CHAPTER OVERVIEW

advertisement

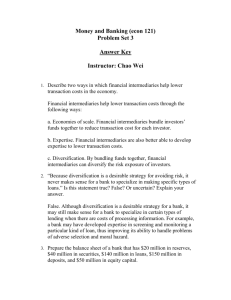

Chapter 32 - Money Creation CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO MONEY CREATION CHAPTER OVERVIEW The central topic of this chapter is the creation of checkable (demand) deposit money by commercial banks. First, a number of routine but significant introductory transactions are covered, followed by an assessment of the lending ability of a single commercial bank. Second, the lending ability and the money multiplier of the commercial banking system are traced through the balance statements of individual banks and through the summary Table 32.2. NOTES I. Learning objectives – In this chapter students will learn: A. Why the U.S. banking system is called a “fractional reserve” system. B. The distinction between a bank’s actual reserves and its required reserves. C. How a bank can create money through granting loans. D. About the multiple expansion of loans and money by the entire banking system. E. What the monetary multiplier is and how to calculate it. II. Introduction: Although we are fascinated by large sums of currency, people use checkable deposits for most transactions. A. Most transaction accounts are “created” as a result of loans from banks or thrifts. B. This chapter demonstrates the money-creating abilities of a single bank or thrift and then looks at that of the system as a whole. C. The term depository institution refers to banks and thrift institutions, but in this chapter the term bank will be often used generically to apply to all depository institutions. III. The Fractional Reserve System: The Goldsmiths A. Banks in the U.S. and most other countries are only required to keep a percentage (fraction) of checkable deposits in cash or with the central bank. B. In the 16th century goldsmiths had safes for gold and precious metals, which they often kept for consumers and merchants. They issued receipts for these deposits. C. Receipts came to be used as money in place of gold because of their convenience, and goldsmiths became aware that much of the stored gold was never redeemed. D. Goldsmiths realized they could “loan” gold by issuing receipts to borrowers, who agreed to pay back gold plus interest. E. Such loans began “fractional reserve banking,” because the actual gold in the vaults became only a fraction of the receipts held by borrowers and owners of gold. F. Significance of fractional reserve banking: 1. Banks can create money by lending more than the original reserves on hand. (Note: Today gold is not used as reserves). 32-1 Chapter 32 - Money Creation 2. Lending policies must be prudent to prevent bank “panics” or “runs” by depositors worried about their funds. Also, the U.S. deposit insurance system prevents panics. IV. A Single Commercial Bank A. A balance sheet states the assets and claims of a bank at some point in time. B. All balance sheets must balance, that is, the value of assets must equal value of claims. 1. The bank owners’ claim is called net worth. 2. Nonowners’ claims are called liabilities. 3. Basic equation: Assets = liabilities + net worth. C. Formation of a commercial bank: Following is an example of the process. 1. In Wahoo, Nebraska, the Wahoo bank is formed with $250,000 worth of owners’ stock shares (see Balance Sheet 1). 2. This bank obtains property and equipment with some of its capital funds (see Balance Sheet 2). 3. The bank begins operations by accepting deposits (see Balance Sheet 3). 4. Bank must keep reserve deposits in its district Federal Reserve Bank (see Table 32.1 for requirements). a. Banks can keep reserves at Fed or in cash in vaults (“vault cash”). b. Banks keep cash on hand to meet depositors’ needs. c. Required reserves are a fraction of deposits, as noted above. D. Other important points: 1. Terminology: Actual reserves minus required reserves are called excess reserves. 2. Control: Required reserves do not exist to protect against “runs,” because banks must keep their required reserves. Required reserves are to give the Federal Reserve control over the amount of lending or deposits that banks can create. In other words, required reserves help the Fed control credit and money creation. Banks cannot loan beyond their excess reserves. 3. Asset and liability: Reserves are an asset to banks but a liability to the Federal Reserve Bank system, since now they are deposit claims by banks at the Fed. E. Continuation of Wahoo Bank’s transactions: 1. Transaction 5: A $50,000 check is drawn against Wahoo Bank by Mr. Bradshaw, who buys farm equipment in Surprise, Nebraska. (Yes, both Wahoo and Surprise exist). 