New Public Management Reforms in Denmark and Sweden

Market-type Reforms of the Danish and Swedish Service

Welfare States:

Different Party Strategies and Different Outcomes

Christoffer Green-Pedersen

Assistant Professor

Department of Political Science

University of Aarhus

Bartholins Allé

8000 Aarhus C

Denmark

Phone +4589421133

Fax + 4586139839

Email cgp@ps.au.dk

First draft: Comments most welcome

1

Acknowledgement

I wish to thank Paula Blomqvist, Anders Håkansson, and Anders Lindbom for their help in finding material about the developments in Sweden and the library staff at the Department of Political Science, University of Aarhus for excellent assistance.

2

Abstract

During the last two decades, New Public Management reforms have been discussed in all OECD-countries and in many case also implemented.

Increasingly, scholarly interest has come to focus on the question of why countries implement NPM ideas to a different extent. This paper investigates market-type reforms of the service welfare states in Sweden and Denmark.

Sweden has implemented such reforms to a greater extent than Denmark, and the paper argues that the explanation should be found in the different strategies of the social democratic parties in the two countries In Denmark, the Social Democrats have opposed market-type reforms, whereas in

Sweden, they have been much more open towards these ideas. With its focus on the strategies of the social democratic parties, the paper differs from most other writings about variation in the extent NPM reforms, which focus on institutional factors or different administrative traditions.

3

Introduction

Within the last 20 years, the rich OECD countries have been adjusting their models of welfare capitalism to a changed economic environment (cf. Scharpf and Scmidt 2000). One type of adjustments has been reforms of the public sector generally known as “New Public Management” (NPM). The exact reforms covered by this heading are, for instance, the introduction of explicit measures of performance, decentralization, introduction of private-sector styles of management, contracting out, privatization, and focus on service and client orientation (Hood 1991, Rhodes 1999 and Clark 2000).

The scholarly debate about NPM reforms has increasingly been influenced by what Premfors (

1998) labels the “structured pluralism story” focusing on variation in the extent to which different countries have implemented NPM reforms (e.g. Clark 2000, Peters 1997, Farnham et al.

1996, Flynn & Strehl 1996, Kickert 1997, Pollitt & Summa 1997, Pollitt &

Bouckaert 2000, and Hood 1996). This paper focuses on the question of which factors cause countries to implement NPM reforms to a different extent.

The theoretical claim of the paper is that party politics and especially the strategy of the Social Democrats should receive more attention than is usually the case in the literature on NPM reforms.

The empirical part of this paper is an examination of the extent of market-type reforms of four welfare service areas in Denmark and Sweden, namely health care, elderly care, childcare and primary schools. The paper argues that the extent of such reforms has been greater in Sweden than in

Denmark. The paper then shows how the difference is related to the different strategies of the social democratic parties in the two countries. The Social

Democrats in Sweden (SAP) accepted the NPM agenda including markettype reforms of welfare services at a much earlier time than the Danish Social

Democrats, with whom, for instance, contracting-out of welfare services is still strongly contested.

The paper starts with a short overview of the NPM literature and the arguments put forward about variation in the extent of NPM reforms. It then develops a theoretical argument as to why party strategies and especially the strategy of the Social Democrats should matter for extent of NPM reforms.

4

This is followed by an explanation why Denmark and Sweden are good cases in which to explore this and what is meant by market-type reforms. The next section offers a discussion of the extent of such reform in the four areas in the two countries. The paper continues with an outline of the NPM reform debate in the two countries with special focus on the strategy of the social democratic parties. The concluding section of the paper discussed the implication of the theoretical argument and the prospects for generalizing the argument.

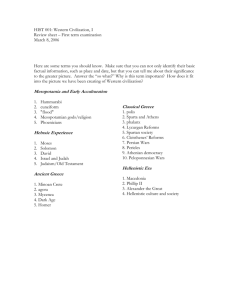

The NPM debate and why party politics should matter

As mentioned above, the scholarly debate about NPM reforms has increasingly focused on the question of variation in the extent to which different countries have implemented such reforms. Four types of factors are normally discussed as explanations for variation (cf. Hood 1996, Olsen &

Peters 1996, Wright 1994, Pollitt & Summa 1997, and Peters 1997):

The first group is macroeconomic factors. The macroeconomic troubles that hid the OECD countries in the 1970s are one of the reasons why

NPM reforms have reached the political agenda in these countries. The extent of macroeconomic troubles have, however, varied across the OECD countries and one hypothesis about NPM reforms would be that the countries that have faced the biggest macroeconomic troubles have implemented the largest extent of NPM reforms.

The second group of arguments is about party politics. NPM reforms are often seen as part of the neo-liberal agenda of the 1980s, and a second hypothesis about variation in NPM reforms would be that they have been implemented to a larger extent in countries and at times with right-wing governments.

The third group of arguments relates differences to different administrative cultures stemming from different “state traditions”. Peters

(1997) contends that the Anglo-American tradition is more receptive to marked based reforms, such as NPM reforms, than it is the case in particular the Germanic tradition (cf. also Rhodes 1999 and Loughlin & Peters 1997).

Along these lines, Clarke (2000) stresses the importance of different statist

5

and legalistic values in explaining variation in the extent of NPM reforms in

Germany, France and Britain.

The fourth group of arguments relates variation to different political institutions. These may be found at two levels. First, macro-institutional differences such a majoritarian vs. consensus systems may result in different degrees of NPM reforms (cf. Yesilkagit & de Vries forthcoming, Pollitt &

Summa 1997, and Barlow et al. 1996). Second, differences may be due to

“micro-institutional” differences. For instance, Christiansen (1998), points to the power of public-sector unions as part of the explanation for the limited extent of market-type reforms in Denmark. As done by Christensen and

Pallesen (2001), this argument about micro-institutional structures can also be applied to explain differences in the extent to which different types of NPM ideas are implemented. For instance, it has proved much easier to delegate financial authority to lower level administrators than to introduce contractingout because public employees will oppose the latter type of reforms.

In addition to the focus on the strategies of the social democratic parties, an argument of this paper is that NPM reforms often needs to be seen within the broader context of welfare-state reforms. Most of the literature on NPM reforms analyzes them as public administration reforms.

However, when it comes to reforms such as the introduction of quasi-markets in the health-care sector or private providers of elderly care, NPM reforms become part of the political battle over the welfare state. This need to analyze

NPM reforms within a welfare-state context is particularly important when dealing with the Scandinavian countries. The literature on different welfarestate regimes (Esping-Andersen 1990, 1999 and Huber & Stephens 2000) has documented that countries differ considerably in the extent to which they offer their citizens social services such as elderly care and childcare and also very much in the way such services are provided. In Scandinavia, such services are extensive and publicly funded and provided, whereas in

Continental European countries such services are less extensive, publicly funded, but generally not publicly provided. The implication of these differences for the NPM debate is clear. The public sector, which should be reformed along NPM lines, is different from country to country. In

6

Scandinavia, the public sector includes the extensive service welfare state and, therefore, NPM reforms must be analyzed within the broader welfarestate context.

In the wake of Pierson’s (1994 and 1996) seminal work, welfare-state retrenchment - or reforms - has attracted a lot of scholarly interest. This debate has been detached from the debate about NPM reforms and has with a few exemptions (e.g. Clayton & Pontusson 1998) not paid much attention to welfare services. As argued by Ross (2000b), the debate has also not paid much attention to party politics, yet a number of studies have increasingly done so (Ross 2000a, Kitschelt 2001, and Green-Pedersen forthcoming(a)).

Furthermore, these studies emphasize that partisian effects are more complex than implied by the argument that welfare-state retrenchment is the result of right-wing incumbency. The theoretical aim of this paper is to show that the recently developed arguments about partisian politics and welfarestate retrenchment are also relevant for the understanding of variation in NPM reforms. As mentioned above, the attention within the NPM-literature to party politics has been limited to the question of the importance of right-wing incumbency. However, a few scholars discussing the Swedish experience have actually pointed to the strategy of the Swedish Social Democrats (Pierre

1993, Premfors 1998, see also Schwartz 1994).

