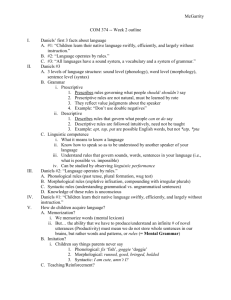

Syntax and sociolinguistics

advertisement

From Joachim Jacobs, Arnim von Stechow, Wolfgang Sternefeld and Theo Vennemann (eds) 1995.

Syntax. An International Handbook of Contemporary Research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. 151428. This article is by Richard Hudson.

84. Syntax and Sociolinguistics.

1. Introduction

2. Defining 'Sociolinguistics'

3. Syntactic Constraints on Code-Mixing

4. Syntax in Multilingual Communities

5. Syntactic Variation in a Creole Continuum

6. Syntactic Peculiarities of Dialects or Registers

7. Social Influences on Syntax

8. Quantitative Approaches to Syntactic Analysis

9. Quantitative Methods and GrammaticalTheory

10. The Locus of Grammars and of Variation

11. References

1 Introduction

Sociolinguistics is the study of linguistic structures in relation to social structures. Syntactic

structures have so far received less attention than phonological structures, but sufficient work has

been done on them to show that the sociolinguistic approach promises to offer some valuable

insights. At the same time it is fair to admit that at present the promises are hardly more than that

(except in a few rather specialised areas listed below): there have been few sociolinguistic studies

to match in sophistication the early syntactic work of William Labov on copula deletion and

negative concord (1972). The main contribution of sociolinguists has been to study varieties of

language which theoretical and descriptive linguists tend to ignore, rather than to explore the

consequences of sociolinguistic findings for theories of syntax.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, this research focus has allowed sociolinguistic work on syntax to be

ignored by most syntacticians. It would be fair to say that this work has had no influence at all on

the most popular theories of syntax such as the three described in Sells (1985) and Horrocks

(1987), namely Government-Binding Theory, Lexical Functional Grammar and Generalised Phrase

Structure Grammar. It is true that some theories attempt to take account of one particular strand of

sociolinguistics, the study of discourse - two such theories are Systemic Grammar (Halliday 1985)

and Functional Grammar (Dik 1978) - but these theories in turn are generally ignored by followers

of other theories, and in any case it is debatable to what extent their analyses achieve their stated

goals.

The aim of this article is to outline the part that syntax has played so far in sociolinguistics,

focussing where possible on methods or findings which are likely to be of interest to general

syntacticians. We start with a brief survey of the kinds of activity that are commonly classified as

'sociolinguistics'.

2 Defining 'Sociolinguistics'

On the one hand, sociolinguists identify themselves by their METHODS - they typically study

tape-recorded texts, which have been collected with some attention to the possible influences of

social variables, and they typically analyse these texts in a quantitative way. One reason for

analysing texts in this way is in order to find statistical evidence that social variables influence

linguistic variables, but the texts are typically subjected to other, more purely linguistic, processing

as well, in which the aim is to find ways in which the linguistic context influences a linguistic

variable. For example, Labov (1972) studied the use of sentences like Clarence my friend (meaning

'Clarence is my friend') in New York, and investigated the influence not only of social variables

(such as the speaker's race) but also of the linguistic environment (e.g. whether the predicate was a

noun-phrase or an adjective-phrase). It is clear that there is nothing especially 'social' about the

latter work, but it counts as 'sociolinguistic' because of the methods used. Another characteristic of

sociolinguistic work is its SUBJECT MATTER. Sociolinguists typically study varieties of language

whose social prestige is low - non-standard dialects dominated by a standard dialect (notably

English), subordinate languages spoken by immigrant or other minorities, and pidgins or creoles.

Once again this focus follows from the interest in social influences on language behaviour speakers of such varieties often have some knowledge of the dominant variety, and may combine

forms of the two varieties in interesting ways - but it is of course possible to study any such variety

with regard to nothing but its own internal structure. Moreover, it could be studied without the use

of quantitative methods. In either case, the work would still be considered by many to be an

example of 'sociolinguistics', in contrast with 'ordinary' grammatical research (whose focus is still,

regrettably, very much on standard languages). By this interpretation, then, a study of (say) relative

clauses in a non-standard dialect would count as sociolinguistics, whereas a similar study relating

to a standard dialect would not. It is clear that the concept 'sociolinguistics' has all the

characteristics of a set of 'family resemblances' - all its instances share some properties with other

instances, but there are no properties which are shared by all instances (which would not be shared

equally by other branches of linguistics). Whatever the merits of interpreting the term in this way,

the fact is that this is how it is often interpreted, so I too shall take it to include all these things.

However, I shall ignore one important area of work which is often included in sociolinguistics, the

study of discourse.

3 Syntactic Constraints on Code-Mixing

We start with one of the most dramatic challenges to familiar assumptions about grammmars. In

many multilingual communities code-mixing is normal - that is, speakers often change languages in

mid-sentence. For example, Pfaff (1979) quotes attested utterances like (1).

(1)

No van a bring it up in the meeting.

Here the first three words are in Spanish, meaning 'They are not going to', but the rest of the

sentence, in English, has a syntactic structure which fits these Spanish words.

Examples like these are sufficiently interesting in their own right, since they raise important issues

about the cross-linguistic identification of categories. For example, in Spanish, ir a, 'be going to', is

followed by an infinitive (a morphologically marked form of the verb); but in (1) it is followed by

the uninflected English word bring, so it seems reasonable to assume that this too counts as an

infinitive - i.e. that there is some psychologically real sense in which bring and a Spanish verb like

com-er, '(to) eat', belong to the same category. Even more interestingly, however, it turns out that

people who use code-mixed utterances like (1) can also pass judgment on their relative

acceptability, in just the same way that native speakers can judge the acceptability of an unmixed

utterance (e.g. Sobin 1984, Aguirre 1985). Moreover, when these judgments are taken in

conjunction with sample texts, there seems to be a good deal of agreement among speakers about

the kinds of mixing which are permitted. It is possible to generalise the judgments in terms of

syntactic structures and to derive general constraints on code-mixing - i.e. rules about the positions

in sentence structure where it is permissible to switch from one language to the other. This finding

has given rise to a lot of research (amply documented in Bokamba 1987), covering a wide range of

language-pairs. In each case the research has produced rules which control mixing in some

particular community, though for some communities different researchers have found different

rules by using different methods - for instance, there is disagreement as to whether Spanish-English

bilinguals allow mixing within a noun-phrase, so that an attributive adjective and its noun head are

in different languages. Pfaff (1979), using recordings of spontaneous speech, concluded that this

was possible only if the position of the adjective was permitted by both Spanish and English; which

means that it must precede the noun, and must belong to the small list of adjective-types which can

occur in that position in Spanish, as in (2).

