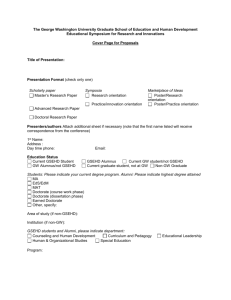

Understandings of Pedagogical Practice in Doctorates of Education

advertisement

Understandings of Pedagogical Practice in Doctorates of Education Dr Alexis Taylor Brunel University Abstract How teaching is experienced by university teachers in relation to Professional Doctorate Education has been under-explored. The paper presents the findings of a small-scale study supported by ESCalate funding concerning the identification of pedagogical practice in Doctorates of Education and the consequences of this for the student learning experience. Introduction This paper contributes to the Higher Education Annual Conference of Transforming the Student Experience and is located within the theme of Learning and Teaching. The session comprises an overview of the project and the presentation of the findings to date with time allocated for questions and audience commentary. The session is supported by this paper, which forms the basis of the final report to ESCalate and a subsequent article submission to an internationalreferred journal. The paper explores how university teachers involved in Doctorates of Education experience teaching, how this informs pedagogical practices undertaken and the consequences of this for the student learning experience. Overview of Professional Doctorates Over the last decade or so doctoral education in the U.K. has undergone a transformation, resulting in new routes, including, the new route PhD and doctorates by publication. Three external drivers for this can be identified. Firstly, an apparent dissatisfaction by government with arrangements for research training of the traditional PhD. Identified issues included the length of time PhD students took to complete, low completion rates, and the narrowness rather than depth of research training, raising questions about the lack of transferable skills into employment (Park, 2007). Secondly, a changing context for universities. In line with an international move in higher education universities in the U.K. have become part of the globalised knowledge market (Tennant, 2004; Usher, 2002) bringing an increasing emphasis on context-specific and problem-oriented knowledge creation. Consequently, this changing view of knowledge has encouraged universities to develop new provision for a range of emerging external partners. Thirdly, an enhancement of the professions has led to a consequent emphasis on higher level professional training and continuing professional development of practitioners. (For example, in relation to statutory education, it is a priority of the Government that within 5 years all those in the teaching profession will have at least a Masters qualification : DfCSF, 2007). This will impact in the long term on recruitment to the Doctorate of Education). July 2008 1 It was anticipated that the professional doctorate would address some of these issues, and, thus, the external context has provided a good opportunity for the growth of professional doctorates. As part of this changing picture professional doctorates have grown rapidly in the U.K. since the 1990s over a wide range of disciplines (UKCGE, 2002). The aim of professional doctorates is to develop the high level skills (usually senior) professionals need to deal with ‘real world problems’ (Robson, 2002) emanating from their own professional practice and contexts. As such this provides one clear way (among others : see Fink, 2006) in which the professional doctorate differs from the traditional PhD research degree - by moving beyond making a new contribution to knowledge to making a difference to professionals and professional. The professional doctorate which forms the focus of this project - Doctorate of Education (EdD) - has the largest market (UKCGE, 2002). Presently in the U.K. Doctorates of Education are generally structured into a two-stage model. Stage 1 ‘Research Training’ Element (commonly known as the ‘taught’ element) taught by teaching teams to annual cohort of students, assessed through individual pieces of coursework and followed by Stage 2 an individual Research-Based Thesis undertaken with the support of two supervisors and assessed through the production of thesis and oral examination with external and internal examiners. The Literature There is a dearth of literature concerning professional doctorates, which, given their relative newness, is understandable. In the U.K. the growth of literature has been less quick than in other counties where they have grown in the same time-span as the U.K. (In Australia, for example, with the work of Malfroy, 2005; Malfroy and Yates, 2003; Maxwell, 2003; Neumann, 2002). In the U.K. studies to date have dealt with a number of separate areas. Thorne and Francis (2001) compared the traditional and professional doctorates and found that government recommendations for doctoral study took an homogeneous rather than a heterogeneous approach, especially in relation to students’ career positions. Doncaster and Lester (2002) explored the notion and development of capability with reference to a generic work-based professional doctorate. The nature of the impact of professional knowledge in the subjects of business, education and engineering was explored by Scott, Brown, Lunt and Thorne, (2004). Leonard, Coate and Becker (2004) examined the continuing professional and career development of doctoral students including those on professional programmes. Bourner, Bowden and Laing (2001) explored structural and developmental features although Lunt’s work (2002) suggested there was confusion about the aims and mission