The question is

advertisement

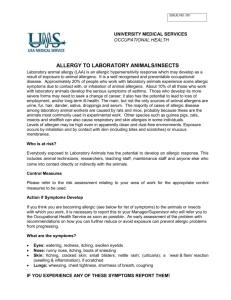

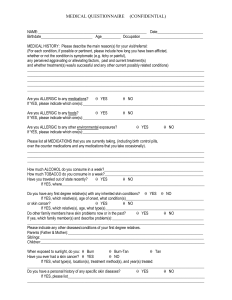

THE SAFE HANDLING OF LABORATORY ANIMALS ST. LOUIS UNIVERSITY (Revised 9-2008) POLICY Safety ranks equal in importance to all other objectives of the University. Safety is promoted and achieved through good facilities and equipment, the establishment and enforcement of safety rules, informed and trained personnel, and the use of appropriate personal protective equipment. General principles include, but are not limited to: * Each individual is responsible for safe work practices. * Don't take unnecessary risks. * Read posted signs and information. * Obey all safety guidelines. * Contact facility personnel with any questions or concerns. INTRODUCTION As a general rule, the incidence of zoonotic diseases (zoonosis = disease of animals transmissible to humans) is rather low among personnel exposed to laboratory animals. A complete listing of possible diseases is apt to produce a distorted impression of the actual danger. Some of the more common and serious diseases will be highlighted later in this document. . In general, health and safety matters relate to the species you work with and the frequency and type of contact. HAZARDS ASSOCIATED WITH ANIMALS Rodents and Rabbits Practically all of the smaller laboratory animals (e.g. mice, rats, rabbits, hamsters, guinea pigs, etc.) are procured from vendors having animal colonies free of human and animal pathogens (disease causing organisms). Rodents that are procured from non-vendor sources are subjected to a quarantine and testing program to ensure approved health standards are met. After receipt, these animals are usually maintained pathogen-free through use of proper control measures (e.g. Microisolator or ventilated caging, cage changing inside a Biosafety Cabinet (BSC)). Thus, the risk of contracting an infectious disease from a rodent or rabbit is extremely small. The most significant hazard associated with these animals is the possibility of developing or exacerbating an allergic condition. (See discussion of laboratory animal allergies). Dogs and Cats These animals are also obtained from USDA registered, Class A vendors (e.g. Marshall) where the animals are bred solely for research purposes. Therefore, their health status and vaccination history is known. The most frequent injuries associated with dogs and cats are bites, scratches and allergies. Swine Farm-type laboratory animals such as swine are purchased from varied approved vendors (Oak Hill, Sinclair). Care must be exercised when working with farm animals to avoid bites, scratches, kicks, and strains. Summary Thus, not all laboratory animals are guaranteed to be absolutely free of zoonotic diseases, although most can 1 be used safely if there is awareness of the potential risks and hazards and adherence to certain procedures. The purpose of this document is to describe appropriate procedures for working with animals in a safe manner. It describes procedures for human and animal health maintenance and some of the common zoonotic diseases of animals used in research at St. Louis University. PERSONAL HYGIENE 1. Husbandry personnel are issued scrubs and lab coats to wear. All personnel are required to wear proper personal protective equipment (PPE) in animal holding or procedure rooms. The requirements are posted on signage on each animal room door. Scrubs and lab coats are not permitted to be worn in public areas and never taken home. All work clothing in laundered on-site. 2. It is advisable to wear disposable gloves when handling any animal or related equipment. Sinks, soap, and hand towels are available in all animal rooms. Remove gloves and wash hands when leaving the room. 3. Whenever, bare hands, arms, neck/face, head become accidentally contaminated with animal blood, urine, feces, or hair. Such contamination should be removed as soon as possible by washing thoroughly with water and soap. When such contamination comes in contact with a mucus membrane (e.g. oral cavity, eyes, nasal cavity) it should be removed quickly by flushing with generous amounts of water. 4. Smoking is prohibited in all buildings on campus. 5. . Eating and drinking are permitted only in designated areas in the facility. SAFETY RELATED TO SANITATION 1. Floors, walls, sinks, and all fixed equipment should be kept uncluttered and clean. 2. Movable equipment should be properly secured when in use and stored. 3. When pests (insects, wild rodents) are noted, a facility supervisor or manager should be notified. He/she will arrange for the contract pest exterminator to rid the area of the pests. The unauthorized use of pesticides is prohibited and can be hazardous to personnel and research animals. 4. In the SLU facilities, it is acceptable to use only CM-approved antiseptics, disinfectants, and detergents. They must be used in accordance with the label directions. If used improperly, they can be ineffective and potentially hazardous. 