(2)

mi unico pleasure 'my only pleasure'.

In contrast, Sobin (1984) asked bilingual speakers to judge prepared examples, and found that they

accepted examples which infringed Pfaff's generalisation - e.g.examples in which an English colour

adjective followed the noun. At the same time, his judges did not indiscriminately accept all

examples, and his research confirmed the general conclusion that there are systematic limits to

code-mixing. Reasssuringly, Sobin's findings seem to support those of Poplack (1980), based on

methods similar to Pfaff's. Of course, it is always possible that different Spanish-English bilingual

communities apply different rules, and that these researchers are all right, but with respect to

different communities.

One of the interesting questions that arises in this area is whether there is any syntactic evidence for

the asymmetrical relation between the two languages - syntactically definable boundaries where it

is permissible to switch languages in one direction but not in the other. There is good evidence for

such asymmetries in some communities; for instance, Bautista (1980) reports that Tagalog-English

mixing does not allow an English complementiser to be followed by a Tagalog word, though the

reverse switch is possible. Similarly, the data reported by Keddad (1986) can be interpreted as

showing that in Algeria French-Arabic mixing is controlled by the general principle that an Arabic

noun cannot be used as a dependent of a French word, though the reverse is permitted; for example,

switching from Arabic to French is not permitted between a subject and verb, though it is between

verb and object. However it is also worth noting that some of the most detailed and thorough

analyses have found no clear evidence for asymmetries, so they may exist in some communities but

not in others. It would be wrong to assume in advance that in every code-mixing community one

language is recognised as the 'matrix' within which mixing takes place (Schmid 1986).

Code-mixing may provide an extra source of evidence for deciding among competing analyses for

a construction, to which the analyst can turn when analysing one or the other of the languages

concerned. We have already noted that mixing suggests strongly that there is a psychologically real

identity between some grammatical categories in different languages. The detailed patterns of

mixing can be used further to defend particular analyses. For example, Blake (1987) argues that

English infinitival to is an instance of the (Government-Binding) category INFL, whereas the

corresponding Spanish word a is a preposition, on the basis of observed patterns of mixing between

Spanish and English (to may be followed by a Spanish infinitive, and a by an English infinitive - as

in our example (1) - but a Spanish verb cannot be followed by to). Whatever the merits of these

arguments, it is clear that code-mixing data provides a potentially rich source of evidence for

linguistic analysis (Woolford 1983).

The most general, and presumably the most important, factual question is whether all or any of the

constraints on code-mixing are universal. Opinion is sharply divided at present but according to

Bokamba (1987), the literature to date does not contain any universal constraints: different

constraints apply to different language-pairs. Various rules and principles have been claimed to be

universal, but the data-base has generally consisted of only a very small sample of language-pairs

and the claims are easily refuted on the basis of other pairs. For instance, according to Sciullo et al.

(1986), switching between subject and verb should always be easy, but Muthwi (1986) reports that

switching between English and Kalenjin is not permitted at all in this position.

These differences suggest, then, that the constraints are learned. If this is right, then the familiar

question arises as to how such things can be learned, given that the only available evidence is

negative. It is also important to note that at least one study (Lederberg et al. 1985) claims to show

that judgment patterns concerning code-mixing cannot be learned because the same patterns can be

produced by different judges whether or not they are members of a community in which codemixing is permitted.

The facts about code-mixing raise important questions for grammatical theory. It seems to be

generally agreed that code-mixers can avoid mixing (e.g. when talking to a monolingual), so they

clearly know which constructions and items belong to which language. Does this mean that they

have two separate grammars from which they draw, or a single grammar in which each element is

tagged for its language? Indeed, is this a meaningful question? In either case, what status do the

constraints on code-mixing have: part of some grammar or part of some kind of data-base for

pragmatics or processing? Various suggestions have been made, both formal (e.g.

Sankoff/Mainville 1986) and psycholinguistic (e.g. Sridhar/Sridhar 1980), but we are clearly a long

way from working through the implications of these facts for syntactic theory.

4 Syntax in Multilingual Communities

Code-mixing is not the only interesting phenomenon which is found in multilingual communities.

Other possibilities include important syntactic change in one or the other of the languages

concerned, and the creation of altogether new languages. The first of these possibilities falls into

the domain of historical linguistics, which is covered elsewhere in this encyclopedia, but it is worth

mentioning that sociolinguistics has an important contribution to make through the study of

contemporary multilingual communities and their social structures. This kind of work promises to

throw light on the mechanisms by which syntactic change takes place.

A particularly interesting example of this kind of work is the study of a small village in India called

Kupwar by Gumperz and Wilson (1971). The inhabitants of Kupwar are divided into castes, each

of which has one of three languages (Marathi, Urdu, Kannada) as its language. However, the castes

need to communicate with one another and bilingualism or trilingualism is common. What is

interesting is that although these languages have coexisted in Kupwar for centuries, their

vocabularies are still completely separate. One assumes that this can be explained functionally, in

terms of the need to symbolise the differences between castes. As far as syntax is concerned, on the

other hand, the differences between the languages have been grossly reduced. For example,

Kannada normally has a zero copula (i.e. no verb at all in sentences like 'John (is) my friend'),

whereas Urdu and Marathi have an overt copula; but the Kannada of Kupwar too has an overt

copula. It is interesting to speculate on the causal connections between these changes and codemixing, which is presumably less constrained the more similar the languages concerned are in their

syntax. It is also interesting to notice how commonly syntactic patterns are borrowed from one

language into another, provided the communication patterns between their speakers are sufficiently

intensive (Hudson 1980,59ft).

An even more dramatic consequence of the coexistence of two languages in one community is the

creation of a third language, combining the lexicon of one with the syntax of the other. This is

reported (Muysken 1981) to have happened in Ecuador, where a newly created language called

'Media Lingua' has the syntax of Quechua, but a vocabulary which is 90% Spanish. More precisely,

the voacabulary is 90% Spanish with respect to forms only, but the meanings and morphology (and,

one assumes, syntactic valency information) remain Quechua. Once again, most interesting

questions arise in connection with the formal and psychological relations among the grammars

concerned - for example, is Media Lingua a completely separate grammar, or is it just a set of

general principles for exploiting the grammars of Quechua and of Spanish?