of professional doctorates. Heath’s study (2006) supported this by concluding that that variation in how Doctorates of July 2008 2 Education are constructed relates to different values placed on knowledge which affects matters such as supervision. No studies have been found, however, which explicitly explore pedagogy in relation to professional doctorates. In particular, what is understood about pedagogy by university teachers working on Doctorates of Education has been under-explored. The project contributes to this gap. Approach The project was designed within a phenomenological and descriptive/interpretive paradigm. The project occurred in 3 on-going Stages. Stage 1 comprised a contextual background and extensive literature search and review and Stage 2 was a search and analysis of publicly available documentation and web-sites of a number of Doctorates of Education. Stage 3 was a micro-level investigation in a small number of institutions with contrasting characteristics and contexts and different approaches to the Doctorate of Education. Relevant documentation relating to the specific Doctorate of Education programmes (for example, handbooks) was collected and semi-structured interviews were undertaken with programme leaders and university teachers working on the Doctorate of Education. Each interview had key focusing questions : the structure and organisation of the Doctorate of Education as a whole, including the content of, and approach to, the Research Training Element; university teachers’ experience of working on the Doctorate of Education; what university teachers think helps a student on the Doctorate of Education to learn to become a ‘researching professional’ (Bourner, Katz and Watson, 2000); and university teachers’ understanding of what learning to research meant to them. The analysis of the interview transcripts was supported by information gleamed from Stage 1 and Stage 2, and aimed to identify generalised opinion on the part of the university lecturers as a group and so the interview transcripts were analysed as a complete data set through an iterative process using an open-coding framework. The analysis showed 2 broad approaches to pedagogy labelled as Acquisition and Holistic Development. Acquisition Teaching Here, teaching concentrates on information about research and the skills and craft of undertaking research. Information from a conceptual and/or empirical perspective about research studies (especially if it links to university teachers’ areas of expertise) is transmitted to students. This equates with ‘knowledge’ about research and its outcomes. Teaching also focuses on giving practical knowledge of research techniques and developing an July 2008 3 understanding of the process by which knowledge is generated; that is, on developing and constructing the knowledge of how to do research. As university teacher 4 said, I think they learn partly from our taught sessions. They get a range of principle research methodologies presented to them [which] seems to be quite important really because [of] giving them common taught or common experience Organisation of Teaching The teaching programme is usually organised according to individual sessions linked to themes and according to the areas of expertise of individual university teachers/researchers (internal and external to the university). The ‘taught’ element is treated as preparation for the end product of the research thesis. The university appears to take central place as the site for the teaching and the professional setting is perceived as where students implement and demonstrate the application of the knowledge they acquire at university. The making of connections with the professional context and practice is left up to students through the process of application, although beyond this, research and professional practice are not deliberately connected to an obvious degree. Professional practice is seen as busy and pragmatic and the research training at the university provides the benefit of distance from that practice. This is summed up by university teacher 6 who said, All the time it’s this tension between giving them information but at the same time insisting this is your doctorate… Teaching Activities Preference is for teaching to be presented in an organized and structured way through individual lecturers. Usual activities include the use of PowerPoint, students taking notes and listening in class and asking questions. The university sessions are supplemented by directed reading and structured activities to be carried out between sessions in students’ professional setting which develop these skills in action. Feedback and guidance on students’ research activities are provided through individual tutorials with specified supervisors who are experts in the subject of students’ research area, and who may, or may not be, involved in the teaching programme. Group tutorials and workshops are included as well as individual sessions with supervisors. Holistic Development Teaching Teaching focuses on critical consideration about the principles and practice of, and also critical engagement with, generic professional practices and generic research methods; that is, on educational issues, on research on these, as well as on developing students’ competence to use and do research. The focus is on knowledge that is created and used by practitioners in the context of their own personal professional practice. In this way knowledge is viewed as contextual and research as the vehicle by which this contextual knowledge is July 2008 4 constructed. Moreover there