Is performing a chest X-ray during pregnancy considered harmful to

advertisement

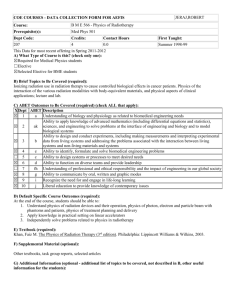

Amaris K. Balitsky Is performing a chest X-ray during pregnancy considered harmful to the fetus? Amaris K Balitsky1, MSc., Meldon Kahan, MD1,2 Daphne Williams, MD1,2 1. University of Toronto, Faculty of Medicine, 1 King’s College Circle, Toronto, Ontario 2. St. Joseph’s Health Centre, Family Medicine/Urban Family Health Team, 30 The Queensway, Toronto, Ontario Correspondence: amaris.balitsky@utoronto.ca UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 1 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky ABSTRACT Objective: To evaluate the literature on the safety of performing chest X-rays during pregnancy. Methodology: An Ovid MEDLINE search (from 1967 to present) was performed using MeSH headings, as listed below. The search was limited to the English language and human studies. Results: The search yielded 23 articles. Eight articles were selected. Those not selected included articles about radiation pre-conception, infants exposed to radiation, or total body radiation. Earlier studies from the 1980’s, showed increased risk of childhood cancers in children who were exposed to ionized radiation during pregnancy. These studies included radiation to the abdomen as part of intrauterine diagnosis. Two reviews revealed that there is no increased risk of congenital malformation, intrauterine growth retardation, or abortion from low-dose radiation to the fetus. Maximal risk of 1 rad is 0.003%, which is thousands of times smaller than spontaneous rates of the above fetal complications. In a study evaluating prenatal X-ray exposure and rhabdomyosarcoma in children, although there was increased risk in dental X-rays in first and third trimester, there was no specific increased risk of chest or abdominal X-rays. In a study on teratogen risk of radiation, it was found that fetal doses given to head, neck, chest and extremities are extremely low (<.01 rad) because of the low maternal radiation dose and distance from fetus. Conclusion: These studies indicate that ionized radiation to the chest during pregnancy is safe for the fetus in regards to fetal and childhood well-being. KEYWORDS: pregnancy, X-ray, fetal abnormality UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 2 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky INTRODUCTION A case: A G3P0 28 year old previously healthy female, presented to the family medicine clinic for her regular prenatal visit at 28+3weeks. She was recently diagnosed with gestational diabetes, which was effectively controlled with diet. Otherwise, she had no other pregnancy related complications. As the uneventful visit was wrapping up, the patient exclaimed, “Oh yeah, I have been spitting up some blood.” The patient had been to the emergency department two days prior to investigate this new symptom. The emergency physician decided against a chest X-ray given the “risks to the fetus.” If this patient were not pregnant and had presented to the ED with hemoptysis, there would be no hesitation in performing a chest X-ray, in order to necessarily rule out dangerous and possibly fatal outcomes such as pulmonary embolism. This case was one out of three occurrences in this physician’s family medicine practice, where physicians hesitated, albeit with a perceived best interest of the patient in mind, and failed to perform the appropriate investigations in a pregnant woman for fear of poor fetal outcomes. A missed or delayed diagnosis can possibly pose a greater risk to a woman and the fetus than the effects of ionized radiation. Table 1 highlights the average fetal doses of radiation from various X-ray procedures. According to Health Canada, the average fetal dose of radiation from a chest X-ray is less than 0.01 milligrays (mGy)1. To put that number into context, one could consider traveling by airplane, where cosmic radiation levels are higher than those at ground level. For example, a round trip between Toronto and Vancouver can UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 3 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky expose the fetus to 0.05 mGy of radiation, an amount exceeding that of a chest X-ray2. Travel by air during pregnancy is not restricted until the last weeks of gestation and is deemed safe by physicians3. Perhaps advice to travel by air is unsound or there is a misperception of the safety of chest X-rays. As soon-to-be physicians, we are trained to be cautious when treating a pregnant woman because there are two lives and a potential family that need to be considered. We must counsel on issues from immunization status to prevent congenital varicella syndrome as well as eliminating soft cheeses from the diet for fear