2. The Surprise company deposits the check in Surprise Bank, which gains reserves at the Fed, and Wahoo Bank loses $50,000 reserves at Fed; Mr. Bradshaw’s account goes down, and Surprise implement company’s account increases in Surprise Bank. 3. The results of this transaction are shown in Balance Sheet 5. 32-2 Chapter 32 - Money Creation F. Money-creating transactions of a commercial bank are shown in the next two transactions. 1. Transaction 6: Wahoo Bank grants a loan of $50,000 to Gristly in Wahoo (see Balance Sheet 6a). a. Money ($50,000) has been created in the form of new demand deposit worth $50,000. b. Wahoo Bank has reached its lending limit: It has no more excess reserves as soon as Gristly Meat Packing writes a check for $50,000 to Quickbuck Construction (See Balance Sheet 6b). c. Legally, a bank can lend only to the extent of its excess reserves. 2. Transaction 7: When banks or the Federal Reserve buy government securities from the public, they create money in much the same way as a loan does (see Balance Sheet 7). Wahoo bank buys $50,000 of bonds from a securities dealer. The dealer’s checkable deposits rise by $50,000. This increases the money supply in same way as the bank making the loan to Gristly. 3. Likewise, when banks or the Federal Reserve sell government securities to the public, they decrease supply of money like a loan repayment does. G. Profits, liquidity, and the federal funds market: 1. Profits: Banks are in business to make a profit like other firms. They earn profits primarily from interest on loans and securities they hold. 2. Liquidity: Banks must seek safety by having liquidity to meet cash needs of depositors and to meet check clearing transactions. 3. Federal funds rate: Banks can borrow from one another to meet cash needs in the federal funds market, where banks borrow from each other’s available reserves on an overnight basis. The rate paid is called the federal funds rate. V. The Banking System: Multiple-Deposit Expansion (all banks combined) A. The entire banking system can create an amount of money which is a multiple of the system’s excess reserves, even though each bank in the system can only lend dollar for dollar with its excess reserves. B. Three simplifying assumptions: 1. Required reserve ratio assumed to be 20 percent. (The actual reserve ratio averages 10 percent of checkable deposits.) 2. Initially banks have no excess reserves; they are “loaned up.” 3. When banks have excess reserves, they loan it all to one borrower, who writes check for entire amount to give to someone else, who deposits it at another bank. The check clears against original lender. C. System’s lending potential: Suppose a junkyard owner finds a $100 bill and deposits it in Bank A. The system’s lending begins with Bank A having $80 in excess reserves, lending this amount, and having the borrower write an $80 check which is deposited in Bank B. See further lending effects on Bank C. The possible further transactions are summarized in Table 13.2. D. Monetary multiplier is illustrated in Table 32.2. 1. Formula for monetary or checkable deposit multiplier is: 32-3 Chapter 32 - Money Creation Monetary multiplier = 1/required reserve ratio or m = 1/R or 1/.20 in our example. 2. Maximum deposit expansion possible is equal to: excess reserves monetary multiplier, or D M e. 3. Figure 32.1 illustrates this process. 4. Higher reserve ratios generate lower money multipliers. a. Changing the money multiplier changes the money creation potential. b. Changing the reserve ratio changes the money multiplier but be careful! It also changes the amount of excess reserves that are acted on by the multiplier. Cutting the reserve ratio in half will more than double the deposit creation potential of the system. E. The process is reversible. increases that destruction. VI. Loan repayment destroys money, and the money multiplier LAST WORD: The Bank Panics of 1930-1933 A. Bank panics in 1930-33 led to a multiple contraction of the money supply, which worsened Depression. B. Many of failed banks were healthy, but they suffered when worried depositors panicked and withdrew funds all at once. More than 9000 banks failed in three years. C. As people withdrew funds, this reduced banks’ reserves and, in turn, their lending power fell significantly. D. Contraction of excess reserves leads to multiple contraction in the money supply, or the reverse of situation in Table 32.2. Money supply was reduced by 25 percent in those years. E. President Roosevelt declared a “bank holiday,” closing banks temporarily while Congress started the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which ended bank panics on insured accounts. 