it also reflected the general distaste of prohibitionists for the competing 17 ideology of “liquor control”, particularly with the state itself in the business of selling the stuff (Room, 2004). REFERENCES AAP (2011) Unruly drinkers face pub bans. The West Australian, 13 January. http://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/a/-/latest/8643913/unruly-drinkers-face-pubbans/ (accessed 17 Jan., 2011) Anonymous (2000) PM proposes spot fines for hooligans. Guardian (London) 30 June. http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2000/jun/30/uk.politicalnews3 (accessed 29 Dec., 2010) Anonymous (2009) Pubwatch bans face further High Court test, Morning Advertiser, 26 January. http://www.morningadvertiser.co.uk/news.ma/article/81836 (accessed 28 December, 2010). Anonymous (2010a) First liquor banning notice issued – Darwin City. AUSTRALIA.to NEWS website, 1 October. http://www.australia.to/2010/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=44 63:first-liquor-banning-notice-issued--darwin-city&catid=134:news-wire&Itemid=247 (accessed 29 Dec., 2010) Anonymous (2010b) New Pubwatch will bar troublemakers, Buxton Advertiser, 15 June. http://www.buxtonadvertiser.co.uk/news/local/new_pubwatch_will_bar_troublema kers_1_903115 (accessed 28 Dec., 2010). Anonymous (2011) Fights down due to banned register: Govt. NT News, 17 October. http://www.ntnews.com.au/article/2011/10/17/266931_ntnews_pf.html (accessed 17 October, 2011) Becker, H.S. (1963) Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Free Press. Bruun, K., Edwards, G., Lumio, M., Mäkelä, K., Pan, L., Popham, R.E., Room, R., Schmidt, W., Skog, O.-J., Sulkunen, P. & Österberg, E. (1975) Alcohol Control Policies in Public Health Perspective. Helsinki: Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, Vol. 25. Bruun, K. & Frånberg, P., eds. (1985) Den svenska supen: En historia om brännvin, Bratt och byråkrati [The Swedish snaps: A history of booze, Bratt, and bureaucracy]. Stockholm: Prisma. Campbell, R.B. (2001) Sit Down and Drink Your Beer: Regulating Vancouver’s Beer Parlours, 1925-1954. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Catlin, G.E.G. (1931) Liquor Control. Home Universities Library. New York: Henry Holt & Co., and London: Thornton Butterworth. 18 Christie, N. (1960) Tvangsarbeid og alkoholbruk [Forced labour and alcohol use]. Oslo: Universitetsførlaget. Conigrave, K., Proude, E. & d’Abbs, P. (2007) Evaluation of the Groote Eylandt and Bickerton Island Alcohol Management System. Darwin: Northern Territory Department of Justice. http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/healthresources/programs-projects?pid=595 (accessed 11 Jan., 2011) CPS (2010) [Legal Guidance:] Drinking Banning Orders (DBOs) Sections 1-14 Violent Crime Reduction Act 2006. Updated 29 March. London: Crown Prosecution Service. http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/d_to_g/drinking_banning_orders (accessed 27 Dec., 2010) Crawford, S. (2011a) Banned drinkers just turn to theft. NT News, 18 October. http://www.ntnews.com.au/article/2011/10/18/267051_ntnews_pf.html (accessed 19 October, 2001. Crawford, S. (2011b) Police net closing on grog scam. NT News, 16 September. http://www.ntnews.com.au/article/2011/09/16/260601_ntnews_pf.html (accessed 19 October, 2011) Department of Justice (2008) Changes to the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998. Melbourne: Victorian Department of Justice. http://www.justice.vic.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/Safer+Streets/Home/On+the+Stre et/SAFER+STREETS+-+Exclusion+Orders (accessed 28 Dec., 2010) Dolan, A. (2010) Woman becomes first person banned from EVERY pub and club in the country. Daily Mail (London), 16 April. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article1266298/woman-person-banned-every-pub-club-country.html (accessed 28 December, 2010) Dowling, J. (2010a) Nightclubs call for branding of licences. The Age (Melbourne), 22 December. http://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/restaurants-andbars/nightclubs-call-for-branding-of-licences-20101221-194ie.html (accessed 15 Jan., 2011) Dowling, J. (2010b) Police issue record number of banning notices. The Age (Melbourne), 26 January. http://www.theage.com.au/national/police-issue-recordnumber-of-banning-notices-20100125-muhi.html (accessed 28 Dec., 2010) DRGL (2011a) Barring Notices. Perth: Department of Racing, Gaming and Liquor. https://rgl.wa.gov.au/ResourceFiles/Policies/Barring_Notices.pdf (accessed 15 Jan., 2011) DRGL (2011b) Regulating Behaviour on Licensed Premises. Perth: Department of Racing, Gaming and Liquor. https://rgl.wa.gov.au/ResourceFiles/Publications/FactSheetBehaviouronLicensedPre mises.pdf (accessed 15 Jan., 2011) Frånberg, P. (1987). “The Swedish Snaps: A History of Booze, Bratt, and Bureaucracy” -A summary, Contemporary Drug Problems 14:557-611. 19 Freeman, J.E., Palk, G.R. & Dewey, J.D. (2008) Reducing alcohol-related injury and harm: The impact of a licensed-premises lockout policy. Proceedings, 9th World Conference on Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion, Merida, Mexico. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/13235/1/13235.pdf (accessed 15 January, 2011) Hadfield, P., Lister, S. & Traynor, P. (2010) “This town’s a different town tonight”: policing and regulating the night-time economy, Criminology & Criminal Justice 9(4):465-485. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2854627/ (accessed 29 Dec., 2010) Hadfield, P. & Measham, F. (2011) Lost Orders? Law Enforcement and Alcohol in England and Wales. London: The Portman Group. http://www.portmangroup.org.uk/?pid=39&level=2 (accessed 10 December, 2011) Hauge, R. (2007) On the demise of the Norwegian Vagrancy Act. In: Edman, J. & Stenius, K., eds. On the Margins: Nordic Alcohol and Drug Treatment 1885-2007, pp. 169-184. Helsinki: Nordic Council for Alcohol & Drug Research, NAD Publication No. 50. http://nordicwelfare.org/filearchive/8/87093/50publikation.pdf (accessed 17 Jan., 2011) Hobbs, D., Lister, S., Hadfield, P., Winlow, S. & Hall, S. (2000) Receiving shadows: governance and liminality in the night-time economy. British Journal of Sociology 51(4):701-717. Home Office (2010) Guidance on Drinking Banning Orders on Application and Conviction for Local Authorities, Police Forces, Courts and Course Providers within England and Wales. Issued 16 November. London: UK Home Office. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/alcohol/guidance-drinking-banningorder?view=Standard&pubID=836474 (accessed 28 Dec., 2010) Kalacouras, K. (2011) First drunk added to banned list. NT News, July 1. http://www.ntnews.com.au/article/2011/07/01/244421_ntmews_pf.html (accessed 19 October, 2011) Järvinen, M. (1991) The controlled controllers: women, men and alcohol. Contemporary Drug Problems 18(3):389-406. Johansson, L. (1995) Systemet Lagom: Russdrycker, Interesseorganisationer och Politiker Kultur under Forbudsdebattens Tidevarv 1900-1922 [The middle-way system: alcohol, interest organizations, and political culture in the days of the debate about prohibition, 1900-1922]. Lund: Lund University Press. Johnson, A. (2009) Curbing loutish alcohol misuse. Guardian (London), 31 August. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/aug/31/alcohol-drinking-banningorders (accessed 28 December, 2010) Lang, E. & Rumbold, G. (1997) Effectiveness of community-based interventions to reduce violence in and around licensed premises: a comparison of three Australian models. Contemporary Drug Problems 24(4):805-826. 20 Lanu, K.E. (1956) Poikkeavan alkoholiläyttäyty misen kontrolli: Kokeellinen tutkimus muodollisen kontrollin vaikutuksesta alkoholikäyttäytymiseen [Control of drinking behaviour: an experimental study in the effect of formal control over drinking behavior]. Helsinki: Väkhuomakysymyksen tutkimussäätiö. Lemert, E. (1967) Human Deviance, Social Problems and Social Control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Liston, G. (2011) Top cop says banned drinkers register is working. ABC News, 6 December. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-12-06/20111206-mcroberts-backsbanned-drinker-register/3715568 (accessed 10 December, 2011) Mäkelä, K., Österberg, E. & Sulkunen, P. (1981). Drink in Finland: Increasing alcohol availability in a monopoly state. In: Single, E., Morgan, P. & de Lint, J., eds. Alcohol, Society, and the State, 2: The Social History of Control Policy in Seven Countries, pp. 31-60. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation. Mäkelä, P., Rossow, I. & Tryggvesson, K. (2002) Who drinks more and less when policies change? In: Room, R., ed. The Effects of Nordic Alcohol Policies: What Happens to Drinking and Harm When Alcohol Controls Change? pp. 17-70. Helsinki: Nordic Council for Alcohol and Drug Research, NAD Publication No. 42. http://www.nordicwelfare.org/filearchive/8/87237/42publikation.pdf (accessed 15 Jan., 2011) Mason, F. (2009) Pub ban for ‘violent’ drinker. In My Community website, 12 June. http://www.inmycommunity.com.au/news-and-views/local-news/Pub-ban-forviolent-drinker/7527920/ (cached by Google 27 Nov. 2010, accessed 28 Dec., 2010) Metropolitan Police (2010) Metropolitan Police Pubwatch (website). London: Metropolitan Police. http://www.met.police.uk/crimeprevention/pubwatch.htm (accessed 29 Dec. 2010). Munro, P. (2011a) Lawyers challenge police alcohol ban powers. The Age (Melbourne), July 31. http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/lawyers-challenge-police-alcohol-banpowers-20110730-1i5pa.html (accessed 19 October, 2011) Munro, P. (2011b) Police back down over pub bans The Age (Melbourne), 16 October. http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/police-back-down-over-pub-bans-201110151lqhz.html (accessed 19 October, 2011) Murdoch, L. (2010) Tough territory for problem drinkers. Sydney Morning Herald, 1 November. http://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/lifematters/tough-territory-forproblem-drinkers-20101031-178y6.html (accessed 29 Dec., 2010) NOF (2010) Nightclub owners want problem drunks to have drivers licenses marked. Press release, 21 December. Melbourne: Nightclub Owners Forum. http://www.nightclubownersforum.com/id11.html (accessed 17 January, 2011). Norström, T. (1987) The abolition of the Swedish alcohol rationing system: Effects on consumption distribution and cirrhosis mortality. British Journal of Addiction 82(6):633-641. 21 NT Department of Justice (2008) Licensing Regulation and Alcohol Strategy. Factsheets. Darwin: Department of Justice. http://www.nt.gov.au/justice/licenreg/documents/liquor/fs_asp_id_system.pdf; http://www.nt.gov.au/justice/licenreg/documents/liquor/fs_asp_question_answers. pdf (both accessed 11 Jan., 2011) NT Government (2010 a) Banned Drinkers and the.Smart Court. Fact sheet, “Enough is enough’ campaign. Fact sheet. Darwin: Northern Territory Government. http://www.alcoholplannt.com.au/media/pdf/FactSheet_Banned_Drinkers.pdf (accessed 29 Dec., 2010). NT Government (2010b) Licensing, Regulation and Alcohol Strategy: Designated Areas, Banning Notices & Exclusion Orders. Fact sheet. Darwin: Northern Territory Government. http://www.nt.gov.au/justice/licenreg/documents/liquor/ 5_fact_sheet_licensees_designated_areas%20_banning_notices.pdf (accessed 29 Dec., 2010). NT Licensing Commission (2006) Reasons for decision: Application for declaration of a Restricted Area and Permit System. Darwin: NT Licensing Commission. www.nt.gov.au/justice/commission/decisions/061006_Gove_Peninsula.pdf (accessed 11 Jan., 2011) NT Licensing Commission (2007) Reasons for decision: Application by the East Arnhem Harmony Mayawa Mala Inc…. Darwin: NT Licensing Commission. http://www.nt.gov.au/justice/commission/decisions/071217%20Gove%20General% 20and%20Public%20Restricted%20Area%20Decision.pdf (accessed 11 Jan., 2011) OLGR (2009) Self-exclusion agreements. Sydney: New South Wales Office of Liquor, Gaming and Racing. http://www.olgr.nsw/gov,au/liquor_self_exclusion_agreements.asp (accessed 27 Dec. 2010) OLGR (2010) Banning order application by licensee. Sydney: New South Wales Office of Liquor, Gaming and