Theories of Employee Motivation

advertisement

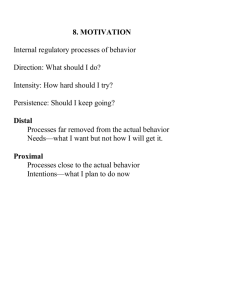

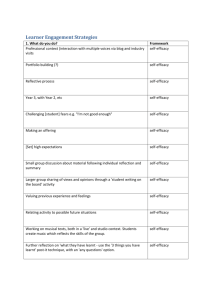

Theories of Employee Motivation 1.0 Need Theory 1.1 Introduction Need theories see motivation arising from individual needs or desires for things. These needs and desires can change over time and are different across individuals. There are three popular perspectives on Need theory: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Alderfer’s ERG Theory Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory This lesson briefly highlights the distinctions of each perspective. 1.2 Hierarchy of Needs Abraham Maslow proposes that motivation can be represented as a hierarchy of needs. As lower-level needs are satisfied, workers are likely to be motivated by higher-level needs. Maslow argues that there are five categories of needs: physiological, safety, love, esteem, and actualization. Physiological needs - basic biological needs for things such as food, water, and sex Safety needs - need for safety and a safe physical environment (e.g., shelter, a safe workplace) Love needs - need for friendship and partnership Esteem needs - need for self-respect and for the respect of others Self-actualization needs - need for self-improvement, fulfillment of personal life goals and of one’_ potential Tension-reduction - According to Maslow’s tension-reduction hypothesis, an unmet need creates a tension to meet that need. For example, if you need food, you feel tension until the need is met. Maslow believed that needs were arranged hierarchically such that lower, more basic needs must be met before higher needs become the point of focus. 1.3 ERG Theory Alderfer’s ERG Theory suggests that there are three classes of needs, not five as Maslow suggests: existence, relatedness, and growth. Another distinction is that Alderfer proposes that when low-level (existence) needs are not met, they grow. For example, when you are hungry and do not eat, your hunger grows. On the other hand, higher-level (relatedness and growth) needs grow when they are met. For example, as you become more productive, your need to be productive may grow. Existence needs - need for concrete, tangible things like food, water, and material possessions Relatedness needs - social needs and the need to have relationships with other people (e.g., family, co-workers, and supervisors) Growth needs - need for self-improvement or personal growth, expression of creativity and productivity Frustration-regression - According to Alderfer’s frustration-regression hypothesis, when we have trouble meeting a particular need, we regress to meet needs at a lower level. When we are having trouble meeting growth needs, we are more motivated by relatedness needs. When we are having trouble meeting relatedness needs, we are motivated by existence needs. 1.4 Two-Factor Theory In his Two-Factor Theory of motivation, Frederick Herzberg argues that there are two types of factors involved in motivation: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic (or hygiene) factors include tangible outcomes and things that focus on workers’ physical well-being such as pay and benefits, organizational policies, quality of supervision, job security, job safety, administrative practices, and physical work conditions. Intrinsic factors include intangible outcomes such as recognition, responsibility, and respect. 1.5 Motivator factors Motivator factors - Workers are satisfied and motivated when they are happy with the intrinsic factors (e.g., levels of responsibility and respect at work), which is why intrinsic factors are also called motivator factors. When workers are not happy with intrinsic factors, argues Herzberg, they are not satisfied. However, when they feel respected and enjoy the responsibility, they are more likely to be truly satisfied with their jobs. This suggests that we should focus our attention on intrinsic factors if we want to motivate employees. Non-motivator factors - Herzberg argues that workers will be dissatisfied with their job when they are not happy with the job’_ extrinsic factors (e.g., pay). An appropriate level of extrinsic factors is necessary to avoid job dissatisfaction, but even when employees are happy with their salary, bonus, vacation, and health benefits, they will not necessarily feel satisfied or motivated. With extrinsic factors, Herzberg argues, the best you can hope for is to keep your employees from feeling dissatisfied. The following chart summarizes these points: Extrinsic Factors Intrinsic Factors Dissatisfied Not Dissatisfied Not Satisfied Satisfied 1.6 Summary Need theory was once very popular, but none of the perspectives discussed have shown much relation to on-the-job performance. One possible reason is that these theories are too general. The needs they describe could be satisfied in many different ways, and so are not necessarily associated with job behavior. On the other hand, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Alderfer’s ERG Theory, and Herzberg’s TwoFactor Theory have contributed to our understanding of motivation by showing how people can vary in the rewards they want from work. 2.0 Behavioral Theories 2.1 Introduction Two important motivation theories that stem from behavioral psychology are reinforcement and expectancy theories. Both emphasize that behavior is shaped by rewards and punishment. Behavioral theories of motivation advocate the use of behavior reinforcement schedules to shape on-the-job performance. 2.2 Reinforcement theory The central premise of reinforcement theory is that the consequences (or outcomes) of behavior influence the likelihood that people will behave the same way again. For example, let’s say you make a suggestion in a committee meeting. If people respond positively, you are more likely to make other suggestions in other meetings. If people respond negatively, you are less likely to make other suggestions in other meetings. 