The case of Media Lingua is somewhat unusual. A much more common example of a new

language being created in a multilingual situation is the birth of a PIDGIN language. These differ

from the case of Media Lingua in being, at least in their origins, much simpler and smaller than any

of the languages on which they are based. Rather interestingly, one of the main simplifications is

the total abandonment of inflection, even when this is used by all the source languages. Less

surprisingly, perhaps, early pidgins make no syntactic provision for relatively complex structures

such as subordinate clauses. If a pidgin is used only for very simple transactional purposes it is

possible to dispense with such things. Pidgin languages have been widely studied (Holm 1988), and

this work has generated some interesting questions for grammatical theory. Perhaps the most

general question is, once again, whether there are any universals of pidgin syntax, and if there are,

how they can be explained. For example, it is very common for pidgin languages to have a zero

copula (Ferguson 1971). Why should this be so? Another important set of questions arises about the

ways in which pidgins develop if the functional demands on them are expanded: is there a universal

sequence in which communicative needs are filled, or a universal set of ways in which they are

filled? For instance, the need for relative clauses can be met in various ways, but do pidgins all tend

to follow the same route as they change into creoles, by acquiring native speakers (Sankoff/Brown

1976, Romaine 1984)?

5 Syntactic Variation in a Creole Continuum

When a pidgin is created, there is typically one language which is dominant as the model for its

vocabulary - often a European language, because of colonialism - but its syntax may be radically

different from that of this language, showing heavy influence from the indigenous languages. When

it is learned as first language by the offspring of pidgin-speaking parents these syntactic

characteristics naturally persist, though the grammar may be expanded in the ways just alluded to.

Because of the historical circumstances under which pidgins and creoles arise, it is often the case

that the creole coexists with the dominant language on which the original pidgin was based. The

creole is spoken by poor people, and the dominant model by rich people in the same country.

Because of this social difference between them sociolinguists call the creole the 'basilect' and the

dominant model the 'acrolect'. For example, in many Caribbean countries the acrolect is (more or

less) standard English, while the basilect is an English-based creole. What makes this

sociolinguistic situation interesting for syntacticians is that the relative similarity between the

basilect and acrolect allows intermediate varieties to develop - which would not be possible if the

coexisting languages were completely different languages. The result is a continuous spectrum of

grammar between the basilect and the acrolect, known as a 'creole continuum'. As we have seen,

the syntactic differences between acrolect and basilect may be considerable, but the semantic

systems of the two varieties can also differ in fundamental ways - e.g. according to Bickerton

(1975) the basilect in Guyana shows anteriority (temporal relations to some reference-time), but not

deictic tense, whereas the converse is true of the acrolect (standard English). Where grammars

differ in such fundamental respects, but are linked by a chain of intermediate grammars, we are

likely to learn a great deal about the nature of grammar by studying the links between them.

The distance between acrolect and basilect can be illustrated by the roughly synonymous pair of

sentences in (3), taken from Winford (1985).

(3)

a Who do I want to go?

b A hu mi waan fi go?

Some of the differences are quite superficial

- e.g. the lack of t on waan - but others are much more significant:

the initial particle a, often used to markthe focus;

the lack of surface 'case' even in pronoun forms;

the lack of subject-auxiliary inversion inquestions.

As for the last two words, fi go, Winford argues persuasively that these do not correspond to the

standard to go, but constitute a finite clause (whose subject position isempty), fi being a modal

auxiliary. In standard English, of course, want does not allow a finite clause as complement.

The existence of intermediate varieties - 'mesolects' – provides a natural test-bed for a number of

issues in grammatical theory. What is (or should be) the status of the notion 'language', given that

by any standard definition of 'same language' every adjacent pair of mesolects must belong to the

same language, and therefore the same must be true of the basilect and acrolect too? In particular, is

it possible to believe that all dialects of (say) English share a 'common core' of syntax? Secondly,

what do the mesolects tell us about the relations among the elements of the grammar? Does the

order in which acrolectal features give way to basilectal ones relate in any way to their

interrelations in the grammar?

The discussion so far has accepted the claim (Bickerton 1975) that there is basically a single 'route'

from basilect to acrolect. However, this has been denied by a number of creolists (e.g. Washabaugh

1977, Edwards 1985), who find that this view oversimplifies the sociolinguistic facts considerably.

According to these scholars there are many independent dimensions of variation, and not just one.

This claim adds to the interest of creole continuums by reducing their uniqueness.Other societies

show multidimensional variation, as we shall see in section 7, so it should be easier to generalise

from creole continuums. Somewhat similar questions arise in connection with 'pidgin continuums',

such as those found in Western Europe among migrant workers. Thus the pidgin German of

Turkish 'Gastarbeiter' ranges from a minimal command of a few words to something approaching

German (e.g. Klein/Dittmar 1979). However this situation seems likely to throw less light on

normal syntax than the much richer and more stable grammatical systems found in creole

continuums.

6 Syntactic Peculiarities of Dialects or Registers

According to our definition of sociolinguistics, the study of dialects, and especially of low-prestige

dialects, is part of it. Factual information about such dialects is an important corrective to the

tendency for syntacticians to take account only of standard dialects. It is all too easy to draw

general and fundamental conclusions about the basic structure of a language on the basis of facts

which turn out not to apply generally to all dialects of the same language. For example, the analysis

of the English auxiliary verb system in Chomsky (1957) rested, inter alia, on the assumption that

modal verbs could not be combined with one another. This analysis was generally accepted in

Transformational Grammar for more than two decades, and is still the source of much of current

theorizing, via the abstract INFL node of Government-Binding Theory (Sells 1985, Horrocks

1987). However, the original analysis would never have been proposed if Chomsky had spoken

Scots English, since double (or even treble) modals are permitted there (Miller/Brown 1982), as in

(4).

(4)

He will can come.

The reason why differences between dialects are of special interest to grammarians is that the

dialects concerned are likely to be similar in other respects. Thus the facts about Scots are highly

relevant even to a grammar which claims to describe only standard English because it would be

hard to explain the differences in terms of general typological differences - unless of course there is

clear evidence that the dialects concerned are indeed different in some fundamental respects. In the

absence of such evidence we ought to be able to write grammars for the two dialects which are

different in only very specific ways - in terms of the valency requirements of particular modal

verbs, for example. Otherwise we have no explanation for all the similarities between them. We

should be especially suspicious of any analysis of one dialect which presents some fact about it as

the automatic consequence of a basic theoretical assumption, when the same fact does not apply to

a closely related dialect. A noteworthy example of this danger is the discussion of so-called 'thattrace' effects - the impossibility, in standard English, of extracting a subject across the

complementiser that as in (5).

(5)

%Who do you think that _ came?

Various attempts have been made to show how this fact follows from general typological properties

of English plus very general assumptions about the nature of grammatical structure; but these

attempts must all be wrong because there are dialects of English, spoken in the Ozarks, which do

allow structures like (5) (Sobin 1987). Until there is evidence for major typological differences

between these dialects and others, it is fair to assume that the differences are rather specific

(Hudson 1986).