32-4 Chapter 32 - Money Creation ANSWERS TO END-OF-CHAPTER QUESTIONS 32-1 Why must a balance sheet always balance? commercial bank’s balance sheet? What are the major assets and claims on a A balance sheet is a statement of assets and claims (or liabilities and net worth). It must balance because every asset is claimed by someone, so that assets (the left-hand side) = liabilities + net worth (the right-hand side). The major assets of a bank are: cash (including cash reserves held by the Fed), its property, the loans it has made, and the securities it holds over and above general loans. Its liabilities are the deposits of its customers. The difference between the assets and liabilities is the bank’s net worth, which is shown on the liabilities side, thus ensuring that the balance sheet balances. 32-2 (Key Question) Why does the Federal Reserve require commercial banks to have reserves? Explain why reserves are an asset to commercial banks but a liability to the Federal Reserve Banks. What are excess reserves? How do you calculate the amount of excess reserves held by a bank? What is the significance of excess reserves? Reserves provide the Fed a means of controlling the money supply. It is through increasing and decreasing excess reserves that the Fed is able to achieve a money supply of the size it thinks best for the economy. Reserves are assets of commercial banks because these funds are cash belonging to them; they are a claim the commercial banks have against the Federal Reserve Bank. Reserves deposited at the Fed are a liability to the Fed because they are funds it owes; they are claims that commercial banks have against it. Excess reserves are the amount by which actual reserves exceed required reserves: Excess reserves: Excess reserves = actual reserves - required reserves. Commercial banks can safely lend excess reserves, thereby increasing the money supply. 32-3 “Whenever currency is deposited into a commercial bank, cash goes out of circulation and, as a result, the supply of money is reduced.” Do you agree? Explain why or why not. Students should not agree. The M1 money supply consists of currency outside of the banks (cash in the hands of the public) and checking account deposits of the public in the commercial banks. The deposit of currency into a checking account in a bank has changed the form of the money supply but not the amount. 32-4 (Key Question) “When a commercial bank makes loans, it creates money; when loans are repaid, money is destroyed.” Explain. Banks add to checking account balances when they make loans; these checkable deposits are part of the money supply. People pay off loans by writing checks; checkable deposits fall, meaning the money supply drops. Money is “destroyed.” 32-5 Chapter 32 - Money Creation 32-5 Explain why a single commercial bank can safely lend only an amount equal to its excess reserves but the commercial banking system can lend by a multiple of its excess reserves. What is the monetary multiplier, and how does it relate to the reserve ratio? When a bank grants a loan, it can expect that the borrower will not leave the proceeds of the loan sitting idle in his or her account. Most people borrow to spend. Therefore the lending bank can expect that checks will be written against the loan and that the bank will shortly lose reserves to other banks, as the checks are presented for payment, to the full extent of the loan. In short, when a bank grants loans to the full extent of its excess reserves, it can shortly expect to lose these excess reserves to other banks. From this it can be seen why a bank cannot safely lend more than its excess reserves. If it did, it would soon find that its cash reserves were below its legal reserve requirement. From the above it can be seen why the commercial banking system can safely lend a multiple of its excess reserves. Whereas one bank loses reserves to other banks, the system does not. With a legal cash reserve requirement of, say, 20 percent, Bank “B” on receiving as a new deposit the $100 loaned by Bank “A” (the excess reserves of Bank “A”), may safely lend $80 (80 percent of $100). Bank “C”, on receiving as a new deposit the $80 loan of Bank “B”, loans 80 percent of that, namely $64. Note that the $100 initial excess reserves of the banking system have already resulted in the money supply increasing by $244 (= $100 + $80 + $64). The money supply will continue to increase, at a diminishing rate (Bank “D” will increase the money supply by $51.20 in loaning this amount), until the total increase in the money supply is $500. The algebra underlying the monetary multiplier is that of an infinite geometric progression. Designating the fixed fraction of the previous number as b (0.8 in our case) and k as the sum of the progression, we have: k 1 b b2 b3 ...... bn Solving this for a very large n, we get, k 1 / 1 b In our example, the multiplier k is 1/(1 - 0.8) = 1/.2 = 5. And 5 is the reciprocal of the reserve ratio of 20 percent of 0.2. The multiplier is inversely related to the reserve ratio. 