2.3 Reward and Punishment Behavior can be motivated in four ways: through positive or negative reinforcement and by inflicting or removing a punishment. Positive reinforcement is a form of reward that involves giving the person something that is liked or wanted as a consequence of some behavior. For example, organizations give workers bonuses and bosses give praise for jobs well done. Negative reinforcement is a form of reward that involves taking away something that is disliked as a consequence of some behavior. For example, the removal of the sound of an alarm is a reward for waking up enough to turn off the alarm. Something Liked Something Disliked Give + Reinforcement (bonus) Punishment (spank, KP duty) Take away Punishment (ground, demote) - Reinforcement (turn off alarm) Punishment - People can be punished for doing something inappropriate by the removal of something they like or by the addition of something they dislike. For example, in response to bad behavior, some parents may take away things that their children like (e.g., the ability to use the car, talk on the phone, or watch TV). Other parents may instead give their children something they do not like to receive (e.g., a spanking, a lecture, or additional chores). 2.4 Reinforcement Schedules Behaviorists have recognized that rewards can be given in different ways: through continuous, partial-ratio, and partial-interval schedules. Continuous reinforcement occurs when people are reinforced or rewarded after every correct behavior. For example, fur trappers are rewarded after each successful trap; people who work on commission are rewarded after each successful sale. Partial reinforcement occurs when people are reinforced or rewarded after certain correct behaviors. Partial reinforcement can take two general forms: ratio and interval schedules. Ratio schedules reward people after some number of correct behaviors. People who are paid on piece-rate pay schedules get paid for every number of items they make, sell, and so on. This type of reinforcement schedule rewards the quality or amount of work without considering the time spent to meet the pay quota. This can cause problems. Workers can spend a lot of time performing well, without a reward. Interval schedules reward correct behaviors after some time interval. Organizations often adopt a regular pay schedule (e.g., every Friday, every other Friday), and set up rewards based on seniority (e.g., three-year bonus, promotion opportunities). Although this system rewards people for the time they spend working, it does not capture the quality of the work performance. In the worst scenarios, lazy workers are rewarded for their ability to avoid termination rather than perform successfully. Since both ratio and interval schedules have their strengths and weaknesses, most standard compensation systems provide both time-based and performancebased rewards. 2.5 Expectancy Theory Whereas Reinforcement Theory explains how different types of reinforcement shape behavior, Expectancy Theory explains when and why reinforcement impacts behavior. The Motivation Formula - According to Expectancy Theory, motivation is a function of an individual’_ confidence that he/she can perform a behavior successfully (expectancy) and that performing successfully will lead to a desirable outcome (valence and instrumentality). Motivation can be expressed as a mathematical equation: Force = Expectancy x (Valences x Instrumentalities) Force is the amount of motivation a person has to engage in a particular behavior (e.g., motivation to be highly productive at work). Expectancy is the confidence an individual feels that he/she can perform the behavior successfully. This is normally stated as a probability (e.g., 80% confident that I can be highly productive). Instrumentality is the confidence an individual feels that performing the behavior will result in a particular outcome. Again this is expressed as a probability (e.g., 80% sure that high productivity will lead to a raise or promotion). Valance is the value a person assigns to that outcome (e.g., a raise would be highly desirable but a promotion would be even more desirable). This formula suggests that motivation (force) cannot exist unless the individual possesses at least some expectancy, instrumentality, and valance. 2.6 Summary An overwhelming amount of research has shown two reliable trends. (1) When people are rewarded, they are more likely to repeat the behavior that resulted in the reward. (2) When people are punished they are less likely to behave in the same way again. This suggests that organizations can use reinforcements or rewards to promote desired behaviors... and they do. For example, the Emery Freight Company used reinforcements to speed up employee's responses to customer requests and to improve the quality of item packaging. These improvements saved the company 3 million dollars over 3 years. 