18th September 2011 SERMON: “It`s Not Fair

advertisement

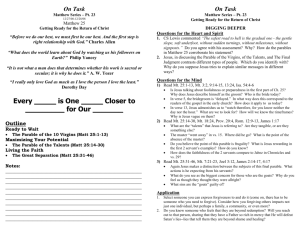

18th September 2011 SERMON: “It’s Not Fair!” by Allister Lane Matthew 20:1-16 Romans 12:1-8 As we have been following the lectionary readings through Matthew’s Gospel we have reflected on the teaching of Jesus, particularly on his teaching on the nature of the Kingdom of God; this new reality he has come to bring. In his teaching, we hear Jesus regularly use parables – short pithy stories that take recognisable, everyday situations and infuse them with unexpected twists to reveal something about God’s new reality. The parable of Jesus we’ve heard today is set in the situation of a business and employment relations. Unlike some biblical illustrations, this situation of employment and remuneration is just as understandable and relevant today as it would have been for those who first heard Jesus tell this parable. In the same way, the aspects that offended those who first heard this parable are likely to be the same aspects that offend audiences today. Take a look in your Order of Service at the next hymn we will sing ‘Jerusalem’. In the last line of the first verse William Blake poses the question: And was Jerusalem builded here Among these dark satanic mills? Do you know what he is referring to when he says ‘these dark satanic mills’? Blake wrote these words in the very early stages of the Industrial Revolution. What he saw, he felt brought destruction of nature and human relationships. Blake lived a short distance from the Albion Flour Mills, which was the first major factory in London. He regarded it the work of the Devil, with a physically and spiritually repressive ideology based on a quantifiable reality. He saw the emerging mills as the primary mechanism for the enslavement of (potentially) millions. As troubling as an emerging economy driven by mass-production is for Blake (or a sophisticated economy where an individual can perpetrate massive corporate banking fraud is for us...) this parable of Jesus’ is not teaching about employment policy or corporate economics. Thomas Long identifies that, “the purpose of this parable is not to provide a practical guide for management of a vineyard [or other business]. Indeed, the aim of this parable is to be monumentally impractical, to fracture so thoroughly our expectations, our customary patterns of practicality, that we are forced to think new thoughts – new thoughts about ourselves, about other people, and about God.” Jesus’ parable focuses on the peculiar sense of fairness demonstrated by the landowner. At the beginning of the day, he hires some labourers to work in his vineyard for what is considered a usual day’s wage. He returns again to the marketplace at nine o’clock and discovers others standing idle. He sends them into his vineyard with the promise he will pay them what is ‘right’. He returns again at noon, and at three o’clock, and again sends workers to his vineyard. Finally, he returns about five o’clock (only about an hour before sunset). This time he asks these workers why they have been standing idle all day. Their response “Because no one has hired us.” sounds lame, but reflects the dependence of such workers. The landowner said to them, “You also go into the vineyard.” The landowner calls together all the workers at evening. Strangely enough, those hired last are paid first. And it is this reversal of the expected order of payment (together with the equal payments) that creates the tension in the story. When those who were hired at the end of the day receive a full daily wage, those who worked the full day expect more. When they are paid the same daily wage they grumbled against the landowner. Listen again how they express their resentment: “These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us” We’ll come back to this particular complaint later, but for now we must recognise that what we hear through this parable is that God’s grace is unfair. And we know this is precisely Jesus’ point, because the beginning of the parable begins with a key word “For...” This opening word “For...” links the parable with what was happening in the previous chapter. And what was that? The previous chapter involved discussion about children... and eunuchs... and rich men, and Jesus concluded his conversations with the same words he concluded this parable with: “the last will be first, and the first will be last.” Hear this point: In the Kingdom of God there can be no assumption about spiritual status. The prevailing culture (then as now) lives by “Might is right”; “To the victor go the spoils”; even “you do the crime, you do the time”. Certainly not “the last will be first, and the first will be last.” God's justice reaches out to include the least, the last, the little ones, the children, the poor, the weak, and the suffering. The landowner doesn’t leave those left behind in the market-place. Even though he’s not going to get much work from them (for it is late in the day) he doesn’t leave them there, he includes them in the activity “You also go into the vineyard.” This divine landowner includes those the world ignores and rejects in the activity of the Kingdom. Like those not picked