The examples quoted so far could easily be multiplied. For example, recent discussions of English

dialects have turned up the following facts, all of which are surprising if one's main experience has

been in standard English:

Some dialects (spoken by Irish people and black Americans, but probably originating in the

South of England) show explicitly whether an event happened once or habitually, by using do

before the verb in the latter case; and be's can be used, as the inflected present of be, to indicate

habituality (Fasold 1969, Harris 1984, 1986, Bailey/Maynor, 1985).

In Scots English (Romaine 1980) relative clauses are introduced almost exclusively by that,

rather than by relative pronouns that begin with wh- (who, which, etc.). The word that can even

be used with 's, as a possessive, as in (6).

(6)

The man that's hat was blown off ran after it.

Structures like this suggest strongly that that is a pronoun in the dialects concerned, and not just a

complementiser.

The interest of examples like these is not just philological, but structural: they show that quite

major differences between varieties can still be limited to quite specific parts of the language

system. They are relevant to any discussion of how best to analyse the structures concerned, in

either of the dialects concerned.

Points similar to those just made in relation to dialects can also be made about REGISTERS varieties of language defined in relation to the ways in which they are used, such as 'high-level

academic writing about linguistics' or 'popular journalistic radio commentary on sport'. Differences

in syntax seem especially important for distinguishing registers (more so, for example, than

phonological differences, whose main domain is in distinguishing between dialects). To take just

one recent example, Bell (1985) discusses phrases like (7).

(7)

controversial cancer therapist Milan Brych

This example has a structure which is not permitted in ordinary speech or writing, because of the

absence of an article. Stylistically restricted registers like this cannot be dismissed as performance

errors, because they are obviously learned and systematic. Nor can they be ignored as marginal to

ordinary language, when linguists devote so much attention to other constructions which are

presumably much more peripheral to most people's ordinary language experience, such as 'gapping'

(8).

(8)

John invited Mary, and Bill, Sue.

Sociolinguists subsume the concepts 'dialect' and 'register' under the general term 'variety'. Any

variety differences of the kind discussed here are a challenge to the syntactician, whether

descriptive or theoretical, because they force a decision about what should be included in a

grammar, which in turn requires a decision about the ontological status of the grammar. In

particular, if the grammar is intended to be a psychologically plausible model of a speaker's

knowledge, then it clearly must cover the full range of registers known to a speaker (especiallyif

the latter is idealised as knowing the language perfectly). But if that decision is taken, some means

has to be found to distinguish the registers from one another, because these distinctions are also

known to native speakers.

7 Social Influences on Syntax

The notion 'variety' is rather a crude and unsatisfactory basis for characterising the ways in which

syntactic constructions can differ socially. It is unsatisfactory because of the considerable overlap

between varieties (Hudson 1980). Quantitative analysis of syntactic variation (described in the next

section) has shown that there is at least a strong tendency for constructions to be unique in their

social relations - some constructions are closely associated with formality of style, others with

social status of speaker, others with sex of speaker, and so on through a wide variety of quantitative

combinations and permutations of different social influences. A good example of the research

which shows this kind of patterning is reported in Cheshire (1982a, 1982b). The speakers studied

were a group of teenagers in Reading, in the south of England. One of the constructions studied

was the use of 'negative concord' - sentences like (9).

(9)

I'm not going nowhere.

This turned out to be associated closely with what Cheshire calls 'vernacular loyalty' i. e. roughly

speaking, its use was associated with delinquency. This was equally true both for the girls and for

the boys. Another construction was the use of what (rather than that) to introduce relative clauses,

as in (10).

(10)

There's a knob what you turn.

This was also used to mark vernacular loyalty, but only for boys - that is, if a particular girl and boy

both used negative concord about as often, the girl would probably use relative what significantly

less often than the boy. The reverse was true for a third construction, ain't (instead of present-tense,

negative auxiliary have or be): among the 'delinquents', it was used more often by girls than by

boys.

If the only concept we have for describing facts such as these is 'dialect', then we have two options:

either we ignore the differences among the three constructions and assign them all to the same

dialect ('delinquent adolescents'), or we recognise the differences and distinguish two different

dialects ('delinquent girls', 'delinquent boys'). In the first case the description fails to show

important distinctions; in the second it misses important similarities (namely, that negative concord

has the same status in both dialects). Worse still, in either case the description entirely lacks the

quantitative dimension. All three of these non-standard constructions were in fact used by all the

teenagers studied, including those who were not classified as 'delinquent', and the groups differed

only in how often they used them.

An alternative to the use of 'dialect' is to include every construction in a single, undivided grammar,

but to link each one directly to any social factors which influence its use. The linkages needed for

the Reading data are shown in (11).

(11)

negative concord ----- delinquents

relative what ----- delinquent boys

ain't --------- delinquentgirls

Although the data from which these linkages are deduced is quantitative, it is debatable whether the

linkages themselves need to be quantitative (Hudson 1986), because the quantitative differences

could derive from aspects of performance such as the degree to which a speaker alligned themself

with the social group concerned.

Two main points arise from this rather simple example. One is that different constructions are

favoured by different social circumstances, which makes the concept 'dialect' much too crude a tool

for showing all the necessary distinctions. The other is that the linkages between constructions and

social circumstances must be part of the speaker's knowledge about the constructions concerned - in

other words, must be part of 'competence'. There is no other way to explain the subtle differences

found between different kinds of speaker - to say nothing of the ability that all speakers have both

to draw conclusions about other speakers' social characteristics on the basis of their use of socially

sensitive constructions, and to 'play' with the social linkages in order to produce different social

impressions.

It is worth mentioning that these general conclusions about constructions are based on a fairly small

number of sociolinguistic research projects, but that a very much larger number of projects in

which the focus was on pronunciation lead to precisely comparable conclusions, with the difference

that the social linkages are with pronunciation features (either general or in particular words).

8 Quantitative Approaches to Syntactic Analysis

The evidence for claims about links between constructions and the social context is mostly

quantitative. A variety of methods are used, but they all derive from the work of William Labov,

who has been the dominant figure in quantitative sociolinguistics since his work in the 1960's on

phonological variation (see the collections in Labov 1972a, 1972b). Two particularly influential

papers dealt specifically with syntactic variation in New York: one (1969) about the use of the zero

copula (characteristic of black speakers), the other (1972c)about negative concord. These papers

are both included in the 1972a collection. Labov's work has inspired a spate of research projects,

some of which included syntactic variation among the linguistic features studied. These works are

reported at the annual 'NWAV' ('New Ways of Analyzing Variation') conferences (e.g. Denning et

al. 1987), but the following is a representative sample of the syntactic studies: Sankoff

(1973),Thelander (1976), SankofflThibault (1977), SankoffNincent (1977), Sankoff/Laberge

(1978), KrochlSmall (1978), SankofflThibault (1978), Klein/Dittmar (1979), Dines (1980), Naro

(1981), Cheshire (1982a, 1982b), Weiner/Labov (1983), Kikai et al. (1987), Lemieux (1987),

Pooley (1988).