The starting point for the argument about partisian effects on the extent of NPM reforms is the literature on agenda-setting and especially framing of political issues (Riker 1986, Jacoby 2000, cf. also Stone 1997). As

Schattschneider (1960, 68) argued, “the definition of alternatives is the supreme instrument of power”. The issue of NPM reforms can be framed in rather different ways with important consequences for their political attractiveness. Opponents of NPM reforms can be expected to portray them as part of a neo-liberal attempt to dismantle the welfare state. They are just a disguise for cutbacks in the welfare state and will lead public services of a lower quality. Proponents of NPM reforms will argue that they lead to more efficient services provision and thus the possibility of services of the same quality but at lower costs or better services at the same costs. Furthermore, proponents will try to argue that NPM reforms is a way of fighting a

7

bureaucratic “nanny state” for instance by providing consumers with a greater choice of services. For politicians the attractiveness of NPM reforms depends very much on their possibilities of framing NPM reforms in the latter way. If introducing NPM reforms will be seen by the electorate as an attempt to provide citizens with better and cheaper services as well as more choice, politicians may find them attractive. Yet, if such reforms are seen as part of an ideological attack on the cherished welfare state, politicians will not find them attractive. NPM reforms become the politics of blame avoidance

(Weaver 1986 and Pierson 1994).

The question then is what determines the way the NPM issue is framed. This is where party politics becomes important. Using the idea of issue-ownership or issue-association (Budge & Farlie 1993 and Ross 2000a), one can argue that the welfare state issue is owned by social democratic parties in the sense that the electorate sees social democratic parties as the true proponents of the welfare state. Right-wing parties are seen as more preoccupied with keeping down taxation and managing the economy. The implication of the social democratic ownership of the welfare-state issue is that the way they approach NPM reforms is crucial for the way the issue is framed. If social democratic parties oppose NPM reforms as an ideological attack on the welfare state, right-wing parties will find it very hard to portray

NPM reforms along the positive lines. On the other hand, if social democratic parties embrace NPM reforms as a way of renewing and improving the welfare state, a consensus around a positive NPM story may emerge making it much more attractive to implement them.

Summing up, the theoretical argument is that the strategy of social democratic owners of the welfare state is crucial because it determines whether NPM reforms are framed in a way that makes them politically attractive to implement.

Research design

8

Having outlined the theoretical arguments of the paper, the choice of

Denmark and Sweden as the two cases for investigation can now be defended. Both countries are prime examples of the Scandinavian service welfare states (Huber and Stephens 2000), and the public sector in the two countries is thus basically the same thing (cf. Lane 1997) The implication of this is that the “micro-institutions” in the two countries are largely similar. For example, both countries have very strong public sector unions. The macropolitical institutions are also largely similar, just as both countries belong to the Scandinavian administrative culture (Loughlin and Peters 1997). Finally, in both countries, the welfare state has faced dire economic straits within the last 20 years, although the sequence of the economy has been somewhat different. In Denmark, the economy was “at the brink of the abyss” in the early

1980s, then recovered somewhat in the 1980s and early 1990s before doing very well in the last part of the 1990s (Nannestad and Green-Pedersen forthcoming). The Swedish economy did somewhat better than the Danish one in the 1970s and 1980s, but then witnessed a meltdown in the beginning of the 1990s, from which it has recovered quite quickly (Hemerijck and

Schludi 2000). Altogether, most theoretical arguments about NPM reforms would not predict any difference in the extent of NPM reforms between

Denmark and Sweden. Yet, arguments about party politics would. Arguments linking NPM reforms with right-wing incumbency would predict Denmark to have gone furthest in terms of NPM reforms. The reason is that Denmark had right-wing governments from 1982 to 1993, whereas the right-wing government in Sweden from 1991 to 1994 has been the only such government since 1982. The theoretical argument about the strategy of the

Social Democrats would predict just the opposite. In both countries, the welfare-state issue is clearly owned by the social democratic parties, yet as will be argued below, the social democratic parties in the two countries have founded themselves in different political situations and have embraced the question of NPM reforms differently.

The other question in relation to the research design relates to the investigation of the extent of NPM reforms. Following Pollitt and Summa

(1997), it is useful to distinguish between different dimensions of the NPM

9

agenda. They highlight six dimensions, namely privatization, marketization, decentralization, output orientation, traditional restructuring, and the intensity of the reform process. Focus in the following will be on marketization, or what the OECD (1993) describes as “market-type reforms”. The gist of this dimension is the introduction of the characteristics of a market, most importantly competition, but also, for example, pricing in the public sector.

Examples of such reforms are contracting out, voucher systems, internal markets, and user fees (cf. Pollitt & Summa 1997, 8 and OECD 1993).

Furthermore, focus in the following will be on the introduction of such reforms in four core welfare services namely, health care, elderly care, childcare and primary schools. The reason for focusing on market-type reforms of these areas is that these are often the most controversial part of the NPM agenda.

As argued by Christensen and Pallesen (2001), some NPM reforms such as delegation of financial authority can be implemented without much political opposition. However, introducing market-type reforms in relation to welfarestate services is likely to attract significant political attention and is therefore an area where the effects of party politics should be visible.

Market-type reforms of welfare services in Denmark and Sweden

In the following, the extent of market reforms in the four service areas will be discussed area by area. At the end of the section, the extent of NPM reforms more generally in the two countries will shortly be discussed. The idea is to see whether there is any indication that a focus on different NPM reforms would have resulted in a different conclusion about the two countries.

Market-type reforms of the health care sector

Both Denmark and Sweden are examples of the public integrated model of health care were services are financed through general taxation and publicly provided. Furthermore, in both countries health care is decentralized as the responsibility for provision is placed with the counties. Yet, some differences exist. First, Denmark has a family doctor system where the patients are allowed to choose their own doctor, and the doctors are self-employed. Yet, the government regulates the number of general practitioners, so competition

10

is very limited. Sweden has no family doctor system and general practitioners were public employees. Furthermore, patients had no right to choose primary health care. Second, in Sweden, limited user fees have long existed whereas health care in Denmark is completely free (Saltman and Figueras 1998). In both countries, the health care system has been heavily debated in the 1980s and 1990s. In the 1980s, the focus was very much on costs containment, whereas focus in the 1990s has shifted to other questions such as avoiding waiting lists (Blom-Hansen 1998). However, when it comes to market-type reforms of the sector, the two countries differ.

In Sweden, reforms of the health care sector began in the 1980s with other types of NPM reforms such as the delegation of financial responsibility from the counties to lower administrative levels, such as hospitals, and the introduction of global budgets (Anell 1996, Anell & Svarvar 1995, and

Diderichsen 1995). The more market-oriented reforms have been introduced in the 1990s and can divided into three types: splitting providers and purchasers, free choice for the patients, and reforms of primary health care including more room for private alternatives (cf. Blomqvist and Rothstein

2000, 192-198).

The general idea behind splitting providers and purchasers is that boards with political representation buy health care services from providers who, even though they are still public, compete with each other. The payment to the provider is generally production based (Diderichsen 1995). The number of boards in each county buying health care services varies from 1 to around

15 (Anell & Svarvar 1995, Anell 1996, and Rehnberg 1997). Today, the majority of Swedish counties have split the provider and purchaser role (SOU,

2000:3, 146).

Before 1991, Swedish patients had no right to choose neither hospital nor primary care. This has changed. All Swedish counties allow a free choice of primary care and most of them also a free choice of hospital including hospitals in other counties (Anell 1996). These changes have been most powerful in the more densely populated southern and western part of Sweden

(Garpenby 1995). The possibilities of choosing health care without reference varies across counties, but in a number of counties the possibilities are quite

11

extensive (Svensson and Nordling 1995). Finally, in 1994, patients were also given the right to choose a family doctor, private or public, but this system was abolished again when the Social Democrats regained power (Rehnberg

1997, and Blomqvist 2000).