5. Animal carcasses, waste bedding, and other biological wastes are best disposed of by incineration. Carcasses and other wastes should be carefully sealed in plastic bags and placed in the assigned refrigerated storage area. GENERAL SAFETY RULES * Wear appropriate protective clothing and use IACUC approved animal restraint techniques and equipment as instructed by CM personnel or the PI. 2 * Report all injuries immediately. A CM supervisor or Manager can provide you assistance and the appropriate report form. * Keep your work area uncluttered. Allow sufficient aisle space between cage racks and worktables. * Smoking is prohibited in all buildings on campus. * Eating and drinking are permitted only in designated areas in the facility. * Damaged or defective cages and racks should be set aside. Notify a supervisor so the equipment can be repaired or discarded. * Do not overload carts, obscure vision, or exceed weight capacity of transport carriers. * Do not use an incorrect transport carrier for the job * Broken glassware must be swept up with a brush/broom and discarded in a Sharps container. * Do not handle animals unless and until you have been thoroughly trained. BIOHAZARDOUS PROJECTS 1. Special containment rooms, designed for projects involving known hazardous agents, are available and assigned on a project basis. 2. Projects involving hazardous agents or materials have very strict requirements for protective clothing and procedures. Containment procedures are for the protection of personnel and other animals. Specific standard operating procedures will be posted and special training sessions required. 3. Generally, working with hazardous agents will require full body protection with appropriate clothing and other safety equipment. Project specific SOPs are developed in accordance with the approved IBC protocol. EMERGENCIES This includes all on-the-job injuries. When an employee is injured at work, he/she should immediately report the injury to a supervisor. The supervisor should assist the employee with filling out the Accident Form and send the employee to Employee Health or the Emergency Room (after normal working hours) for treatment. If any person is injured to the extent that he cannot be sent to Employee Health or the Emergency Room, the supervisor should: 3 1. Call 977-3000. (Campus DPS) 2. Advise where injured person is located and give person's name. 3. Describe extent of injury or illness. 4. Instruct the emergency personnel to go to the front desk, 1402 S. Grand. 5. Send someone to the front desk to meet the emergency personnel. When a supervisor, manager or other CM personnel are not available to assist, an injured employee should call or go directly to Employee Health or the emergency room. The injured person should notify a fellow employee if he/she leaves his work area to obtain medical treatment. OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH PROGRAM This program is for ALL St. Louis University personnel who are considered to have some occupational risk because of their involvement with laboratory animals. All employees are encouraged to participate in the SLU Occupational Health Program, which is collaborative effort between the Department of Comparative Medicine, Employee Health and Environmental Health and Safety. A policy titled “Occupational Health Program For Persons At Risk Relative To Exposure To Laboratory Animals “ outlines the tenants of the program and is disseminated to all new employees upon hiring. It is recognized that the Basic Program is the minimum required for all such personnel. Personnel in the department of Comparative Medicine are covered by a separate, more comprehensive program. Certain projects, particularly those involving hazardous agents or certain species, may necessitate more comprehensive tests, exams, or protective measures. These will be decided upon during the IBC protocol review process and implemented as appropriate. 1. Basic program, all personnel at risk a. b. c. d. e. Medical history evaluation. Tetanus immunization every 10 years. Tuberculosis screening (PPD) once, upon enrollment in program. Evaluation of University work related injuries and illnesses (referral to Employee Health). Written material entitled "The Safe Handling of Laboratory Animals" which includes information on zoonotic diseases. 2. Additional procedures, depending on species involvement a. Rodents and rabbits -- nothing additional b. Carnivore, livestock, feral species -- Basic program + 1) Rabies prophylactic immunization + biannual booster (projects involving random source dogs or cats or feral species only). 2) Q fever surveillance (projects involving sheep, cattle, or goats only). 3) Toxoplasmosis - awareness (cat projects only). 