Extensive Reading with Guidance

advertisement

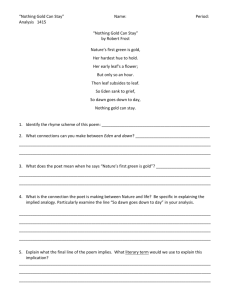

IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo Extensive Reading with Guidance Chin-chuan Cheng1, Chu-ren Huang2, Feng-ju Lo3, Xiang-yu Chen4, Joyce Ya-chi Han5, Yu-chun Huang6 1 Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan chengcc@gate.sinica.edu.tw 2 Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan churen@gate.sinica.edu.tw 3 Yuan-Ze University, Neili, Taiwan gefjulo@saturn.yzu.edu.tw 4 Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan XiangyuC@gate.sinica.edu.tw 5 Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan joycehan@gate.sinica.edu.tw 6 Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan cheryl0712@yahoo.com Abstract A language learning mode called “word-focused extensive reading” has been proposed to facilitate word-usage learning. The user inputs a word in the computer program designed and implemented for reading to find its usage in the context of a sentence. The computer program then searches for the knowledge base for the word and provides guidance to show a summary of the salient features of word collocation. Sentences with the word in question are displayed one at a time. For each sentence the relevant collocating words are highlighted. In this way the reader sees the word collocation so as to recognize the salient features of the word and thus incrementally acquires the knowledge of word usage. The program works with large Chinese and English collections of texts. For Chinese the knowledge of word collocation was built on the basis of the Balanced Corpus of Academia Sinica. The English collocation features were collected from the British National Corpus. The program can also be useful for learning to differentiate near-synonyms. Keywords: computer-assisted language learning, extensive reading, vocabulary learning, usage guidance, Chinese, English 1 Reading for Fluency Words occur with other words in text in certain ways. One needs to learn word collocation of a language to use the language fluently. Native speakers of a language had a dozen formative years to learn to speak the native tongue well through a great deal of linguistic interactions and reading. Adult learners, however, have only a few years to acquire a non-native language. They do not have time to read hundreds of books to gain fluency. Yet extensive reading is required to gain better knowledge of word usage. For example, knowing the meaning of ‘dawn’ as “early morning” or “the period in the day when light from the sun begins to appear in the sky” (Procter 1995) does not lead to the understanding of the correct usage of ‘at dawn’ and the incorrect collocation of ‘in the dawn’. Cheng (1998a, 1998b, 1998c, 2004) has proposed a mode of learning called “word-focused extensive reading” to facilitate learning of word usage. A couple versions of a computer program have been implemented to display sentences with the word the user is studying. The user inputs a word, and the computer program displays the sentences -1- IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo in which the word in question occurs, one sentence at a time. The user can then read each sentence and examine the collocating words. By reading the sentences with the word in hundreds of books or articles, the user should gain an understanding of how the word is used along with other words. The user focuses on one word at a time to read many sentences from the collection of a large amount of texts. That is why the mode is called “word-focused extensive reading”. In this way the user does not have to struggle to read hundreds of books to understand all the words in a short period of time. A particular word is searched and the sentences are read when one has questions about the usage. The word-focused mode of learning will then allow the user to learn to use a word well in a matter of a few minutes instead of a few years otherwise. For example, when the sentences show a large number of the occurrences of ‘at dawn’, the user will naturally use that phrase instead of the incorrect phrase ‘in the dawn’. The sentences so displayed come from a large collection of texts. The software package mentioned in Cheng (1998a, 1998b, 1998c) holds over 200 great English books of the past two hundred years. The current CCWUsage package described in Cheng (2004) uses the British National Corpus of one-billion English words (http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk) and the Balanced Corpus of Academia Sinica with five million Chinese words (http://www.sinica.edu.tw/SinicaCorpus/). The current software allows the user to search word usage in Chinese and in English. There are also some differences between the versions. The earlier version displays sentences only. The current version has explicit guidance to help the user understand collocation features. 