32-6 Assume that Jones deposits $500 in currency into her checkable deposit account in First National Bank. A half-hour later Smith obtains a loan for $750 at this bank. By how much and in what direction has the money supply changed? Explain. The loan of $750 to Smith increases the money supply by $750, and that is the only change. The deposit of $500 by Jones does not change the money supply. Whether Jones’ $500 is in her purse or in her demand deposit, the $500 is still part of the money supply. 32-7 Suppose the National Bank of Commerce has excess reserves of $8,000 and outstanding checkable deposits of $150,000. If the reserve ratio is 20 percent, what is the size of the bank’s actual reserves? Required reserves = 20 percent of $150,000 = $30,000 Therefore, required reserves = $30,000; Excess reserves = $ 8,000; Actual reserves = $38,000. 32-6 Chapter 32 - Money Creation 32-8 (Key Question) Suppose that Continental Bank has the simplified balance sheet shown below and that the reserve ratio is 20 percent: Liabilities and net worth (1) (2) Assets (1) (2) Reserves Securities Loans $22,000 38,000 40,000 Checkable deposits $100,000 _____ _____ a. What is the maximum amount of new loans that this bank can make? Show in column 1 how the bank’s balance sheet will appear after the bank has lent this additional amount. b. By how much has the supply of money changed? Explain. c. How will the bank’s balance sheet appear after checks drawn for the entire amount of the new loans have been cleared against this bank? Show this new balance sheet in column 2. d. Answer questions a, b, and c on the assumption that the reserve ratio is 15 percent. (a) $2,000. Column 1 of Assets (top to bottom): $22,000; $38,000; $42,000. Column 1 of Liabilities: $102,000. (b) $2,000. The bank has lent out its excess reserves, creating $2,000 of new demand-deposit money. (c) Column 2 of Assets (top to bottom): $20,000; $38,000; $42,000. Column 2 of Liabilities; $100,000. (d) (a) $7,000. Column 1 of Assets (top to bottom): $22,000; $38,000; $47,000. Column 1 of Liabilities: $107,000. (b) $7,000 (c) Column 2 of Assets (top to bottom): Liabilities: $100,000. 32-9 $15,000; $38,000; $47,000. Column 1 of The Third National Bank has reserves of $20,000 and checkable deposits of $100,000. The reserve ratio is 20 percent. Households deposit $5,000 in currency into the bank that is added to reserves. What level of excess reserves does the bank now have? Checkable deposits have risen to $105,000. Twenty percent of this is $21,000, which are its required reserves. The bank’s actual reserves have risen to $25,000. Therefore, its excess reserves are $4,000 ($25,000 - $21,000). 32-7 Chapter 32 - Money Creation 32-10 Suppose again that the Third National Bank has reserves of $20,000 and demand deposits of $100,000. The reserve ratio is 20 percent. The bank now sells $5,000 in securities to the Federal Reserve Bank in its district, receiving a $5,000 increase in reserves in return. What level of excess reserves does the bank now have? Why does your answer differ (yes, it does!) from the answer to question 9? The bank now has excess reserves of $5,000 (rather than $4,000) because in this case the demand deposits on the liabilities side of its balance sheet did not change. In the former case, $1,000 of new cash reserves was needed against the $5,000 increase in demand deposits. In the present case, nothing occurred on the liabilities side of the balance sheet. The sale of the securities to the Fed caused changes on the assets side only—one asset (securities) was exchanged for another (reserves). 