MEN AND CHILDCARE – AN ISSUE FOR PUBLIC POLICY

advertisement

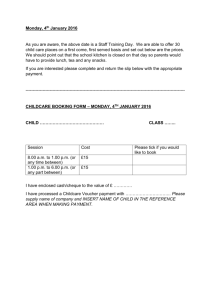

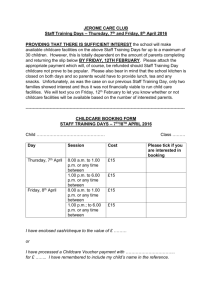

MEN AND CHILDCARE – AN ISSUE FOR PUBLIC POLICY?1 Paul Callister Paekakariki INTRODUCTION In recent decades throughout the OECD there have been a variety of public policy initiatives to help achieve equality for women in paid work. However, within most of these countries there has been a reluctance to develop complementary policies and strategies that would encourage more equal sharing of non-market work, including childcare, within the home.2 But is unpaid work within the home, and specifically childcare by fathers, an area to which New Zealand policy makers need to give more thought? Since the Second World War, as a result of changing economic circumstances, changing social values, and the effects of public policy, there has been a substantial increase in the participation in paid work by women, particularly mothers with young children. However, in more recent times there has been a significant increase in male unemployment which has removed many fathers, particularly Māori and Pacific Islands fathers, from the paid workforce (Figure 1). In addition, often through no choice of their own, another group of men has moved into part-time or part-year paid work, with Pacific Islands men and Māori again over-represented in this group (Davey and Callister 1994). Overall, in 1986 there were just over 6,900 partnered fathers with a child under five who were not in paid work (4.8% of partnered fathers), but this had risen to just over 22,900 (16%) in 1991. While unemployment amongst men has declined since 1991, it is still likely that there are a significant number of fathers who are not in paid work. These labour market changes mean that in a significant number to tow-parent families mothers now have less time available to be with their children, while fathers have more time at their disposal which, potentially, could be used in childcare.3 1 This research has been made possible through grants from the Foundations for Research, Science and Technology. 2 In this paper I am discussing two parent, heterosexual families. However, it is recognised that children are reared in a wide variety of family types. Perhaps, the largest group is single parents, including a small number of sole father families. But other child rearing family types include gay or lesbian couples, grandparents or other relatives. Within two parent, heterosexual families there are also increasing variations, with divorce and reconstitution of families, adoption and new fertility technology creating a diverse variety of biological and non-biological relationships. 3 The growth of one-parent families mainly headed by mothers also means that one group of men are potentially having even less to do with their children than in the past, but sometimes not through their own choice. But while the New Zealand Government has long had an interest in the workings of the paid labour market, historically there has been a reluctance to analyse or attempt to influence what goes on in the private world of families. One of the consequences of this is that few official studies on unpaid work have been conducted within a family setting. But whether it likes it or not the state is increasingly being drawn into taking a stand on many issues which were once considered "off limits". For example, welfare and justice agencies are increasingly drawn into the family unit, with a particular focus on men's behaviour, when dealing with issues such as domestic violence and child abuse. The courts in New Zealand are dealing with complex custody cases both within national boundaries and across them, and having to rule on issues such as whether a father has the right to have a say in abortion decisions. In the United States, the courts have also dealt with fathers' rights to parental leave and even the rights of single men to adopt children. In many countries the state now takes a responsibility for ensuring that fathers have an on-going financial commitment to their children even if they are no longer living with them. And now the official language emphasises gender-neutral terminology such as "parental leave" and "parents as first teachers", even if it is still overwhelmingly women who use such policies. Figure 1 Percentage of Fathers in Two Parent Families Not in Paid Work by Ethnicity of Both Parents – Youngest Child Under Five - 1991 Source: Census, Statistics New Zealand However, often the interest in New Zealand in fathers and their relationships with their children centres upon the major problems which a small number of men create. In contrast, policy makers within parts of Europe, and especially Sweden, have tried to develop public policies which actively encourage men to assume an equal share of childcare and other household work, based on the underlying view that such change is good for children, women and ultimately the men themselves. So what are the arguments for developing policies for greater involvement by men in childcare, and within the research literature what policies appear to be effective in encouraging such a shift while ensuring positive outcomes for children? SHOULD MEN SPEND MORE TIME LOOKING AFTER CHILDREN? There are of course a