WMNST 604 Gender, Culture and Representation (Colwill)

advertisement

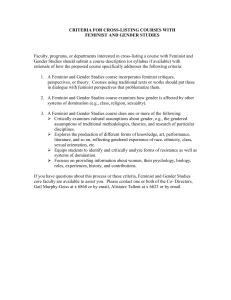

Women’s Studies 604: Fall 2011 Gender, Culture, and Representation Dr. Elizabeth Colwill Office: AL 311; Office Hrs: 10-12 Tues., 3:30-6 Thurs., and by appointment. Email colwill@mail.sdsu.edu. What is culture? How do institutions, nations, culture brokers, and communities produce, transmit, and transform cultural values and (sexual, gendered, racial, religious, national, ethnic) identities? What kinds of cultural and political work do representations of women and femininity, men and masculinity perform? How do people in diverse social locations make meaning of what they see, hear, and feel during visual, oral, and corporeal performances? How have marginalized groups appropriated and reinterpreted specific cultural genres to define their own personal and collective identities? How do the politics of representation and self-presentation--who speaks for whom, under what conditions, and to what ends?--illuminate the working of power? These are among the guiding questions of WMNST 604 “Gender, Culture, and Representation.” This incarnation of “Gender, Culture, and Representation” will take as its focus the relationships among gender, culture, power, and social change. Drawing upon theories of “gender,” “culture,” and “representation,” we’ll explore women’s cultural production as well as gendered and racialized strategies of cultural representation in contexts that range from the 18th-century Haitian Revolution to Hurricane Katrina and 9/11. The course begins by asking “how representation matters” through a case study of 9/11. Here we explore the role of representations of traumatic events in forging local, national, and transnational allegiances, and encounter gendered and racialized images that may serve as vehicles for competing narratives of “nation” and “community.” Next, we tackle the theoretical foundations of “gender, culture, and representation” through an interdisciplinary exploration of diverse modes of creative expression including film, oral traditions, dance, poetry, photography, painting, music, and political performance. How, we will ask, do various cultural performances or languages “speak” to particular audiences through gendered, racial, and sexual tropes? Feminist cultural theory broadens prior models of cultural experience by suggesting that all forms of culture condition, and are conditioned by, intersectional relations of power. In this unit, we will investigate feminist theories concerning cultural representation and appropriation, spectatorship and subjectivity, power and disempowerment, silence and voice. Next, we will apply these theoretical insights to a case study of Haiti, from its origins in revolution to the earthquake that decimated the country in January 2010. We will explore how particular representational practices signify “difference” and structure modes of “seeing” in ways that produce “knowledge” about the “other.” Through what gendered and racial tropes have culture producers within and outside of Haiti advanced, interpreted, and resisted social change? How have women and other marginalized groups challenged dominant representational regimes through their own forms of cultural production? 1 The last third of the course—co-created and taught by students in the class--will extend the theme of gender, culture and representation into students’ areas of interest and expertise. Drawing from gender history, cultural studies, feminist film and media studies, and feminist theories of performativity and visual culture, this course invites participants to become more sensitive readers of the gendered dynamics of cultural production and the global cultures in which we live. Learning Objectives: Develop a deeper understanding of the meanings of culture, and of how culture informs subjective experience; Learn to read the deployment of specific representations of gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, class, age, and sexuality as interventions in broader social and political debates; Deepen our knowledge of feminist cultural activism and of women as producers of culture; Cultivate an analytical approach to visual, oral, and performance cultures, including a sensitivity to silences and exclusions in different cultural genres; Develop a stronger grasp of cultural representation, cultural appropriation, and cultural activism and their relationship to gender, religion, sexuality, race, ethnicity, class, ablebodiedness, and nation. Create a classroom space for intellectual exploration, self-reflection and respectful listening across lines of difference and similarity. ASSIGNMENTS/GRADING Seminar Attendance and Participation (20% of grade) This advanced graduate seminar assumes your dedication, preparation, and engagement. It provides a unique opportunity, individually and collectively, to push ourselves to engage passionately, to listen deeply, to think creatively, to read and to write from the perspective of activists and intellectuals: producers rather than simply consumers of books and ideas. Graduate school may be one of the few times in life that we have the privilege to immerse ourselves in books, thought, and discussion. Each seminar