for the team, left standing in the playground, the gracious call is “I can use you. Let’s go.” God's justice consists of forgiving debts, restoring relationships, and making the creation whole. Justice ordered around "merit" or differentiation of status, on the other hand, preserves a world of division and alienation. If God does act as the landowner has, then the parable points to the radical, disruptive, even offensive character of God's free and unmerited grace toward humankind. The problem with such grace (as we heard in the resentful accusation of the workers earlier) is that grace "makes them equal to us," whoever "they" might be in our various systems of differentiation. Throughout history, Christians have often functioned in ways that confirm and preserve differences, whether economic, social, spiritual, or racial. This is precisely what the parable subverts; any criteria by which we might represent ourselves before God as "the first ones." In the end, there is no first and last, righteous and unrighteous, Jew or Gentile, Protestant or Catholic, adult or child in God's Kingdom; for all stand before God on the basis of the same grace, all called to work in the same vineyard, together producing its fruit. Jesus teaches about the new reality of God’s Kingdom. And God’s Kingdom introduces a new economy and a new identity. This new reality is one where we get what we DON’T deserve. This new reality is what we celebrate in Baptism – Alice hasn’t ‘earned’ God’s love and forgiveness, any more than the rest of us. Jesus is teaching us two very obvious things: 1. that God’s grace is abundant, and 2. that we are not to resent God’s grace. Philip Yancey (author of ‘What’s so Amazing About Grace?’) acknowledges the grace of God is presented in this parable is not fair, but asks how this understanding of God might affect our response to God. Will we be less devoted to a gracious God like this? After all, such grace means we can neglect any devotion and service of God and still receive the rewards of God’s grace. Yancey says that if we truly understand this sort of grace, from this sort of God, we won’t want to ‘get away with what we can’, we’ll want to be as connected as we can to God and share in this grace as much as we can. God’s grace helps us see the nature of God’s new reality. Our experiences of transactional economic systems that permeate so many of our relationships (reducing our identities to mere commodities) can be rejected for the true ways of God. It does require an act of will on our part however. Accepting God’s grace means consciously rejecting the world’s un-grace. And the discernment of what is truly God’s ways requires intentionality on our part; allowing our intellect to function and to grow in compliment to our spirits. Or as Paul puts it in the letter to the Romans “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect.” (12:2) Commenting on Jesus’ parable again, Thomas Long observes that the first-hour workers, even though they don't recognise it, are also given grace: a day's wage, the sustenance of life. But grace is not their framework. They are bargainers, contract workers. They think that life works according to deals, and negotiations; they even strike bargains with the Almighty. They count up good deeds, check their time cards, and divvy out their devotion with measuring spoons. Their vocabulary is filled with cries of "I deserve" and "where's mine?" and "it is my God-given right." The contrast could not be greater. The latecomers never discussed payment; they are working for the landowner, for God. The bargainers are working for a denarius. Both get what they are working for. And so we see the stark poverty of the first-hour workers. Everybody in the parable is offered the wealth of the kingdom; the deep river of providence flows through everybody's life. God gives everyone a daily wage so extravagant that no one could ever spend it all. A deluge of grace descends on all; torrents of joy and blessing fall everywhere. And there these first-hour workers stand, drenched in God's mercy, an ocean of grace running down their faces, clutching their little contracts and whining that they deserve more rain. When the landowner says to the first-hour workers, "Are you envious because I am generous?" he is really saying, "Does my generosity expose the poverty of your own spirit?" Indeed, this is a major theological theme in Matthew. In Jesus, the world sees the generosity of God, and everything depends upon how the human spirit responds to this divine display of good will. Perhaps through all of Jesus’ teaching it is in this parable, ironically, that we are presented with the most challenging and offensive word of all: God is generous. God's generosity spills over the stop-banks we have built to contain it and surges mercifully over the landscape of human life. The rush of God's generosity bears away in its flood every rickety shack built on human schemes of merit and this world's view of fairness. Whose will can match the mercy of God? Finally, only one human being was capable of that - Jesus. "Worthy is the Lamb that was slain. . . ." Worthy is Jesus, the Son of God who shares with us (with all of us) what is his. AMEN.