wide variety of views as to whether men "should" look after children. Some people feel that all men pose a potential danger to children and so contact should be minimised; some feel that men just do not have the natural ability to nurture, while some suggest that both women and men should minimise their unpaid work of caring for children and the work should be professionalised. Others argue, however, that even if much of the work is professionalised, men need to increase their relative share of the remaining unpaid care of children. The arguments for increased involvement by men in unpaid childcare revolve round three broad themes: benefits to women; benefits to children; and benefits to men. Benefits to Women It has been argued from a labour market perspective that women will always be constrained in public life if men are not taking an equal share of work within the private sphere (Folbre 1994, Rantalaiho 1993). For dual market-income families, where children may be cared for outside of the home while both parents are at paid work, mothers can suffer from a "dual burden". That is, they still retain the major responsibility for the unpaid work at home while having the main responsibility for organising, and often paying for, the childcare. This often represents a major constraint on their opportunities in paid work. New Zealand census data shows that the proportion of partnered mothers in full-time work, that is 30 or more hours per week, increases steadily from the time a child is born until it leaves school. However, in 1991, even by the time the youngest child reached the age of 15, only 52% of partnered women worked full time, 35% 40 or more hours per week, and just under 10% 50 hours or more. In comparison, despite the high levels of unemployment amongst fathers, 74% of partnered fathers with a child under 1 year worked 40 or more hours per week, rising to 80% with a child in the 5-15 age group. In addition, with a child under 1 year, 30% of partnered fathers worked 50 or more hours per week, rising to 35% in the 5-15 age group. These data emphasise the very long-term impact of having children on most women's paid work. This is of course just a snapshot at each age. However, longitudinal data by Lloyd, Fergusson, and Horwood (1990) indicate that a significant number of women may not sustain long-term full-time jobs. Figure 2 Percentage of Mothers and Fathers Working 40+ Hours Per week in Paid work – By Age of Youngest Child – 1991 Source: Census, Statistics New Zealand One solution to this would be for the Government to significantly increase the amount of state-funded childcare. This would include before- and after-school care, holiday care, as well as evening, night and weekend care. Some of this may well be justified in terms of educational outcomes for children. But Bittman (1991), in an Australian context, and Haas (1990), commenting on Sweden, argue that equalising parents' employment opportunities might be just as likely to come about through a lowering of men's involvement in the labour market as through the raising of women's involvement. Support for this idea comes from a range of sources including Dinnerstein (1977) and Chodorow (1978). who although differing in their analyses of the underlying reasons, have put forward theories that the oppression of women originates in the female monopoly on mothering. To counter this, they argue for the concept of dual parenting whereby men share equally in the rearing and caring of infants. But at the other end of the labour market spectrum to that of the dual market earners are the two-parent families where neither parent is in paid work. In fact, in just over 80% of two parent families in New Zealand with a child under five, where the father was not in paid work in 1991, the mother was also not in paid work. While attitudes and behaviours may be different in New Zealand, in the British context it has been found that as men drop out of paid work their partners often also move out of paid work (Cooke 1987). In relation to this, again in Britain, it has been suggested that benefit eligibility and abatement sometimes may discourage earning by spouses of unemployed people (Hills 1993). In many of these families, for a variety of reasons, both partners appear to try and retain traditional roles. For example, studies of unemployed men and their role in childcare in the UK suggest that when the man's partner is also at home he picks up little of the domestic work (Morris 1990, Lewis 1986). Morris suggests that this is partly because British working class men, who are the group of workers most likely to be unemployed, identify domestic labour as women's work. There is also some evidence of defensiveness from women who do not wish to surrender this role. But in New Zealand, in terms of moving families from dependency on welfare payments into paid work, given recent labour market trends for men and women, it may be better for the women to seek paid work and the men to take primary responsibility for caring for the children. This raises a range of policy questions as to how such a shift could be encouraged and as to whether major problems would be created for children if men were encouraged to be primary caregivers. Benefits To Children There are some studies that suggest that