3. Comparative Medicine personnel receive all of the above with variations depending upon what species and/or hazardous agents they may be expose to. 4 ALLERGY TO LABORATORY ANIMALS The following is excerpted from the book "Occupational Health and Safety in the Care and Use of Research Animals." Allergies to animals are common. Laboratory Animal Allergies (LAA) are a common and important occupational health risk for persons who care for or work with them. Allergic reactions to animals are among the most common conditions that adversely affect the health of workers involved in the care and use of animals in research. Workers exposed to laboratory animals can be categorized into several risk groups. Risk of Developing Allergy to Laboratory Animals Risk Group Normal Atopic Asymptomatic Symptomatic Risk of allergic reactions to History laboratory animals No evidence of allergic disease Pre-existing allergic disease ~10% Immunoglobulin E antibodies to allergenic animal proteins Clinical symptoms on exposure to allergenic animal proteins Up to 100% Up to 73% 100% Comment 90% of normal group will never develop symptoms in spite of repeated animal contact Workers who become sensitized to animal proteins will eventually develop symptoms on exposure Risk of developing allergic symptoms of rhinitis, asthma, or contact urticaria with continued exposure is high 33% with chest symptoms; 10% of group might develop occupational asthma; even minimal exposure can lead to permanent impairment MECHANISMS OF ALLERGIC REACTIONS In the case of laboratory animal allergy, the route of exposure is most often due to airborne allergens. 5 Allergic Reactions to Laboratory-Animal Allergens Disorder Symptoms Signs Contact urticaria Redness, itchiness of skin, welts, hives Allergic conjunctivitis Sneezing, itchiness, clear nasal drainage, nasal congestion Allergic rhinitis Sneezing, itchiness, clear nasal drainage, nasal congestion Cough, wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath Asthma Anaphylaxis Generalized itching, hives, throat tightness, eye or lip swelling, difficulty in swallowing, hoarseness, shortness of breath, dizziness, fainting, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea Raised, circumscribed erythematous lesions Conjunctival vascular engorgement, cheminosis, clear discharge (usually bilateral) Pale or edematous nasal mucosa, clear rhinorrhea Decreased breath sounds, prolonged expiratory phase or wheezing, reversible airflow obstruction, airway hyper-responsiveness Flushing, urticaria, angioedema, stridor, wheezing, hypotension, shock Virtually all human beings are capable of developing allergic reactions; however, some individuals are more susceptible. These people (topics) are more likely to develop IgE antibodies to allergens owing to an inherited tendency. Persons with atopy often develop allergic diseases, such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis (eczema) when chronically exposed to allergens. SPECIFIC ANIMALS THAT CAN PROVOKE ALLERGIC REACTIONS Rats Rats are among the most commonly used laboratory animals and are responsible for symptoms in a large portion of people who have laboratory-animal allergy. The major sources of rat-allergen exposure appear to be urine and saliva of the animal. Mice Mice are another important source of allergen exposure of laboratory workers. The major mouse allergen is a urinary protein. Guinea Pigs Immunochemical studies have identified allergenic components in the dander, fur, saliva, and urine of guinea pigs. Rabbits Rabbits are used widely as laboratory animals and are a recognized cause of allergic symptoms in many workers. A major glycoprotein allergen has been described that appears to occur in the fur of the animals, 6 and minor allergenic components found in rabbit saliva and urine have been identified. Cats Domestic cats are kept as pets by many people, and sensitization can occur outside the laboratory environment. Furthermore, allergy to cats might predispose workers to the development of allergy to laboratory animals, such as mice and rats (Hollander and other 1996). There is a close link between immunological sensitization and development of asthma in people sensitive to cats (Desjardins and others 1993). Those with pre-existing sensitivity might encounter worsening of their symptoms and possibly develop asthma during the course of their work exposure. Dogs Like exposure to cats, exposure to domestic dogs outside the work environment can lead to sensitization and is also a risk factor for laboratory animal allergy. Birds Exposure to birds can cause rhinitis and asthma symptoms. Birds are also a potential source of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, a lung condition in which a pneumonia-like illness develops after repeated exposure to the antigen. PREVENTIVE MEASURES AND INTERVENTIONS Screening Programs Pre-employment screening evaluations are helpful in identifying and alerting persons who might be at risk for developing laboratory-animal allergy or asthma and educating them on appropriate protective measures. The presence of pre-existing allergic conditions might increase the likelihood of development of asthma in an occupational setting where there is exposure to laboratory animals. Because most people will