Governing Sexual Abuse and Exploitation by Humanitarian Aid

advertisement

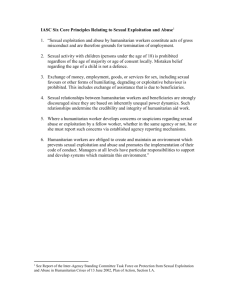

Governing Sexual Abuse and Exploitation by Humanitarian Workers through Codes of Conduct By: Stephanie Matti (IHEID) Introduction At a conference on preventing sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) in the humanitarian sector, one humanitarian practitioner made the point that humanitarian organisations should not be “judged on whether they have instances of sexual exploitation and abuse”, because it can happen in every organisation, but on the “mechanisms that they have in place to deal with it when it happens” (2011). Another participant argued that if codes of conducti, which have emerged as a key PSEA mechanism since the issue because widely publicised in 2001, are to tackle sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA), they must reaffirm humanitarian values. These comments raise a number of questions. How do codes of conduct change SEA behaviour? Do different codes draw on different governance techniques? What are humanitarian values and how does an appeal to them influence SEA behaviour? And, more fundamentally, what organisations have codes of conduct and do they cover PSEA? While there is a substantial literature on humanitarian codes of conduct most of this has focused on the UN response to SEA or on broad humanitarian codes which do not cover SEA specifically. There has been no systematic study of PSEA codes of conduct in the humanitarian sector. This paper aims to fill this gap in the literature. The aims of this paper are threefold. It firstly aims to analyse how widespread codes of conduct are in the humanitarian sector by surveying online references to codes of conduct made by 100 nongovernmental humanitarian organisations. Second, it aims to analyse how PSEA has been incorporated into codes of conduct in the humanitarian sector. These first two sections establish who and what is being governed by PSEA codes of conduct. Finally this paper will draw on discourse analysis to address the question: how do codes of conduct govern the sexual exploitation and abuse of intended beneficiaries by humanitarian workers? This paper is based on an eclectic theoretical framework informed by Foucault’s analytics of government, Kratochwil’s examination of social institutions, norms and values, and speech act theory. By drawing on a combination of these theories, this paper aims to establish a holistic picture of how PSEA codes of conduct function as a social institution, what the rationalities underpin them and how they affect social practice. Theoretical Framework Foucault’s analytics of government, Kratochwil’s examination of norms and rules and speech act theory all examine the role of language and norms in governance. Despite considerable epistemological and methodological differences, all three are founded on the ontological premise that social reality is based on the inter-subjective understanding of social phenomena. Each theory contributes a different aspect to understanding how PSEA codes of conduct shape social practice: Foucault’s analytics of government investigates the rationalities underpinning governance through which ‘truths’ are created; speech act theory examines how social institutions generate the deontic power through illocutionary force; and Kratochwil examines the role of norms and values in judging and justifying social practice. By combining aspects of each of these theories, this paper aims to establish a theoretical toolkit through which it is possible to gain a holistic understanding of how PSEA codes of conduct govern the SEA behaviour of humanitarian workers. Foucault’s primary contribution is his interrogation of government. Government refers to systematized, regulated and reflected modes of power which is more than the spontaneous exercise of power over others. This government follows a specific rationality or form of reasoning which defines the adequate means to achieve it (Lemke 2000, p.5). In this way the traditional state-centric 0 view of government is expanded to include any “regulation of conduct by the more or less rational application of the appropriate technical means” (Hindess 1996, p. 106). Governance is not a topdown process whereby the government forces people to do what it wants. Rather, government is a balance between coercive techniques and “processes through which the self is constructed or modified by himself” (Foucault 1993, p. 203-4). The primary goal of government to create a social reality that it suggests already exists (Lemke 2000, p.13). In analysing governance, the key objective is not to establish whether governance is followed, but rather to discover the rationalities that are employed (Foucault 1981, p. 226). In assessing different forms of rationality the focus on how they “inscribe themselves in practices or systems of practices, and what role they play within them, because… ‘practices’ don’t exist without a certain regime of rationality” (Foucault 1991b, p.79). Rationality is not a neutral knowledge that attempts to re-create an external reality. Government itself creates a discursive field in which the exercising power determines what is considered rational. The analytics of governance approach suggests it is important to examine whether this rationality is an adequate representation of society, but also “how it functions as a ‘politics of truth’, producing new forms of knowledge, inventing new notions and concepts that contribute to the ‘government’ of new domains of regulation and intervention.” (Lemke 2000, p.7) Foucault argues that advanced liberal democracies are characterised by a form of ‘neo-liberal governmentality’ in which power is decentralised with citizens playing an active role in their own governance. An important aspect of this is the increased role played by civil society actors including NGOs in government. The neo-liberal governance strategy is to render individuals responsible for their own actions thereby transforming collective or social problems such as criminality, poverty and illness into a problem of self-care (Foucault 1991a, p.103). Speech act theory, by contrast, examines how social institutions shape social practice. A social institution is a structure or mechanism of social order which governs the behaviour of a set of individuals through rule-bound practices. These social institutions are maintained through the continued widespread trust in a general system of expectations guaranteed by the intersubjective understanding of the rules. This must be based on a general belief in the reasonableness of these rules (Hall 2010, p.70). The more diverse a group, the more the intersubjective commitment to norms is likely to be challenged (Kessler et al 2010, p.2). According to Searle, social institutions are able to affect social practice because they create a special kind of power which obliges people to act in a manner that is not driven by desire. This power, which Searle terms deontic power, is marked by terms such as rights, duties, obligations, authorisations, permissions, empowerments, requirements and certifications. It is the force of this deontic power which causes people to change their behaviour (Searle 2005, p.10). Speech act theory provides important tools for understanding how deontic power is generated. Speech act theory differentiates between three parts of speech: the locutionary dimension of speech (saying something), the illocutionary force of speech (doing something by saying something, for example making a promise) and the perlocutionary effects of speech (the impact that a statement has on the listener). The concept of illocutionary force is central to speech act theory: that by expression alone, certain utterances themselves represent an act. The deontic power of certain utterances is generated through the illocutionary force of speech acts (Buzan et al 1998, p.17). A promise is an example of a particularly salient rule-bound social institution in which deontic power is generated through illocutionary force. Promising is governed by relatively simple intersubjective practice-type rules. One only has to use the words “I promise” to invoke the social institution of promising. The very utterance of the words “I promise” creates certain duties and 1 responsibilities for both the promiser and the receiver of the promise. Contracts, by comparison, require more elaborate rules and involve mutual obligations (Kratochwil 1989a, p.91). The deontic power of promises stems from the illocutionary force generated by the selfrepresentation of the speaker as a moral agent. In making a promise the promiser is essentially saying “I am a moral agent and