Racing. http://www.olgr.nsw.gov.au/pdfs/L_F_BOL.pdf (accessed 28 Dec., 2010) OLGR (2011) About liquor accords. Sydney: New South Wales Office of Liquor, Gaming and Racing. http://www.olgr.nsw.gov.au/accords_about.asp (accessed 19 October, 2011). Pescod, A. 313 Drinking Banning Orders issued, confirms Home Office. Morning Advertiser, 27 November http://www.morningadvertiser.co.uk/City-News/313Drinking-Banning-Orders-issued-confirms-Home-Office (accessed 10 December, 2011) Pratten, J.D. & Bailey, N. (2005) Pubwatch: questions on its validity and a police response, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 17(4):359364. 22 Pratten, J.D. & Greig, B. (2005) Can Pubwatch address the problems of binge drinking? A case study from the North West of England, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 17(3):252-260. Room, R. (1976) [Drunkenness and the law: comment on ‘The Uniform Alcoholism and Intoxication Treatment Act’.] Journal of Studies on Alcohol 37:113-144. Room, R. (2004) Alcohol and harm reduction, then and now. Critical Public Health 14:329-344. Room, R. (2006) Advancing industry interests in alcohol policy: the double game. Nordisk Alkohol- & Narkotikatidskrift 26: 389-402. http://nat.stakes.fi/NR/rdonlyres/CECC1479-F603-4A55-B4D98761FDB534F8/0/NAT6_2006.pdf (accessed 17 Jan., 2011) Rosenqvist, P. & Takala, J.-P. (1987) Two experiences with lay boards: the emergence of compulsory treatment of alcoholics in Sweden and Finland. Contemporary Drug Problems 14(1):15-38. Sääski, J. (1960) Kontroll av kundernas inköp inom utminuteringen [On the control of retail liquor purchases]. Alkoholpolitik 3:111-115, 135-136. Schechter, E.J. (1986) Alcohol rationing and control systems in Greenland, Contemporary Drug Problems 13:587-620. Schrad, M.L. (2010) The Political Power of Bad Ideas: Networks, Institutions, and the Global Prohibition Wave. Oxford, etc.: Oxford University Press. Shepherd, J, (1994) Violent crime: the role of alcohol and new approaches to the prevention of injury. Alcohol and Alcoholism 29(1):5-10. Single, E., Giesbrecht, N. & Eakin, B. (1981) The alcohol policy debate in Ontario in the post-war era. In: Single, E., Morgan, P. & de Lint, J., eds. Alcohol, Society, and the State, 2: The Social History of Control Policy in Seven Countries, pp. 127-157. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation. Starke, A. (2010) Liquor laws into uncharted territory. The Shout: Hotel, Bar, Club and Liquor Industry News, 8 September. http://www.theshout.com.au/2010/11/01/article/Liquor-Laws-into-UncharteredTerritory/BSKYSFNRCC.html (accessed 29 Dec., 2010) Thompson, S. & Genosko, G. (2009) Punched Drunk: Alcohol, Surveillance, and the LCBO 1927-1975. Halifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing. Tigerstedt, C. (2000) Discipline and public health. In: Sulkunen, P., Sutton, C., Tigerstedt, C. & Warpenius, K., eds. Broken Spirits: Power and Ideas in Nordic Alcohol Control, pp. 93-112. Helsinki: Nordic Council for Alcohol and Drug Research, NAD Publication No. 39. http://www.nordicwelfare.org/filearchive/8/87240/39publikation.pdf (accessed 16 Jan., 2011) Voas, R.B., du Pont, R.L., Talpins, S.K., Shea, C.L. (2011) Towards a national model for managing impaired driving offenders. Addiction 106(7):1221-1227. 23 Watts, N. (2010) Liquor Accord serves life ban, The Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.) 6 Oct 2010. http://www.themorningbulletin.com.au/story/2010/10/06/liquoraccord-echoes-rockys-ban-of-warcon/ (accessed 28 Dec., 2010) Welch, J. (2010) Can I challenge a pub ban? Guardian (London), 30 April. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/libertycentral/2010/apr/30/challengepub-ban? (accessed 28 Dec., 2010) WA Police (2011) Barring Notices. Perth: Western Australia Police. http://www.police.wa.gov.au/Aboutus/News/BarringNotices/tabid/1787/Default.as px (accessed 10 December, 2011) Wood, D. (2011) Grog reforms over. NT News, June 27. http://www.ntnews.com.au/article/2011/06/17/243551_ntnews_pf.html (accessed 17 October, 2011) 15 Dec., 2011 24