32-11 Suppose a bank discovers its reserves will temporarily fall slightly short of those legally required. How might it remedy this situation through the Federal funds market? Now assume the bank finds that its reserves will be substantially and permanently deficient. What remedy is available to this bank? (Hint: Recall your answer to question 4.) Banks can borrow temporarily from other banks that have temporary excess reserves. These funds are transferred from one bank’s reserve account to the other and allow the lending bank to earn interest on otherwise idle excess reserve funds for an overnight period, while replenishing the reserves of the deficient bank. If a bank finds that its reserves are substantially deficient, it should suspend lending and gradually build up its reserves as borrowers repay loans made by the bank earlier. 32-12 Suppose that Bob withdraws $100 of cash from his checking account at Security Bank and uses it to buy a camera from Joe, who deposits the $100 in his checking account in Serenity Bank. Assuming a reserve ratio of 10 percent and no initial excess reserves, determine the extent to which (a) Security Bank finds it has excess reserves, and (c) loans, checkable deposits, and the money supply change as a result of the transactions. (a) Security Bank will have to reduce its loans and demand deposits by $90, the amount of its new deficiency of reserves. (b) Serenity Bank can safely increase its loans and demand deposits by $90, the amount of its new excess reserves. (c) The entire banking system cannot increase the amount of loans or checkable deposits; the increased excess reserves at Serenity Bank are offset by reduced excess reserves at Security Bank. The money supply has not changed. Bob’s checking account has decreased by $100 and Joe’s checking account has increased by $100. There has been no change in the overall excess reserves in the banking system. 32-8 Chapter 32 - Money Creation 32-13 (Key Question) Suppose the simplified consolidated balance sheet shown below is for the entire commercial banking system. All figures are in billions. The reserve ratio is 25 percent. Assets Liabilities and Net Worth (1) Reserves Securities Loans $ 52 ___ 48 ___ 100 ___ (2) Checkable deposits $200 ___ a. What amount of excess reserves does the commercial banking system have? What is the maximum amount the banking system might lend? Show in column 1 how the consolidated balance sheet would look after this amount has been lent. What is the monetary multiplier? b. Answer the questions in part a assuming that the reserve ratio is 20 percent. Explain the resulting difference in the lending ability of the commercial banking system. (a) Required reserves = $50 billion (= 25% of $200 billion); so excess reserves = $2 billion (= $52 billion - $50 billion). Maximum amount banking system can lend = $8 billion (= 1/.25 $2 billion). Column (1) of Assets data (top to bottom): $52 billion; $48 billion; $108 billion. Column (1) of Liabilities data: $208 billion. Monetary multiplier = 4 (= 1/.25). (b) Required reserves = $40 billion (= 20% of $200 billion); so excess reserves = $12 billion (= $52 billion - $40 billion). Maximum amount banking system can lend = $60 billion (= 1/.20 $12 billion). Column (1) data for assets after loans (top to bottom); $52 billion; $48 billion; $160 billion. Column (1) data for liabilities after loans: $260 billion. Monetary multiplier = 5 (= 1/.20). The decrease in the reserve ratio increases the banking system’s excess reserves from $2 billion to $12 billion and increases the size of the monetary multiplier from 4 to 5. Lending capacity becomes 5 $12 = $60 billion. 32-9 Chapter 32 - Money Creation 32-14 (Last Word) Explain how the bank panics of 1930 to 1933 produced a decline in the nation’s money supply. Why are such panics highly unlikely today? Because we have a fractional reserve banking system, bank reserves support a multiple amount of demand deposit money. When depositors collectively withdraw funds and “cash out” their accounts, bank reserves fall. Although demand deposits fall by the amount of cash withdrawn, the remaining demand deposits are too high relative to the reduced reserves. Banks therefore must call in loans or sell securities to get reserves. Both actions reduce the money supply. Such panics are unlikely today because deposits are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which covers the Bank Insurance Fund (BIF) for bank deposits up to $100,000 for each depositor, and also the Savings Association Insurance Fund (SAIF), which covers deposits up to $100,000 in savings and loan associations. Because Congress stands behind these insurance funds, depositors are not worried about the loss of their funds and, therefore, will not rush to withdraw them whenever they might be slightly worried about a particular institution’s financial health. 32-10