you can rely on me to make good on my promise”. In order to retain this claim to social and moral agency, the promiser must undertake what s/he has committed to (Kessler 2010, p.11). If the promiser fails to make good on their promise, they surrender the moral agency required to make promises. Promises do not work as a social institution because of threatened sanctions or because they are compulsory, but rather due to the perceived duty of the promiser to make good on their promise (Hall 2010, p.62). A promise also has important perlocutionary effects including the social ‘obligation’ of the receiver to give credence to the promise, even if s/he doubts the promiser’s sincerity (Kessler 2010, p.11). The illocutionary force of the promise is such that to deny the sincerity of the promise is to deny the promiser the status of a moral agent. (Kratochwil 1989a, p.147) In other words, the illocutionary force of the self-representation of the speaker as a moral agent makes a promise impossible for the receiver to dismiss which, in turn, imposes a duty on the promiser to make good on what they have promised or risk their reputation as a moral agent. When someone breaks a promise the specific instance and reasons for the violation must be judged to determine whether the violation was justified. Norms and values provide guidance as to the validity of the reasons given. When a violation is shown to have occurred due a structural feature of the normative order it may be pardoned and the illocutionary force of the speech act disbanded. Such a situation might be destructive for specific social relationships but is unlikely to be destructive to the promiser’s wider moral agency. A violation that occurs due to rational deliberation or the calculation of utility, by contrast, will not be pardoned. In this way norms help us to uncover the reasons behind certain actions and are also a tool for assessing praise and blame (Hall 2010, p.67). Social institutions, and the norms and values which underpin them, are generally valid even if they fail to guide behaviour in specific cases (Kratochwil 1984, p.705). This frustrates any attempt to test the effects of a rule quantitatively. That said, social institutions are not static, whether a rule is followed or not does change the rule in its content and force. If a violation undermines the continued widespread trust in a general system of expectations, that is, if the rules are no longer intersubjectively understood, then a violation may undermine the social institution. All three of theories illuminate interconnected yet distinct aspects of how social institutions shape social practice. They all emphasise that the proper focus of such an investigation is the discourse, not the mental states and processes or observable behaviour. By combining these different constructivist theories eclectically this section has established a theoretical tool-kit to examine how PSEA codes shape social practice. The Problematisation of SEA This section establishes the context of SEA in the humanitarian sector. It aims to trace the process by which SEA has been problematised in the sector and how codes of conduct have emerged as a form of PSEA governance. The humanitarian sector is composed of a complex mosaic of different actors including major actors representing the United Nations, governments and government-run organisations, international nongovernmental organisations, affected governments, insurgent groups and local grass-root NGOs (Stephenson 2005, p.3). Humanitarian organisations and the people that work for them come from 2 broad spectrum of cultures, religions and professional backgrounds. Humanitarian response also involves a huge range of skills and diverse body of knowledge with humanitarian workers coming from professional backgrounds including engineering, medicine, law and political science (Walker 2004, p.7). These humanitarian workers and organisations deliver humanitarian relief in challenging environments in the wake of natural disasters or conflict. Recipient countries typically have “high levels of poverty, collapsed economies, weak judicial systems, corrupt and ineffective law enforcement agencies, weak or non-existent rule of law.” (Ndulo 2009, p.130) Humanitarian relief is generally under-funded. As a result, deciding who receives aid presents “field-level staff and local authorities and elites with considerable power, and considerable opportunity to abuse it.”(Willitts-King and Harvey 2005, p.33) A growing literature shows that many intended beneficiaries enter into sexual relations with humanitarian workers as a survival mechanism amid insufficient food rations and extreme poverty (Lalor 2004, p.22). In 2001 a widely publicised report pointed to high levels of SEA by humanitarian workers and UN forces of intended beneficiaries in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone (UNHCR and Save the Children UK, 2001). This prompted an investigation by the UN Office for Internal Oversight Services which found that the problem was real and widespread (Ndulo 2009, p.141). This sexual abuse and exploitation includes forced sex, child prostitution and child pornography, in addition to the exchange of sex or sexual acts for protection, food and non-food items, and relationships based on highly unequal power relations (Morris 2010, p.189). People of all ages and genders have been the ‘victim’ of SEA. However, girls and women are disproportionately represented among the ‘victims’. While this paper acknowledges the gendered dimension of SEA in the humanitarian sector, this paper aims to avoid reinforcing the cultural silencing of homosexual SEA by using the gender-neutral terms ‘intended beneficiaries’ to denote the people who organisations aim to assist, and ‘affected populations’ to denote the local population affected by a humanitarian crisis more broadly. The prosecution of SEA by humanitarian aid workers is problematic. In theory, there are three legal avenues for prosecution: the host country; the home country; and the International Criminal Court (ICC). However, all three legal options are limited in their applicability. Local prosecution is difficult due to local legal systems that are generally either in transition or dysfunctional (Harrington 2005, p.19). Meanwhile, the home countries of many humanitarian workers have not enacted laws that apply to crimes committed in a foreign State (Odello 2010). When such laws do exist, there are still considerable logistical difficulties in obtaining evidence and witness testimonies (Kihunah 2007, p.1; Ruden and Utas 2009, p.3). Finally, to be prosecuted through the ICC the crime must be part of a larger organised plan to harm the population as a whole, which is generally not the case in the humanitarian sector (Harrington 2005, p.22). All three legal options are extremely limited their capacity to act as a forum through which SEA acts by humanitarian workers can be persecuted. Given the dearth of legal options, codes of conduct represent an important mechanism for governing the behaviour of humanitarian workers. Codes of conduct are sets of principles which establish a minimum standard or ‘bottom-line’. While the content of humanitarian codes varies, they generally establish similar principles and ethics of development, and provide guidelines for not-for-profit management (Ebrahim 2003, p.820). These codes are seen as a standard against which the performance of an organisation may be measured and a tool through which organisations can be held to account by intended beneficiaries, members, volunteers, staff, partners and affiliates, donors and funders, and governments, as well as the general public (Hilhorst 2002, p.203). This paper is concerned with the mechanisms through which PSEA codes function rather than how they have been rolled-out and to what effect in practice. Although the two cannot be totally divorced, this paper does not examine in depth the dissemination, monitoring and enforcement of the codes of 3 conduct. Codes of conduct have long been used by humanitarian organisations to guide and govern the conduct of staff. For example, the most commonly cited code: the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in Disaster Relief, was established in 1994. However, it was not until 2001, following the UN report and subsequent investigation, that SEA widely problematised and seen as an issue requiring governance within the sector. The findings of these reports prompted the UN and the humanitarian sector more broadly to examine how they might better govern the behaviour of their staff. The UN adopted the Secretary General's Bulletin, Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (ST/SGB/2003/13) (The