The Prospect for Industrial Sprawl in Rural NS – Don Rushton

advertisement

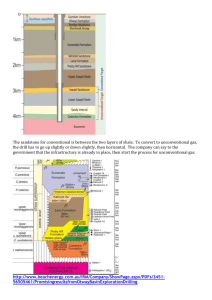

1 The Prospects for Industrial Sprawl in Rural Nova Scotia by Don Rushton Amherst Head 16 March 2014 2 The central argument of this submission is that unconventional gas development in Nova Scotia would result in levels of industrialization unacceptable to the individuals and communities immediately affected. As it is, rural Nova Scotia is hardly pristine and there can be few residents without at least intermittent industrial farming or forestry close at hand. Also, industries, such as the salt mine in Pugwash, have an effect beyond their immediate location because of the amount of heavy truck traffic they create. Yet, no other resource industry demands the spatial proliferation of infrastructure required by unconventional gas drilling. There is, of course, a great deal of public anxiety generated by the possibility that Nova Scotia might allow industry to exploit it's shale formations. Indeed, the mandate of the present commission is to examine the science and determine, in a sense, if the general anxiety is rational or should be contradicted and overruled. The assumption is that science can be the arbiter. A recent article in The New Yorker, however, points to difficulties with this assumption. (1) The author writes, "Fussy critiques of scientific experiments have become integral to what is known as the 'sound science' campaign, an effort by interest groups and industry to slow the pace of regulation." She adds, "David Michaels, the Assistant Secretary of Labor for Occupational Safety and Health, wrote, in his book 'Doubt is Their Product' (2008) that companies have developed sophisticated strategies for 'manufacturing and magnifying uncertainty'. " She continues to quote Michaels. "In field after field, year after year, conclusions that might support regulation are always disputed. Animal data are deemed not relevant, human data not representative, and exposure data not reliable." Not surprising then, that when the 3 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of the United States published a draft paper on pollution that was obviously associated with fracking in Pavillion, Wyoming, "The study drew heated criticism over its methodology and awaited a peer review that promised to settle the dispute." (2) Subsequently the EPA gave up its investigation and passed the folder to "the state of Wyoming, whose research will be funded by EnCana, the very drilling company whose wells may have caused the contamination." (3) Even as it stood, as opposed to an overall study of the problems associated with unconventional gas drilling, the scope of the Pavillion study was limited. In a submission to the Energy and Environment Subcommittee (4) (a congressional committee in the U.S.) in Feb 2012, Dr. Bernard D. Goldstein of the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh wrote, "a focus that is solely on the issue presented by the Pavillion study seems like a subterfuge designed to avoid answering their (the public's) questions about the overall impact of unconventional shale gas drilling on their environment and on their health." Dr. Goldstein went on to emphasize "the current lack of almost any support for research directly related to the health effects of unconventional gas drilling." A recent article in the Chronicle Herald perpetuates one of the most common myths regarding fracking. It states, "But hydraulic fracturing, which was invented in 1947, commercialized in 1949, and has been used over 2.5 million times worldwide for oil and gas development, is not new. So the risks are well understood and are generally no greater than those posed by any other type of oil and gas development activity." (5) In a lecture in December of 2010 at the Luzerne County Community College in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania, Dr. Anthony Ingraffea of Cornell University 4 explains why such statements are misleading. Most of what follows is taken from that lecture, often verbatim. (6) Unconventional gas well drilling today uses four relatively new technologies. These are: directional drilling, high volumes of fracking fluid, slick water and multi-well pads. Directional drilling allows for long laterals (the longest in Pennsylvania at the time was about a mile and a half) through the layer of shale, intersecting the natural fractures. Because the laterals are long and intersect many fractures, much higher volumes of fracking fluid are required (Whereas 50,000 gallons might have been used to frack a vertical well in the past, current wells can use 5 million gallons or more.) To counteract friction, polymers and/or surfactants are added to the water to create slickwater (this was first done in 1996). And finally, multi-well pads (first done in 2007) are used to maximize access to the shale. So, one can safely say, modern fracking is less than 20 years old and the long term effects are simply unknown. Increased well density (wells/sq. mile) means greater industrial development over larger areas and greater risk. While the higher volumes of fracking fluid mean higher volumes of waste water containing fracking chemicals, heavy metals, naturally occurring radioactive material (NORMs) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). A pro industry brochure prepared for Quebec's Bureau d'audiences publiques sur l'environement (7) states a multi-well pad site covers 2 to 5 acres and that 4 to 8 wells per site are typical, while 12 to 16 wells per site are possible. Drilling 24 hours/day and 7 days/week, it takes 90 to 120 days to go 0.8 to 3 kilometers below the surface. 