is a critical consideration within the teaching about what students ‘say’ about their learning about and through research. Teaching includes critical consideration of the complexity students experience as they progress through the Doctorate of Education and as they try to make sense of their changing identity. Teaching provides variation to students to develop conceptually, and thus, change themselves. Thus, as university teacher 7 said, …it’s deeply about identities professional and practitioners rather than another identity or looking for a gap in the literature, or looking at a particular issue. Organisation of Teaching The teaching is usually planned by a core team with dedicated responsibility for the programme as a whole. The planning takes account of connections within the programme - for example, between the research training element and the thesis, between the ‘taught’ element and assessments, between what the students are ‘taught’ and the research students undertake in their workplace and between the university teaching and the professional context. Process and product facilitate each other. The focus is on the interaction between teaching and learning, and the inter-personal relationship between university teacher(s) and the student (s). Teaching Activities This process of development is deliberately included into the teaching strategies, most obviously seen in the content of the formal teaching curriculum, teaching techniques and coursework assessments. The content of the ‘taught’ element is clearly connected between sessions by teachers, and also in planned directed study activities. Teaching activities are underpinned by what students have to say. For example, critical engagement with research literature, asking students to bring in research studies they had found themselves for extended discussion with peers and university teachers, group tutorials and on-line discussion. Deliberately built into the formal teaching sessions are student presentations of their inquiry work and subsequent peer discussion. Students are also encouraged to take initiative - for example, setting up student workshops on their own (individual and group) research. Importantly, evaluations by students of their own learning (beyond course evaluations) are used routinely so that students consider critically how they are developing professionally and personally as they learn about research, how to do research and as they undertake research in their professional context. Coursework also includes developmental reflective activities. Interim workshops between the formal taught sessions and between the different stages of the thesis are planned into the programme. This keeps the ‘cohort’ feel to the programme (albeit with a changing cohort) but also focuses on student change throughout the duration of the programme. July 2008 5 Discussion One factor underlying the two different approaches towards pedagogy in this present study is the variety of ways in which teaching is understood and approached. A number of international research studies (for example, Samuelowicz and Bain, 2001; Akerkind, 2004) show that university teachers have qualitatively different conceptions of teaching. These range through imparting information, transmitting structured knowledge, student-teacher interaction, facilitating understanding and conceptual change and changing as a person. The last category is usually advocated as the ultimate aim of higher education. Scholars (e.g. Prosser and Trigwell, 1999) have also found an empirical relationship between university teachers’ views of teaching and students’ learning, in which a more complex view of teaching is regarded as producing high quality learning outcomes among students where learning is seen as a gradual process of deepening understanding of the connections between various concepts and transference to new contexts. In this present project this range is evident. The imparting of information, the transmission of structured knowledge, and student-teacher interaction can be seen in Acquisition and facilitating understanding, conceptual change and changing as a person can be identified in Holistic Development. It could be argued that the 2 different approaches identified in this present study demonstrate a simple and a more complex understanding of pedagogy for Doctorates of Education. However, this was a small-scale project and care must be taken not to claim too much. It is possible that further approaches can be discerned; for example, Acquisition might be separated into ‘pedagogy orientated by knowledge about research’ and ‘pedagogy orientated by knowledge about how to do research’. Further analysis is being undertaken to see if this holds. Another important factor underlying the two different approaches towards pedagogy in this present study is the consequences for student learning and its outcomes. In Acquisition the aims for student learning appears 2-fold. Firstly, students learn to know what ‘research’ ‘looks like’. Consequently students are kept up-to-date about what research is occurring and what it is saying. Secondly, students learn to understand the research process so that they develop competence about using research and about doing research. As a result of both of these, students learn how to research themselves and how to use the research strategies to undertake research in their own professional context. The doctoral qualification is seen as an important outcome in its own right and the emphasis is on the completion of each student’s personal and individual research, which is seen as an academic