Private practitioners have also gained a stronger foothold in primary health care. Some private practitioners had always existed in the major cities and in the beginning of 1994, the non-socialist government introduced the free right of private practitioners to establish themselves. As patients were guaranteed public reimbursement, competition was thus introduced in primary health care. Upon returning to government, the social democrats also reversed this reform, but allowed the private practitioners that had already established themselves to continue (Rehnberg 1997, and Blomsquist 2000).

In 1998, the number of visits in primary health care to a private doctor had increased to almost 20% of all visits (SOU, 2000:3, 146).

In Denmark, other types of NPM reforms such as the delegations of financial authority and global budgets have also been introduced (Pallesen

1997 and Christensen & Pallesen 2000). However, more market-type reforms have been very limited. There has been no introduction of provider/purchaser models, the organization of the primary health care sector has remained largely unchanged, 1 and user fees have hardly been discussed. Furthermore, visiting a hospital or specialist without a reference from a general practitioner is still largely impossible in Denmark (cf. Pallesen & Pedersen forthcoming and Vrangbæk 1999). The only significant market-type reform of Danish health care is the right in principle of the patient to choose a hospital in a different county, which was introduced in 1992. However, since the counties decide themselves how hospitals are paid for treating patients from a different county and a hospital can reject a patient from another county, the right of the patient is in practice more limited, yet not without content (Vrangbæk 2000).

In summary, as argued by Pallesen and Pedersen (forthcoming), if the Danish health care system is unique, the uniqueness has to do with the lack of reforms.

1 The only change is that patients can now change family doctor all the time and not just at the beginning of a new year.

12

Comparing market-oriented health care reforms in the two countries.

Sweden has, as also argued by Sahlin-Andersson (1999, 301) gone further than Denmark, which has hardly gone anywhere. Compared to Denmark,

Sweden has introduced purchaser provider models and increased role of private doctors implying more competition in primary health care. User frees in Swedish health care have also been increasing the 1990s where the counties have been given more freedom to choose the level of the fees

(SOU, 2000:3, 146). Both countries have introduced free choice of hospitals for the patient, yet in both cases with some limitations. The Swedish reforms do clearly not represent a revolution of the health care system (cf. Anell

1996), yet as argued by for instance Rehnberg (1997) and Blomqvist (2000), the reforms in Sweden have been substantial, which is not the case in

Denmark.

Market-type reforms of elderly care

Both the Swedish and the Danish welfare state offer extensive elderly care in the form of home help, residential homes, or sheltered housing. Traditionally, a decentralized public integrated model has also dominated elderly care in both countries. Local governments have provided the care and financed this out of general taxation.

2 In the 1990s, Sweden has taken some steps away from the model, which has not happened in Denmark

In 1992, a reform of Swedish elderly care, “Ädelreformen”, transferred elderly care from the counties to the municipalities. Since then, the municipalities have implemented market-type reforms of two kinds

(Szebehely 2000). First, the Swedish municipalities have implemented the same kinds of provider purchaser reforms as the counties have done in health care. The tasks of deciding the level of care, estimating the needs, and supervising the provision have been separated from the actual provision.

Today, the majority of the Swedish municipalities have implemented such reforms (SOU 2000; 3, 174-175, Socialstyrelsen 1999). Second, an increasing number of Swedish counties have started buying care from private

2 In Denmark, independent institutions have long played a role in elderly care. These institutions are in principle private, but in reality they are integrated into the public sector and do not constitute an element of competition (Bertelsen 2000, 77-80).

13

firms. In 1999, 9% of the Swedish elderly were cared for by a private firm compared to 3.5% in 1993 (Socialstyrelsen 1999, 7). Either the municipalities contract out the whole operation of residential homes, home help or sheltered housing or they buy places in institutions set up buy private providers.

3 In

1999, around 25% of the Swedish municipalities had contracted out part of the operation of home help, residential home or sheltered housing to private firms including all municipalities with more than 100.00 inhabitants

(KommunAktuellt 1999, and Socialstyrelsen 1999, 26-28).

4 Around 40% of the municipalities bought places in institutions set up by private providers

(Socialstyrelsen 1999, 34-35). These figures do not indicate that private firms have taken over Swedish elderly care, but they have gained a foothold and today several major private firms operate within Swedish elderly care with a turnover of several hundred million Swedish kroner (KommunAktuellt 1999,

Socialstyrelsen 1999).

In Denmark, the organization of elderly care is more or less unchanged. There are examples of contracting out of both home help and residential homes, as well as models where the elderly have been offered the choice between public and private providers, yet the examples are literately few. (Bertelsen 2000, Institut for Serviceudvikling 1999 and Det Kommunale

Kartel 1999). Purchaser provider models are also unknown within Danish elderly care (Institut for Serviceudvikling 1999). Altogether, market-type reforms of the Danish elderly care sector amounts to a couple of cases of contracting out receiving lot of public attention, but the market has not gained a foothold in the provision of Danish elderly care.

Summing up, market-oriented reforms of elderly care are more extensive in Sweden than in Denmark. This does not mean that a revolution has happened in Swedish elderly care, but market-type reforms have been implemented in a large part of the Swedish municipalities which is not the case in Denmark. Finally, user fees for home help have been increasing in

3 In terms of the number of people cared for, contracting out is the more important of these two kinds, covering 80% of the elderly cared for by private providers and it is the kind that is increasing (Socialstyrelsen 1999, 40).

4 In most cases the whole operation has been contracted out, but in some cases only parts of it such as the provision of food has been contracted out (Socialstyrelsen 1999, 27).

14

Sweden, whereas home help in Denmark is still mainly for free (Szebehely

2000).

Market oriented reforms of childcare

From the 1960s and onwards, both Denmark and Sweden have expanded day-care for children of preschool age considerably and this expansion has continued even during the times of economic troubles in the 1980s and 1990s

(Blom-Hansen 1998). As with other welfare services, the responsibility of provision has been decentralized, in the case of childcare to the municipalities. They finance childcare out of general taxation; yet, in both significant user fees exist, but vary from municipality to municipality. The care is traditionally provided in either public institutions or by private persons in their own homes.

5

In Denmark, market-type reforms of childcare were discussed from

1982 and onwards. After a long and tough debate, an amendment to the social service act was passed in 1990 which made it possible for the municipalities to provide financial support for private persons or organizations setting up childcare outside the control of the municipalities and thus introducing competition (Damgaard 1997 and 1998, chap. 6). Only a limited number of these “pool schemes” have, however, been established, carrying for only around 2% of the children in 1999 and the figure is not increasing

(Danmarks Statistik, Statistiske Efterretninger 1997:5, 15 and 2000:12, 19).

Furthermore, the new social service act passed in 1997 has allowed contracting out of childcare institutions, but only very few examples can be found (Borchorst 2000 and BUPL 2000). In summary, market-type reforms of

Danish childcare have been very limited.

In Sweden, the possibility of other than public provision of childcare was introduced in the 1980s. Until 1992, only non-profit providers were allowed, but in 1992, it was also allowed for the municipalities to provide financial support for childcare provided by profit-maximizing firms (Montin

5 These private persons are employed and supervised by the municipalities. Thus, there is not element of private competition involved. Just as in elderly care, Denmark has a tradition for independent institutions in childcare. However, apart from different pedagogical principles in some of these independent institutions, there is hardly any difference from public institutions and these institutions do not constitute an element of competition (BUPL 2000).

15

1992 and Montin & Elander 1995). In the 1980s, the Swedish municipalities did not use the new possibilities very much (Montin 1992), but in the 1990s, alternative provision has increased significantly. Thus, in 1999 13% of the

Swedish children younger than 6 cared for received care from a private provider (Skolverket 2000a, 12-16). In around half of the cases, private provision is organized by parents’ associations. Private profit-maximizing firms constitute around 25% of the cases (Skolverket 2000b, 23).

Comparing, the experience of the two countries in the childcare sector, market-type reforms have once more been more widespread in Sweden. For instance, where less than 10 examples of childcare run by private firms can be found in Denmark (BUPL 2000), in 1999, Sweden had 278 childcare institutions run by private profit-maximizing firms (Skolverket 2000b, 23).