2 Determining Collocation Features of Chinese Words As mentioned above, ‘dawn’ occurs with ‘at’ to form the sequence ‘at dawn’. But ‘morning’ referring to the time of the day overlapping with ‘dawn’ occurs with a different preposition to form the phrase ‘in the morning’. It is hoped that during reading of the sentences involving the word in question, the user will automatically understand the usage. However, if the user is not aware of the different collocations between these two words, then reading a lot of sentences in which the words occur will not help. It is therefore useful for the usage program to provide some guidance on word collocation. Sentences of every language exist in a discourse. But some languages require learning of more local matters. For example English prepositions deserve much attention as shown above involving ‘dawn’ and ‘morning’. On the other hand, Chinese word usage can be understood better in a greater context. For example, the Chinese word ‘溺愛’ (to love one’s children excessively) occurs in the context of parents spoiling their children. The following example has been parsed to show the words: 在 父母 方面 , 他們 對於 子女 應該 做到 不 溺愛 及 不 放縱 ; 在 教育 方面 , 有關 單位 需要 加強 生活 輔導 , 實行 常態 分班 , 並且 多多 關愛 學生 ; The word ‘溺愛’ can be used in that context only. Even when parents and children are not mentioned explicitly in the text, it still means parents or family elders spoiling their children: 但是 這 個 世界 上 , 許許多多 的 事情 , 說來 容易 做 來 難 , 鼓勵 的 分寸 , 應該 怎麼樣 來 拿捏 才 不會 變成 溺愛 呢 ? The English explanation of the word as ‘be excessively fond of’ given in Wu et al. (1993) is less precise than ‘spoil (a child); dote on (a child)’ as given in Beijing Foreign Languages University (1995). It is entirely infelicitous or inappropriate to use ‘溺愛’ to describe a student’s love for his or her teacher. This knowledge can be acquired from extensive reading. In preparing for the guidance to be incorporated in the usage software CCWUsage, we had to collect the words collocating with ‘溺愛’ from the Balanced Corpus. The Balanced Corpus has each word tagged with a syntactic category. We found that ‘溺愛’ occurred once as a noun (NV) and eight times as a transitive verb (VC). Since a transitive verb requires an agent and a patient, we extracted the nouns occurring before ‘溺愛’ and those occurring after it. We looked at the collocating words in an entire sentence. The nouns occurring before ‘溺愛’ were the following, with the number of occurrences of the word shown as duplicates in the list: 父母 父母 父母 媽媽 孩子 孩子 小孩子 子女 工商業 人 分寸 方面 世界 他們 -2- IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo 生活 她 我們 事情 傷害 The nouns occurring after ‘溺愛’ were the following: 孩子 孩子 孩子 小孩子 小孩 是非 人 人格 父母 司法 生活 行為 我們 事情 性情 青少年 根本 能力 常態 教育 輔導 價值 學生 學校 物質 者 家庭 小孩子 心理 我 陌生人 規範 學校 小孩子 方面 我們 容忍力 單位 機關 小孩 方面 我們 挫折 腦筋 幫助 We then read the sentences in which ‘溺愛’ occurred and found the following animate agent and patient word types: 父母 媽媽 孩子 小孩子 子女 小孩 At this juncture it was useful to compare the collocation characteristics of near-synonyms such as ‘寵愛’, ‘愛戴’, ‘敬愛’, ‘鍾愛’, etc. The agents and patients of these words are not limited to familial members. We thus made the conclusion that the word ‘溺愛’ is used to describe the action of excessive love of children by parents. We also know from our own language use that grandparents and other family elders can ‘溺愛’ the children in the family. Thus we prepared the following sense as part of the guidance for using the word: 家庭長輩對小輩的過度愛護 Then from the corpus we collected the more significant word collocations and formed the phrases to show the user when the word is requested in the usage program: 父母溺愛子女,父母溺愛小孩子,大人溺愛孩子,過度溺愛,過度地溺愛小孩子,漫無 章法的溺愛 Furthermore we collected the frequency of ‘溺愛’ and noted its one occurrence as a noun and its frequency of 8 as a verb. Thus the following is the guidance to be displayed when the user requests to read about the word ‘溺愛’: 溺愛 (名詞頻:1,動詞頻:8),(家庭長輩對小輩的過度愛護),父母溺愛子女,父母溺 愛小孩子,大人溺愛孩子,過度溺愛,過度地溺愛小孩子,漫無章法的溺愛 That was how we built the usage knowledge for that particular word. We should admit that the word ‘溺愛’ is a simple case. But the illustration of how we built the usage knowledge is clear. Many words have numerous collocating words in the corpus. For example, the word ‘鼓勵’ occurred more than 800 times in the Balanced Corpus, and its collocating words were numerous and varied. Yet by comparing it with a near-synonym ‘慫恿’ and by sifting through the words and their syntactic structures we were able to collect the textual evidence to show its salient usage features. We plan to build a guidance entry for each of the couple thousand high frequency words from the Balanced Corpus. 