is a potential celebration of the possibilities of collective exchange. The quality of our discussions depends upon each participant’s level of preparation. We will read several articles, or a book and an article each week. Students whose schedule cannot accommodate this reading load should consider a different class. Since informed, creative discussion is the essence of a seminar, and since each session will build upon those that came before, plan to arrive in seminar alive, engaged, and prepared to participate, with writing assignment in hand. Absences, including late arrivals or early departures, are disruptive to the learning community, and will affect your grade. Plan to arrive five minutes early rather than two minutes late. (Discuss any absolutely unavoidable absence with me in advance.) Careful notes on your reading, as well as your verbal comments, provide me with evidence of your preparation for class. Seminar Facilitation #1: (10% of grade) 2 All students will co-teach one seminar in the first ten weeks of class. Please look through the syllabus carefully and make a note of your top three choices. Seminar facilitators collaboratively: A) Develop a brief (10-minute) powerpoint presentation that provides background on the authors and contexts of that week’s reading. The powerpoint should also present an example from the visual or performing arts (music, dance, sculpture, painting), the media, or other forms of cultural production that illuminates some of the issues raised by the texts assigned that week. B) Develop a set of primary and subsidiary questions to guide the class through the seminar. Discuss these questions with the professor at least one week before the seminar, then email the revised version to classmates by Saturday night. Weekly Written Interventions and Questions: (20% of grade) Since writing challenges us to think clearly, each week there will be a short writing assignment (approximately two pages, double-spaced, times font, 12-point, 1” margins on all four sides) on the reading. Each assignment should accomplish three goals: A) summarize in one or two succinct sentences the most important contributions made by EACH assigned article or book to your understanding of gender, culture, and/or representation; B) develop your own reflections on the reading. These reflections may range from an exposition on the significance of the reading, to a critical review, to personal reflections that relate directly to the reading. C) Conclude with two interpretive questions that you would like to discuss in seminar. Written Review of Cultural Exhibition, Performance, Production (20% of grade) Attend and write a critical review of a cultural performance or exhibit in the SDSU or San Diego/Tijuana community that highlights cultural representations that focus upon women, gender, and/or sexuality. You may attend a museum exhibit, a dance or musical performance, a theatrical production, a spoken word performance, or a political event. The goal is to draw upon at least three class readings to open new theoretical perspectives on the performance or exhibition that you attended. The paper should be at least four pages, double-spaced, times font, 12-point, 1” margins on all four sides. Student-Designed Seminar, Paper, and Performance (30% of grade) In the tradition of feminist pedagogies, the last third of this course will be student designed and student led. After a class discussion in which students determine collectively the focus for the last four weeks, we will divide into small groups. Each group is responsible for designing and teaching one full class period. Each group will choose and acquire readings for the class (3-4 articles per class session), develop a class plan, devise discussion questions, and divide responsibilities for facilitation. Please meet with me (with all members present) at least once early in the planning process, and send me a class outline at least one full week prior to the presentation date for my feedback. Unlike the facilitation in the first 10 weeks, each student-designed session in the last four weeks of class will incorporate original performances/presentations, based on independent research. I strongly encourage those with an artistic bent to create and 3 present their own work (poetry, dance, fiction, visual arts, ritual), and to incorporate it into the presentation. Each presentation must include a creative component (an example drawn from the visual or performing arts, or from some form of women’s cultural production), and each must be accompanied by a research paper (at least ten pages, excluding bibliography; six pages if your project includes an original creative performance or piece of art). The paper is due on the date of the presentation. I will distribute further guidelines after students choose themes for those weeks. Meet with me as early as possible in the semester to discuss your paper. Performance length will vary depending upon the size of each group, but plan on approximately 10 minutes per person. The strongest performances are often collaborative, thus a three-person facilitation group would produce a collaborative performance of ½ hour. BLACKBOARD: Blackboard will be an essential method of communication in the class. Please