3.0 Self-efficacy Theory 3.1 Introduction Albert Bandura’s (1982) Self-efficacy Theory asserts that motivation and performance are in part dependent on the degree to which the individual believes he/she can accomplish the task. 3.2 Defining self-efficacy Self-efficacy refers to a person’_ belief in his/her ability to perform a given task. The term is similar in meaning to self-confidence and expectancy, though some argue that there are differences among these terms. Self-efficacy is sometimes confused with self-esteem also. Self-efficacy and self-esteem - Self-efficacy is like self-esteem in the sense that it is related to a person’s feelings of self-worth. Self-efficacy, however, refers to one’s ability to perform a certain task, whereas self-esteem reflects a more general belief about one’s self-worth. You can have strong feelings of self-worth while still recognizing that you are not good at a particular task (e.g., crossword puzzles). On the other hand, having low self-esteem may cause you to undervalue your ability to perform a particular task. 3.3 Self-efficacy and motivation Research has found that self-efficacy does predict performance. Self-efficacy and the self-fulfilling prophecy - Those who have high self-efficacy are more likely to try hard and exhibit high levels of commitment (persistence) on a given task. They are more likely to succeed as a result. Those who have low levels of self-efficacy feel that they are not good at the task and may not try very hard at all. They are less likely to succeed. Self-efficacy and success - Self-efficacy may develop from prior good performance. Similarly, previous failures can lead to low self-efficacy. Self-efficacy and goal-difficulty - Self-efficacy interacts with goal setting insofar as people with higher self-efficacy tend to set more challenging goals. Self-efficacy and goal-commitment –_Commitment (or persistence) refers to one‘_ ability to overcome obstacles in the pursuit of a goal. With more demanding goals and higher levels of commitment, people with high self-efficacy put forth greater effort in performing the task (accomplishing the goal). 3.4 Empowerment Theory Empowerment theory is an extension or application of self-efficacy theory. It has been used widely in organizational settings. According to empowerment theory, motivation will increase when one’_ feelings of competence and self-determination increase. When people have high self-efficacy, they feel more competent and more capable of self-determination. Therefore, improving self-efficacy is a critical component of empowerment efforts. 3.5 Empowerment Strategies Common examples of empowerment strategies are participatory management practices and flextime. Participatory decision-making - Sometimes organizations empower employees by asking them to participate in making organizational decisions (e.g., What can we do to cut down on the number of accidents?). Flextime - Flextime is a program that allows workers to design their own work schedule, within certain constraints. People can choose to work a 9 to 5 day, or an 8 to 4 day, or sometimes a 10 to 6 day. Flextime allows the worker to structure the workday, but usually requires workers to be at work during core hours (e.g., 10 to 11 and 1 to 4) so that committees can meet and group work can be completed. Research has shown that participatory decision-making can increase commitment to the decision that is made and improve motivation. The research on flextime has shown that job performance and job satisfaction do benefit from flextime programs, but only sometimes. The most reliable benefit seems to be reduced absenteeism. Flextime allows time for doctor’s and dentist’s visits, late mornings, early days, and midday engagements, and reduces work-family conflicts. 3.6 Summary Self-efficacy can be useful in improving motivation to perform. Gradually increasing task (or goal) difficulty enables the learner to improve while experiencing success, which in turn should improve self-efficacy. Providing training and performance supports (job aids, quick reference guides, etc.) may also improve self-efficacy. Empowering people, by increasing their levels of decision-making and control, can also motivate people to perform, assuming their self-efficacy is high enough to support feelings of competence and self-determination. Limitation - One possible limitation of self-efficacy theory is individual ability. People sometimes don’_ believe in their ability to perform a task because they really may not be good at the task and know this from previous experience. Training, performance support, and graduated task difficulty strategies may not always be able to overcome a lack of ability. 4.0 Equity Theory 4.1 Introduction J. Stacey Adams’ (1965) Equity Theory (a.k.a., Social Exchange Theory) suggests that effort depends on one’s perceptions of fairness. According to this theory, people compare their input/output ratio to those of similar others. When the ratio reflects an inequity, tension is created and so people work to reduce that tension. 4.2 Input/Output Ratio The critical element in this theory is the perceived ratio of one’s inputs (what I give) to outputs (what I get in return) with respect to other’s ratios (what they receive and what they give). Inputs include what the person contributes - their qualifications, their past experiences, seniority, their effort, the time they spend on the job, and so on. Outputs include what the person is given in return - for example, pay, benefits, appreciation, respect. Our notion of "equity" is closely linked with our perceptions of justice and fairness. Adams asserts that as we act to satisfy our needs, we each assess the fairness of the outcome. Each of us asks, “Am I getting what I deserve in this exchange?” 