Finally, as in other service areas, user fees in Swedish childcare have been increasing which is hardly the case in Denmark (Lehto et al. 1999). Again what has happened in Sweden is not a revolution, but also in childcare, market-oriented ideas have, unlike Denmark had an impact.

Market-type reforms of primary schools

Primary schools constitute the service area where the historical differences between the two countries are the greatest (Lindbom 1998). Both countries have public and tax-financed school systems, but there are important differences. From the perspective of this paper, the most important difference relates to the role of private or independent schools. These schools have a long tradition in Denmark whereas their importance in Sweden has historically been limited. Independent or private schools in Denmark are financially dependent on public support as the user fees only cover around 15% of the operating costs (Christiansen 1998) and have to abide government regulation concerning tests etc (Christensen 2000, 200). However, they still provide parents with a choice of schools, which Swedish parents have historically not had, and thus constitute an element of competition. In the mid 1980s, 8.9% of

Danish school children attended these schools (op. cit., 210).

6

6 Other differences between the two countries are that the Swedish school system has historically been much more centralized, and that user boards, which have been mandatory in

Denmark since 1970, have never existed in Sweden (Lindbom 1995).

16

Market-type reforms of Danish primary schools have hardly taken place. For instance, the possibilities of Danish parents of choosing a different public school from the one allocated by the municipality still remains very limited in practice (Christensen 2000). In the 1980s, an entrepreneurial minister of education pursued other type of NPM reforms. Most importantly, he tried to strengthen user influence, but his reforms efforts largely failed

(Christensen 2000 and Christensen & Pallesen 2001). This may be one of the reasons why the percentage of schoolchildren in private schools has increased to 12% (Statistiske Efterretninger, Uddannelse og Kultur 2000:10).

As in other areas, the reforms of Swedish primary schools started in the 1980s with other NPM reforms such as decentralization. The municipalities gained much more influence on the primary school system, as they have also had in Denmark (Lindbom 1995, 64-

74 and Lidström &

Hudson 1995). In principle, Swedish parents were also given the right to choose which public school their children should attend (Lidström 1999,

139).

7 In the 1990s, the Swedish primary school system has witnessed other market-type reforms. In 1992, the right-wing government introduced a voucher system giving parents the right to choose between public and private schools. If the parents would choose a private school, the voucher had the value of 85% of the average costs of a pupil in a public school. In 1993, private schools were also given the opportunity of charging reasonable user fees. After returning to government power, the Swedish Social Democrats, however, abolished this possibility. They also decreased the value of the voucher to 75% of the public costs, but from 1996, the law stipulates that the voucher should be equal to the costs per pupil in public schools (Blomqvist &

Rothstein 2000, 162165 and Lidström & Hudson 1995 19-25). Some of the

Swedish municipalities have responded to the national regulation by promoting both independent schools and stimulating parents to actively choose between schools. The number of municipalities with such policies has, however, decreased in the end 1990s compared to the beginning of the

7 The latest available figures concerning this are from 1996 showing that 7% of the Swedish parents make use of this opportunity (Blomqvist and Rothstein 2000, 165).

17

1990s (Lidström 1999).

8 The percentage of Swedish school children attending independent or private schools has increased in the 1990s, but still remains at a very low level, with only 3.4% of the pupils attending such schools in 1999

(Skolverket 2000b, 88).

Comparing, the two countries in the primary school area is more difficult than in other areas because of the different starting points. Markettype reforms have been introduced in the Swedish primary school system, but unlike the other areas, they seem to have lost momentum towards the end of the 1990s. In Denmark, hardly any market-type reforms have been introduced in the primary school system, but some of the Swedish reforms have been policy in Denmark for a long time. The number of children attending private or independent schools in Denmark is thus still much higher than in Sweden.

The four areas seen as one and the broader impact of NPM

If one looks at the four above-discussed areas as one, the picture is that market-type reforms have been more extensive in Sweden than in Denmark.

This conclusion holds true for health care, elderly care and childcare, and to some extent also for primary schools. Yet, in the latter case, the picture is less clear because of different starting points of the two countries, and because primary schools seems the area of the Swedish welfare state affected the least by market-type reforms. The analysis conducted thus confirms Christiansen (1998) conclusion about Denmark that market solutions to problems of public sector governance was a “prescription rejected”. In relation to the Swedish case, the report of the government commission investigating the current state of the Swedish welfare state (Kommitté

Välfärdsbokslut), describes the 1990s as the “decade of the market” in relation to welfare services (SOU, 2000; 3 178-184). As explained above, it would be to overstate the case to argue that a revolution has taken place in

Sweden, but market-type reforms have gained a foothold in the Swedish welfare services (cf. Forssell 1999 and Svensson), which is generally not the case in Denmark.

8 In the period 1991 to 1994, 22% of the Swedish municipalities stimulated the growth of independent schools and 32% stimulated parents to actively choose a school. For 1994 to

1998, the figures were 6% and 21% respectively (Lidström 1999, 149).

18

As explained above, market-type reforms are but one type of NPM reforms, which can also be implemented in other areas than the four welfare services discussed above. In the following the more general impact of NPM reforms in the two countries will shortly be discussed. As mentioned above, the idea is to see whether there is any indication that a focus on different aspects of the NPM agenda would have resulted in a different conclusion about the two countries.

Starting with Denmark, analyses of the more general impact of NPM reforms confirm the picture found above, namely that NPM reforms are relatively few in Denmark (Pollitt 1996, Hood 1996 and Klausen 1998). The non-socialist governments from 1982 to 1993 launched a number of ideas about NPM reforms under the heading of a modernization program for the public sector (Bentzon 1988). A new budgetary system for the central government was introduced (Christensen 1992), but other elements such as a deregulation campaign and strengthened user influence in welfare services largely failed (Christensen 1991 and Christensen Pallensen 2001). However, in the later part of the 1990s, Denmark has seen two types of NPM reforms.

First, central government has increasingly used contracts to govern a number of state institutions like museums, research libraries etc (Greve 2000).

Second, in the same period, there has been a wave of corporatization of state enterprises in some cases being followed by privatization. The most conspicuous example is the privatization of the national telecommunication firm, TeleDanmark, in 1997/1998 (Christensen and Pallesen 2000).

Generally, Sweden seems to be one of the countries where NPM ideas have had a fairly strong impact (Pollitt & Summa 1997, and Premfors 1998,

153), and the general impact thus seems greater than in Denmark (Montin

1997, Hood 1996, and Schwartz 1994). Sweden has also witnessed corporatizations (Berg 2000), and privatization of the same scale as in

Denmark (OECD 1999, 130), without including the recent selling of shares in the Swedish telecommunications firm, Telia. Furthermore, Sweden has undertaken NPM reforms such as the introduction of competition in the labor market exchange and deregulation of the taxi system (Svensson 2000) that

19

have no happen in Denmark.

9 These are, of course, only indications of the more general impact of NPM reforms, yet they do seem to confirm the picture found when looking at market-type reforms in the four welfare service areas.

Different strategies of the social democratic parties

As explained above, the theoretical argument of this paper is that differences in the extent to which countries have implemented NPM reforms are caused by different strategies of the social democratic parties towards welfare-state reforms in general and NPM reforms in particular. In the following, the aim is thus to show that the strategies of the social democratic parties in the two countries have differed and how this has caused a different debate about

NPM reforms.

In Denmark, the question of welfare state reforms including NPM reforms of welfare services entered the public agenda with the coming to power of the non-socialist government in 1982. During the 1970s, the Danish economy deteriorated steadily and Denmark moved to “the brink of the abyss”

(Nannestad and Green-Pedersen, forthcoming). In the autumn of 1982, the social democratic government simply gave up and handed over government responsibility to a non-socialist government. Shortly after, the new government launched a privatization program including market-type reforms of welfare services (Greve 1997 and Kristensen 1987 & 1988).

The privatization program was met stiff resistance from the Social

Democrats and the trade unions. The general strategy of the Social

Democrats was to attack the new government by portraying its policies as an ideological attack on the welfare state (cf. Green-Pedersen 2000, chap. 9).

