Historical Thinking Concepts: A Guide for Students

advertisement

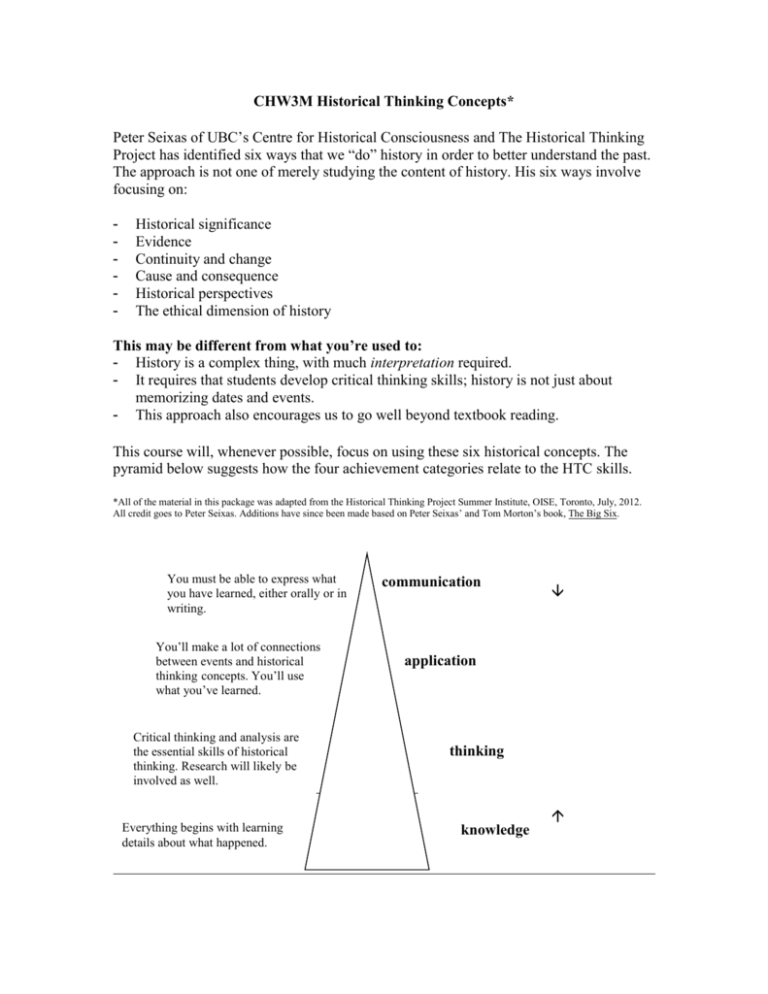

CHW3M Historical Thinking Concepts* Peter Seixas of UBC’s Centre for Historical Consciousness and The Historical Thinking Project has identified six ways that we “do” history in order to better understand the past. The approach is not one of merely studying the content of history. His six ways involve focusing on: - Historical significance Evidence Continuity and change Cause and consequence Historical perspectives The ethical dimension of history This may be different from what you’re used to: - History is a complex thing, with much interpretation required. - It requires that students develop critical thinking skills; history is not just about memorizing dates and events. - This approach also encourages us to go well beyond textbook reading. This course will, whenever possible, focus on using these six historical concepts. The pyramid below suggests how the four achievement categories relate to the HTC skills. *All of the material in this package was adapted from the Historical Thinking Project Summer Institute, OISE, Toronto, July, 2012. All credit goes to Peter Seixas. Additions have since been made based on Peter Seixas’ and Tom Morton’s book, The Big Six. You must be able to express what you have learned, either orally or in writing. You’ll make a lot of connections between events and historical thinking concepts. You’ll use what you’ve learned. Critical thinking and analysis are the essential skills of historical thinking. Research will likely be involved as well. Everything begins with learning details about what happened. communication application thinking knowledge Historical Significance How we select what/who should be taught, remembered, researched and learned about the past by using criteria. We don’t accept that everything that ever happened is significant. We attach significance to certain people and events by using criteria. Guideposts for Historical Significance: 1. Does it result in change? - With deep consequences (profundity – how?). - For many people (quantity). - Over a long period of time (durability). 2. Is it revealing? - Does it help us understand the past? - Historiography (the study of how history has been written and interpreted over the years) has changed a lot over the decades. Now we study ordinary people (e.g., lower classes, peasants, slaves, women) who didn’t necessarily cause change themselves but who experienced change. So events chosen as historically significant reveal this unrecognized impact. 3. Does it occupy a key place in a meaningful narrative? - Resonates with people today by shedding light on issues or problems of today. - History is constructed, meaning significance is attributed to events; not everything that ever happened is considered significant. 4. Different people (groups) at different times have different views of what is considered to be significant. In Your Life Sketch out the most significant events in your life so far. Then analyze how you came to your answers. This is how you develop criteria for assessing significance. CHW3M The 100 objects from the British Museum were chosen because they are significant in some way. The author’s choices are an interpretation with which some people and historians may disagree. Dragon’s Den Mesopotamia is an exercise to help you understand why certain innovations are considered to be significant. Evidence Students must be taught directly how to use evidence from the past by learning the skills of how to work with original material, beyond just determining the bias in a primary source document. To do this they must ask good questions and make inferences. The main question is: “how do we know what we know about the past?” Guideposts for Evidence 1. We interpret history based on the inferences we make about primary sources from the past. They can range from the most minute traces, such as sherds of pottery, to written records. 2. A source alone isn’t evidence. We need to ask questions about it for it to become evidence. 