These studies all use the same basic methodology (Hudson 1980, 138ft). Assuming that the

researcher has already identified a population of speakers to be studied, then a sample of these

speakers is identified. A reasonable amount of speech by each speaker is recorded (under more or

less carefully controlled conditions), producing a set of texts which can then be compared

quantitatively, with respect to the use of a (pre-selected) set of constructions. For each construction,

the researcher counts the number of times it is used in each text, as a proportion of the number of

times it might have occurred (a notion that we shall discuss below). This gives a figure for each text

which can be compared with figures for other texts, and also with the figures for other

constructions in the same text. During the analysis various distinctions can be made between

different kinds of use for a particular construction - e. g. according to the kind of linguistic context

in which it occurs - and these distinctions can also be reflected in the final text figures. Statistical

comparisons can be made among the various texts to discover significant trends, and on the basis of

these statistics generalisations can be made. These methods clearly contrast with those used in

descriptive linguistics, where the main method is non-quantitative: the elicitation of judgements

from a native informant (who may be the linguist themself). However, a complementary method is

also used in sociolinguistics which is somewhat like this elicitation method, namely judgements on

tape-recorded speech as to the social characteristics of the speaker. This method is sometimes used

as a check on the results of the textanalysis method.

One of the details of the quantitative method as applied to syntax deserves some discussion. The

aim of the method is to compare texts with respect to the frequency of occurrence of some

construction, but this raises the question of what 'frequency' means in this context - what is the unit

X such that the construction occurs, on average, so many times per X? X clearly cannot be a unit of

time (e.g. ten minutes), because the figures are likely to be influenced, in a quite irrelevant way, by

factors such as the speaker's speed of delivery. In the most straightforward cases, it is possible to

give quite a satisfactory answer: X is a fIxed number of occasions on which the intended meaning

was compatible with the construction. In other words, one counts the number of times the

construction occurs, and presents it as a proportion of the times when it could have occurred

without changing the meaning. If meaning is kept constant in this way, then we can probably

assume that the choice between the alternative constructions is motivated by social influences,

so whatever fIgures we find can be used as evidence for a sociolinguistic analysis of the data.

In these straightforward cases, the construction has a meaning which is expressed by one or more

other constructions that are all easily identifIed and mutually substitutable. For example, it would

be quite easy to deal with any of the three constructions found in Reading English mentioned above

(negative concord, relative what and ain't), because in each case it is relatively easy to identify

constructions whose meanings are the same. Thus, a negative-concord sentence like (12a) is an

alternative to a standard one like (12b),

(12)

a. I didn't do nothing.

b. I didn't do anything.

The researcher would therefore find out what proportion of sentences of either type had negative

concord. If this figure had been calculated for each text, then it would be possible to make

meaningful comparisons between the texts. This method of analysis is the one which was

developed for handling variations in pronunciation, and when analysed in this way each

construction is called a variant on some SOCIOLINGUISTIC VARIABLE.

However, it has often been pointed out that there are some constructions where it is hard, or even

impossible, to treat syntactic variation in this way (e.g. Lavandera 1978, Dines 1980, Cheshire

1987). For example, in some cases there is no alternative, synonymous construction because the

variation involves semantic structures as well as syntactic ones - e. g. this may be true of some of

the variation in creole continuums mentioned above (Winford 1984). It also arises in urban dialects

such as Reading - for example, according to Cheshire (1982), Reading teenagers use tag questions

consisting of in (a form of ain't) plus subject in a way that is not parallelled in standard English, to

show aggression after conveying new information. Thus when (13) was uttered the speaker knew

that the addressee did not know that he was going.

(13)

No, I'm going, mate, in I.

Whether the correct account of this tag question should be in grammatical or pragmatic terms, the

fact remains that in standard English, used according to standard pragmatics, no tag would have

been used in these circumstances.

In cases like this the construction under observation has no alternatives other than saying nothing,

so there is no sociolinguistic variable, according to the normal definition of this term. Alternative

methods of quantification have to be found for making texts comparable, all of which are likely to

be somewhat less sensitive, because other variables are not controlled to the same extent. Many

possibilities suggest themselves; for example, Sankoff/Thibault (1978) suggest taking some fixed

number of running words - say, 1,000 words - as the unit in relation to which the occurrences of a

construction are counted. Another possibility worth considering as the basic unit is a fixed number

of words of the class on which the construction concerned depends - e.g.main verbs, in the case of

tag questions. It is an empirical matter which of these alternatives offers the most revealing results,

but it is certainly not necessary to conclude that syntactic variation cannot be studied quantitatively

because some constructions have no alternatives.

9 Quantitative Methods and Grammatical Theory

One of the facts about quantitative studies of syntax of which syntacticians ought to be aware is

that it is possible to relate a construction quantitatively to its purely linguistic environment. Indeed,

many 'sociolinguistic' studies are primarily concerned with precisely such relations, rather than with

social influences, a classic example being Labov's 1969 paper on zero copulas in the speech of

Black Americans. Although this describes and compares the speech of different social groups, a

great deal of the discussion is concerned with the structure of the (transformational) rules

responsible for the construction, and with their relations within the grammar. The level of

argumentation about the pros and cons of the alternative analyses is as high as any in the

transformational literature of the 60's, and the conclusions are such as to interest even the most asocial grammarian. The first sentence of the paper is worth quoting:

"The study of the Black English Vernacular […] provides a strategic research site for the analysis

of English structure in general." (Labov 1969).

One thing that makes this paper (and most others which apply the quantitative method) important

for the practising grammarian is that they provide a new source of evidence on which grammatical

analyses can be built. The evidence consists of quantitative data on language use, showing how

probable some construction is under various circumstances. (Figures for probabilities are different

from those for actual occurrences in particular texts; the former can be derived from the latter,

given a sufficient body of data (Cedergren/Sankoff 1974), and are clearly more relevant to

grammar.) The probability typically varies from one linguistic environment to another; for

example, Labov found a major difference in his study of zero copulas according to whether the

subject was a pronoun or a full NP, illustrated respectively by the sentences in (14), in which the

zero copula is marked by a gap.