Bulletin hereafter) which acts as a PSEA code of conduct for all UN staff. The Bulletin defines sexual exploitation as “any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust for sexual purposes” and sexual abuse as “any actual or threatened physical intrusion of a sexual nature, whether by force of under unequal or coercive conditions.” (2003) Under The Bulletin, acts of SEA constitute “serious misconduct and are therefore grounds for disciplinary measures, including summary dismissal.” It also prohibits all sexual activity with children (under 18 years of age) regardless of consent, the age of consent in the host state or mistaken belief of age. All prostitution is prohibited, while relationships between peacekeeping personnel and beneficiaries are “strongly discouraged”. The UN investigation that led to The Bulletin recommended that all humanitarian organisations adopt codes of conduct that include, at a minimum, the core principles outlined in The Bulletin. By contrast, international, and to a lesser extent national, humanitarian NGOs have adopted a range of different PSEA measures. These include: addressing the root causes of gender based violence including poverty, inequality and demand for SEA (Spencer 2005, p.173); establishing and implementing PSEA codes of conduct; and working to minimise the recurrence of SEA through stricter vetting and monitoring processes (Morris 2010, p.199). PSEA codes have been promoted as a key mechanism for preventing SEA in the humanitarian sector by the UN and a range of accountability partnership organisations.ii The establishment of PSEA codes of conduct is viewed as being particularly important sector due to the short time-frame and emergency nature of humanitarian response. The adoption of PSEA codes has been largely driven by public scandal. The International Rescue Committee's SEA training module states that “public scandal is benefiting those most vulnerable to sexual exploitation... as many organisations that had not previously worked on gender based violence issues, are now motivated to do so.”(International Rescue Committee 2003, p.2) Such scandals have moved a number of organisations, including perhaps most notably Save the Children UK, to adopt codes of conduct and child protection policies (Laville, 2009). By contrast, a number of organisations, including Medecins Sans Frontieres, have distanced themselves from the push towards PSEA codes, arguing that they make humanitarian response overly technocratic at the expense of ethical and political considerations (Hilhorst 2002, pp.201-202). Furthermore, Terry argues that by codifying standards, such issues are “no longer a tool of reflection but become ends in themselves to uphold.” (2000, p.3) The following section examines the extent to which codes of conduct have been adopted by humanitarian organisation as a tool for governing SEA conduct. Humanitarian Codes of Conduct This section presents the findings of a survey of references to codes of conduct made publicly available on the websites of 100 humanitarian organisations. iii This section aims to establish how widely codes of conduct are used in the humanitarian sector by examining which organisations refer to what codes of conduct, to whom these codes apply, and whether disciplinary measures and/or 4 accountability to certain stakeholders are mentioned. In doing so, this section aims to establish who and what is being governed. The sampling of humanitarian organisations was based on the membership of three broad-based humanitarian partnership bodies: Humanitarian Accountability Partnership, People in Aid and VOICE, and organisations that were referred to by these members. Given the role of these partnership bodies in promoting a more accountable sector, the findings are likely to show a higher level of accountability than exists in the humanitarian sector as a whole. Sampling was also limited to organisations with websites that have information available in English. As a result many nonEnglish speaking organisations and smaller organisations without a web presence were not included. This paper aims to overcome these biases by including: most of the largest humanitarian organisations, in addition to a range of smaller national and local organisations; organisations that are based and work in a wide range of countries; and organisations that are based on both secular and a range of religious principles. Furthermore, after examining 100 different organisations, a search of the internet showed that the field was essentially exhausted. These factors, combined with the relatively large sample size, mean that the findings of this paper can claim considerable generalisability within the sector. The research method involved examining each organisation's website for any reference to codes of conduct. The content of each website was scanned both manually and using the search function where available. Most websites were based on a similar format, with information categorised according to 'home', 'about us', 'what we do', 'where we work', 'get involved' and 'resources'. There was no standardised positioning of references to codes of conduct within NGO websites with references generally made in 'about us', 'what we do' and 'resources' categories or in subsections of these categories. This lack of standardisation made references to codes of conduct difficult to locate. The poor visibility of references to codes of conduct on many websites implies that many organisations do not place a large emphasis on these codes. A number of findings emerged from this research.iv Of the 100 organisations examined, 41 did not make any reference to a code of conduct. Four organisations made reference to a code of conduct, but it was either unclear to what code of conduct they were referring, or, if it was an organisationwide code, it was not made publicly available on the website. A total of 35 organisations referred to an external or third-party code of conduct, but not to an organisation-wide code. Of this, 28 referred to the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NonGovernmental Organization in Disaster Relief (ICRC Code), nine referred to the People in Aid Code of Good Practice (PIA Code), and five Australian organisations referred to the governmentbased ACFID Code of Conduct. None of these three codes refer to SEA issues. A range of other third-party codes were also mentioned.v None of these organisations referred to The Bulletin. In some cases the terms that organisations use to refer to third-party codes give an indication of their level of commitment to and perceived implementation of these codes. It is possible to identify a spectrum of commitment: from vague to firmly committed. Terms such as ‘signatory to’,vi ‘member of’ (Cord) or ‘have formally adopted’ (Troicare) express a strong commitment. At the other end of the spectrum the term 'guided by' (People in Need) is imprecise and expresses a much weaker commitment. Organisations that refer to third-party codes are generally weak at outlining how and to what extent the organisation can be held accountable to the code. Furthermore, these codes do not generally include PSEA. The vocabulary used in referring to codes of conduct also imply a spectrum of achievement: from those that imply that the organisation is in the process of adhering to a code, such as 'aims to work according to' (CAFOD) and 'seeks to adhere to' (Sungi), to those that imply achievement, including 'complies with' (Thailand Burma Border Consortium), 'implements in line with' (Medical Aid for 5 Palestinians) and 'designed and run according to' (Tearfund). While ‘process’ verbs imply that not all aspects of the code have been implemented, in all cases it is unclear which aspects of the organisation’s activities are compliant and which are not, thereby limiting their utility as a governance mechanism. ‘Achievement’ terms, by contrast, imply that the organisation is already fully compliant with the code in all aspects of their work. These terms fall into what Dean argues is the utopian trap of portraying governance as being fully effective (Dean 1999, p.33). In total, 18 organisations referred to and made publicly available on their website a general organisation-wide code of conduct. Of this 18, nine also referred to a third-party codevii and four have separate specific PSEA codes of conduct or child protection policies supplementing their general code.viii In addition to these 18 organisations, Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO) has a child protection code but does not refer to a code of conduct, and Lutheran World Services has a PSEA Code but refers to the ICRC for its general code of