3. Students have to source a piece of evidence when they study it. - Ask questions about when it was created, who created it. - What is the purpose of the author in creating this document (or object)? - What values and worldview do they hold? - The author of the document may be aware of these factors, or he/she may not be aware of them (conscious or unconscious). 4. Sources have to be considered within their own historical setting. - What is the context from which the evidence comes? - Under what social/economic/political, etc. conditions was it created? - In simple language: what historical events were occurring when it was created? 5. When we ask questions about a source these allow us to make inferences. Since we can’t know these answers are necessarily correct we have to corroborate them, meaning we have to check other sources to see if our inferences are “correct”. In Your Life Identify everything you have done in the last 24 hours. Make a list of traces left over from these actions. Which are purposeful, which are accidental? Are these traces likely to be preserved? CHW3M Make a list of all the primary evidence sources in the course so far, not just written. Continuity and Change History is more than a list of events. How do we organize its complexity and its flow? One way is by looking at the relationship between events/developments in terms of continuity (what remains the same) and change (what changes).They can both exist at the same time; they are not opposites. Seixas has developed guideposts for students to analyze these relationships. Guideposts of Continuity and Change: 1. Continuity and change can occur at the same time and are often closely interwoven. It helps to begin by examining chronologies, events listed in an order from earliest to latest. However, the list alone is not to be memorized. It is to be analyzed. 2. The pace of change isn’t always the same. - How fast or slow does change occur? - Turning points are especially interesting to look at. - Rivers of change and road maps are useful analogies because we can consider speed, depth, obstructions and other things that both hinder and encourage change. 3. Progress and decline - These are ways of evaluating change over time. - For whom? It depends on who is looking at the evidence. - In what? - Progress in something can lead to decline in something else. 4. Periodization - How we divide time up (bundle it into periods) is interpretative. In Your Life Make a timeline of your life. Analyze it by looking at things that remain the same over time and aspects of your life that have changed. Think of a car trip you went on once during your life. What events slowed it down? What events sped it up? CHW3M Did the Egyptians themselves label their kingdoms as old, middle and new? Or are those labels applied by historians studying Egypt? Cause and Consequence There is a complexity to the relationship between events, often seen through an exploration of their causes and consequences. Seixas asks: “Why do events happen, and what are their impacts?” History is actually more about the why than the what, perhaps to your surprise. Guideposts of Cause and Consequences 1. There are multiple causes and consequences, both short- and long-term Constructing Causal Webs and Questions About Them: - What lay behind X? How did X make a difference? What kind difference did X make to Y? Why was X so shocking (surprising, etc.)? Why did X happen in year Y? Why did X happen so quickly (slowly, peacefully, violently, etc.)? 2. Causes that lead to a change vary in influence - Some are more important. Students have to assess or weigh which have more influence. Questions on Influence: - Did X make Y happen, or did X just make Y more likely? What was the real cause of X? Was it only X to blame for Y? Which person/event/development did most to shape people’s lives in …? 3. Change results from two related types of factors - Historical actors – people who take actions. - Social/political/cultural conditions within which actors operate. 4. Historical actors can’t predict the effects of conditions, opposing actions and unforeseen reactions - This generates unintended consequences. 