4.3 Inequity tension According to equity theory, when people feel that they give more and get less in return than their co-workers, they feel tension (resentment). Also, when people feel that they get more than their peers, they feel tension (guilt). To reduce this tension people are motivated to: Adjust their inputs (e.g., work harder or slack off) Sabotage an “overpaid” worker or the organization Find ways to make up for the inequity (e.g., theft) Avoid the inequity by quitting Research has shown that people are motivated to act when they feel cheated. Less research supports the idea that people are motivated to act when they are overpaid in some way. 4.4 Procedural justice Equity Theory was popular among industrial/organizational psychologists at one time, but interest in it began to decline in the mid 1980s. While research has found that employee perceptions of inequity correlates with intentions to quit and job search behavior, it is often difficult to tell what workers will perceive as inequitable and how they will respond to inequities. It may vary by individual even within a given context. Lacking the ability to use it to predict motivation and performance, Equity Theory has fallen out of favor. However, in the 1990s, fairness research began to focus on the idea of procedural justice, which deals with the perceived fairness of the distribution process. It may be more important to know if employees perceive the reward distribution process as fair than whether or not they perceive the reward itself as equitable. 4.5 Summary Equity Theory emphasizes the importance of employee perceptions about input/output ratios. When employees believe that they are over or underpaid, the resulting tension motivates them to eliminate the inequity. Limitation - While this is helpful to know, in that it focuses our attention on potential inequities, it is not does not necessarily help managers predict when individuals will feel cheated. Without this predictive capability, the theory has limited application. Procedural justice theories focus on reward processes, rather than the rewards themselves. Future equity research is likely to focus on both the equity of the reward distributions and the fairness of the distribution process. 5.0 Goal-Setting Theory 5.1 Introduction Building on Bandura’s self-efficacy research, Edwin Locke and Gary Latham (1990) proposed Goal-setting Theory. According to Goal-setting Theory, goals direct our mental and physical actions. Goals serve two functions: Goals serve as performance targets that we strive to reach. Goals serve as standards against which we measure our own performance. Locke and Latham argue that the outcome of your performance can affect your future effort. In this way, goals provide us with a means of regulating our effort. 5.2 Goal specificity Specific goals benefit motivation and performance more so than vague goals. Specific goals provide people with a sharper point of focus. For example, the goal “raise profitability 10% this year” is likely to be more effective than “Let’s be more profitable.” Research has shown that people who have vague goals are more likely to be satisfied with good performance even though they are capable of better performance. People also tend to give more effort when they are trying to reach harder goals. One might think that people would prefer jobs with easy goals, but they usually do not…jobs with easy goals are usually boring. Also, many organizations provide better rewards for meeting difficult goals than they do for meeting easier goals. Performance feedback impacts future effort. By measuring performance against goals, organizations are able to provide workers with feedback that enables them to regulate their efforts. Given the right circumstances, failure to meet a goal can motivate an individual to work harder. 5.3 Circumstance Research has shown that specific and difficult goals do motivate people toward their best performance. However, this happens only when the proper circumstances exist: Workers have the necessary qualifications to meet the goal Feedback is provided to assist the effort-regulation process Workers believe that they can meet the goal (i.e., have high self-efficacy) Workers are committed to the goal The goal is obtainable…wasted effort on an unrealistic goal is a demotivator 5.4 Management by objectives (MBO) Goal-setting theory has emerged as one of the top motivational theories for two reasons. First, the research suggests that it is very effective. Second, there has been an increase in the use of the Management by Objectives (MBO) strategy, which is a practical extension of goal-setting theory. With MBO, the manager and the individual employee meet and agree on performance goals, which are then used to evaluate the employee's performance later. MBO performance goals typically have the following characteristics: Are aligned with higher level goals (e.g., business unit, divisional, and organizational goals) Are mutually agreed-upon (so there is buy-in from the employee) Specify behavior (e.g., reduce data entry errors for a particular department) Specify measurable evaluation criteria (e.g., reduce errors by 20%) Specify when the goal will be achieved (e.g., by the end of the first quarter) Specify who is responsible (e.g., names of task force members) Often identify resources that will be needed (e.g., training, materials, job aids, etc.) Sometimes identify interim performance checks (e.g., weekly progress reports) 5.5 Summary Since the 1990s, Goal-setting Theory has become the predominant achievement motivation theory in industrial/organizational psychology and has demonstrated its effectiveness in organizational settings. According to Locke and Latham, people are motivated by the prospects of meeting specific, difficult goals. Limitation - In response to goal-setting theory, other researchers have argued that setting specific, difficult goals is not always beneficial. It places the focus on performance, which is not beneficial to novice workers who are still trying to learn job tasks and duties. Placing the focus on performance can disrupt the novice’s ability to develop useful strategies. Consequently, setting specific, difficult goals can benefit performance, but only after the worker has had some time to learn and explore aspects of the job.