conduct. These organisation-wide codes differ in relation to whom they are applicable, whether they are signed, whether staff members have an obligation to report a breach of the code and disciplinary actions. Of the 20 organisations with PSEA, Child Protection or organisation-wide codes of conduct: 12 apply to all employees/personnel/staff; four apply to a subsection of employees; some codes also apply to interns, volunteers, representatives of the organisation, people visiting programmes and partners.ix These codes of conduct also vary in their scope of application. While most refer to workplace conduct, the codes of conduct of six organisations extend this, in varying degrees, to the private lives of their staff,x while the Muslim Aid Code, states explicitly that it is not applicable to the private lives of its staff. Three organisations state that their codes of conduct are not exhaustive, and that any additional issues should be referred to a supervisor, manager or line manager.xi Among organisation-wide codes, therefore, there is a high degree of variance in scope of applicability and designation of who is being governed. Among these codes it is also possible to identify a spectrum of enforceability. Of the 20 codes, 11 indicate that they should be signed,xii ten refer to a duty or obligation for staff to report any breach,xiii and ten refer to disciplinary actions including summary dismissal.xiv Furthermore, Diakonia notes that breaches may be referred to the police while the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) refers to legal action. Only five codes specify who the organisation is accountable to. xv This brief overview shows that these organisation-wide codes differ substantially in the extent to which they are explicit about enforcement mechanisms. This section has presented the findings of a survey of the references to codes of conduct made by 100 humanitarian organisations. These findings show that 59 per cent of organisations made at least some reference to a code of conduct, and that 20 per cent had their own organisation-wide codes. References to third-party codes tend to be unclear about the process through and extent to which the organisation and humanitarian workers can be held to account, and generally do not refer to SEA issues. PSEA in Organisation-wide Codes Having established in the previous section which organisations refer to codes of conduct, who are governed by these codes and the strength of these codes as a form of governance, this section will now examine which aspects of PSEA are included in the 20 organisation-wide codes identified in order to determine what forms of sexual behaviour are being governed. Of the 20 organisations, four - CODEC, Islamic Aid, ICCO and ICRC - do not make any reference to issues related to SEA or sexual conduct. Sexual exploitation is only prevented indirectly, for example, in the case of the ICRC Code, the requirement that the allocation of aid must be only based on need excludes the allocation of aid based on the provision of sexual favours. A further 6 three organisations - Islamic Relief, Muslim Aid and War Child NL- only make very brief references to SEA. The only reference to SEA in the War Child NL Code is that “no signatory is permitted to have sexual relations or any relation with any beneficiary that could be deemed to be abusive” while Islamic Relief sets out that “certain minimum standards of behaviour are observed in order to prevent sexual exploitation and abuse.” Seven organisations - Christian Aid, Diakonia, DRC, LWF, NCA, NRC and War Child UK - refer extensively to SEA issues. All refer to the sexual relations with a child and all except Diakonia explicitly state that a child is anyone under 18. Five state that mistaken belief of age is not a defence.xvi All seven refer to prostitution/commercial exchange of sexual services and all except Christian Aid to the exchange of sex for non-financial benefits. With the exception of Diakonia, all refer to the humanitarian aid worker having power or being in a position of authority. All except Christian Aid and Diakonia refer to the exploitation of vulnerable people; four refer to the responsibility to develop an environment in which SEA is not tolerated;xvii three refer to child abuse;xviii and six refer to relationships between beneficiaries and aid workers.xix DRC, NCA, NRC and War Child UK use the terms 'sexual abuse' and 'sexual exploitation' and generally bear a close resemblance to the language used and issues covered in The Bulletin. Five organisations - DRC, International Save the Children Alliance, IRC, MERCY Malaysia and War Child UK - refer explicitly to The Bulletin. The level of commitment to The Bulletin ranges from the DRC which directs the reader to it for guidance and interpretation to the IRC which states that it “vigorously enforces” The Bulletin. In covering PSEA, IRC and MERCY Malaysia only refer to The Bulletin. LWF and NCA refer to the ACT Alliance PSEA code of conduct. Four organisations - EveryChild, International Save the Children Alliance, PLAN and VSO - refer extensively to PSEA but are limited to the protection of children. These child-focused codes are the most extensive in terms of governing different SEA behaviour and in governing specific behaviour that increases the risk of SEA, including sleeping in the same bed as a child, spending excessive time alone with children away from others and assisting children with tasks of which they are capable. All four codes include: exploitation and abuse of children; the responsibility to develop an environment where abuse and exploitation is not tolerated; and sexual relationships with children (a child being under 18). International Save the Children Alliance specifies that mistaken belief of age is not a defence. In addition, EveryChild prohibits paying for sex and being paid for sex. These child-focused codes cover a broader range of sexual and non-sexual abuse by using the term 'exploitation and abuse (including sexual)’ rather than 'sexual exploitation and sexual abuse'. These child-focused codes are weaker than other PSEA codes in that they only aim to protect a specific demographic; however, they are more extensive in their coverage of high-risk behaviour. The similarity in the language used and issues covered by these codes suggests significant dialogue between these organisations or that one was used as a template for the others. Some codes use only a limited number of terms to refer to sexual activities, War Child UK, for example, primarily refers to sexual harassment, while others, such as the DRC, draw on a wide range of terms including SEA, sexual services and sexual relationships. Many of the terms used to indicate specific sexual activities are also imbued with sub-textual meaning. The terms ‘sexual abuse’ and ‘sexual harassment’ are blind to power inequalities. 'Sexual exploitation', by contrast, assumes that the aid worker is in a position of power and the intended beneficiaries are vulnerable and lack agency. Referring to 'prostitution' implies that the person has agency and has chosen to earn a living through selling sex. 'Cash for sex' implies an exchange, but is less commercial and agency-neutral. The context also influences the meaning of terms; if, for example, a code referred to 'forced prostitution' this would have the effect of removing agency. The term ‘sexual exploitation’ is broadly defined to encompass a range of sexual activities including 7 rape, forced prostitution, sexual slavery, survival sex and consensual relationships. This terminology indicates stark power inequalities between humanitarian workers and intended beneficiaries. Consensual sexual activities, including survival sex and consensual relationships, are conflated with coerced sexual activities, including rape and sexual slavery, with both portrayed as being inherently exploitative and abusive. In her analysis of The Bulletin, Otto argues that removing the often fine distinction between coerced and consensual sexual activities removes the agency, and in turn the dignity, of those intended beneficiaries who depend on and enter into such sexual activities voluntarily (2007, p.18). In all cases it is the conduct of the humanitarian aid worker that is being governed while the intended beneficiary or child represents the potential victim. While some codes include information about why beneficiaries, and particularly women and children, are vulnerable in humanitarian situations, organisation-wide codes generally pay scant attention to addressing the circumstances that make beneficiaries vulnerable to SEA including poverty and unequal power relations. These issues may be addressed by organisations