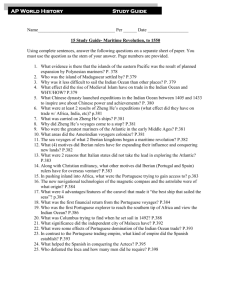

S Deckla

advertisement