of developing listeria. Are we sometimes inappropriately cautious to the detriment of our patients? Are necessary diagnostic tests not being performed in pregnant individuals because of perceived risk or because of a true risk of radiation to the fetus? Our objective was to determine if a chest X-ray in pregnant women is considered harmful to the fetus. METHODS An Ovid MEDLINE search (from 1967 to present) was performed using the following MeSH headings: 1. Pregnancy; 2. X-ray; 3. Abnormality, radiation induced OR neoplasm, radiation induced. The search was limited to the English language and human studies. The search yielded 23 articles, eight of which were selected. Those not selected included articles about radiation exposure pre-conception, infants exposed to radiation, or total body radiation. These articles were not suitable for the scope of the question asked. UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 4 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky RESULTS Two of the earlier studies, from the 1980’s, demonstrated an increased risk of childhood cancers in children who were exposed to ionization radiation in utero 4,5. These studies, however, included radiation to the abdomen in their group of radiation procedures (before ultrasound technology was available for use in pregnancy, abdominal X-rays were used to determine intrauterine diagnoses). Upon closer examination of these studies, they differentiate between radiation modalities. For instance, in Shino et al’s (1980) study, the only sub-analyses of each radiation procedure that showed a significant increase in risk of malignancy was found in mothers exposed to intrauterine diagnostic X-rays. In a later study evaluating pre-natal X-ray exposure and occurrence of rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood, they found significantly higher odds ratios of exposure to a group of radiation modalities. Again, when they specifically looked at chest x-rays there was no significant increase in risk of the fetus later developing rhabdomyosarcoma6. These studies may have set a precedent of general fear of any radiation of pregnant women and poor fetal outcomes. To address the fear of radiation in pregnant women, the Motherisk group, which provides information and consultation to women and health-care professionals concerned about antenatal exposure to drugs, chemicals, radiation, and infection, concluded that a majority of diagnostic procedures expose the fetus to radiation levels well below the teratogenic range1,7. Rathapalan and others (2008) emphasized that when the fetus is not directly in the field of radiation, fetal exposure is a result of indirect scattered radiation from maternal tissue, and can be further reduced with a lead shield. When looking at the association of radiation exposure and specific outcomes, CohenUTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 5 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky Kerem and others (2006) found no significant increases in still births, prematurity, low birth weight or major malformations9. Although a majority of radiation procedures are below the teratogenic range, it would be helpful in decision making, to know at what dose a procedure is considered harmful. In assessing how much radiation is truly harmful, a review article looked at multiple imaging modalities and their associations with fetal outcomes such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and congenital abnormalities. They found no increased risk in either of these outcomes with radiation below 50 mGy8, a number that far exceeds the fetal dose of 0.01 mGy found from a chest X-ray on a pregnant mother. Further, Brent (1986) concluded that the maximum risk of 10 mGy exposure causing the aforementioned fetal outcomes is 0.003%, a rate which is thousands of times smaller than spontaneous rates of said outcomes. Almost 20 years later, a review evaluating the risk of the fetus developing IUGR or mental retardation as a child, found that these outcomes only occurred at doses of radiation that would cause radiation poisoning 9. In addition, they did not find evidence of any congenital malformations associated with radiation less than 50 mGy. The dose of radiation found in chest X-rays is convincingly within safe levels. UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 6 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky Table 1. Average fetal dose from X-ray procedures (Health Canada)10 Diagnostic type Average dose (mGy) Dental <0.01* Chest <0.01 Mammography <0.05* Pelvis 1.1 Abdomen 1.4 Lumbar spine 1.7 Natural background radiation (entire pregnancy) 0.5* Barium meal (Upper GI fluoroscopy) 1.1 Barium enema (fluoroscopy) 6.8 Head CT <0.005 Chest CT 0.06 Lumbar spine CT 2.4 