This was also the strategy the Social Democrats followed in relation to the question of privatization and market-type reforms of welfare services. As the social democratic spokesman put it in a debate in the Danish parliament about the privatization program “We do not perceive privatization as an endeavor to achieve greater efficiency, but as an endeavor to cut back by creating inequality. It runs contrary to our perception of human nature, and so we will reveal and fight such endeavors to put the clock back” (cited from

9 Competition in the Danish labor market exchange is currently under discussion.

20

Kristensen 1988,13). As argued by Kristensen (1988, 13-14), the Social

Democrats were successful in establishing the premises of the debate along these lines, namely privatization as a basic attack on the welfare state.

Privatization and market-type solutions were defined as an ideological crusade against the welfare state, and the privatization program was dead before it started (Greve 1997, 37-38). After this failure, the government launched the more modest “modernization program”, but as mentioned above, the ideas also largely failed. As exemplified by the attempts of markettype reforms of childcare, strong political resistance from the Social

Democrats and the trade unions made such ideas politically very difficult to implement (Damgaard 1997). In most cases, the non-socialist governments put NPM proposals back in the drawer as the Prime Minister literately did with a privatization proposal from his own party in 1983 (Dyremose 1999).

In 1993, a social democratic led government took over and social democratic led governments have ruled Denmark since then. As in other areas (cf. GreenPedersen 2001), a “Nixon goes to China” dynamic (Ross

200a) characterizes the area of NPM reforms. Reforms such as privatizations, corporatizations and the establishment of contract agencies started slowly under the last non-socialist governments, but have been speeded up significantly under the social democratic led governments (Christensen &

Pallesen 2000 and Greve 2000).

In relation to market-type reforms of welfare services, the situation of the Danish Social Democrats has proved rather difficult. The difficulties stem from the decentralized nature of the Danish welfare state. Even though central government guidelines are important, it is local politicians who have to actually implement market-type reforms of the welfare services. As a way of example, allowing contracting out of childcare has not led many municipalities to do so. The Social Democrats are caught in their own rhetoric from the

1980s. The definition of market-type reforms as an ideological crusade has not made such reforms attractive for local politicians. Therefore, the social democratic leadership has on two occasions tried to pursued the rest of the party, including local politicians, to pursue a more pragmatic line towards especially contracting out, but the leadership has in both cases lost the battle

21

(Bille 1999). In Denmark, market-type reforms are still seen as an attack on the basic principle of the welfare state and not as a tool to achieve cheaper and/or better service.

10

In Sweden, the debate about NPM reforms and market-type reforms in particular has developed along different lines. The issue of public sector reforms seriously entered the political agenda when the Social Democrats regained power in 1982. The SAP had long felt vulnerable to attacks from the non-socialist parties for having created a bureaucratic nanny state. This feeling of vulnerability was fueled by the economic problems following in the wake of the second oil-crisis, even though it took a decade before Sweden experienced the same urgent economic crisis as Denmark did in the beginnings of the 1980s. The social democratic government put public sector reforms on the top of its agenda and launched a special “public administration policy” including a ministry to take care of the issue (Premfors 1991,

Gustafsson 1987, and Pierre 1993).

During the first years, the content of “public administration policy” in

Sweden was mainly decentralization and a more service oriented welfare state. The strategy of the SAP was that such reforms would prevent more market-type reforms from reaching the political agenda (Antman 1994, 36).

As exemplified by the ban on profit-maximizing firms in childcare, the SAP generally rejected market-type reforms with arguments very similar to the

Danish Social Democrats (Rothstein 1993, 501-505). However, during the

1980s, criticism also from within the SAP grew that the government was not doing enough to reforms the Swedish public sector (Antman 1994, 38-42).

Thus, after the election in 1988, the Ministry of Finance was given a more central role and this put market-type reforms on the agenda. As documented in Schüllerqvist’s (1996) analysis of the debate about primary schools, the

SAP now accepted the basic content of the nonsocialist parties’ suggestions about market-type reforms. In the budget Bill for 1990, principal reservations against market-type reforms of welfare services were given up (Premfors

10 This is amply illustrated by a recent and fierce debate about contracting out in Denmark.

The debate has been started by the Liberals who want to use money saved from contracting out for tax relieves. This time the leadership of the social democratic party has chosen the negative line towards the issue because it sees it as a way of attacking the liberal party.

22

1998), and the Swedish government published several reports arguing for the need for competition within the public sector (Antman 1994, 42-44).

11

In 1991, SAP suffered a historic defeat in the election which paved the way for a non-socialist government. At the same time, the Swedish economy experienced a meltdown. This situation opened a window of opportunity for the non-socialist parties. The Social Democrats had already admitted that the

Swedish welfare state needed to be reformed also in a market-oriented way and the economic crisis added fuel to this fire. Thus, the non-socialist parties implemented more radical market-type reforms. The SAP was not enthusiastic about these reforms, and when the party regained power in

1994, it reversed some of these reforms (cf. above). However, the Social

Democrats have continued to pursue public sector reforms (Premfors 1998 and Svensson 2000). Thus, as a number of authors argue (e.g. Montin 1997,

264, Håkansson 1996, 60, Blomqvist, 2000, and Antman 1994, 44-45), the market-type reforms implemented by the non-socialist government from 1991-

1994 followed a path that had been laid out by the Social Democrats. The latter had admitted that the public sector was “part of the problem not the solution”, as Antman put it (1994, 20). Summing up, the Swedish debate about NPM reforms proceeded along different lines from the Danish debate.

In Sweden, the debate became one of reforming an ineffective welfare state leaving little choice for the citizens (cf. Rothstein 1993 and Boreus 1997, 263-

265). Thus, as argued by Huber and Stephens (1999, 14), for once the SAP actually lost a debate about the welfare state.

Before turning to the conclusion of this paper, two points deserve some further discussion, namely the relationship between central and local politics and the reasons for the different strategies pursued by the social democratic parties in the two countries.

In both Sweden and Denmark, the service welfare state is very decentralized with the counties and municipalities as the actual organizers of the services and in most areas with a considerable independence from central government (Albæk et al. 1996). Thus, even though central government regulations are important for the possibilities of implementing

11 Instructive reading about the developments within the SAP is the memoirs of the former

23

market-type reforms, it is largely the Swedish counties and municipalities that have implemented such reforms and their Danish counterparts that have chosen not to do so. Nevertheless, the argument of this paper is that the difference between the two countries has its roots in developments at the national level. The national level is important for what goes one at the local level beyond simply framing rules within which local governments operate.

Politics at the local level is strongly influenced by politics at the national level

(cf. Thomsen 1998). In relation to market-type reforms, the way the national debate about this issue has been framed affects whether or not local politicians find it attractive to implement such reforms. In Denmark, markettype reforms have come to be seen as part of an ideological attack on the welfare state and this has caused local politicians, who are generally known to be much less interested in ideological questions than national politicians, to shun such reforms. In Sweden, where the issue has been framed as one of choice for the citizens, local politicians have found market-type reforms much more attractive. Of course, an interesting question to pursue further is why some counties and municipalities have chosen to implement market-type reforms and others not. A number of studies have already investigated this question (Bertelsen forthcoming and Christoffersen & Paldam forthcoming on

Denmark and Lidström 1999 and Montin 1997 on Sweden). Interestingly from the perspective of this study, none of these studies find that market-type reforms is something particular for counties and municipalities governed by non-socialist parties.

The second question is why the social democratic parties in the two countries chose different strategies towards the question of NPM reforms.

The fact that the Danish Social Democrats found themselves in opposition whereas the Swedish Social Democrats were in government when the question reached the political agenda is important in this regard. Being in opposition, the Danish Social Democrats could attack the non-socialist governments for implementing unfair welfare-state reforms in general without having a responsibility for finding solutions to the problems of the public sector (cf. Green-Pedersen 2000). When the Danish Social Democrats

Minster of Finance, Kjell-Oluf Feldt (1991).