there may be positive gains for children from their fathers' greater involvement (Lamb 1986, Pruett 1987, Snarey 1993). More specifically Parker and Parker (1986) suggest that if a man is involved in the physical care of his child before they reach the age of three, there is far less likelihood that he will sexually abuse children, either his own or others, later in life. However, Lamb (1987) also reports that in many of the studies showing positive gains for the children from their fathers' involvement, the fathers were actively choosing to participate in childcare. This is important in a New Zealand context where many men with more time at home will have been forced into this position by unemployment. In discussing the possible good and bad effects of fathers being more involved in caring for their children it should, however, be noted that there has been very little research either in New Zealand or overseas on the effects of a high level of paternal involvement in childcare despite the apparent growth in the number of fathers who are primary caregivers (Callister 1994). Instead there has been an intense effort to analyse whether there are any harmful effects of reduced care by mothers as they increasingly moved into paid work. The Benefits To Fathers A number of psychologists and anthropologists suggest that men will gain emotionally from a greater involvement in their child's upbringing, with a potential additional benefit that they may also make better decisions in the public sphere with this new dimension to their being (Kitzinger 1992, Smith 1990, Snarey 1993). In addition there is some evidence that men who have had little contact with their children, in turn may have little emotional and practical support from them when they grow old, an important issue with an aging population. Having traditional roles can be costly for both parents if the relationship eventually dissolves. Finally, although it is not known whether similar attitudes exist in New Zealand, studies in the United States and Europe suggest that a significant number of fathers find that the paid work-time demands of their jobs are greater than they would prefer and that they would like to spend more time with their partners and children (Callister and Podmore 1995). WHAT FACTORS ENCOURAGE MEN TO BE HIGHLY INVOLVED IN CHILDCARE? If, in fact, policy makers want to find ways in which to shift the balance of unpaid work in two-parent households, the research literature gives some guide to the factors that appear to encourage men's greater involvement in childcare. Studies in several countries, including Sweden, Germany and the USA, suggest that younger fathers take a greater share in childcare (Nickel and Köcher 1987, Sandqvist 1987, Shelton 1992). In New Zealand too, there is some indication that, in general, younger people appear to have less traditional attitudes towards men's and women's roles (Gendall and Russell 1995). Fathers with fewer children appear more involved in their care than fathers with large families (Erickson and Gecas 1991, Nickel and Köcher 1987). In a review of Swedish and American studies Sandqvist (1987) suggests that more highly educated fathers participate more in childcare and housework. This finding, in relation to childcare, is also supported by New Zealand census data (Callister and Davey forthcoming). However, while higher levels of education may be associated with more egalitarian attitudes, they also frequently correlate with higher incomes. This indicates the complex nature of such associations. For instance, Erickson and Gecas (1991) show that as the father's income rises, his involvement in the household falls. Not surprisingly the influence of values in relation to fathers' involvement in childcare has been observed in the New Zealand context. Habgood (1992a:175) argues that in heterosexual couples, sharing of unpaid work is most equal and stable: "when strong "alternative" work and value commitments are held by the male partner". 4 The strong influence of non-traditional values is supported by Swedish and American studies (Sandqvist 1987, Shelton 1992). Ferree (1990) and Schwartz (1994) also note research that indicates that the sharing of household responsibilities is facilitated in situations where neither spouse places highest priority on achievements in paid work. The amount of time which women and men have available for unpaid work may also influence their roles within families. In Sweden, paid employment of mothers has been associated with more involvement of fathers in childcare (Sandqvist 1987), while in the United States mothers' involvement in paid work has also been associated with a greater sharing of general household tasks (Barnett and Baruch 1987). In New Zealand sharing of household tasks appears to be more common when mothers are in full-time paid work (Fleming and Easting 1994). However, an analysis of Australian time use data suggests that time spent by husbands on unpaid tasks does not increase in response to the time their wives devote to paid work (Bittman 1991). Overall data on links between mothers' employment status and fathers' participation in childcare and domestic work are inconsistent. There appear to be a range of confounding factors. For instance, the scheduling of work hours by