undertaking by the individual student and demonstrated through the thesis, viva and award. July 2008 6 Holistic Development appears in contrast. Again, the aim for student learning appears 2-fold. Students learn to ‘do research’, which is seen as an intervention, undertaken for the specific purpose of understanding and improving students’ own professional practice in students’ own professional contexts. Firstly, the transactional nature of the Doctorate of Education is evident; that is, to enable students to “do things better” in their professional setting, to reflect on their individual practice and to try out alternatives. Secondly, students learn to develop professionally, but also personally, and to acknowledge their changing identity as they progress through the Doctorate of Education; thus, the transformational nature of the Doctorate of Education. The experience of the Doctorate of Education assists in articulating and developing previously held tacit knowledge and thinking to a high level around the chosen area of research. The emphasise is on the process of construction of the student as a ‘researching professional’; that is, having increased confidence in their own thoughts and decisions, and of being able to understand the alternative viewpoints of others; of taking the initiative with their research; of being able to work in different ways with different people; and of transferring their learning as researching professionals into different contexts; and in doing all this establishing for themselves a new identity. The Doctorate of Education is viewed as successful if it has resulted in the obtaining of the qualification, but, moreover, for its transformative impact. Essentially, then in Acquisition the focus is on the university teacher, what is to be taught and the tangible outcome of the doctoral qualification; and in Holistic Development, the focus of teaching is the student, and how the process of teaching develops students holistically as individuals as well as the tangible outcome of the doctoral qualification. Two issues are raised. Firstly, the Acquisition approach might imply that the traditional PhD concept of doctoral enterprise as the production of the ‘independent, autonomous scholars’ as opposed to the ‘holistically developed practitioner’ still continues. In turn, this raises the question of what is the essential distinctiveness of Doctorates of Education. Effectively, whether the focus of the Doctorate of Education is on the product (thesis) of work or the process of the work (Park, 2007). What the two approaches identified in this present project show is that Doctorates of Education are valued for their transformative - as well as transactional and transmission – capacity. Essentially, transformation involving moving beyond a set of knowledge and skills (seen in Acquisition) to promoting learning (as Holistic Development). What is advocated here is that – as well as learning about and how to use research and undertaking research pedagogy should focus on teaching which enables students to make sense of the process of change as they develop a new identity as a researching professional; that is, a clear-cut July 2008 7 pedagogic philosophy which takes a ‘student- learning focus’ (Prosser and Trigwell, 1999) or moving beyond ‘knowing that’ or ‘knowing how’ into what Hagar (2004) calls ‘organic…wholeperson nature of learning’. (Wood’s study (2000) with Doctorate of Education students also supports this notion when it found that learning to research was congruent with learning as related to a change in one’s own person). This underlines the need to reflect critically on the pedagogical rationale underpinning Doctorates of Education and to treat pedagogy as problematic. Some questions this might raise are : how is the student learning experience understood and approached ? what are some of the key experiences that promote and support an holistic developmental approach to student learning ? how is teaching and the teaching context organised to develop an holistic developmental approach to student learning ? what are the implications for the structure of the programme and teaching methods ? what counts as ‘curriculum’ for Doctorates of Education ? what does the ‘taught element’ mean to those who are working on the programme ? what are the implications for research supervision arrangements, assessment and the vive voce examination ? Implications Two implications are identified. Firstly, for the present structural arrangements for Doctorates of Education. The present two-stage structure indicates a number of ‘separations’, which bring both a conceptual and practical confusion about the pedagogical philosophy underpinning the Doctorate of Education. The Research Training (or ‘taught’) element appears as a separate stream in preparation for the research element. This two-stage structure necessitates a separation of assessment - between the assessment for ‘taught element’ (through separate pieces of coursework or compilation into a portfolio) and assessment for the ‘research’ element (through traditional viva), where the successful assessment of the ‘taught’ element normally acts as a progression to the Stage 2. In consequence this brings a separation also between external examiners for each element, and raises the issues of where the learning outcomes for the whole programme are demonstrated and assessed. This has a consequence of possible separations of Doctorate of Education teams into those involved in either the ‘taught’ element or those involved in the ‘research’ element; that is between those involved