24

reentered government in 1993, the problems of the public sector became their problems and as explained above, this has also led to a more open mind towards NPM reforms. When the Swedish Social Democrats reentered government in 1982, they knew that the problems of the public sector were their problems and this continued in the 1980s. Therefore, rejecting NPM was much less attractive for the SAP. Furthermore, the Swedish Social Democrats have dominated government more than their Danish counterparts and their ownership of the welfare-state issue is thus stronger. Therefore, problems of the welfare state in Sweden are problems of the Social Democrats to a larger extent than it is the case in Denmark. Finally, another factor, which is not necessarily in accordance with the theoretical argument of this paper, may have played a role. The degree of decentralization and use democracy in the two countries has differed, as exemplified by the primary school system

(Lindbom 1995, cf. also Knudsen and Rothstein 1994). Thus, criticizing the

Swedish welfare state for being paternalistic and leaving no choice for the citizens has been easier than criticizing the Danish welfare state for the same ting.

Altogether, the more positive approach towards NPM reforms in general and market-type reforms in particular of the SAP is not the result of a political blunder. There were good tactical reasons why the SAP chose this strategy. If the SAP made any blunder, it was perhaps that they were too slow to accept market-type reforms and thus giving the non-socialist parties too good possibilities of criticizing the welfare state. As argued by Rothstein

(1993, 501-505), when the SAP officially accepted market-type reforms, it was too late

Conclusion

Put briefly, the argument of the paper is that in order to understand why countries implement NPM reforms to a different extent, the strategies of the social democratic parties must be taken into account. The different strategies of the Danish and Swedish Social Democrats explain why market-type reforms of welfare services are more widespread in Sweden than in Denmark.

In this concluding section, a number of implications of this argument will be

25

discussed along side with a number of questions relating to generalizing the argument.

The first implication of the argument is that the literature on NPM reforms should pay more attention to party politics. As explained above, most of the other scholarly writings about NPM reforms have focused on various political institutions, economic troubles and administrative traditions. The impact of party politics is, however, more complicated than seeing NPM reforms as an initiative by right-wing parties. In this way, the argument of this paper parallels an argument made in relation to retrenchment of transfers

(Green-Pedersen forthcoming(a)) that studying systems of party-competition is important for understanding variation in welfare-state reforms.

It is also worth emphasizing that the implication of the argument put forward in this paper is not that welfare-state reforms are easy to implement.

Pierson (1994) has put forward a number of plausible arguments why welfarestate retrenchment is the politics of blame avoidance, and for instance

Christensen and Pallesen (2001), Christiansen (1998), and Bertelsen (2000) have pointed to factors such as residence from public employees and riskadverse and control maximizing politicians making NPM reforms and especially market-type reforms politically dangerous. These arguments about the politics of reform are plausible. Yet, it is important that they do not prohibit a search for the political conditions under which reforms can take place as conducted in this paper.

Another implication of this paper is that NPM reforms should not just be studied as public administration reforms, but must be seen within the broader context of welfare-state reforms. In both Denmark and Sweden, such a broader approach is necessary in order to understand the different strategies pursued by the social democratic parties in the two countries. The importance of this implication, however, varies depending on the type of NPM reforms one studies. Some NPM reforms such as reforms of management principles and wage-systems are reasonable to study as public administration reforms, which normally do not attract the same kind of attention from political parties as welfare-state reforms. However, as exemplified by market-type

26

reforms in this paper, other types of reforms are much more than public administration reforms.

The final question to be addressed is about generalizing the argument of this paper to other countries. In this regard, it is first of all important to be aware that a focus on market-type reforms of welfare services is less obvious outside Scandinavia where such services are less extensive and often organized in different ways. Yet, the theoretical argument of this paper is not necessarily restricted to market-type reforms of welfare services and the argument should be applicable to non-Scandinavian cases as well. When generalizing the argument, one factor that must taken into account is that in many European countries, Christian Democratic parties have played an important role in the creation of the welfare state (cf. van Kersbergen 1995).

This makes social democratic ownership of the welfare-state issue less clear affecting party political dynamics (cf. Green-Pedersen forthcoming(b)), but does make a focus on the social democratic parties unimportant (e.g. de

Vries and Yesilkagit 1999). The most promising cases for generalizing the argument of this paper are probably the Antipodes. In Australia and in particular New Zealand, a wave of NPM reforms was thus set in motion by labor governments (Schwartz 1994, Castles et al. 1996 and Denemark 1990).

27

References

Albæk, Erik, Lawrence Rose, Lars Strömberg & Krister Ståhlberg (eds.)

(1996). Nordic Local Government , Helsinki: The Association of Finnish

Local Authorties.

Anell, Anders (1996). "The Monopolistic Integrated Model and Health Care

Reform: The Sweidsh Experience", Health Policy, 37, 1, pp. 19-33.

Anell, Anders & Patrick Svarar (1995). "Ekonomiska styrformer i hälso- och sjukvärden: utvecklingslinjer och lärdomar för framtiden", pp. 35-54 in Den planerade marknaden , Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen.

Ant man, Peter (1994). "Vägen til systemskiftet - den offentlige sektorn", pp.

1966 in Rolf Å. Gustafsson (ed.), Köp och sälj, var god svälj?

, Stockholm:

Arbetsmiljöfonden.

Barlow, John, David Farnham, Sylvia Horton & F. F. Ridley (1996).

"Comparing Public Managers", pp. 3-25 in David Farnham, Sylvia Horton,

John Barlow & Annie Hondeghem (eds.), New Public Managers in Europe ,

London: Macmillan.

Bentzon, Karl-Henrik (1988). "Moderniseringsprogrammets historie", pp. 17-

35 in Karl-Henrik Bentzon (ed.),

Fra vækst til omstilling

, Copenhagen: Nyt

Fra Samfundsvidenskaberne.

Berg, Anders (2000). "När staten blev kapitalist - Marknadsanpassningen av de svenska affärsverken", Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift, 81, 1, pp. 56-

72.

Bertelsen, Christian (2000). Politikernes kontroldilemma , Copenhagen:

Akademisk Forlag.

Bertelsen, Christian (forthcoming). Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift .

Bille, Lars (1999). "Politisk kronik 2. halvår 1998", Økonomi og Politik, 72, 1, pp. 54-65.

Blom-

Hansen, Jens (1998). "Fuld behovsdækning!

Skandinavisk børnepasningspolitik mod år 2000", Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift, årg.

79, nr. 3, pp. 329-352.

BlomHansen, Jens (1998). "Sisyfos på arbejde: Ventetidsgarantier i de skandinaviske sygehusvæsener",

Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift,

årg. 79, nr. 4, pp. 359-389.

Blomqvist, Paula (2000). Ideas and Policy Convergence. Health Care Reform in the Netherlands and Sweden in the 1990s, paper prepared for the

Twelfth International Conference of Europeanists, March 30 - April 1,

Chicago.

28

Blomqvist, Paula & Bo Rothstein (2000).

Välfädsstatens nya ansikte.

Demokrati och marknadsreformer inom den offentliga sektorn , Stockholm:

Agora.

Borchorst, Anette (2000). "Den danske børnepasningsmodel - kontinuitet og forandring", Arbejderhistorie, 4, pp. 55-69.

Bor éus, Kristina (1997). "The Shift to the Right: Neo-liberalism in

Argumentation and Language in the Swedish Public Debate since 1969",

European Journal of Political Research, 31, pp. 257-286.

Budge, Ian & Dennis Farlie (1983). "Party Competition - Selective Emphasis or Direct Confrontation? An Alternative View with Data", pp. 267-305 in

Hans Daalder & Peter Mair (eds.), West European Party Systems.

Continuity & Change , London: Sage Publications.

BUPL (2000). En redegørelse om udlicitering af daginstitutioner ,

Copenhagen: BUPL.

Castles, Francis G., Rolf Gerritsen & Jack Vowles (eds.) (1996). The Great

Experiment. Labour parties and public policy transformation in Australia and New Zealand , Sidney: Allen & Unwin.

Christensen, Jørgen G. (1991).

Den usynlige stat , Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Christensen, Jørgen G. (1992). "Hierarchical and Contractual Approaches to

Budgetary Reforms", Journal of Theoretical Politics, 4, 1, pp. 67-91.

