ABSTRACT - Rutgers University

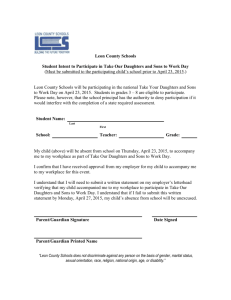

advertisement