parents, such as working different shifts, also effects 4 According to Habgood examples of these are "certain kinds of political, lifestyle, or personal development goals as opposed to those with careerist ambitions or who derive their primary identity from their paid work" (1992:176). availability for unpaid work and can influence men's roles (Erickson and Gecas 1991, Presser 1988). In some of these studies, the attitudes and work patterns of both mothers and fathers are, at times, influenced by government policies such as those determining childcare provision. But the aim and design of such policies are important. For example, Folbre (1994) argues that France offers a particularly generous and well-organised public childcare system which helps promote equality in paid work for women, but virtually all its employees are women and few, if any, aspects of French public policy encourage men to take a more active role in childcare. But more direct public policies have also been identified as influencing the behaviour of fathers. For example, parental leave policies, including government policies to protect the health of the mother and baby, can influence men's involvement in the early days of childcare (Galtry and Callister 1995). It has also been argued that taxation policies may influence the sharing of unpaid work. For instance, Juster and Stafford (1991) note that Norwegian and Swedish taxation policies, through taxing couples' incomes separately and generating high marginal tax rates, may reinforce policies aimed at supporting more equal involvement between women and men in both market and unpaid work. In most of the studies noted, mothers were still the primary caregivers. However, in recent years a number of studies have been undertaken of families where the father is either the primary caregiver or undertakes an equal share of childcare.5, 6 The reasons for fathers taking up the role of primary caregiver appear to consist of a complex combination of factors, including those specific to the culture in which the study was carried out. There are ideological reasons, for example, the belief that children when very young are best cared for in the home by one of their parents (Nussbaum 1985, Radin 1988). But decision making concerning which parent stays home appears, at times, to have been influenced by "popular feminism" and a belief in the importance of breaking down traditional roles (Grbich 1992). The family experiences of both the mother and father also come into the decision-making process (Grbich 1992, Pruett 1987). In addition the ability of the mother to earn a "family" wage is obviously important (Nussbaum 1985, Radin 1988). The state of the job market, particularly the loss of full-time jobs for men and the growth of traditionally female occupations, also appears to be a factor (Grbich 1992, Russell 1983) as does the relative resources of the family (Grbich 1992, Russell 1983). It appears that there are also a range of other factors, often difficult to measure, such as the attitudes of the wider family, especially the parents' own parents, the local neighbourhood as well as society in general, which come into the decision-making process (Callister 1994). And while many of these analyses focus on social and economic 5 The studies cited are from the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia. These studies are analysed in more detail in Callister (1994). Included in this is a discussion of the wide variety of criteria used in defining who is the primary caregiver in a family. 6 factors, Grbich (1987) notes in her study that underlying the various reasons given for men being the primary caregiver was the fact that these men wanted to take an active role in looking after the children. Pruett (1987) suggests that his sample of male primary caregivers was not a homogeneous group with easily identified predispositions to fathering. He sees that finding no clear predictor is a positive finding that implies that the role is open to any father. However, Schwartz (1994), in a study of marriages in which unpaid work was equally shared, suggests that such couples are generally not to be found amongst baby boom professionals. Most were middle class consisting mainly of small business owners, social workers, school teachers and health professionals, although not doctors. She argues that it appears that men on career "fast tracks" are less willing to put at risk their potential income and opportunities for promotion. In reviewing literature on men and masculinity Segal (1990) hypothesises that men are more likely to accept a primary commitment to home and childcare in situations where they have already developed relatively high levels of personal self-satisfaction and independence; when they are older; where their partners are able to earn a higher income; where there are more supportive social networks or where there are fewer children and household demands are less demanding. Yet, in New Zealand, the fathers most likely to have time available to look after children tend to be young, unemployed, with partners who are also unemployed, and in families with above average number of children (Statistics New Zealand 1995). FACTORS WHICH WORK AGAINST MEN LOOKING AFTER THEIR CHILDREN Although there may be factors that increase