check blackboard at least two or three times a week. Often I will post items during the week that need to be printed and brought to class. Alterations in the syllabus will also appear here. If you have any questions on how to access Blackboard, please check the Blackboard Help and Support website: http://its.sdsu.edu/bbsupport/. READINGS: You will find ALL of the required readings for the course on Blackboard in the Course Documents folder, posted under the appropriate week. The only exceptions are the following required texts, available for purchase at KB Books (5191 College Ave, 619-287-2665). We will also try to place copies of the texts below on Reserve at the SDSU library. Stuart Hall, ed., Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (Sage, UK, 1997) Leonora Sansay, Secret History: or, The Horrors of St. Domingue and Laura, ed. Michael J. Drexler (Broadview Editions:Petersborough, Ontario, 2007) Martin Munro, ed., Haiti Rising: Haitian History, Culture, and the Earthquake of 2010 (University of the West Indies Press: Mona, Kingston, Jamaica, 2010) Edwidge Danticat, Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work (Princeton:Princeton University Press, 2010) COURSE OUTLINE INTRODUCTION: IN THE EVENT—HOW REPRESENTATION MATTERS Week 1: August 29 Constructing the Nation: Domesticity, Race, and Representation READ: Morrison,“The Dead of September 11,” Ann Cvetkovich, “Trauma Ongoing,” and Marianne Hirsch, “I Took Pictures,” and Suheir Hammad, “first writing since,” in Trauma at Home: After 9/11, ed. by Judith Greenberg (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2003)” (don’t miss the link to Suheir Hammad’s spoken word performance—thanks to Kari Szakai: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fhWX2F6G7Y) 4 Inderpal Grewal, “Transnational America: Race, Gender and Citizenship after 9/11,” Social Identities 9/4 (2003): 535-561. UNIT I: FOUNDATIONS: THEORIZING GENDER, CULTURE, and REPRESENTATION Week 2: September 12 Cultural Studies and Feminist Cultural Theory (Since two weeks elapse between our first and second class meetings, plan to divide your time as follows: by Sept. 5, complete Stuart Hall on cultural studies, and by Sept. 12, complete the feminist cultural theorists.) READ: Stuart Hall, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices chap 1, The Work of Representation. Gloria Anzaldúa, “Haciendo Caras, una entrada,” introduction to Making Face, Making Soul. Recommended: Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic,” in Sister Outsider (1984). Anne Donadey with Françoise Lionnet, “Feminisms, Genders, Sexualities,” Introduction to Scholarship in Modern Languages and Literatures, ed. David G. Nicholls (New York: Modern Language Association, 2007), 225-244. Recommended: Suzanna Danuta Walters, “From Images of Women to Woman as Image,” Material Girls: Making Sense of Feminist Cultural Theory (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995). Week 3: September 19 Viewing Positions: Gender, Visual Culture, and Feminist Film Theory In class screen John Berger, “Ways of Seeing” READ: Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”; bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators”; and Judith Halberstam “The Transgender Look” in Gender and Visual Culture Jane Gaines, “White Privilege and Looking Relations: Race and Gender in Feminist Film Theory” Kobena Mercer, “Reading racial fetishism: the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe,” in Visual Cultures: A Reader Week 4: September 26 Corporeal Performance: Music and Dance READ: Susan Leigh Foster, Choreographing Empathy (excerpts) Judy Kutulas, “’You Probably Think This Song is About You’: 1970s Women’s Music from Carole King to the Disco Divas,” in Disco Divas: Women and Popular Culture in the 1970s, ed. Sherrie A. Inness (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003) pp. 172-194. Alice Echols, Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture (NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010), chaps. 2-3 Week 5: October 3 Artistic Encounters 5 READ: Griselda Pollock, “Differencing: Feminism’s encounter with the canon,” in Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s History (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 23-38. Gloria Anzaldua, “La conciencia de la mestiza—Towards a New Consciousness,” and “To Live in the Borderlands means...,” in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, pp. 99-113, 216-217 Laura E. Pérez, Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities. Duke University Press, 2007, pp. 1-16, 257-296. October 5: SDSU Women's Studies Department--Day of Action: The Effects of Budget Cuts on Women. See https://www.facebook.com/dayofactionsdsu Week 6: October 10 Cultural Performance, Political Protest, and The Spectacle of Violence: Katrina and its Legacies READ: Emmanuel David, “Cultural Trauma, Memory, and Gendered Collective Action: The Case of ‘Women of the Storm’ Following Hurricane Katrina,” NWSA Journal (2008): 138-162 Rachel Luft, “Looking for Common Ground: Relief Work in Post-Katrina New Orleans as an American Parable of Race and Gender Violence, ” NWSA Journal (2008) Stuart Hall, chap 4 “The Spectacle of the ‘Other’” in your textbook, Representation