not develop sensitivities beyond pre-existing conditions, this evaluation should not preclude employment. Personnel with identified pre-existing laboratory animal sensitivities/allergies should avoid repetitive exposure and be provided PPE to minimize the risk. Facility Design Ventilated cage dumping stations are utilized to minimize allergen exposure. Use of ventilated hoods (BSC’s) or workstations for cage emptying, cleaning and changing are utilized to minimize allergen exposure, Filter-top cages and ventilated caging have been shown to reduce concentrations of airborne allergens, compared with conventional open-top cages. This type of caging should be recommended when applicable. Work Practices Personnel with a history of allergies and particularly those with known sensitivities to animals are at highest risk and so should be especially sought out for education. 7 Personal Protective Equipment Surgical (cloth or paper) disposable masks are not effective in reducing exposure. The use of gloves, disposable gowns, shoe covers, and other kinds of protective clothing that are worn only in the animal rooms should be encouraged. Frequent hand washing is important and showering after work might be of value. At a minimum, for symptomatic workers, the use of an N95 respirator certified by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and properly fit tested by the SLU occupational health or employee health staff is required to control symptoms. ZOONOSES The term “zoonoses” is applied to those diseases which are naturally transmitted from animals to humans. A. It is important to note that the transmission of zoonotic disease in the laboratory-animal environment is uncommon, despite the number of animal pathogens that have the capacity to cause disease in humans. B. The primary reasons for such a low incidence is that the laboratory-animal industry has had much success in providing high-quality laboratory animals of defined health status for use in research. For purposes of this discussion, we will exclude diseases produced by non-infective agents such as toxins and poisons. Only some of the more important zoonoses are described below. Most discussions of zoonoses are organized by agent category (e.g. virus, bacteria, etc.). We have arranged our discussion by the category of species used in the laboratory. Further, we emphasize that we are only highlighting a few common or important diseases. Rats, Mice, Hamsters, Guinea Pigs, and Rabbits The vast majority of these animals are produced by approved vendors in highly controlled commercial facilities and are free of all pathogens and, therefore, pose minimal risk. There are two diseases that need to be mentioned, primarily related to animals raised in investigator-based breeding colonies. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Reservoir and Incidence - Lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCM) virus is a member of the family Arenaviridae, which consists of single-stranded-RNA viruses with a predilection for rodent reservoirs. Human infection with LCM associated with laboratory-animal and pet contact has been recorded on numerous occasions. Mode of Transmission - The LCM virus produces a pantropic infectin under some circumstances and can be present in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, nasophayngeal secretions, feces, and tissues of infected natural hosts and possibly humans. Bedding material and other fomites contaminated by LCM-infected animals are potential sources of infection, as are infected ectoparasites. Slinical Signs, Susceptibility, and Resistance - Humans develop an influenza-like illness characterized by fever, myalgia, headache, and malaise after an incubation period of 1-3 weeks. 8 Diagnosis and Prevention - Prevention of this disease in the laboratory is achieved through the periodic serological surveillance of new animals that have inadequate disease profiles and of resident animal colonies at risk and through screening for the presence of LCM in all tumors and cell liens intended for animal passage. Rat-Bite Fever Reservoir and Incidence - Rat-bite fever is caused by either Streptobacillus moniliformis or Spirillum minor, two microorganisms that are present in the upper respiratory tracts and oral cavities of asymptomatic rodents, especially rats. Mode of Transmission - Most human cases result from a bite wound inoculated with nasopharyngeal secretions. Clinical Signs, Susceptibility, and Resistance - In Strep. moniliformis infections, patients develop chills, fever, malaise, headache, and muscle pain and then a maculopapular or petechial rash most evident on the extremities. Diagnosis and Prevention - Proper animal-handling techniques are critical to the prevention of rat-bite fever. Dogs, Cats, and Pigs As mentioned previously, only purpose-bred dogs and cats from USDA registered, Class A vendors are used at Saint Louis University. As such, the potential risk for acquiring a zoonotic disease is minimal. A few diseases will