(14)

a. He just feel like he _ getting cripple up from arthritis.

b. Boot _ always comin' over my house to eat, to ax for food.

Labov found that all the black speakers in his sample, under all circumstances, were more likely to

use a zero copula after a pronoun than after a full NP, though all of them on occasion used the full

(uncontracted) copula instead, and some speakers were much more likely to use it than others. How

is this fact to be explained? It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the differences in performance

between the two environments must relate to some difference in the grammar, though, as we shall

see in the next section, it is a matter of considerable debate as to precisely what that difference

might be. The alternatives to a grammatical account are an explanation in pragmatic terms, or one

in psycholinguistic terms, but it is hard to see how either of these accounts could predict the

differences concerned. Failing an alternative, then, we must assume that the grammar must

distinguish the two environments in which the zero copula is used (i. e. in which the copula is not

used). This in spite of the fact that, in terms of what is simply possible or impossible, there is no

difference between them - the zero copula is possible, for all relevant (i.e. black) speakers, in both

environments. Quantitative data allow one to investigate the interactions between rules in a way

that is not otherwise possible. In Labov's analysis of zero copulas, this involved considering the

rule for reduced verb-forms (such as s for is). Interestingly he found precisely the same pattern of

environmental influence here too: reduced forms were much more likely after a pronoun subject

than after a full NP. This was equally true for white speakers, who did not use the zero copula at

all. The conclusion Labov drew from this fact was that the zero copula is in fact a sub-case of the

reduced copula, a conclusion which was strongly supported by other data - e. g. the fact that the

zero copula seems to be ruled out in precisely the same environments where overt reduced forms

are excluded, notably when stranded without a following complement. Thus (15a) is impossible,

according to Labov's analysis, for just the same reason as (15b).

(15)

a. *He is as nice as he says he_ .

b. *He is as nice as he says he's.

It could of course be argued that Labov could have arrived at precisely the same conclusions on the

basis of non-quantitative data like (15) alone, but the quantitative data provide independent

confirmation which makes the conclusions that much firmer. Moreover there are some cases where

quantitative data are probably more reliable than judgements, influenced as the latter often are by

prescriptive attitudes. The value of quantitative data in linguistic analysis has been widely

recognised by sociolinguists (e.g. Wolfram 1975).

Quantitative differences between constructions are also relevant to one of the most general issues in

current syntactic theory, the status of 'constructions'. The notion of 'a construction' is admittedly

vague (e.g. is 'agentless passive' a different construction from 'passive'?), but it has played an

important part in most theories of grammar. However it has now become a matter of controversy

because according to Government-Binding theory there are no 'construction-specific' rules - that is,

grammars do not refer to constructions, in the traditional sense. Linguists may refer to constructions

such as 'agentless passives' or 'zero-copula sentences' when they are discussing their analyses, but

such notions play no part in the grammar itself. Instead, the grammar contains rules and principles

which all apply to a variety of constructions; so a construction reflects the intersection of a set of

rules and principles none of which is uniquely responsible for it. This view has been contested by

other grammarians, most clearly by those working in the tradition of Construction Grammar (e.g.

Fillmore et al. 1988).

The relevance of quantitative data to this debate is that constructions have distinctive probabilities

of occurrence, which are unlikely to be derivable from the intersecting probabilities of the rules and

principles responsible for them (though it has to be admitted that this possibility has not in fact

been investigated seriously). We have already seen examples of this - e.g. negativeconcord and

zero-copula constructions. There are different ways in which a probability could be linked to a

construction, but all of them require a direct linkage; one has already been hinted at, namely that

the probability of some construction C could relate more directly to the social categories with

which C is associated. But whatever kind of connection one assumes between constructions and

probabilities, the fact remains that some probabilities seem to be unique properties of particular

constructions. If this is so, then it probably follows that the construction must have independent

status in the grammar, because otherwise there would be nothing to which the probability could

relate.

We have considered two ways in which probabilistic data may be relevant to descriptive and

theoretical grammar:

as an extra source of evidence for the relatedness of constructions;

as evidence for the reality of constructions.

Both of these suggestions raise general questions, notably about the psychological or social status

of grammars, and the serious debate has obviously hardly begun.

10 The Locus of Grammars and of Variation

One of the most general questions that sociolinguistic work raises is about the 'locus' of grammars:

is a grammar a property of an individual, or of a community? Putting the same question in a

different form, is a grammar a model of a psychological or of a social reality? A second question,

which is in fact closely related to the first, is about the locus of variation: what is the linguistic unit

of variation? Is it a variety, or a linguistic item (e.g. a construction)? The evidence from

sociolinguistics throws light on both of these questions. The traditional view on the locus of

grammars is that they are properties of communities - e.g. 'English grammar' is defined in relation

to the community of English speakers. This is a reasonable view if one thinks in terms of standard

languages, supported by prescriptive grammars; and it is not unreasonable when one views

language from the point of view of the language-learner, who aims to identify themself as far as

possible as a member of some community (or set of intersecting communities) by learning its

language perfectly. This view seems to be accepted by Chomsky, when he talks of an ideal speaker

knowing the language of their community perfectly (Chomsky 1965). It is also accepted by Labov,

who argues (1972b, 247) that many of the regularities discovered by sociolinguists are unlikely to

be generally known to members of the community concerned, but they should nevertheless be

included in a grammar - from which it follows that the grammar must be a property of the

community, not of the individual (because it helps to predict the behaviour of the community, and

not that of any given individual). Another major contributor to sociolinguistic theory, Bickerton,

suggests that a community grammar generates the range of possible sub-grammars ('lects') that are

available to individual speakers (Bickerton 1975). In contrast, most theoretically-oriented linguists

these days seem to accept Chomsky's other view of grammar as a part of the individual's mind (a

view which is quite separate from the much more contentious claim that language is a separate

'module' or 'organ' of the mind). The same is also true of many people working within the paradigm

of sociolinguistics. For example,Kay(1978)and Kay/McDaniel (1979) argue that Labov's own

quantitative data show that there are regularities within some communities that could not be shown

within a single grammar (because the influences of particular environments are ordered differently

for different sections of the community). Similar points can be made in relation to the deep,

underlying differences in structure between the alternants found, inter alia, in creole continuums

(e.g. Harris 1984,Winford 1988).