elsewhere. One aspect that is not covered by any of these codes is the reasons why humanitarian aid workers undertake SEA. PSEA Codes as a Social Institution that Shapes Social Practice This section analyses the PSEA code discourse to establish the different mechanisms through which PSEA codes govern shape the practice of SEA by humanitarian workers. Foucault’s analytics of governance is used to identify the rationalities of governance underpinning PSEA codes and the ‘truths’ they formulate. Speech act theory is then used to examine the mechanism through which PSEA codes shape the behaviour of humanitarian workers including the generation of deontic power through the illocutionary force of speech acts. The final section will draw on Kratochwil’s work to examine how and what norms and values are used in the sector to guide judgement and adherence to PSEA codes. While it is not possible to evaluate the effectiveness of a PSEA through examining the psychological processes or the observable behaviour of individual humanitarian workers, the rapid and widespread adoption and advocacy of PSEA codes indicates that this tool has keyed into a perceived need for PSEA governance within the sector. The marked similarity between PSEA codes, particularly those relating to children, in terms of vocabulary and the sexual acts covered implies that they have been perceived as useful mechanism in the sector. An examination of the logic to which these codes of conduct appeal helps to establish the rationality behind PSEA codes as a form of governance. The premise that there is a discernible neo-liberal shift underway with governance increasingly decentralised and civil society organisations and individuals are responsible for governing their own conduct is central to Foucault’s work. At one level, the rise in NGO codes of conduct rather than the establishment of a State or quasi-State apparatus to govern the conduct of humanitarian workers is good example of this. Furthermore, an analysis of the vocabulary and grammar used in these codes shows some place responsibility for the governance of SEA behaviour at the level of the individual. Codes presented in the first person, for example 'I will/must', xx 'I have a duty to',xxi 'I will not/never',xxii and 'I will never knowingly',xxiii promote reflection on and identification with the code leading to a shift in responsibility for the governance of SEA behaviour from the organisation to the level of the individual. By shifting responsibility for governance to level of the individual, these codes also shift responsibility for SEA activity to the individual. Thus, if an organisation can show that it has provided adequate tools, training and support to enable the individual to govern their own SEA behaviour, the organisation is able to protect itself from scandals arising from incidents of SEA. Meanwhile those codes phrased in the second or third person, for example 'it has never been acceptable to,'xxiv'no signatory is permitted to',xxv 'staff must never', xxvi 'you should not'xxvii and 'it is prohibited to’,xxviii represent a more top-down mode of governance in which responsibility for the 8 governance of SEA remains at the level of the organisation. There is a clear distinction between codes that built on a defensive organisation-based logic, notably the protection of the reputation of the organisation,xxix and those that appeal directly a responsibility to do no harm to intended beneficiaries. Defensive logics imply that these codes were created to protect the organisation from the public scandals stemming from incidents of SEA rather than the protection of intended beneficiaries framing the publicity of SEA rather than SEA itself as the problem. The rationality of governance therefore is one of self-defence. Other codes, by contrast, appeal directly to a responsibility to not harm intended beneficiaries. The International Save the Children Alliance, for example, refers to a “commitment to protecting children” while the Norwegian Refugee Council refers to the need to “help staff to ensure that we protect the communities we work with”. The problem is the harm of beneficiaries. The rationality that underpins these codes is that SEA behaviour is unacceptable because of its harmful impact on affected persons and communities. These rationalities affect how the codes and the actions they prescribe are perceived. For example the silencing of SEA incidents may be an adequate resolution for organisations which base their codes on a defensive logic. ‘Do no harm’ codes, by contrast, require that SEA is governed directly. By examining the vocabulary used by PSEA codes it is possible to identify certain ‘truths’ which these codes both work to create and imply that exist. The phrasing of PSEA codes implies that it is an external reality that there is consensus that SEA is unacceptable and that the code merely a codification of this reality. At the same time PSEA codes develop and use terms such as ‘exploitation’ and ‘abuse’ which have strong negative connotations and depict one who perpetrates such acts as morally corrupt. The use of such morally potent language constricts the scope for dialogue and works to silence dissenting opinions. In such a manner these PSEA codes create the very ‘truth’ that they imply already exists. The vocabulary used often also implies that there is external consensus that affected populations are vulnerable and victimised, yet terms such as forced sex, sexual slavery and reference to vulnerable population actually work to create this ‘truth’. This section will now turn to examine what type of social institution humanitarian codes of conduct represent before turning to how they function. Based on the findings of the ‘Humanitarian Codes of Conduct’ section of this paper it is possible to distinguish between four distinct forms of social institutions established by humanitarian codes of conduct: third party codes of conduct which are signed by an organisation; third party codes of conduct which are committed to but not signed by an organisation; organisation-wide codes of conduct which are signed by individual humanitarian workers; and finally codes of conduct which are committed to but not signed by humanitarian workers. While the distinction between these social institutions is not always clear cut, the rules that bind the practice differ in important aspects. Codes of conduct which are not signed by either humanitarian organisations or individuals represent a social institution akin to a promise or a commitment. The rules establishing such institutions are relatively simple in that they just require an individual or organisation to pledge their commitment to the rules. When an organisation or individual signs a code of conduct, and especially when a code of conduct is included in the mandate of an organisation or employment contract, the code represents a more formalised ‘contractual’ form of social institution. When an organisation expresses its commitment to a code of conduct its stakeholders (including beneficiaries, donors, partner and implementing organisations, and employees), the humanitarian sector and the general public represent the receiver of the promise. In making the commitment the organisation must represent itself as a moral agent that will work to ensure the code is implemented or risk this moral status. Similarly when an individual humanitarian worker expresses a commitment to an organisation-wide code the individual is representing themselves as a moral agent to the organisation. In the case of a contractual code the receiver is obliged to monitor and support the 9 organisation in abiding by the code. When an organisation or individual is not aware of the code, they cannot be rule-bound by the social institution as they have not represented themselves as a moral agent in committing to the institution. This section will now turn to examine the deontic force of PSEA codes and how this is generated through the illocutionary force of speech acts. Firstly, however, what evidence is there that PSEA codes are imbued with deontic power? Different codes use different auxiliary verbs including ‘may’, ‘will’, ‘must’, ‘shall’, ‘should’ and ‘have to’xxx which imply different degrees of obligation. For example ‘will' in the first person shows the willingness and determination of the agent, while 'must' and 'have to' are used to express something that is obligatory.xxxi Finally, ‘duty’ has strong overtones of a debt due to someone and appeals to moral obligation; ‘responsibility' has less weight of obligation and a greater sense of personal accountability; while ‘prohibited’ removes all moral connotations by categorically ruling out a certain