5. The events of history weren’t inevitable - If any single action or condition of an event had been altered it may have turned out differently. - Counterfactuals can be constructed: what would have happened if… In Your Life Write a personal timeline of all the events that brought you to this class. Make sure to include not only the most recent things (short-term) that happened but also events, actions and emotions that are more medium- and long-term. Have your personal plans always turned out exactly as you wished? CHW3M The rise and fall of Mesopotamian states did not just happen. Each rise was caused by certain factors, while each fall left consequences in its wake. They all need to be analyzed in order to piece together their meaning. Historical Perspectives Understanding the people of the past requires understanding the different social, cultural, intellectual and even emotional contexts that shaped people’s lives and actions in the past. Guideposts for Historical Perspective 1. There’s a big difference between the worldviews of people today (beliefs, values, motivations) and the worldviews of people in the past. 2. Avoid presentism (imposing our own standards on the past) o How is their role/position different from a similar person or group today? o Compared to what we face today, what relevant circumstances were different for them in the past (e.g., technology, media, economy, religion, family life, communication, recreation, etc.)? 3. Historical actors operated within a historical context that must be recognized. 4. Taking the perspective of historical actors does not mean identifying with them o Students do not have to feel what it would have been like to be a person from the past (often this cannot be known and we shouldn’t try). o The question is not: how might I feel in a given historical situation. It is how might they have felt. 5. There are many different historical perspectives on events in the past held by different historical actors. o Students need to recognize these and analyze these. In Your Life Do you have anyone in your family history that had a name that is no longer popular today? Would that person’s name have been considered “funny” then? CHW3M Don’t quickly dismiss Hammurabi’s laws as unfair because they’d be seen that way today. Take the time to study how they would be seen in their own time and place. Ethical Dimension of History Seixas identifies the following problem with studying history: “we expect to learn something from the past that helps us in facing the ethical issues of today, but we always risk anachronistic impositions of our own standards upon the past (presentism).” He asks: “How can history help us to live in the present?” Guideposts for Ethical Dimension 1. Making judgments about actors and actions in the past is part of historical writing. 2. Students can only make proper ethical judgments when they consider the historical context of the historical actors they are reading about. 3. People today cannot make judgments about the past using current standards of what is right and wrong. 4. People today can think about our responsibility to remember and respond to injustices of the past, as well as contributions and sacrifices made in the past. 5. Helping make judgments about contemporary issues, informed by history. Lessons from the past are a very tricky subject. Caveats About Ethical Dimension (especially regarding controversial events) - When studying controversial events, show that they are not isolated from their context. Find dissenting voices to supposedly monolithic views of events in history. Identify how actors were judged by their immediate surroundings. Ask what information people had at the time. Beware: the past can become a current political issue. In Your Life Think of a movie you’ve seen in which there were heroes and villains. How did the producer/director/writer get you to sympathize with the hero and dislike the villain? Did the movie have a lesson or moral message? Can the same questions be asked of textbooks? CHW3M We have a lot of fun studying ancient history. Are we ignoring the more serious nature of the events that occurred?