Populations projections - The Graduate Institute, Geneva

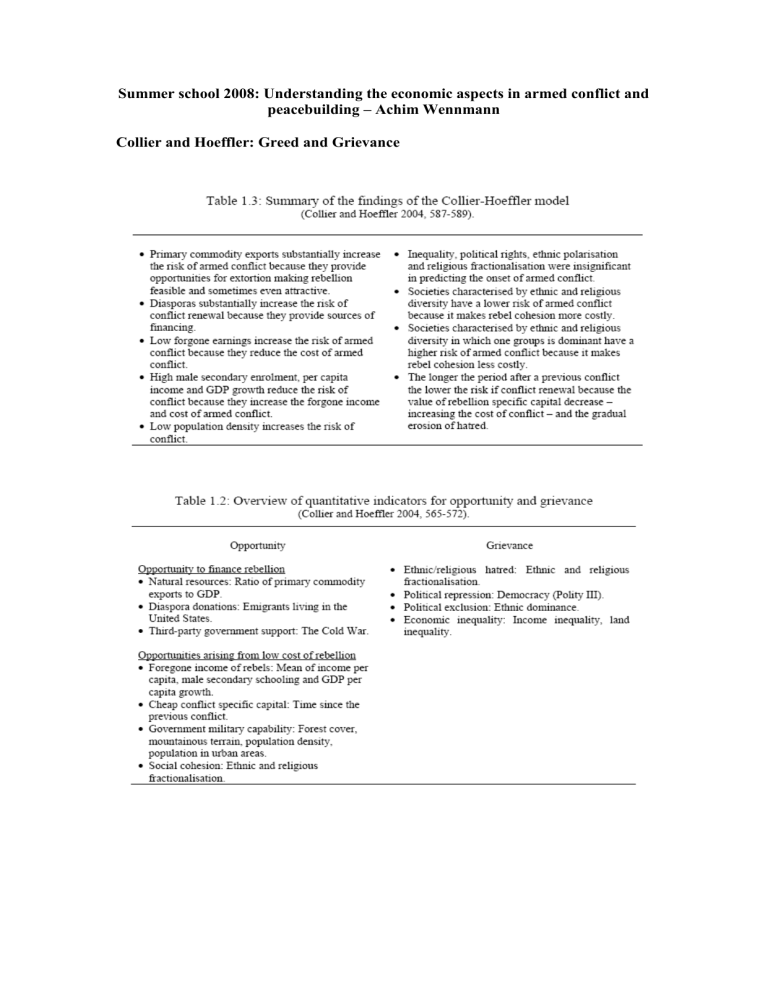

Summer school 2008: Understanding the economic aspects in armed conflict and peacebuilding – Achim Wennmann

Collier and Hoeffler: Greed and Grievance

2

Conflict financing

Alternative conceptualisations of conflict economies and their evolution

(from Wennmann 2007, 91-92)

In his seminal study Wages of Crime: Black Markets, Illegal Finance, and the Underworld Economy ,

R. Thomas Naylor presents a model of insurgencies based on the interaction of the type of conflict economy and the military strategy of insurgents interact. He distinguishes three stages:

(1) Predation-Contention : The conflict economy is predatory and the military strategy is based on contention with government forces. Insurgents operate in areas still formally in control of the state. In order to destabilise the state and raise funds, insurgents conduct hit and run attacks such as killings, kidnappings, burglaries, or bank robberies. Expenditure requirement at this stage are small as the rebel group itself is small.

(2) Parasite-Expansion : Insurgent activities mature and its funding become increasingly parasitical.

Its operations become rooted in a particular geographic area in which insurgents expand their control. The nature of violence shifts from hit and run attacks against political symbols to low intensity warfare and economic strategies of conflict to disrupt economic activity and weaken the government. As the formal economy declines, the guerrilla becomes increasingly involved in managing a parallel economy. In this way, the government looses fiscal revenues and is further politically discredited while the guerrilla is strengthened through the profits of the parallel economy.

(3) Extraction-Territorial Control : Insurgents establish control over an area from which the state is excluded. In this area, the guerrilla becomes the de-facto government including the provision of social services and means of arbitration and maintains a taxation system with which it generates fund for its activities.

Guerrilla groups to which this dynamism applied included the Shining Path in Peru, the National

People’s Army in the Philippines, the Bougainville rebels in Papua New Guinea, the Khmer Rouge in

Cambodia, the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka, UNITA in Angola, the Maoist rebels in Nepal and the

FARC in Colombia (Naylor 2002, 45-47, 53-54).

Naylor’s model on insurgency economies has important parallels to Tilly’s model on state making. Similarly to Tilly, the model contends that as control over territory and population is established, institutions are created to enhance extraction. The difference is that external recognition is not provided despite the territory and institutions created by an insurgent group may be similar to state institutions. If just looking at the empirical aspects of statehood, the distinction between the conflict financing of states and insurgents may become blurred.

Thus, Naylor’s model could be expanded to include a fourth category: the de facto state. De facto states exist

“where there is an organized political leadership which has risen to power through some degree of indigenous capability; receives popular support; and has achieved sufficient capacity to provide governmental services to a population in a specific territorial area, over which effective control is maintained for a significant period of time. The de facto state views itself as capable of entering into relations with other states and it seeks full constitutional independence and widespread international recognition as a sovereign state. It is, however, unable to achieve any degree of substantive recognition and therefore remains illegitimate in the eyes of international society” (Pegg 1998, 26).

Understanding de facto states requires a differentiation between empirical and juridical sovereignty.

Empirical sovereignty is associated to the principles of statehood identified in the 1933 Montevideo

Convention on Rights and Duties of States: a permanent population, a defined territory, a government and the capacity to enter into relations with other state (see Malanczuk 1997, 75-81). While de facto states may have empirical aspects of sovereignty, they lack juridical sovereignty associated with international recognition as their territory is located in an area part of an already recognised state.

Conflict financing

3

Mobilisation cost (Wennmann 2007, 116-118)

4

Estimating the cost of armed conflict (Wennmann 2008, 138)

5

6

![De facto property regime - frequently asked questions [DOC 178KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007901646_2-235cfad4a7cd61ae5700fe71169e2528-300x300.png)