action. These terms, create obligations, responsibilities and duties to either perform or not perform certain actions. In other words, these terms are, to differing extents, imbued with deontic power as defined by Searle. How is this deontic power generated? When an organisation or humanitarian worker signs or commits to a PSEA code of conduct, they are effectively presenting themselves as a moral agent. It is this self-representation which generates deontic power. By committing to a code of conduct, the organisation or worker can then be held account to this commitment by the receiver or by the general public. When this commitment to a PSEA code is violated for reasons other than exceptional circumstances stemming from the structure of the normative order, the promiser surrenders their reputation as a moral agent. Humanitarian organisations are founded on the moral imperative to assist those in need. As a result, particularly given the wide and damaging publicity of incidents of SEA, the removal of moral agency represents a powerful threat. The removal of moral agency is a considerably less powerful threat at the level of the individual humanitarian worker due to the size, diversity and poor communications within the humanitarian sector. In spite of recent efforts of actors including the Humanitarian Accountability Partnership International, humanitarian workers are often hired in emergency situations without proper background and reference checks due to time constraints (Maxwell 2008, p.15). As a result, when humanitarian worker violates a code of conduct, this will not necessarily impact their wider moral agency. This undermines the illocutionary force of the commitment. Without widespread reference and background checks in the humanitarian sector, codes of conduct will be limited in their ability to prevent SEA. A general belief in the reasonableness of a standard is also required for speech acts to generate deontic power (Kratochwil 1984, p.698). PSEA codes cover a range of sexual activities: from acts which are widely condemned, such as the sexual abuse of children, to acts which are considered morally ambiguous such as relationships between beneficiaries and aid workers. The diversity of sexual activities included in PSEA codes indicates disagreement over which activities are considered acceptable and which are not, and, in turn, what standards are considered reasonable and which are not. For example some argue that the discouragement of consensual sexual relations between humanitarian workers and intended beneficiaries aims to protect the latter. However, others have argued that this alienates humanitarian workers from the people they aim to assist, reinforces the portrayal of women in developing countries as ‘victims’ and eliminates the possibility of sex as a form of labour, pleasure or anything other than abusive behaviour (Otto 2007). Just as different organisations disagree over which standards are reasonable, a diversity of opinions also exists within organisations. If this belief in the unreasonableness of a standard is intersubjectively understood then the PSEA code will not be able to summon the deontic power required to shape behaviour. 10 The literature points to a number of reasons that have been used to justify acts of SEA including a 'boys will be boys' mentality and the psychological/physical difficulties of operating in a postdisaster or post-conflict situation (See Otto 2007, p.18; Orford 1996, p.378). Inter-subjectively understood norms and values represent a guidance tool for assessing the validity of the reasons given for a violation of a social institution. However, it is uncertain what exactly constitutes norms and values in the humanitarian setting. Stoddard points to three key value-bases which underpin humanitarian organisations: the religious, the ‘Dunantist’ and the ‘Wilsonian’. The religious tradition is the oldest, based on the tenets of compassion and charitable service. The second tradition, termed the Dunantist tradition after Henri Dunant, founder of the ICRC, codified what is now commonly accepted as the core humanitarian principles (see below). Subsequent NGOs built on this tradition include Save the Children UK, Oxfam and MSF (Stoddard 1998, p.32). The third ‘Wilsonian’ tradition, which typifies most US NGOs, stems from President Woodrow Wilson’s ambition of “projecting US values and influence as a force for good in the world” and is seen as being compatible with US foreign policy (Rieff, 2002; Stoddard 1998, p.32). These traditions continue to underpin the value-base of humanitarian organisations. Some PSEA codes appeal to organisation-wide values. For example the NCA code states that it “is intended to serve as a guide for all staff in how to uphold the ethical foundations of the organisation's views and actions.” However, given the high turn-over of jobs, fluidity between different organisations and an increase in careerist humanitarian workers, one cannot assume that the value-base of an organisation is aligned with personal values of its employees. Further qualitative interview-based research is required to gauge the extent to which humanitarian workers seek and find employment in an organisation in-line with their own values. Other codes of conduct appeal to intersubjectively understood humanitarian principles. There is general consensus within the sector that humanitarian assistance should be based on the principles of: humanity, that all humans are equal and that we should work to alleviate human suffering wherever it is found; impartiality, that that aid should be provided on the basis of needs alone regardless of race, religion, or politics; and independence from institutional donors, religious and other pressure groups. Dunantist organisations, especially the ICRC, also consider neutrality: not taking sides in political or religious disputes, to be a core principle (Walker 2004). None of these intersubjectively understood humanitarian values cover SEA. This undermines their ability to function as a strong guidance mechanism for judging the validity for the reasons given for violations. Some organisations and NGO partnerships including Humanitarian Accountability Partnership have worked to introduce another core humanitarian value: ‘to do no harm’, however more research is required to determine how intersubjectively understood this value has become (Pitotti 2011, p.5). An interesting avenue for further research may be to examine to what extent this principle has been designed specifically as a PSEA guidance tool. Stoddard argues that despite the different mandates, histories, cultures and interests in the humanitarian sector, the epistemic and collegial links among staff members of the major NGOs are strong (Stoddard 1998, p.32). This may indicate that norms and values are established between staff members which are in contact with each other on a regular basis. Given the divide between humanitarian workers based in the field and those based at headquarters this could raise important questions about the intersubjectiveness of norms and values. Within the humanitarian sector there is acknowledgement that field-based norms are more driven by needs and the delivery of emergency assistance, while headquarter-based staff, which are removed from the immediate impact of the crisis, deal more with overarching issues including strategic direction, coordination and the development of policy (Stoddard 1998, p.31). Research is required to understand whether there is a 11 normative divide between field- and headquarters-based staff and whether as a result certain reasons for SEA are more readily accepted in the field. If this is the case it has important policy implications for how humanitarian response should be delivered and how PSEA codes should be supported. Finally reports of widespread SEA in specific humanitarian response situations including postindependence East Timor in 2001 and South Sudan in 2011 (information collected informally by author) warrant the examination of other factors which influence norms and values in a given humanitarian response including: the political situation in country particularly whether it is postconflict or post-independent; the level of interaction between the humanitarian workers and the local population; the role of religion and culture particularly whether alcohol consumption is widespread; and the influence of the behaviour of high-level humanitarian workers. Conclusion This paper has examined how humanitarian codes of conduct act as a mechanism through which the SEA behaviour of humanitarian workers is shaped. A survey of references to codes of conduct made by 100 non-government humanitarian