in ‘teaching’ and those involved in ‘supervision’. July 2008 8 This leads to the second implication, which is for arrangements for developmental activities for those involved in Doctorates of Education. A ‘learning on the job’ approach may not be sufficient and staff development might be best served by proactive deliberate management of induction and in-service activities. This would mean the setting up of development activities where : the different starting points of members of the teaching team in terms of qualifications, experience, and professional expertise were taken into consideration. For example, do those who have come through the Doctorate of Education route (of whom there is a growing number) differ in their approach to teaching to those that have come through the PhD route ? Do those who are recognised as ‘expert researchers’ in their institutions have a different approach to pedagogy on the Doctorate of Education to those who are considered ‘expert teachers’ ? implicit theories that are held about the Doctorate of Education and the critical aspects of pedagogy can be confronted; and differences in understandings can be managed effectively so that tensions and any discrepancies in pedagogical philosophy and practice can be negotiated. Underlying such staff development is the principle that university teachers as individuals and teams are learners as well as teachers. In this way understanding of student learning and thinking about the pedagogy that underpins this will be enhanced. Conclusion It must be emphasised that this was a small-scale project and no generalisations can be claimed. The descriptions above must remain provisional and further work is necessary. For example, an in-depth prospective study involving a number of different data collection methods with Doctorate of Education teams working in different single contexts will be useful to see whether the findings identified in this present study stand up. However, the ‘framework’ identified above may be useful to those working on Doctorates of Education (and other professional doctorates) in different contexts and who are also thinking about pedagogical practices which might contribute to student learning. This project has shown that the Doctorate of Education is a significant educational undertaking; and, thus, there is a need for the pedagogical aspects to be considered more overtly. Teaching does not automatically ‘turn into’ student learning. University teachers and teams of university teachers July 2008 9 are at the heart of this reflection. This study has made a small start to acknowledging the complexity of this issue. References Akerkind, G. (2004) A new dimension to understanding university teaching, Teaching in Higher Education, 9, 3, 363-375 Bourner, T. Katz, T. and Watson, D. (2000) Professional doctorates : the development of researching professionals in Bourner, T. et al New Directions in Professional Higher Education SRHE Buckingham Bourner, T., Bowden, R. and Laing, S. (2001) Professional doctorates in England Studies in Higher Education 26, 1, 65-83. DFCSF (2007) The Children’s Plan TSO London Doncaster, K. and Lester, S (2002) Capability and its development experience from a workbased doctorate Studies in Higher Education 27, 1, 91-100 Fink, D. (2006) The professional doctorate : its relativity to the PhD and relevance for the knowledge economy International Journal of Doctoral Studies 1, 1, 35-44 Hager, P. (2004) Conceptions of learning and understanding learning at work Studies in Continuing Education 26, 1, 3-17 Heath, H. (2006) Supervision of professional doctorates : education doctorates in English universities Higher Education Review 38, 2, 21-39 Lunt, I. (2002) Professional Doctorates UKCGE London Malfroy, J. (2005) Doctoral supervision, workplace research and changing pedagogic practices Higher Education Research and Development 24, 2, 165-178 Malfroy, J. and Yates, L. (2003) Knowledge in action : doctoral programmes forging new identities Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 25, 2, 119-129 Maxwell, T. (2003) From first to second generation professional doctorate Studies in Higher Education 28, 3, 279-291 Neumann, R. (2002) Doctoral differences : Professional doctorates and PhDs compared Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 27, 2, 173-188 Park, C. (2007) Refining the Doctorate : Discussion Paper The Higher Education Academy Prosser, M. and Trigwell, K. (1999) Understanding Teaching and Learning : The Experience in Higher Education (Buckingham The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press) Robson, C. (2002) Real World Research Blackwell Oxford Samuelowicz, J. and Bain, J (2001) Revisiting academics’ beliefs about teaching and learning, Higher Education, 41, 299-395 July 2008 10 Scott, D.; Brown, A., Lunt, I. and Thorne, L. (2004) Professional Doctorates : Integrating professional and academic knowledge SRHE and OU England Tennant, M. (2004) Doctoring the knowledge worker Studies in Continuing Higher Education 26, 3, 431-441 Thorne, I. and Francis, J. (2001) PhD and professional doctorate experience : the problematics of the National Qualifications Framework Higher Education Review 33, 3, 13-29 UKCGE (2002) Report on Professional Doctorates UKCGE Dudley Usher, R. (2002) A diversity of doctorates : fitness for the knowledge economy Higher Education Research and Development 21, 2, 143-153 Wood, K. (2000) The experience of learning to teach : Changing student teachers’ ways of understanding teaching, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 32, 1, 75-93 July 2008 11