3 Collecting Collocation Features of English Words Our reading guidance program used the tagged British National Corpus of a billion words to collect collocation features of English words. Our work mainly dealt with short-distance collocating words in a sentence. We examined three words to the left and three words to the right of the concerned word. Chinese learners of English often have difficulty using short words such as prepositions around a substantive word. For example, ‘in the morning’ is a correct expression. But can one say ‘in the dawn’? The frequency of ‘dawn’ is 1,234 in the portion of the British National Corpus that we examined. The collocating words and their frequency in parentheses in the three positions to the left and to the right are given in Table 1. The table only shows the words with a frequency higher than 19 except that ‘came’ and ‘broke’ with lower frequency were added to show the use of the verbs. Noun-verb collocation characteristics are important matters of diction. ‘Dawn’ can break. ‘Evening’ cannot. That is why we listed ‘broke’ in the table. -3- IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo Table 1 ‘dawn’ and its collocating words. 3 the (85) of (27) 2 a (84) the (60) 1 the (255) at (218) and (26) just (44) in (25) was (23) to (22) a (20) Word dawn 1,234 1 of (119) and (72) 2 the (93) dusk (42) Before (70) a (38) crack (30) of (29) before (116) of (91) after (40) on (48) to (47) and (30) in (25) light (21) up (20) and (20) at (20) a (39) from (27) by (25) as (22) until (20) was (25) the (21) to (21) 3 the (92) a (24) <VBD>was (25) <VVD>came (15) <VVD>broke (14) One can see in the table that ‘at’ precedes ‘dawn’ with a high frequency. The word ‘morning’ on the other hand forms ‘in the morning’ as can be seen in Table 2. Table 2. ‘morning and its collocating words. 3 a (665) 2 in (3476) 1 the (5105) the (558) on (500) the (1720) on (938) this (3823) next (1134) o'clock (405) in (264) and (257) up (252) of (564) that (656) Word morning (18,218) as a noun I (351) early (476) Sunday (453) Saturday (407) every (401) good (400) tomorrow (369) following (365) Monday (352) yesterday (326) -4- 1 and (1132) 2 the (913) of (422) I (334) and (536) a (316) 3 the (622) and (293) <VBD>was (279) <VVD>came <VBD>was a (262) (27) (255) IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo In Table 1 one finds the word ‘in’ in the second position to the left and ‘the’ in the first position to the left. The listing might give the impression that ‘in the dawn’ occurs frequently. In fact as we read the sentences in the corpus we found the combinations such as ‘in a dawn raid’ and usually not ‘in the dawn’. In an earlier version of the reading guidance we showed the tables to the user as summaries of the features of ‘dawn’ and ‘morning’ (Cheng 2004). Now we feel that a gentler guidance on the usage should not require the user to decode the complex information given in crowded tables.. Thus the initial display of the collocation features for these two words now looks like the following: Dawn (frequency 1,234) at dawn, until dawn, after dawn, dawn on, from dawn till nightfall, from dawn to dusk, dawn breaks, dawn comes Morning (frequency 18,218) in the morning, good morning, misty morning, until morning, early morning, mid-morning, the morning after, next morning The frequency information will eventually be changed to show frequency bands rather than absolute counts of occurrences of the words. It is a long process to build the usage information. But not all the user of the usage program will automatically gain the knowledge of word usage. It is therefore a useful guidance to many who learn English as a second language. 4 Reading with Guidance The usage program for extensive reading has the commands and functions as given in Figure 1. Of concern now are the functions of usage for Chinese and for English. Figure 1. Usage program commands and functions. The language choices are Chinese and English. When Chinese is selected, the user is asked to choose a folder of texts for search. We use the parsed texts from the Balanced Corpus. But other users can select any texts, even without word segmentation. The program then allows the user to input a word to search the sentences where it occurs. Sentences are displayed one at a time. Initially the guidance provides some collocation information as shown in Figure 2 for the Chinese word ‘溺愛’. Figure 2. Reading with guidance for ‘溺愛’. -5- IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo The user can click the button “Continue” to read the next sentence with the word in it. The word in question is highlighted in red color. Similarly when the word ‘鼓勵’ is entered to be searched, the program initially shows the following guidance: 鼓勵 (名詞頻:163,動詞頻:733),(促使他人做正面的事,雙方關係為上對下),鼓勵 學生,鼓勵青年,鼓勵企業,鼓勵我們增加信心,鼓勵勞動致富,鼓勵孩子們的上進心, 互相鼓勵 The English reading guidance works in the same way as Chinese except that local collocation words are extracted and displayed as an entry after the display of each sentence. As we mentioned earlier, major usage problems that Chinese speakers encounter are often the words surrounding substantive words. That is why the usage guidance highlights the local collocating words. Figure 3. Reading with guidance for ‘dawn’. Here ‘at dawn’ is extracted from the sentence and further displayed below it. As the user continues to read, the high frequent of ‘at dawn’ will become part of the usage knowledge. In an earlier version of the program the frequency of occurrence was tabulated and the number was shown during the reading process to emphasize the quantitative information. In the current version, that functionality becomes an option. 