the likelihood of men spending more time with their children are there factors which work against this happening? While many men may not want to spend more time with their children, research indicates that those men in paid work who wish to take on the more traditionally female pattern of working less than full-time in paid work may be constrained in their choices (Callister 1994). For example New Zealand research into the gender dynamics of "emotional labour", that is, the nurturing work which is crucial to the smooth running of the household, family and social support networks and in which women have tended to specialise, suggests that if men are to be successful in paid work there are strong pressures on them not to develop the skills associated with the performance of this type of work (Habgood 1992b). But it has been argued that even in Sweden, despite the existence of paid parental and sick leave policies which encourage men to take an equal share of looking after children, employers, particularly those in the private sector, are often negative towards men staying home with children (Hwang 1987). Also in Sweden, Stafford and Sundström (1994) have found that the long term loss of earnings associated with taking parental leave was higher for men than for women. They suggest that this raises the issue of whether employers interpret the taking of leave by men to look after children as a "signal" that they lack commitment to their careers. Studies in New Zealand, Australia and the United States also indicate that male primary caregivers face considerable reaction from their social groups, including their own parents. Some of these responses are positive, some positive with reservations, while the majority, at least initially, are negative (Grbich 1992, Hutchins 1993, Pruett 1987). For instance, the male primary caregivers in Grbich's (1992) study reported that comments from parents, friends, workmates, neighbours, community playgroup members as well as various representatives of the wider society often indicated that the role of the caregiver is not generally considered appropriate for men. Not surprisingly, a positive self-concept was enhanced when family and friends were supportive and accepting of the men being the primary caregiver. And in an attempt to explain why male primary caregivers sometimes encounter negative reactions from women, Gerson (1987), in a United States context, argues that many women who are full-time mothers now find themselves having to publicly justify their choice, and see the men moving into their traditional role as a further threat to this choice. In situations of shared caregiving in Australia, Russell (1989) suggests that some mothers are reluctant to give up the power and status they may have within the home, and find it difficult to be supportive of their partner in the childcare role. These findings are supported by Wainrib (1992) who, in an in-depth study of four professional women whose partners were primary caregivers, noted ambivalence on the part of these women toward their source of power in the home being taken over by their partners. And extending this observation beyond the home, research in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand indicates that formal organisations such as play groups, which can give support to mothers have, at times, not been welcoming to male primary caregivers (Grbich 1987, Hutchins 1993, Podmore and Sawicka 1995). There is also evidence to suggest that informal networks of childcare and support, often extensions of existing childcare groups, tend to exclude men (Grbich 1987, Rio 1993). According to Grbich, male primary caregivers often encounter difficulties in convincing not only other mothers but also other fathers that they are adequate caregivers with a genuine desire to participate in childcare activities. Moreover, many studies of fathers do not address very real concerns about male involvement in child abuse that is likely to be a major factor behind the reluctance to involve men in both formal and informal childcare arrangements (Segal 1990). However, this is not the case in recent New Zealand media articles where men have discussed their awareness of the child abuse issue, as well as strategies to deal with it (Playcentre Journal 1994, The Listener 1993). Overseas studies also indicate that "helping" professions often have not been very supportive of fathers becoming the primary caregiver (Callister 1994). However, even if men are confident and supported in the role of primary caregiver they often face, on a practical level, some seemingly small but potentially difficult problems. For example, an Australian researcher argues that nappy changing rooms tend to be located in the "ladies' lounge" or the "ladies' toilet" that are often marked by a sign depicting a woman with a child (Rio 1993). The male primary caregiver in Grbich's study (1992) made similar observations. Examples of public spaces designed for mothers only have also been common in New Zealand although this is slowly changing. THE ROLE OF THE NEW ZEALAND GOVERNMENT IN INCREASING FATHERS' SHARE OF CHILDCARE Bringing about changes or supporting those already taking place in the allocation of unpaid work within households is clearly going to be a major and complex task, and