Christensen, Jørgen G. (2000). "Governance and Devolution in the Danish

School System", pp. 198-216 in Margaret A. Arnott & Charles D. Raab

(eds.), The Governance of Schooling. Comparative Studies of Devolved

Management , London and New York: Routledge/Falmer.

Christensen, Jørgen G. & Thomas Pallesen (2000). The Political Benefits of

Corporatization and Privatization, paper . Aarhus: Department of Political

Science, University of Aarhus.

Christensen, Jørgen G. & Thomas Pallesen (2001). "Institutions, Distributional

Concerns, and Public Sector Reforms", European Journal of Political

Research, 39, 2.

Christiansen, Peter M. (1998). "A Prescription Rejected: Market Solutions to

Problems of Public Sector Governance", Governance, 11, 3, pp. 273-295.

Christoffersen, Henrik & Martin Paldam (forthcoming). "Markets and

Municipalities. A Study of the Behaviour of the Danish Municipalities",

Public Choice .

Clark, David (2000). "Public Service Reform: A Comparative West European

Perspective", West European Politics, 23, 3, pp. 25-44.

Clayton, Richard & Jonas Pontusson (1998). "Welfare State Retrenchment

29

Revisited: Entitlements Cuts, Public Sector Restructuring, and Egalitarian

Trends in Advanced Capitalist Societies", World Politics, 51, 1, pp. 67-98.

Danmarks Statistik (various years and issues). Statistiske efterretninger:

Social Sikring og Retsvæsen , Copenhagen: Danmarks Statistik.

Danmarks Statistik (various years and issues). Statistiske efterretninger:

Uddannelse og kultur , Copenhagen: Danmarks Statistik. de Vries, Jouke & Kutsal Yesilkagit (1999). "Core Executives and Party

Policies: Privatization in the Netherlands", West European Politics, 22, 1, pp. 115-137.

Denemark, Davic (1990). "Social Democracy and the Politics of Crisis in New

Zealand, Britain and Sweden", pp. 270-289 in Martin Holland & Jonathan

Boston (eds.), The Fourth Labour Government , Auckland: Oxford

University Press.

Det Kommunale Kartel Organisationsafdelingen (1999). Udlicitering på

ældreområdet , Copenhagen: Det Kommunale Kartel. www.dkk.dk.

Diderichsen, Finn (1995). "Market Reforms in Health Care and Sustainability of the Welfare State: Lessons from Sweden", Health Policy, 32, 2, pp. 141-

153.

Dyremose, Henning (1999). "Privatisering - historien om en borgerlig holdningsændring", pp. 131-139 in Torben Rechendorff & Lars Kjølbye

(eds.),

P.S. Festskrift til Paul Schlüter

, Copenhagen: Aschehoug.

Esping-

Andersen, Gøsta (1990).

Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism ,

Cambridge: Polity.

EspingAndersen, Gøsta (1999). Social Foundations of Postindustrial

Economies , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Farnham, David, Sylvia Horton, John Barlow & Annie Hondeghem (eds.)

(1996). New Public Managers in Europe , London: Macmillan.

Feldt, Kjell-Oluf (1991). Alla dessa dagar , Stockholm: Norstedts.

Flynn, Norman & Franz Strehl (eds.) (1996). Public Sector Management in

Europe , London: Prentice Hall and Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Forssell, Anders (1999). Offentlig reformation i marknadsmodellernas spår,

SCORE's Working Paper Series 1999:5. Stockholm: Stockholms

Universitet.

Garpenby, Peter (1995). "Health Care Reform in Sweden in the 1990s: Local

Pluralism versus National Coordination", Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 20, 3, pp. 695-716.

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2000). How Politics Still Matters. Retrenchment

30

of old-age persions, unemployment benefits, and disability pensions/earlyretirement benefits in Denmark and in the Netherlands from 1982 to 1998 ,

Ph.D.dissertation, Århus: Department of Political Science, University of

Aarhus.

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (forthcoming(a)). "Welfare State Retrenchment in Denmark and the Netherlands, 1982-1998. The Role of Party

Competition and Party Consensus", Comparative Political Studies .

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (forthcoming(b)). "The Puzzle of Dutch Welfare

State Retrenchment: The Importance of Dutch Politics", West European

Politics .

Greve, Carsten (1997).

"Fra ideologi til pragmatisme? Træk af forvaltningspolitikken for privatisering i Danmark 1983-1996", pp. 35-63 in

Carsten Greve (ed.), Privatisering, selskabsdannelser og udlicitering ,

Århus: Systime.

Greve, Carsten (2000). "Exploring Contracts as Reinvented Institutions in the

Danish Public Sector", Public Administration, 78, 1, pp. 153-164.

Gustafsson, Lennart (1987). "Renewal of the Public Sector in Sweden",

Public Administration, 65, 2, pp. 179-191.

Håkansson, Anders (1997). "Nittiotalets förändringsvåg", pp. 57-70 in Anders

Håkansson (ed.),

Folket och Kommunerna. Systemskiftet som kom av sig ,

Stockholm: Stockholms Universitet, Statsvetenskapliga institutionen.

Hemerijck, Anton & Martin Schludi (2000). "Sequences of Policy Failures and

Effective Policy Responses", pp. 125-228 in Fritz W. Scharpf & Vivien A.

Schmidt (eds.), Welfare and Work in the Open Economy. Vol. 1. From

Vulnerability to Competitiveness , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hood, Christopher (1991). "A Public Management for All Seasons", Public

Administration, 69, 1, pp. 3-19.

Hood, Christopher (1996). "Exploring Variations in Public Management

Reforms of the 1990s", pp. 268-287 in Hans A. G. M. Bekke, James L.

Perry & Theo A. Toonen (eds.), Civil Service Systems in Comparative

Perspective , Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Huber, Evelyne & John D. Stephens (2000). "Partisan Governance, Women's

Employment and the Social Democratic Service State", American

Sociological Review, 65, 3, pp. 323-342.

Institut for Serviceudvikling (1999). Ud licitering på ældreområdet - Erfaringer fra Sverige og barrierer i Danmark , Odense: Institut for Serviceudvikling.

Jacoby, William G. (2000). "Issue Framing and Public Opinion on

Government Spending", American Journal of Political Science, 44, 4, pp.

750-767.

31

Kickert & Walter J.M. (ed.) (1997). Public Management and Administrative

Reforms in Western Europe , Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Kitschelt, Herbert (2001). "Partisan Competition and Welfare State

Retrenchment. When Do Politicians Choose Unpopular Policies?" in Paul

Pierson (ed.), The New Politics of the Welfare State , Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Klausen, Kurt K. (1999).

"Indikatorer på NPM's gradvise, men begrænsede gennemslag i Danmark", pp. 3249 in Kurt K. Klausen & Krister Ståhlberg

(eds.), New Public Management i Norden , Odense: Odense

Universitetsforlag.

Knudsen, Tim & Bo Rothstein (1994). "State Building in Scandinavia",

Comparative Politics, 26, 2, pp. 203-220.

KommunAktuellt Dirkekt - 16/9 1999 . Privat äldrevård klyver partierna . http://www.kommunaktuellt.com/arkiv/enkat/entreprenad.htm.

Kristensen, Ole P. (1987). Alliancer og konflikter i forbindelse med privatisering, paper presented at the FAFO seminar on privatization,

October 7-8, Oslo.

Kristensen, Ole P. (1988). The Politics of Privatization: The Case of Denmark, paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, April 5-10,

Remini.

Lane, Jan-Erik (1996). "Reform in the Nordic Countries", pp. 188-208 in Jan-

Erik Lane (ed.), Public Sector Reform , London: SAGE.

Lehto, Juhani Moss Nina & Tina Rostgaard (1999). "Universal public social care and health services?", pp. 104-132 in Mikko Kautto, Matti Heikkila,

Bjørn Hvinden, Stafan Marklund & Niels Ploug (eds.),

Nordic Social Policy ,

London: Routledge.

Lidström, Anders (1999). "Local School Choice Policies in Sweden",

Scandinavian Political Studies, 22, 2, pp. 137-156.

Lidström, Anders & Christine Hudson (1995). Skola i förändring.