5 Searching for Phrases The usage program is not for simplex words only. The user can also input phrases to examine their usage. For example, one can say ‘睡覺’ and ‘睡了覺’. But can ‘體操’ be separated as ‘體了操’? The usage program found sentences using ‘睡了覺’ , for example: 讓 我 舒舒服服 地 睡 了 一 大 覺 。 她 睡 了 一 個 午覺 , 我們 都 痛快 地 睡 了 一 個 懶 覺 , However, no sentences with ‘體了操’ could be found in the large corpus. Therefore learners of Chinese can use the program as a guide to decide what to use and what not to use. Linguists can use it to examine Chinese syntactic patterns. Similarly, phrasal search can yield useful information on usage and word sense in English. Following are examples of segments of sentences with the phrase ‘in his mind’. … a thought beginning to burgeon in his mind. All too often the pilot has a plan in his mind and sticks to it … -6- IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo Some phrases lay in his mind for years. A year later, they were still in his mind when thinking simply of western civilization; Here one can see that ‘in his mind’ means he is thinking about something. On the other hand, the following lines show that ‘on his mind’ means that he is worried about something: He's got a lot on his mind right now, not least how Renault's going to cope with a future hand-in-hand relationship with Volvo. Michael had a problem on his mind. He bustled in one day, rubbing his hands, a fashion of his when he had something unpleasant on his mind. If not, why were they so much on his mind? Mungo had so much on his mind that he was unable to concentrate on Mary Ann's stories. The collocation information for Chinese words involves the context of the entire sentence. On the other hand, the guidance for English words deals more with local features. Kilgarriff and Tugwell (2001) have a more ambitious project of automatically constructing sentence structures to show the collocating words as the subject, object, preposition, modifier, etc. Their supposed users are dictionary compilers. These experts can further judge the appropriateness of the analysis and can tolerate mistakes made by automatic processing. Our users are language learners. Errors should not be introduced in the program. We thus take a modest approach of showing only the collocation features without indicating grammatical functions. 6 Conclusions We look up words in dictionaries for their senses. Besides parts of speech and a few notes about grammar, dictionaries usually do not give enough examples to show how the words are used. Without usage examples it is often difficulty to understand how a word is connected with others to make fuller expressions. It is even harder to get fine distinctions of near-synonyms. The usage program that we implemented gives guidance on the salient features of senses, collocation characteristics, and the possibility of viewing a large number of sentences using the word in question. The user of the program can search individual words or combinations of them. If they are not found, then the user will avoid using them. If they are found, then a large number of examples will allow the user to get used to the collocations and consequently to gain fluency in the language. The acquisition of lexical knowledge and the achievement of automatic language use require familiarity of the senses and usage of words. The usage program is designed to allow the user to reach language fluency by studying the use of individual words in many writings. Acknowledgements This work was support by the National Science Council grant NSC93-2524-S-001-003 “Center of E-Resources for Chinese Language Teaching and Learning”. References Beijing Foreign Languages University. 1995. A Chinese-English Dictionary (Revised Edition). Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. Cheng, C.C. 1998a. 一詞泛讀:英文詞語用法檢索軟體 (Focused reading: English word usage retrieval program. In 戴維揚ed. 超倍速英語學習年代 , S1-S11. Taipei: Crane Publishing Co. Cheng, C.C. 1998b. 針對一詞廣泛閱讀:電腦輔助的詞語學習 (Extensive reading for individual words: computer-assisted word learning). 華文世界 (The World of Chinese Language), 87, 30-44. Cheng, C.C. 1998c. 英語用法寶典(English Word Usage). Taipei: Crane Publishing Co. -7- IWLeL 2004, December 10th, 2004, Waseda University, Tokyo Cheng, C.C. 2004. Word-focused extensive reading with guidance. Selected Papers from the 13th International Symposium and Book Fair on English Teaching, 24-32. Taipei: Crane Publishing Co. Kilgarriff, A. and D. Tugwell. 2001. Proceedings of Collocations Workshop 32-38. ACL 2001, Toulouse, France. Procter, P. 1995. Cambridge International Dictionary of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wu, J., P. Mei, and X.P. Ren. 1993. Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary 8th Impression. Hong Kong: Commercial Press and Oxford University Press. -8-