L10A- Phonetic Alphabets (28 January, 2005)

advertisement

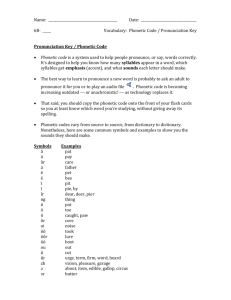

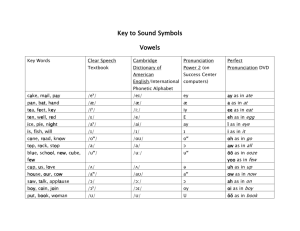

L10A- Phonetic Alphabets (28 January, 2005) In this course, we will be learning to use the phonetic alphabet developed by the International Phonetic Association. In this section, we look at some of the reasons why a special phonetic alphabet is necessary and then some of the background of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). We need the following as our guide: 1. Writing things the way they sound 1. How not to do it 2. Problems with using English spelling conventions 3. Ways to overcome the problem 2. The IPA 1. The International Phonetic Association 2. The International Phonetic Alphabet Writing things the way they sound The standard system used to write a language is called its *orthography* (from Greek stems: /ortho-/ 'correct', /graphy/ 'writing'). Even for languages whose writing systems are based on alphabets, the standard "correct" spellings often have little to do with how the words are pronounced. Phonetic alphabets are designed (and necessary) for writing down utterances in a way that records how they sounded. Ideally, someone who never heard the original utterance should be able to recreate it simply by reading the written transcription out loud. How not to do it Fiction writers will often try to give the impression that a speaker is using a different accent by deliberately misspelling some randomly chosen words. For example: Pets thim animals may be, an' domestic they be, but pigs I'm blame sure they do be, an' me rules says plain as the nose on yer face, 'Pigs Franklin to Westcote, thirty cints each.' An' Misther Morehouse, by me arithmetical knowledge two time thurty comes to sixty cints. (Ellis Parker Butler, "Pigs is pigs") 1 'Pears lak she should pay some 'tention to her fifth husban', or leastwise her fo'th, but she don'. I don' understan' wimmin. Seem lak ev'body settin' fire to somethin' ev'time I turn my back. Wonder any buildin's standin' in the whole gahdam United States. (James Thurber, "Bateman comes home") Why not There are several problems with trying to use ordinary English spelling conventions to suggest how a word is pronounced. Firstly, doing so usually has offensive connotations. Writers seldom use misspelling for the speech of characters they are trying to get you to respect. While the misspellings may help suggest that a character speaks "differently" (from whom?), it usually also implies that the character is stupid or illiterate. (This is especially obvious with misspellings like "sez" that suggest a pronunciation which is almost certainly identical to pronunciation used by the writer.) More importantly, English spelling conventions are not consistent enough to be used in a systematic phonetic transcription. a. The same letter or letter combination can refer to different sounds. o /low/ vs. /cow/ vs. /bow, row, sow/ b. c. The same sound can be written with different letters or letter combinations. o s/ou/nd, c/ow/, b/ough/ Different dialects pronounce the same word differently. Good only for English (at best) The writer of a phonetic transcription facing a particular sound would have to choose between a number of different possible symbols. The reader of a phonetic transcription facing a given symbol could never be sure of what sound it was intended to represent. There would be problems even if there were some consistency in how a symbol was used. The transcriber might say "the combination 'ay' always means the sound in the word 'day'", but would this be the word "day" as pronounced by a western Canadian, by an Australian, by a Londoner? Even if these problems could be solved, English spelling conventions would (for understandable reasons) only be useful in writing the sounds which occur in English -- they would be no help in writing sounds found in other languages (or in language-disordered children) which are not found in standard English. Overcoming the problems Several writing systems have been developed which are more concerned with how a word sounds than with how it has traditionally been spelled. 1. Shorthand systems (e.g., Pitman shorthand 2. Traditional dictionary keys 3. Informal transcription conventions 4. Specialized alphabets, e.g. 2 George Bernard Shaw's 'Proposed English Alphabet' the International Phonetic Alphabet Shorthand systems Many of the shorthand systems developed for English in the last couple of centuries (such as Pitman shorthand pictured here use the idea of writing down words the way they sound, rather than the way they are spelt -- a large motivation being the time saved in not writing silent letters. Traditional dictionary keys English dictionaries usually give the pronunciation of a word as part of its entry. In Webster's dictionary, for example, you will find that the pronunciation of /knight/ is "n&imacron;t" and /cat/ is "kăt". In order to understand these pronunciation entries, you have to learn what sounds are meant by symbols like "&imacron;" and "ă". As consistent as they can be made for a single dialect of English, both shorthand systems and the traditional dictionary pronunciation keys will suffer from the same problems as ordinary orthography when it comes to discussing the differences between dialects. Informal transcription conventions Professional linguists, particularly those in the North American tradition, have over the past century developed a collection of symbols for use in phonetic transcriptions. Many of these are identical to the symbols used in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), but there are also several differences. For example, the "sh" sound of English is written [esh] in the International Phonetic Alphabet, but was usually written &shacek; [&shacek;] by North American linguists. Many of these differences made it easier to type the symbols on a typewriter -- instead of leaving a space where an [esh] should have been and writing it in by hand later, you could type an ordinary [s] and only have to put the check mark on later. Unfortunately, this set of transcription conventions was never standardized. While some of the symbols were used the same way by almost everybody (e.g., &scheck;), most were not. If you read a particular symbol in a linguistics article, you could never be certain what sound it was supposed to represent. Specialized alphabets A more radical solution is to create an entirely new alphabet. Several proposals for new alphabets have been made over the centuries. One example is George Bernard Shaw's proposed alphabet for English. The only proposed alphabet which has achieved widespread use is the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), used by phoneticians, linguists, speech/language pathologists, and increasingly by dictionary makers and second language teachers. Source: http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/linguistics/russell/138/sec1/ipa1.htm 3