organisations shows that these references are widespread but that many of these are based on weak and unclearly specified commitments to third-party codes that do not refer to SEA issues. This survey found that of the 100 organisations surveyed, only 13 have substantial SEA codes of conduct. An analysis of the PSEA code discourse yielded a number of interesting observations: PSEA codes attempt to create the ‘truth’ that SEA is considered unacceptable and that intended beneficiaries are vulnerable, there are two key types of rationalities that underpin these codes- defensive and ‘do no harm’ rationalities, and it is possible to identify four different types of social institutions created by humanitarian NGO codes of conduct. The diversity of the sector, the lack of reference checks and the lack of clear consensus on the reasonableness of PSEA code standards limits the ability of PSEA codes to generate deontic power and thereby shape SEA behaviour. Meanwhile it is difficult to determine what the norms and values are that underpin the humanitarian sector and provide guidance for judging violations of PSEA codes. While there is some evidence for a field/headquarters norm and value divide more research is needed. SEA not only has short- and long-term psychological and physical effects on those intended beneficiaries, humanitarian workers and communities involved. When SEA is widespread it can significantly influence post-crisis reconstruction and gender relations within the society as a whole. In this context, examining how PSEA codes shape SEA behaviour is paramount. 12 Appendix 1: Humanitarian Organisation Surveyed Do not refer to a code of conduct (41) Adventist Development and Relief Agency, African Network for the Prevention and Protection against Child Abuse and Neglect, Agence d'Aide à la Coopération Technique et au Développement (ACTED), All India Disaster Mitigation Institute, Amel, AmeriCares, Baptist World Alliance, Caritas International, Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives (CPDI), ChildFund International, Children First, Church of Sweden, Church's Auxiliary for Social Action's (CASA), Community and Family Services International, Doctors World Wide, GOAL, Health Poverty Action, HealthNet International TPO, HelpAge International, HIJRA Somalia, International Medical Corps UK, International Medical Corps US, Khwendo Kor, KinderUSA, Kohsar Welfare and Education Society, Medica Mondiale, Mercy Corps, Medecines Sans Frontieres, Naba'a, Office Africain pour le Développement et la Coopération (OFADEC), Oxfam America, Peacebuilding UK, Saibaan Development Organisation, Samaritan's Purse, Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund, Society for Safe Environment and Welfare of Agrarians in Pakistan (SSEWA-PAK), Sustainable Environment & Ecological Development Society (SEEDS), WaterAid, Yakkum Emergency Unit (YEU), Shelter for Life International and Solidarites International. Code of Conduct Not Specified/Not Publicly Available (4) FinnChurchAid, Najdeh, PMU Interlife and Viva Network. Refer to a Third-Party Code of Conduct (35) ActForPeace, Action Against Hunger UK, Antareas Foundation, Australian Aid International, British Red Cross, CAFOD, CARE Australia, CARE International Secretariat, CESVI, Church World Service, COAST Trust, CONCERN Universal, Concern Worldwide, Cord, DanChurchAid, Focus Humanitarian Assistance, Human Relief Foundation, International Aid Services, Malteser International, Medair, Medical Aid for Palestinians, Merlin, Mines Advisory Group, Mission East, Muslim Aid Australia, Oxfam, People in Need, Sungi, TEAR Australia, Tearfund, Thailand Burma Border Consortium, Trocaire, Women's Refugee Commission, World Vision International, RedR UK, Organisation-wide Code of Conduct and/or Child Protection Code/PSEA Code (20) Christian Aid, Community Development Centre (CODEC), Danish Refugee Council (DRC), Diakonia, EveryChild, ICCO, International Alert, International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC), International Rescue Committee (IRC), International Save the Children Alliance, Islamic Relief, Lutheran World Federation (LWF), MERCY Malaysia, Muslim Aid UK, Norwegian Church Aid (NCA), Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), PLAN, Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO), War Child Netherlands and War Child UK. 13 Bibliography Barth, E. (2004) ‘The United Nations Mission in Eritrea/Ethiopia: Gender(ed) Effects’. In L. Olsson, I. Skejlebaek, E. Barth and K. Hostens (eds) Gender Aspects of Conflict Interventions: Intended and Unintended Consequences. International Peace Research Institute, Oslo. Buzan, B., O. Wæver and J. Wilde (1998) Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder. London: Lynn Reinner Publishers. Davis, J. (2010) ‘From Logic to Logics?’, in O. Kessler, R. Hall, C. Lynch and N. Onuf (eds.) On Rules, Politics and Knowledge: Friedrich Kratochwil, International Relations and Domestic Affairs. London. Palgrave Macmillan. Dean, M. (1999) Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. Sage Publications, London. Ebrahim, A. (2003) ‘Accountability in Practice: Mechanisms for NGOs’. World Development. 31(5). pp. 813-829. Foucault, M. (1981) ‘Omnes et singulatim: towards a criticism of ‘political reason’ in: S. McMurrin (ed.) The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. 2. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 22354. Foucault, M. (1991a) ‘Governmentality’ in G Burchell, C Gordon, P Miller (eds.) The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf. pp. 87-104. Foucault, M. (1991b) ‘Questions of Method’ in G Burchell, C Gordon, P Miller (eds.) The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf. pp. 73-86. Foucault, M. (1993) ‘About the Beginning of the Hermeneutics of the Self’ (Transcription of two lectures in Darthmouth on Nov. 17 and 24, 1980) in Mark Blasius (ed.) Political Theory. 21(2). May, 1993 pp.198-227. Hall, R. (2010) ‘Trust Me, I Promise! Kratochwil’s Contributions toward the Explanation of the structure of Normative Social Relations’ in O. Kessler, R. Hall, C. Lynch and N. Onuf (eds.) On Rules, Politics and Knowledge: Friedrich Kratochwil, International Relations and Domestic Affairs. London. Palgrave Macmillan. Harrington, A. (2005) ‘Victims of Peace: Current Abuse Allegations against U.N. Peacekeepers and the Role of Law in Preventing them in the Future’. ILSA Journal of Comparative & International Law. 12(630). Hilhorst, D. (2002) 'Being Good and Doing Good? Quality and Accountability of Humanitarian NGOs'. Disasters. 26(3). pp. 193-212. Hindess, B. (1996) Discourses of Power. From Hobbes to Foucault. Oxford: Blackwell. Humanitarian Accountability Partnership. (2010) HAP Standard 2010. HAP, Geneve. Humanitarian Accountability Partnership and Save the Children UK (2011) PSEA Conference for Humanitarian Practitioners. London. 30-31 March 2011. 14 International Rescue Committee (2003) ‘Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Training Module’, Gender Based Violence Program. Sierra Leone. Kessler, O., R. Hall, C. Lynch and N. Onuf (2010) ‘Introduction’ in O. Kessler, R. Hall, C. Lynch and N. Onuf (eds.) On Rules, Politics and Knowledge: Friedrich Kratochwil, International Relations and Domestic Affairs. London. Palgrave Macmillan. Kihunah, M. (2007) ‘Building Accountability: Sexual Abuse by UN Peacekeepers’. Disarmament Times. 1 April 2007. King, G., R. Keohane and S. Verba (1994) Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton University Press, Princeton. Klotz, A. and C. Lynch (2007) Strategies for Research in Constructivist International Relations, New York. ME Sharpe. Kratochwil, F. (1984) ‘The Force of Prescriptions’, International Organisation. 38. pp.685-708. Kratochwil, F. (1989) Rules, Norms and Decisions: On the Conditions of Practical and Legal Reasoning in International Relations and Domestic Affairs, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lalor, K. (2004) ‘Child Sexual Abuse in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Literature Review'. Child Abuse and Neglect. 28. Laville, S. (2009) ‘Paedophile who Worked for Save the Children Jailed’. The Guardian. 29 Wednesday 2009. Available at http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/jul/29/children-charity-workerpaedophile-jailed (accessed 18 June 2011). Lemke, T. (2000) ‘Foucault, Governmentality, and Critique’. Paper presented at the Rethinking Marxism Conference, University of Amherst, 21-24 September 2000. Maxwell, D. et al (2008), Preventing Corruption in Humanitarian Assistance, Berlin. Transparency International. Morris, C. (2010) 'Peacekeeping and the Sexual Exploitation of Women and Girls in Post-Conflict Societies: A Serious Enigma to Establishing the Rule of Law'. Journal of International Peacekeeping. 