It is hard to be sure, in this dispute, whether there is any more at stake than terminology. It is

beyond dispute that individuals have mental grammars, and that these may vary, at least in minute

details, from person to person even within a small, close-knit community. It is also agreed that

there are regularities in the linguistic differences between speakers in particular communities, and

also regularities between the speech used under socially different circumstances which cut across

differences between individuals. The question at issue seems to be whether it is appropriate to call a

desription of these regularities a 'grammar'. Of course, there is more at stake than this, because

those who believe that a grammar can be used for these purposes also believe that the regularities

are such that they can be described successfully in terms of some grammar such as a

transformational grammar. This is a theoretical matter, and probably one that can be resolved

empirically. However there has been very little discussion in these terms, and there is no real

substance to the debate at present. Let us assume, then, that 'grammar' refers to the knowledge of an

individual speaker (leaving open the possibility of a cross-community description which may or

may not also be called 'grammar'). What relation is there between individual grammars and

variation of the kind described in this article?

It certainly is not the case that by narrowing the scope down to an individual speaker's grammar we

have identified a homogeneous 'idiolect', in which there is no variation - or more precisely, in

which all variation can be described satisfactorily in terms of the notions 'optional' and 'free

variation'. Let us briefly review the phenomena that we have already surveyed which have involved

variation within the speech of one speaker which could not be treated in this way.

Most recently we have seen that even if two constructions are both possible in some linguistic

environment, they may not be equally probable. We assume that such probability differences

need to be explained, and in at least some cases is seems that any explanation must refer to the

specific construction concerned, rather than just to general pragmatic or processing principles.

We have mentioned 'register' differences, which involve variation within the speech of one

person (e.g. between technical and nontechnical, or formal and informal). These differences are

closely related to differences in the social circumstances, and such connections are known to the

speaker - indeed, they could not occur if they were not known.

We have shown how code-mixing can involve the change from one language to another within a

single sentence, and how this process is controlled by constraints on the points at which switches

are permitted constraints which are presumably at least partly learned, since they vary between

communities. We have also mentioned that speakers who code-mix can in fact distinguish their

languages when this is necessary, for instance when speaking to a monolingual, so the codemixing is done on the basis of what speakers know about their languages.

It is agreed by all sociolinguists that speakers can, and do, have an active as well as a passive

command of more than one variety. The multilingual speaker is just a particularly glaring case of

this phenomenon. Where some construction is typically used by some kind of speaker, or under

some kind of circumstances, this fact will be known by many speakers, and will be exploited by

them in understanding speakers of different dialects, in deducing social information about

strangers, and even in trying to pass themselves off as speakers of other varieties.

The most general point that emerges from all of this is that people know a wide range of things

about constructions (as well as about sounds and words). Some of these things are internal to

language - e. g. about the linguistic environments where the construction can occur, or about the

language to which the construction belongs. But some of the known facts concern relations

between the construction and non-linguistic categories, such as the type of person who typically

uses it, or thecircumstances under which it is used. Whether we include these known facts under the

term 'competence' seems to be nothing but a matter of terminology. We can at least call them

'knowledge of language'.

What seems to be needed, if the findings of sociolinguistics are ever to interact with theories of

syntax, is a general theory about knowledge of language which can accommodate all these kinds of

knowledge. (One candidate for such a theory is Word Grammar Hudson 1980, 1984, 1985, 1986,

1987, 1988, 1990.) Alongside this theory we need a model of performance which takes account of

the fact that speakers identify themselves as members of particular social groups, acting under

particular social circumstances. The findings of sociolinguistics will provide a rich source of data

against which the predictions of this model can be tested.

Sociolinguists and specialists in language structure need to collaborate in this enterprise. At present

sociolinguists probably deserve the criticism levelled by Rickford (1988), one of their leading

members, for "a tendency to be satisfied with observation and description, and [for being]

insufficiently imbued with the thirst for theoretical explanation and prediction which drives science

onward." At the same time, most syntacticians pay far too little attention to the findings of

sociolinguists in their theory-building activities.

11. References

Aguirre, Adalberto. 1985.An experimental study of code alternation. International Journal of the

Sociology of Language 53. 59-82.

Bailey, Guy,and Natalie Maynor. 1985.The present tense of be in white folk speech of the Southern

United States. English World Wide 6. 199-216.

Bautisita, Maria L. S. 1980.The Filipino bilingual's competence. A model based on an analysis of

Tagalog-English code-switching. Canberra.

Bell, Allan. 1985. One rule of news English: geographical, social and historical spread. Te Reo 28.

95-117.

Bickerton, Derek. 1973.The nature of a creole continuum. Language 49. 640-669.

-. 1975. Dynamics of a Creole continuum. Cambridge.

Blake, Robert. 1987. Is to/a the head of S? I don't want to decidir la 'cuestion, but I'm going to.

Variation in Language, ed. by Denning et aI., 22-34.

Bokamba, Eyamba. 1987. Are there syntactic constraints on code-mixing? Variation in Language,

ed. by Denning et aI., 35-51.

Cedergren, Henrietta, and David Sankoff 1974. Variable rules: performance as statistical reflection

of competence. Language 50. 333-355.

Cheshire,Jenny. 1982a.Variation in an English Dialect. A sociolinguistic study. London.

- . 1982b.Linguistic variation and social function. Sociolinguistic Variation in Speech

Communities, 153-166. London.

-. 1987. Syntactic variation, the linguistic variable and sociolinguistic theory. Linguistics 25. 257282.

Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge.

Denning, Keith, Sharon lnkelas, Faye McNair-Knox, and John Rickford. 1987. Variation in

Language. NWAV-XVat Stanford.

Dik, Simon C. 1978. Functional Grammar. Amsterdam.

Dines, E. 1980. Variation in discourse - and stuff like that. Language in Society 9. 13-31.

Edwards, Walter. 1985. Intra-style shifting and linguistic variation in Guyanese speech.

Anthropological Linguistics 27. 86-93.

Fasold, Ralph. 1969. Tense and the form be in Black English. Language 45. 763-777.

Ferguson,Charles.1971.Absence of copula and the notion of simplicity: a study of normal speech,

baby talk, foreigner talk and pidgins. Pidginization and Creolization of Languages, ed. by Dell

Hymes, 141-150. London.

Fillmore, Charles, Paul Kay, and Mary L O'Connor. 1988. Regularity and idiomaticity in

grammatical constructions. Language 64. 501-538.

Gumperz, John, and Robert Wilson. 1971. Convergence and creolization. A case from the IndoAryan/Dravidian border in India. Pidginization and Creolization of Languages, ed. by Dell Hymes,

151-167. London.

Halliday, Michael. 1985.An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London.

Harris, John. 1984. Syntactic variation and dialect convergence. Journal of Linguistics 20. 303-327.

-. 1986. Expanding the superstrate: habitual aspect markers in Atlantic Englishes. English World

Wide 7.171-199.

Holm, John. 1988. Pidgins and Creoles I. Theory and structure. London.