3 to 5 million gallons of fluid are required for fracking. The compressors used to create the pressure required for fracking may use a 40,000 Horsepower diesel motor, generating noise and exhaust pollution. And if a large tanker truck can carry 11,600 gallons (U.S.) and 5 a well uses 4 million gallons, 345 truckloads are required, as well as many more truckloads to transport proppant (usually sand). Rural neighbourhoods will be turned into industrial parks: huge motors running day and night, enormous truck traffic, gas flares, access roads, pipelines and large tanks or waste storage ponds and drilling pads. We live in a fossil fuel civilization. Indeed, it is often claimed that the benefits of oil and gas exploitation outweigh its environmental and health risks. At the same time, we know fossil fuels are a limited resource and that the modern industrial world has caused global warming that will likely lead us from intermittent to general catastrophe. In a submission prepared for the Council of Canadians (8) and submitted to the Ontario Energy Board (June, 2013), Dr Ingraffea reiterates the findings of what is known as the Cornell Study, which he co-authored. He clearly states, "The footprint for shale gas is greater than for conventional gas or oil and for coal used for electricity generation...". He also notes,"...carbon trading markets at present undervalue the greenhouse warming consequences of methane." Methane is promoted as a bridging fuel by government and industry, but overall, its carbon footprint is greater and the cost of reducing fugitive emissions of methane and significantly reducing the environmental and health risks of unconventional gas drilling will makes its cost prohibitive. It might be argued that the capital willing to invest in unconventional gas would be better spent on alternative energies, but generally speaking, capital seeks dividends and not the common good. And we can only speculate about the sort of political leadership required to fight the continual growth of dysfunctional industrial infrastructure. The final part of Dr. Ingraffea's December 2010 lecture was devoted to the risks associated with unconventional gas drilling. While much of the public anxiety about fracking is related to well water contamination by 6 fracking fluids and methane, Dr. Ingraffea explains the low probabability, but not impossibility, of contamination from deep underground. The greater risk is from the well itself and its cement lining. He also points out that the distinction between flowback and 'produced water' is arbitrary. Over the life of a well almost all of what is put down the well will come back up and that treating produced water as no more than brine is to ignore the possibility of contaminants such as NORMs. However, the greatest risks may be above ground where huge amounts of chemicals and contaminated fluids must be stored and transported. Using a chart produced by Dr. Terry Engelder of Penn State University and an advocate for the exploitation of shale gas in Pennsylvania, Dr. Ingraffea, in his Nanticoke lecture, describes a rate of one serious environmental accident for every 150 wells drilled in the Marcellus between January 2008 and August 2010 (for some reason this excluded Dimock Township where there was serious contamination of well water). Dr. Ingraffea describes this as 98.5% safe and uses this to illustrate the deceptiveness of percentages when dealing with large numbers. And, while Dr. Engelder describes this as a good record, although aiming to reduce the incidence, Dr. Ingraffea describes it as a poor record. Who decides what is acceptable? For example, what is the risk from accidental spills when large amounts of fracking fluids are being transported? Surely the communities most directly affected by this industrial development should be able to accept or reject it. Finally, to make an informed decision, individuals must have a clear picture of how well pads would be distributed. Dr. Ingraffea displays a 'spacing unit' proposed by Chesapeake Energy in New York State that covers 640 acres. There are 640 acres in a square mile, while the rectangular spacing unit is approximately 3.5 times longer than it is wide. Ten wells are proposed from a central pad. The spacing unit is 7 rectangular as the well laterals, in this instance, run either north northwest or south southeast. If the spacing units are contiguous, the well pads are obviously much closer together moving west southwest or east northeast, than in the direction of the laterals. The gas in our provincial shale formations should be left where it is. No other industry threatens the disruption of rural areas like unconventional gas. It is only a fix in the sense that the word is used of drug addiction. It will only worsen our dysfunction while we avoid living ecologically. 1) The New Yorker, 10 February 2014, Annals of Science, A Valuable Reputation by Rachael Aviv 2) www.propublica.org/article/epas-abandoned-wyoming-fracking-studyone-retreat-of-many 3) ibid 4) www.chec.pitt.edu/documents/testimonies/02-0112_GoldsteinCEE.pdf 5) The Chronicle Herald, Misinformation poisons the hydro-fracking well by Richard Gagne, pg A13, 12 February 2014. 6) http://ecowatch.com/2013/01/02/industry-insider-to-frackingopponent/ 7) www.bape.gouv.qc.ca/sections/mandates/Gaz_de_schiste/.../DB61.pdf 8) www.canadians.org/sites/default/files.../OEB%20Ingraffea.pdf Dr. Ingraffea's letter includes the Cornell Study as an appendix.