be discussed. Rabies is discussed in the feral animal category. Campylobacteriosis Reservoir and Incidence - Organisms of the genus Campylobacter have been recognized as a leading cause of diarrhea in humans and animals in recent years, and numerous cases involving the zoonotic transmission of the organisms in pet and laboratory animals have been described. Mode of Transmission - The organism is transmitted by the facal-oral route via contaminated food or water or direct contact with infected animals. Clinical Signs, Susceptibility, and Resistance - Campylobacters produce an acute gastrointestinal illness, which in most cases if brief and self-limiting. Diagnosis and Prevention - Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing, personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent the transmission of the disease. Fungal Diseases Dermatomycosis Ringworm Reservoir and Incidence - The dermatophytes have a cosmopolitan distribution; some dermatophytes have a regional geographic concentration. These organisms cause ringworm in humans and animals, which continues to be common among dogs, cats, and livestock. Mode of Transmission - The transmission of dermatophyte infection from humans to animals is by direct skinto-skin contact with infected animals or indirect contact with contaminated equipment or materials. Infected animals can have no, fe, or difficult-to-detect skin lesions that result in transmission to unsuspecting persons. 9 Clinical Signs, Susceptibility, and Resistance - Dermatophytes that are better adapted to humans produce focal, flat, spreading annular lesions that are clear in the center and crusted, scaly, and erythematous in the periphery. Lesions often are on the hands, arms, or other expose areas, but invasive and systemic infections have been reported in immunocompromised people. Diagnosis and Prevention - The definitive diagnosis of dermatomycosis is achieved by fungal culture and identification, but lesions appearance and scapings, of active lesions cleared in 10% potassium hydroxide and examined microscopically for fungal filaments can be used for a tentative diagnosis. The use of protective clothing, disposable gloves, and other appropriate personal-hygiene measures is essential to the reduction of this zoonosis in a laboratory-animal facility. Cat-Scratch Fever Reservoir and Incidence - Bartonella henselae, a newly described rickettsial organism, has been directly associated with cat-scratch fever and bacillary angiomatois. The organism has been isolated on fleas that fed on infected cats, and fleas have been shown to be capable of transmitting the organism between cats. Although cat-scratch fever usually has bee associated with the scratch or bite of a young cat, other animals have been implicated, including dogs, monkeys and porcupines. Mode of Transmission - Of patients with the disease, 75% report having been bitten or scratched by a cat, and over 90% report a history of exposure to a cat. Clinical Signs, Susceptibility, and Resistance - The disease begins with inoculation of the organism into the skin of an extremity, usually a hand or forearm. A small erythematous papule appears at the site of inoculation several days late and is followed by vesicle and scab formation. The lesion resolves within a few days to a week. Diagnosis and Prevention - Isolation of the causative organism from the blood, a cutaneous lesion, or biopsy material is required for a definitive diagnosis of cat-scratch fever. The use of proper cat-handling techniques and protective clothing should minimize the likelihood of personnel exposure to the organism of cat-scratch fever. Toxoplasmosis Reservoir and Incidence - Toxoplasma gondii is a coccidian parasite with a worldwide distribution among warm-blooded animals. Wild and domestic felines are the only definitive hosts of this organism; they are infected by one another or through predation of an intermediate host, and they support all phases of the t. gondii life cycle in their intestinal tract, although numerous other tissues are also involved in feline toxoplasmosis. Mode of Transmission - Infection results from the ingestion of infectious oocysts in food, water, or other sources contaminated by feline feces. Clinical Signs, Suceptivility, and Resistance - Toxoplasmosis generally produces an asymptomatic or mild infection with fever, myalgia, arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, and hepatitis. Toxoplasma infection can have severe consequences in pregnant women and immonologically impaired people. In a pregnant woman with a primary infection, rapidly dividing tachysoites can circulate in the bloodstream and produce a transplacental infectin of the fetus. Diagnosis and Prevention - Toxoplasmosis can be diagnosed by finding the organism in clinical specimens. Personnel should practice appropriate personal-hygiene practices and maintain rigorous sanitation of an animal facility to prevent exposure to toxoplasma. Unless they are known to have antibodies