Horrocks, Geoffrey. 1987. Generative Grammar. London.

Hudson, Richard. 1980. Sociolinguistics. London.

- . 1984.Word Grammar. Oxford.

-. 1985. A psychologically and socially plausible theory of language structure. Meaning, Form and

Use in Context, ed. by Deborrah Schiffrin, 150-159.Washington, D.C.

- . 1986. Sociolinguistics and the theory of grammar. Linguistics 24. 1053-1078.

-. 1987.Grammar, society and the pronoun. Language Topics. Essays in Honour of Michael

Halliday, ed. by Ross Steele & Terry Treadgold, 493-505. Amsterdam.

- . 1988. Identifying the linguistic foundations for lexcial research and dictionary design.

International Journal of Lexicography 1. 287-312.

-. 1990. English Word Grammar. Oxford.

Kay, Paul. 1978. Variable rules, community grammar and linguistic change. Linguistic Variation:

Models and methods, ed. by David Sankoff, 71-83. London.

-, and Chad McDaniel. 1979.On the logic ofvariable rules. Language in Society 8. 151-187.

Keddad, Sadika. 1986. An analysis of French-Arabic code-switching in Algiers. London

UniversityPhD Dissertation.

Kikai, Akio, Mary Schleppegrell, and Sali Tagliamonte. 1987. The influence of syntactic position

on relativization strategies. Variation in Language, ed. by Denning et aI., 266-277.

Klein, Wolfgang, and Norbert Dittmar. 1979. The Acquisition of German Syntax by Foreign

Workers. Berlin.

Kroch, Anthony, and Cathy Small. 1978. Grammatical ideology and its effect on speech. Linguistic

Variation. Models and methods, ed. by David Sankoff, 45-55. London.

Labov, William. 1969.Contraction, deletion and inherent variability of the English copula.

Language 45. 715-762. [Reprinted in Labov 1972a.]

- . 1972a. Language in the Inner City. Philadelphia.

-. 1972b. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia, Oxford.

-. I972c. Negative attraction and negative concord in English grammar. Language 48. 773-818.

[Reprinted in Labov 1972a.]

Lavandera, Beatrice. 1978. Where does the sociolinguistic variable stop? Language in Society 7.

171-183.

Lederberg,Amy, and Cesareo Morales. 1985.Code switching by bilinguals: evidence against a third

grammar. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 14. 113-136.

Lemieux, Monique. 1987. Clitic placement in the history of French. Variation in Language, ed. by

Denning et aI., 278-299.

Miller, James, and Keith Brown. 1982. Aspects of Scottish English syntax. English World Wide 3.

3-17.

Muthwi, Margaret. 1986.Language use in pluri-lingual societies: the significance of codeswitching. Norwich: University of East Anglia MA Dissertation.

Muysken, Pieter. 1981. Halfway between Quechua and Spanish. The case for relexification.

Historicity and Variation in Creole Studies, ed. by Arnold Highfield & Albert Valdman, 52-78.

Ann Arbor.

Naro, Anthony. 1981. The social and structural dimensions of a syntactic change. Language 57. 6398.

Pfaff, Carol. 1979. Constraints on language mixing: intrasentential code-switching and borrowing

in Spanish/English. Language 55. 291-318.

Pooley, Timothy. 1988. A Sociolinguistic Study of Roubaix (France). London PhD Dissertation.

Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes I'll start a sentence in Spanich Y TERMINO EN ESPANOL:

toward a typology of code-switching. Linguistics 18. 581-618.

Rickford, John. 1988. Connections between sociolinguistics and pidgin-creole studies. International

Journal of the Sociology of Language 71. 51-57.

Romaine, Suzanne. 1980. The relative clause marker in Scots English: Diffusion, complexity and

style as dimensions of syntactic change. Language in Society 9. 221-247.

-. 1984. Relative clauses in child language, pidgins and creoles. Australian Journal of Linguistics 4.

257-281.

Sankoff, David and Suzanne Laberge. 1978.Statistical dependence among successive occurrences

of a variable in discourse. Linguistic Variation. Models and methods, ed. by David Sankoff, 119126. London.

-, and Sylvie Mainville. 1986. Code-switching of context-free grammars. Theoretical Linguistics

13. 75-90.

-, and Pierrette Thibault. 1978.Weak complementarity: tense and aspect in Montreal French. Paper

presented at conference on syntactic change. Michigan.

Sankof/. Gillian. 1973. Above and beyond phonology in variable rules. New Ways of Analyzing

Variation in English, ed. by Charles-James Bailey & Roger Shuy, 44-61. Washington, DC.

-, and PenelopeBrown. 1976.The origins of syntax in discourse. Language 52. 631-666.

- , and Pierrette Thibault. 1977. L'alternance entre les auxiliaires avoir et etre en français parlé à

Montréal. Langue Française 34. 81-108.

-, and David Vincent.1977. L'emploi productif du ne dans le français parlé à Montréal. Le Français

Moderne 45.243-256.

Schmid, Beata. 1986. Constraints on code-switching: evidence from Swedish and English. Nordic

Journal of Linguistics 9. 55-82.

Sciullo, Anne-Marie di, Pieter Muysken, and Rajendra Singh. 1986. Government and codeswitching. Journal of Linguistics 22. 1-24.

Sells, Peter. 1985.Lectures on Contemporary Syntactic Theories. Stanford.

Sobin, Nicholas. 1984.On code-switching inside NP. Applied Psycholinguistics 5. 293-303.

-. 1987. The variable status of Comp-trace phenomena. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 5.

33-60.

Sridhar,S. N., and Kamal Sridhar. 1980. The syntax and psycholinguistics of bilingual codemixing. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 10. 203-215.

Thelander, Mats. 1976. Code-switching or code-mixing. International Journal of the Sociology of

Language 10. 103-123.

Washabaugh, William. 1977. Constraining variation in decreolization. Language 53. 329-352.

Weiner, Judith. and William Labov. 1983. Constraints on the agentless passive. Journal of

Linguistics 19.29-58.

Winford,Donald. 1984. The linguistic variable and syntactic variation in creole continua. Lingua

62.267-288.

-. 1985. The syntax of fi complements in Caribbean English Creole. Language 61. 588-624.

- . 1988.The creole continuum and the notion of the community as locus of language. International

Journal of the Sociology of Language 71. 91-105.

Wolfram, Walt. 1975.Variableconstraints and rule relations. Analyzing variation in language, ed.

by Ralph Fasold & Roger Shuy, 70-88. Washington, DC.

Woolford, Ellen. 1983. Bilingual code-switching and syntactic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 14. 520536.