Decentralisering och lokal varition

, Stockholm: Nerenius & Santérus

Förlag.

Lindbom, Anders (1995). Medborg arskapet i välfärdsstaten.

Foräldrainflytande i skandinavisk grundskola , Stockholm: Almqvist &

Wiksell International.

Lindbom, Anders (1998). "Institutional Legacies and the Role of Citizens in the Scandinavian Welfare State", Scandinavian Political Studies, 21, 2, pp.

109-128.

Loughlin, John & Guy B. Peters (1997). "State Traditions, Administrative

Reforms and Regionalization", pp. 41-62 in Michael Keating & John

32

Loughlin (eds.), The Political Economy of Regionalism , London: Frank

Cass.

Montin, Stig (1992). "Privatiseringsprocesseri kommunerna - teoretiska utgångspunkter och empiriska exempel", Statsvetenskaplig Tidsskrift, 95,

1, pp. 31-57.

Montin, Stig (1997). "New Public Management på svenska",

Politica, 29, 3, pp. 262-278.

Montin, Stig & Ingemar Elander (1995). "Citizenship, Consumerism and Local

Government in Sweden", Scandinavian Political Studies, 18, 1, pp. 25-51.

Nannestad, Peter & Christoffer Green-Pedersen (forthcoming). "Keep the

Bumblebee Flying: Economic Policy in the Welfare State of Denmark,

19731999" in Erik Albæk et al. (eds.), Managing the Danish Welfare State under Pressure: Towards a Theory of the Dilemmas of the Welfare State ,

Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

OECD (1993). Managing with Market-Type Mechanisms , Paris:

OECD/PUMA.

OECD (1999). Financial Markets Trends 72 , Paris: OECD.

Olsen, Johan P. & B. Guy Peters (1996). "Learning from Experience?", pp. 1-

35 in Johan P. Olsen & B. Guy Peters (eds.), Lessons from Experience ,

Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

Pallesen, Thomas (1997). Health Care Reforms in Britain and Denmark: The

Politics of Economic Success and Failure , Århus: Politica.

Pallesen, Thomas & Lars D. Pedersen (forthcoming). "Health care in

Denmark. Adapting to cost containment in the 1980s" in Erik Albæk, Leslie

C. Eliaso n, Asbjørn S. Nørgaard & Herman Schwartz (eds.),

Managing the

Danish Welfare State under Pressure: Towards a Theory of the Dilemmas of the Welfare State , Århus: Aarhus University Press.

Peters, B. Guy (1997). "Policy Transfers Between Governments: The Case of

Administrative Reforms", West European Politics, 20, 4, pp. 71-88.

Pierre, Jon (1993). "Legitimacy, Institutional Change, and the Politics of

Public Administration in Sweden", International Political Science Review,

14, 4, pp. 387-401.

Pierson, Paul (1994). Dismantling the Welfare State. Reagan, Thatcher, and the Politics of Retrenchment , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pierson, Paul (1996). "The New Politics of the Welfare State", World Politics,

48, 2, pp. 143-179.

Pollitt, Christopher & Geert Bouckaert (2000). Public Management Reform. A

Comparative Analysis , Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press.

33

Pollitt, Christopher & Hilkka Summa (1997). "Trajectories of Reform: Public

Management Change in Four Countries", Public Money & Management,

17, 1, pp. 7-18.

Premfors, Rune (1991). "The "Swedish Model" and Public Sector Reform",

West European Politics, 14, 1, pp. 83-95.

Premfors, Rune (1998). "Reshaping the Democratic State: Swedish

Experience in a Comparative Perspective", Public Administration, 76, 2, pp.

142-159.

Rehnberg, Claus (1997). "Sweden", pp. 64-86 in Chris Ham (ed.), Health

Care Reform Learning from International Experience , Buckungham: Open

University Press.

Rhodes, Rod A. W. (1999). "Traditions and Public Sector Reform: Comparing

Britain and Denmark", Scandinavian Political Studies, 22, 4, pp. 341-370.

Riker, William (1986). The Art of Political Manipulation , New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Ross, Fiona (2000a). "Beyond Left and Right: The New Partisan Politics of

Welfare", Governance, 13, 2, pp. 155-183.

Ross, Fiona (2000b). "Interest and Choice in the Not Quite so New Politics of

Welfare", West European Politics, 23, 2, pp. 11-34.

Rothstein, Bo (1993). "The Crisis of the Swedish Social Democrats and the

Future of the Universal Welfare State", Governance, 6, 4, pp. 492-517.

Sahlin-Andersson, Kerstin (1999). "I mötet mellam reform och praktik", pp.

293-311 in Eva Z. Bentsen et al. (eds.), Når styringsambitioner møder praksis , Copenhagen: Handelshøjskolens Forlag.

Saltman, Richard B. & Josep Figueras (1998). "Analyzing the Evidence on

European Health Care Reforms", Health Affairs, March/April, pp. 85-108.

Scharpf, Fritz W. & Vivien A. Schmidt (eds.) (2000). Welfare and Work in the

Open Economy , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schattschneider, Elmer E. (1960). The Semi-Sovereign People. A Realist's

Guide to Democracy in America , New York: Holt.

Schüllerqvist, Ulf (1995). "Förskjutningen av svensk skolpolitisk debatt under det senaste decenniet", pp. 44-106 in Tomas Englund (ed.),

Utbildningspolitiskt systemskifte?

, Stockholm: HLS Forlag.

Schwartz, Herman (1994). "Small States in Big Trouble. State Reorganization in Australia, Denmark, New Zealand, and Sweden in the 1980s", World

Politics, 46, 4, pp. 527-555.

Skolverket (2000a). Beskrivande data om barnomsorg och skola 2000.

34

Rapport 192 , Stockholm: Skolverket.

Skolverket (2000b). Barnomsorg och skola i siffror 2000: Del 2 - Barn, personel, elever och lärare

, Stockholm: Skolverket.

Socialstyrelsen (1999). Konkurrensutsättning och entreprenader inom

äldreomsorgen , Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen.

SOU 2000:3. Delbokslut: Välfärd under 1990-talet - en sammenfatning ,

Stockholm.

Stone, Deborah (1997). Policy Paradox. The Art of Political Decision Making ,

New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company.

Svensson, Helene & Sara Nordling (1995). "Effekter av nya ekonomiska styrformer - en litteraturöversikt", pp. 55-77 in Den planerade marknaden ,

Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen.

Svensson, Torsten (2000). The Marketization of the Swedish Model, paper prepared for the Conference on Institutional Analysis and Contemporary

Challenges of Modern Welfare States, May 25-27, Gothenburg.

Szebehely, Marta (2000). "Âldreomsorg i förandring - knappare resurser och nya organisationsformer", pp. 171-223 in SOU 2000:39 , Stockholm.

Thomse n, Søren R. (1998). "Impact of National Politics on Local Elections in

Scandinavia", Scandinavian Political Studies, 21, 4, pp. 325-345. van Kersbergen, Kees (1995). Social Capitalism. A Study of Christian

Democracy and the Welfare State , London: Routledge.

Vrangbæk, Karsten (1999). "New Public Management i sygehusfeltet - udformning og konsekvenser" in Eva Z. Bentsen et al. (eds.),

Når styringsambitioner møder praksis , Copenhagen: Handelshøjskolens

Forlag.

Vrangbæk, Karsten (2000). "Forandringer i sygehussektoren som følge af frit sygehusvalg", pp. 117-148 in Marianne Antonsen & Torben Beck

Jørgensen (eds.),

Forandringer i teori og praksis

, Copenhagen: DJØFs

Forlag.

Weaver, R. Kent (1986). "The Politics of Blame Avoidance", Journal of Public

Policy, 6, 4, pp. 371-398.

Wright, Vincent (1994). "Reshaping the State: The Implications for Public

Administration", West European Politics, 17, 3, pp. 102-137.

Yesilkagit, Kutsal & Jouke de Vries (forthcoming). "Core Executives,

Institutions and Public Sector Reform in New Zealand and the

Netherlands", Public Administration .

35

36