14. pp. 184-212. Ndulo, M. (2009) 'The United Nations Responses to the Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Women and Girls by Peacekeepers during Peacekeeping Missions'. Cornell Law Faculty Publications. 59. Odello, M. (2010) ‘Tackling Criminal Acts in Peacekeeping Operations: The Accountability of Peacekeepers’. Journal of Conflict and Security Law. 15(2). pp. 347-391. Orford, A. (1996) ‘The Politics of Collective Security’. Michigan Journal of International Law. 17. pp. 373-410. Pitotti, M. (2011) ‘Report by Refugee & Migration Affairs, US Mission to the UN’ presented at Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA) Conference, HAP International. Geneva. 11 May 2011. 15 Risse, T. (2000) ‘“Let’s Argue!”: Communicative Action in World Politics’. International Organisation. 54(1). Rudén, F. and M. Utas, ‘Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by Peacekeeping Operations in Contemporary Africa’. The Nordic Africa Institute Policy Notes. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala. Schimmelfennig, F. (2001) ‘The Community Trap: Liberal Norms, Rhetorical Action and the Eastern Enlargement of the EU’. International Organisation. 55(1). Searle, J. (2005) ‘What is an institution?’ Journal of Institutional Economics. 1(1). pp. 1-22. Siddiquee, N. and G. Faroqi (2009) ‘Holding the Giants to Account? Constraints on NGO Accountability in Bangladesh’. Asian Journal of Political Science. 17(3). pp. 243-264. Spencer, S. (2005) 'Making Peace: Preventing and Responding to Sexual Exploitation by United Nations Peacekeepers'. Journal of Public and International Affairs. 16. pp. 167-181. Stephenson, M. (2005) ‘Making Humanitarian Relief Networks More Effective: Coordination, Trust and Sense Making’. Disasters. 29(4). Stoddard, A. (1998) ‘Humanitarian NGOs: Challenges and Trends’ in HPG Report. Center on International Cooperation. New York University. Terry, F. (2000) The Limits and Risks of Regulation Mechanisms for Humanitarian Action. MSF: Centre de Reflexion sur L'Action et les Savoirs Humanitaires. Turk, V. and E. Eyster (2010) ‘Strengthening Accountability in UNHCR’, International Journal of Refugee Law. 22(2). pp. 159-172. UNHCR and Save the Children UK (2002) ‘Sexual Violence and Exploitation: The Experience of Refugee Children in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone: Note for Implementing and Operational Partners’. Available at http://www.unhcr.org/ [accessed: 21 May 2011]. UN Secretary General (2003) Secretary General's Bulletin: Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (ST/SGB/2003/13). Walker, P. (2004) ‘What is a Professional Humanitarian?’ The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance. 14 January 2004. Willitts-King, B. and P. Harvey (2005) 'Managing the Risks of Corruption in Humanitarian Relief Operations: A Study for the UK Department for International Development', Overseas Development Institute. 16 i In the context of this paper the term codes of conduct does not include those codes that are limited in scope to governing the use of images, organisational logos etc. ii Including Keeping Children Safe Alliance, Humanitarian Accountability Partnership International and People In Aid. iii See Appendix 1 for a full list of surveyed organisations. iv See Appendix 1 for a breakdown of the key findings. v These include: Basic Rules of Humanitarian Aid Coordination Committee Germany, Micah Network Guidelines on Partnership, International Rescue Committee (IRC) Way Standards for Professional Conduct, International NGO Accountability Charter and Global Humanitarian Platform Principles of Partnership. In addition to Codes developed by: Association of International Development Agencies (AIDA), British NGO Network (BOND), ConCord, Dochas, EU-Cord, European Voluntary Service (EVS), Humanitarian Charter, European Commission: Humanitarian Aid & Civil Protection (ECHO), Fundraising Institute Australia (FIA), Indsamlingsorganisationernes Brancheorganisation (ISOBRO), InterAction and Verband Entwiklungspolitik Deutcher Nicht-Regierungs (VENRO). vi Action Against Hunger, Australian Aid International, British Red Cross, CARE Australia, CARE International, CONCERN Universal, DanChurchAid, Human Relief Foundation, International Aid Services, Medair, Mines Advisory Group, Muslim Aid Australia and Oxfam. vii Organisations that have a code of conduct and refer to a third-party code: Christian Aid, EveryChild, ICCO, International Save the Children Alliance, Islamic Relief, IRC, MERCY Malaysia, Muslim Aid and NCA. These codes include the ICRC Code, the ACT Alliance PSEA Code, PIA Code, BOND Code, Principles of Partnership of Global Humanitarian Platform and, in the cases of MERCY Malaysia, War Child UK and EveryChild, The Bulletin. Organisations that have a code of conduct and do not refer to a third-party code: CODEC, Diakonia, DRC, ICRC, International Alert, NRC, PLAN, War Child NL and War Child UK. viii Christian Aid, International Save the Children Alliance, Muslim Aid and PLAN. ix Applies to all employees/personnel: EveryChild, Christian Aid, CODEC, International Save the Children Alliance, Islamic Relief, International Rescue Committee (IRC), Lutheran World Federation (LWF), Muslim Aid, MERCY Malaysia, Norwegian Church Aid (NCA), Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and PLAN. Diakonia, DRC and War Child NL apply to some employees (generally those employed in overseas operations). Different sections of the War Child UK code apply to different personnel. The IRC code also applies to interns; the codes of Everychild, Muslim Aid, NRC, War Child NL also apply to representatives of the organisation; EveryChild, IRC, Muslim Aid, MERCY, NRC and VSO codes also apply to volunteers; PLAN and War Child NL codes also apply to people visiting programmes; and Muslim Aid and Islamic Relief codes also apply to partners. x Christian Aid, CODEC, LWF, NCA, PLAN and War Child UK xi NRC, PLAN and War Child UK xii Christian Aid, DRC, EveryChild, International Save the Children Alliance, LWF, MERCY Malaysia, Muslim Aid, NCA, NRC, PLAN and War Child NL. xiii Christian Aid, CODEC, DRC, International Save the Children Alliance, Muslim Aid, NCA, NRC, PLAN, War Child NL and War Child UK xiv Christian Aid, Diakonia, DRC, EveryChild, LWF, NRC, PLAN, VSO, War Child NL and War Child UK. xv International Alert, ICCO, ICRC, Islamic Relief and LWF refer to a range of stakeholders including “donors and beneficiaries” (LWF) and “our creator, our supporters, our beneficiaries, our colleagues, the authorities.”(Islamic Relief). xvi DRC, LWF, NCA, NRC and War Child UK. xvii NCA, NRC, LWF and War Child UK xviii Christian Aid, DRC and War Child UK xix NCA, LWF NRC, DRC, War Child NL and War Child UK xx Christian Aid, DRC, EveryChild and PLAN xxi Muslim Aid xxii Christian Aid, DRC, EveryChild, NCA, NRC, War Child UK and War Child NL xxiii Christian Aid xxiv NRC xxv War Child NL xxvi VSO xxvii Diakonia xxviii Examples of the vocabulary/grammar used includes: 'I will/must'(Christian Aid, DRC, EveryChild and PLAN); 'I have a duty to' (Muslim Aid); 'our staff have a responsibility to’ (Islamic Relief); 'I will not/never’ (Christian Aid, DRC, EveryChild, NCA, NRC, War Child UK and War Child NL); 'it has never been acceptable to' (NRC); 'I will never knowingly' (Christian Aid); 'no signatory is permitted to' (War Child NL); 'staff must never' (VSO); 'you should not' (Diakonia); and 'it is prohibited to’ (Diakonia, LWF, NCA, NRC and War Child UK). xxix Including Christian Aid, EveryChild, Muslim Aid, PLAN and War Child NL. 17 xxx 'Have to' is not strictly speaking a modal auxiliary verb, but in this case has similar characteristics. 'Shall' in the third person denotes a command or obligation, it is used to express strong intentions and the determination of the speaker. Shall is also often used in legal documents, thus giving an impression of greater legal authority. 'Should' by contrast is used to describe an ideal behaviour, and imparts a normative meaning. 'Will' in this first person indicates the willingness and determination of the agent and is more voluntary. In the context of the codes, 'may' indicates permission, and 'may not' the lack of permission. Both 'must' and 'have to' are used to either express something that is obligatory, something that is forbidden or a resolution. They both also indicate that the beliefs are strongly held; 'must' is associated with personal obligation, is used in giving orders and instructions for the future, while 'have to' is less emphatic and indicates impersonal necessity and is less like a direct order. xxxi 18