In class SCREEN: clips from Spike Lee, “When the Levees Broke” (documentary 2007) In class VIEW: graphic art of Kara Walker, After the Deluge UNIT 2: CONTEXTS: SPOTLIGHT ON HAITI Week 7: October 17 Representations of Revolution: Heroes and Villains Marlene Riaud Apollon, “When They Write History,” and “Blood-Sun” in I Want to Dance (Baltimore: American Literary Press, 1996), pp. 33-35. Doris Garraway, “Race, Reproduction and Family Romance in Saint-Domingue,” in The Libertine Colony, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), pp. 240-292. David Geggus, chap. 1, “The Haitian Revolution,” in Haitian Revolutionary Studies (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), pp. 5-29. Elizabeth Colwill, “Bearing Witness to Freedom” Week 8: Oct. 24 Silencing the Past Leonora Sansay, Secret History: or, The Horrors of St. Domingo, and Laura Week 9: October 31 Reclamation: Writing, Ritual, and Resistance Edwidge Danticat, Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work Marlene Rigaud Apollon, “We Were Never Young,” in I Want to Dance, pp. 6-7 6 Claudine Michel, “Vodou in Haiti: Way of Life and Mode of Survival,” in Invisible Powers: Vodou in Haitian Life and Culture (NY: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006), pp. 27-37. In class VIEW: art of Eduard Duval Carrié Week 10: November 7 Representation and Self-Presentation: Who Speaks for Whom? Martin Munro, ed., Haiti Rising: Haitian History, Culture, and the Earthquake of 2010 (University of the West Indies Press: Mona, Kingston, Jamaica, 2010) Screen: Updates from “Poto Mitan” APPLICATIONS (Student Created) November 14 November 21 November 28 December 5 7 CLASS POLICIES: Technology I check email every evening. It may take me one or two days to get back to you, depending upon my schedule. I do not answer work-related emails on the weekends, in the belief that it is important for us to create and to model for one another a world in which there is some harbor from technology and space for other aspects of our lives. Please, no cell phones or laptops in class, unless specifically required for a presentation. ______________________________________________________________________ Regarding Students with special needs Students who need accommodation of disabilities should contact me privately to discuss specific accommodations for which they have received authorization. If you have a disability, but have not contacted Student Disability Services at 619-594-6473 (Calpulli Center, Third Floor, Suite 3101), please do so before making an appointment to see me. _______________________________________________________________________ Regarding Plagiarism Cheating and plagiarism are serious offenses. You are plagiarizing or cheating if you: For written work, copy anything from a book, article or website and add or paste it into your paper without using quotation marks and/or without providing the full reference for the quotation, including page number For written work, summarize / paraphrase in your own words ideas you got from a book, article, or the web without providing the full reference for the source (including page number in the humanities) For an oral presentation, copy anything from a book, article, or website and present it orally as if it were your own words. You must summarize and paraphrase in your own words, and bring a list of references in case the professor asks to see it Use visuals or graphs you got from a book, article, or website without providing the full reference for the picture or table Recycle a paper you wrote for another class Turn in the same (or a very similar paper) for two classes Purchase or otherwise obtain a paper and turn it in as your own work Copy off of a classmate Use technology or smuggle in documents to obtain or check information in an exam situation In a research paper, it is always better to include too many references than not enough. When in doubt, always err on the side of caution. If you have too many references it might make your professor smile; if you don’t have enough you might be suspected of plagiarism. If you have any question or uncertainty about what is or is not cheating, it is your responsibility to ask your instructor. 8 Consequences of cheating and plagiarism Consequences are at the instructor’s and the Judicial Procedures Office’s discretion. Instructors are mandated by the CSU system to report the offense to the Judicial Procedures Office. Consequences may include any of the following: failing the assignment failing the class warning probation suspension expulsion For more detailed information, read the chapter on plagiarism in the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (6th edition, 2003); visit the following website http://www.indiana.edu/~wts/pamphlets/plagiarism.shtml and talk to your professors before turning in your paper or doing your oral presentation if anything remains unclear. The University of Indiana has very helpful writing hints for students, including some on how to cite sources. Please visit http://www.indiana.edu/~wts/pamphlets.shtml for more information. 9

![CTLR Seminar Promo: 10march14 [DOC 142.50KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007541889_2-e867530a05de7f49f646a0a26ad268ab-300x300.png)