to toxoplasma, 10 pregnant women should be advised of the risk associated with fetal infection. Cat feces and litter should be disposed of promptly before sporocysts become infectious, and gloves should be worn in the handling of potentially infective material. Sheep, Goats, and Other Ruminants There is a much higher likelihood of injury as a result of a kick or muscle strain than acquiring a zoonotic infection. Q-Fever Reservoir and Incidence – Q-Fever is caused by the rickettsial agent Coxiella burnetii. Infection is widespread within the domestic-animal cycle, which includes sheep, goats, and cattle. Cats, dogs, and domestic fowl also can be infected. The prevalence of the infection among sheet is high throughout the United States, and sheep have been the primary species associated with outbreaks of the disease in laboratory-animal facilities. However, an outbreak of Q fever with one death in a human cohort exposed to a parturient cat and her litter and cases of the disease associated with exposure to rabbits indicate that other species should not be overlooked as possible sources of the infection in the laboratory animal environment. Mode of Transmission - Humans usually acquire this infection via inhalation of infectious aerosols, although transmission by ingestion has been recorded. The organism is shed in urine, feces, milk, and especially birth products of domestic ungulates, which generally are asymptomatic. The organism is resistant to desiccation and persists in the environment for long periods, contributing to the widespread dissemination of infectious aerosols. The importance of those factors was evident in outbreaks of the disease associated with the use of pregnant sheet in research facilities in the United States when personnel became infected along the routes of sheep transport and in the vicinity of sheep surgery from contact with soiled linens. Slinical Signs, Susceptibility, and Resistance - The disease in humans varies widely in duration and severity, and asymptomatic infection if possible. The disease often has a sudden onset with fever, chills, retro bulbar headache, weakness, malaise, and profuse sweating. Acute pericarditis and acute or chronic granulomatous hepatitis also have been reported. Persons with valvular heart disease should not work with C. burnetii. Diagnosis and Prevention - Serological methods available for the detection of a rise in specific antibody between acute and convalescent samples include microagglutination, immunofluorescent, complement fixation (CF) and ELISA tests. Recommendations for the control of Q fever in a research facility are available and should be applied rigorously in surgical, laboratory, and housing areas used for sheep. Physical barriers or air-handling systems, the appropriate use and disposal of protective clothing, and the use of disinfectants in the sanitation and waste-management programs minimize the risk of exposure. Orf Disease (Contagious Ecthyma and Contagious Pustular Dermatitis) Reservoir and Incidence - Orf disease is a poxvirus infection that is endemic in many sheep flocks and goatherds throughout the United States and worldwide. Ergonomic Considerations Pre-employment screening evaluations are helpful in identifying and alerting persons who might be at risk for developing musculoskeletal problems or repetitive motion injuries. The presence of pre-existing conditions might increase the likelihood of development of injuries in an 11 occupational setting where there is exposure to such risks. Personnel with an identified pre-existing condition should avoid activities that may exacerbate a condition. Several safeguards have been put into play to reduce the risk of injuries or conditions that may develop or be exacerbated by routine job duties. Examples of safeguards include, but are not limited to: 1. 2. 3. 4. Pre-employment screening by employee Health. Evaluation of workspaces by an ergonomic specialist upon request. Evaluation of work practices by an ergonomic specialist upon request. Reduction in heavier glass /metal equipment and replacement with lighter plastic products (e.g. water bottles) 5. Purchasing of adjustable Cage Changing stations and Biosafety Cabinets to accommodate differing employee heights. 6. Limiting the number of cages a single technician can change in a normal 8-hour work day. (< 200/technician/8 hour work day) 7. Transition to ventilated caging which decreases the frequency od cage handling. References 1. Occupational Health and Safety in the Care and Use of Research Animals. National Academy Press, Washington DC, 1997. 2. Occupational Health and Safety in Biomedical Research. ILAR Journal V 44(1), 2003. 3. Laboratory Animal Allergy. ILAR Journal V42 (1), 2001. 4. Hankenson FC, Johnston NA, Weigler BJ, DiGiacomo RF. Zoonoses of occupational health importance in contemporary laboratory animal research. Comparative Medicine. 2003; 53(6):579-601. 5. Ergonomic considerations for Laboratory Animal Personnel. ILAR Journal V44 (1), 2003. 12