Abdominal CT 8.0 Pelvis CT 25 *Estimates made by Health Canada CT: computerized tomography UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 7 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky DISCUSSION With a focus on the low dose of ionizing radiation and indirect exposure to the fetus, the evidence suggests fetal safety when exposed to radiation from chest X-rays. Compared to spontaneous rates of major malformations (2-3%), IUGR (4%), genetic disease (8-10%) and spontaneous abortions (15%), a 0.003% risk of poor fetal outcome when exposed to 10mGy of ionizing radiation is considerably well below those spontaneous rates8. In a patient presenting with hemoptysis, such as in the case, the outcome of missing an important diagnosis far exceeds the small risk associated with 0.01 mGy of radiation from a chest X-Ray. Despite the decades of evidence, patients and physicians are still unaware of the safety of chest X-rays during pregnancy. These misperceptions of chest X-ray safety can wrongly bias a physician’s care of the pregnant patient and the patient’s own perceptions of the pregnancy. The Motherisk group observed a higher rate of pregnancy termination in women who had been exposed to different forms of radiation11. Upon further investigation, they noted that these women were terminating their pregnancies for fear of damage to the fetus from the radiation. Specifically, the women who had radiation procedures perceived a 25% risk of malformation compared to those who had not (16%). After a consultation session, where experts explained the true risk of imaging procedures during pregnancy, the perceived risk in the group that did receive procedures dropped to 16.5%11. This study highlights the importance of education to change the incorrect paradigms, of radiation and pregnancy, paradigms that were developed during a time when radiation technology was used in a more harmful way. UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 8 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky CONCLUSION Chest X-rays expose the fetus to radiation levels far below the teratogenic range. This procedure is considered safe during pregnancy and if necessary, it should be performed. Women who have had X-rays should be reassured that they are safe (i.e., there is no need to terminate pregnancy for this reason). Patient and physician misperceptions about X-rays during pregnancy can bias which investigations are deemed appropriate. A further study of physician perception of radiation during pregnancy could further our understanding of how, despite good evidence and Health Canada guidelines, there is still a misperception regarding its safety. UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 9 of 10 Amaris K. Balitsky REFERENCES 1. Cohen-Kerem R. Nulman I. Abramow-Newerly M. Medina D. Maze R. Brent RL. Koren G. Diagnostic radiation in pregnancy: perception versus true risks. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology Canada: JOGC. 2006; 28(1):43-8. 2. Barish RJ. In-flight radiation exposure during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 103(6):1326-30. 3. SOGC: Women’s health information: pregnancy [Internet]. Society of Obsterics and Gynaecology; modified 2010 August 18 [cited 2012 March 18]. Available from: http://www.sogc.org/health/pregnancy-beginnings_e.asp 4. Kneale GW. Stewart AM. Prenatal x rays and cancers: further tests of data from the Oxford Survey of Childhood Cancers. Health Physics. 1986; 51(3):369-76. 5. Shiono PH. Chung CS. Myrianthopoulos NC. Preconception radiation, intrauterine diagnostic radiation, and childhood neoplasia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1980; 65(4):681-6. 6. Grufferman S. Ruymann F. Ognjanovic S. Erhardt EB. Maurer HM. Prenatal X-ray exposure and rhabdomyosarcoma in children: a report from the children's oncology group. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009; 18(4):1271-6. 7. Ratnapalan S. Bentur Y. Koren G. "Doctor, will that x-ray harm my unborn child?". CMAJ. 2009 Apr 28;180(9):952 CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008; 179(12):1293-6. 8. Brent RL. The effects of embryonic and fetal exposure to x-ray, microwaves, and ultrasound. Clinics in Perinatology. 1986; 13(3):615-48. 9. Bianca S. Health risks of low-dose ionizing radiation in humans. Experimental Biology & Medicine. 2005; 230(2):99-100. 10. Diagnostics and Pregnancy [Internet]. Health Canada; modified 2006 Dec 15 [cited 2012 March 18]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hl-vs/iyhvsv/med/xray-radiographie-eng.php 11. Bentur Y. Horlatsch N. Koren G. Exposure to ionizing radiation during pregnancy: perception of teratogenic risk and outcome. Teratology. 1991; 43(2):109-12. UTMJ REVIEW ARTICLE SUBMISSION Page 10 of 10