one in which government policy can be just one of the many influencing factors. But there appear to be some significant reasons why governments should be interested in men and childcare. Perhaps the most major one is a need to reduce child abuse. But other reasons include the need to improve the income, and reduce dependency on welfare, of families where the father is unemployed and the mother has a better chance of obtaining paid work; strengthening families in their variety of forms, including sole father families; encouraging separated fathers to play a greater role in care of their children, including, where appropriate, removing barriers which may work against this; ensuring that the education system not only encourages girls to expand their options, but that boys also come to value nurturing skills; and creating equal opportunities for women and men in paid work. Already the New Zealand Government has made some changes in this direction, such as in 1987 creating a statutory right for fathers to take paternity leave, and for extended parental leave to be gender neutral. At times the Government also appears to have provided a model for being a "good employer", with examples of men taking parental leave more likely to come from the public sector than the private sector (Galtry and Callister 1995). But Government can take further initiatives in this area by promoting research and debate around this issue. In doing so it would follow the lead of many European countries (European Commission 1990, European Commission 1993). In researching and developing policies related to men and childcare the experience of Sweden, in particular, could be drawn on, but with the caution that in Sweden such policies were developed during a period of "full employment", and in times when government spending was expanding. However, specific New Zealand research is also needed. In particular, the high levels of unemployment amongst Māori and Pacific Islands fathers in 1991 suggests that there should be research amongst two-parent families where fathers face long, or repeated, periods of unemployment. The aim of such research should be firstly to assess the effect of this on children and the labour market choices of both the fathers and their partners and secondly, to determine whether changes in patterns of unpaid work in these families could lead to a higher level of well-being for these families. REFERENCES Barnett, R. and Baruch, G. (1987) "Determinants of fathers' participation in family work", Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49, 29-40. Bittman, M. (1991) Juggling Time – How Australian Families Use Time, Office of the Status of Women, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australia. Callister, P. (1994) "Fathers as Primary Caregivers in Two Parent Families", paper presented to the 1994 New Zealand Association for Research in Education, December 1-4, Christchurch. Callister, P. and Podmore, V.N. (1995) "Flexible forms of paid work and parental care of children", in P. Callister, V.N. Podmore, J. Galtry, and T Sawicka (eds.) Striking a balance: Families, work and early childhood education, NZCER, Wellington. Callister, P. and Davey, J. (forthcoming) "Unpaid work in New Zealand: What can the official statistics tell us?" New Zealand Sociology. Chodorow, N. (1978) The Reproduction of Mothering, University of California Press, Berkeley. Cooke, K. (1987) "The withdrawal from paid work of the wives of unemployed men: A review of the research", Journal of Social Policy, 16 (3), 370-382. Davey, J. and Callister, P. (1994) "Parents in paid work: The workforce patterns of parents of children under five years of age", New Zealand Sociology, 9 (2), 216241. Dinnerstein, D. (1977) The Mermaid and the Minotaur: Sexual Arrangements and Human Malaise, Harper and Row, New York. Erickson, R. J. and Gecas, V. (1991) "Social Class and fatherhood", in F. W. Bozett and S. M. H. Hanson (eds.) Fatherhood and Families in Cultural Context, Springer Publishing, New York, pp. 114-137. European Commission (1990) Men as carers for children: Report on an EC childcare network technical seminar, Glasgow, European Commission Network on Childcare and other Measures to Reconcile Employment and Family Responsibilities for Women and Men, Brussels. European Commission (1993) Men as carers: Towards a culture of responsibility, sharing and reciprocity between women and men in the care and upbringing of children Report of an international Seminar Ravenna, Italy, May 21-22, European Commission Network on Childcare and other Measures to Reconcile Employment and Family Responsibilities for Women and Men, Brussels. Ferree, M. M. (1990) "Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research", Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 886-884. Fleming, R. and Easting, S. K. (1994) Families, Money and Policy, Intra Family Income Project, Wellington. Folbre, N. (1994) Who pays for the kids?: Gender and the structures of constraint, Routledge, New York. Galtry, J. and Callister, P. (1995) "Birth and the early months: The issue of parental leave and paid work", in P. Callister, V.N. Podmore, J. Galtry, and T. Sawicka (eds.) Striking a balance: Families, work and early childhood education, NZCER, Wellington. Gendall, P. and Russell, D. (1995) The roles of men and women in society, International Social Survey Programme, Department of Marketing, Massey University, Palmerston North. Gerson, K. (1987) "What do women want from men?: Men's influence on women's work and family choices", in M. Kimmel (ed.) Changing Men: New directions in research on men and masculinity,: Sage Publications, California, pp. 115-130. Grbich, C. (1987) "Primary caregiver fathers – A role study: Some preliminary findings", Australian Journal of Sex, Marriage & Family, 8 (1), 17-26. Grbich, C. (1992) "Societal response to familial role change in Australia: Marginalisation or social change?" Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 23 (1) Spring, 79-94. Haas, L. (1990) "Gender equality and social policy: Implications of a study of parental leave in Sweden", Journal of Family Issues, 11 (4), 401-23. Habgood, R. (1992a) "On his terms: Gender and the politics of domestic life", in R. Du Plessis et al. (eds.), Feminist voices – Women's studies texts for Aotearoa/New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Auckland. Habgood, R. (1992b) "Women's oppression: Born in the family or brought home with the pay packet?" in N. Armstrong et al. (eds.), Conference proceedings, Women and Work Conference – Directions and Strategies for the 1990s, Department of Sociology, Massey University, Palmerston North. Hills, J. (1993) The Future of Welfare: A guide to the debate, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York. Hutchins, G. (1993) Just you wait till your mother gets home!: Reflections of a New Zealand Househusband, Harper Collins Publishers, Auckland. Hwang, C. P. (1987) "The changing role of Swedish fathers", in M. Lamb (ed.), The father's role – Cross cultural perspectives, Hillsdale, New Jersey, pp. 115-136. Juster, T. F. and Stafford, F. P. (1991) "The allocation of time: Empirical findings, behavioral models, and problems of measurement", Journal of Economic Literature, Vol XXIX, 471-522. Kitzinger, S. (1992) Ourselves as mothers: The universal experience of motherhood, Doubleday, London. Lamb, M. (1986) The father's role: Applied perspective, John Wiley & Sons, New York. Lamb, M. (1987) "Emergent American father – Moving from breadwinner", in M. Lamb (ed.), The father's role – Cross cultural perspectives, Hillsdale, New Jersey, pp. 3-23. Lewis, C. (1986) Becoming a father, Open University Press. Lloyd, M., Fergusson, D. M., and Horwood, L. J. (1989) "A longitudinal study of maternal participation in the full-time workforce: Part 1: Entry into the full-time workforce" New Zealand Population Review, 15 (2) 3-22. Morris, L. (1990) The workings of the household, Polity Press, Cambridge. Nickel, H. and Köcher, E. (1987) "Public opinions, politics and statistical data – West Germany and the German speaking countries", in M. Lamb (ed.), The father's role – Cross cultural perspectives, Hillsdale, New Jersey, pp. 89-110. Nussbaum, J. (1985) Fathers as primary caretakers of infants, unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California. Parker, H. and Parker, S. (1986) "Father-daughter sexual child abuse: An emerging perspective", American Journal of Ortho-psychiatry, 56 (4), 531-549. Playcentre Journal (1994), Vol 89, March 21-24, New Zealand. Podmore, V. N. and Sawicka, T. (1995) "Parents' voices: Case studies of families' employment and childcare arrangements", in P. Callister, V. N. Podmore, J. Galtry, and T. Sawicka (eds.) Striking a balance: Families, work and early childhood education, NZCER, Wellington. Presser, H. (1988) "Shift work and child care among dual career parents", Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 3-14. Pruett, K. D. (1987) The Nurturing Father, Warner Books, New York. Radin, N. (1988) "Primary caregiving fathers of long duration", in P. Bronstein and C. Cowan (eds.), Fatherhood Today: Men's changing role in the family, John Wiley & Sons, Canada, pp. 127-143. Rantalaiho, L. (1993) Reshaping the gender contract, OECD, Paris. Rio, V. (1993) Who cares?: A psychoanalytic study of men as primary caregivers, Fourth Australian Family Research Conference, Institute of Family Studies. Russell, G. (1983) The Changing Role of Fathers? University of Queensland Press, Queensland. Russell, G. (1989) "Work/family patterns and couple relationships in shared caregiving families", Social Behaviour, 4, 265-283. Sandqvist, K. (1987) Fathers and family work in two cultures – Antecedents and concomitants of father's participation in childcare and household work, Doctoral Dissertation, Almqvist and Wiksell International, Stockholm. Schwartz, P. (1994) Peer Marriage: How love between equals really works, The Free Press. Shelton, B. A. (1992) Women, men and time: Gender differences in paid work, housework and leisure, Greenwood Press, New York. Segal, L. (1990) Slow motion: Changing Masculinities, Changing Men, Virago Press, New York. Smith, G. (1990) Will The Real Mr New Zealand Please Stand Up? Penguin Books, Auckland. Snarey, J. (1993) How fathers care for the next generation: A four-decade study, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Stafford, F. P. and Sundström, M. (1994) "Time out for Childcare and Career Wages for Men and Women", paper presented at the Sixth Annual Conference of the European Association of Labor Economists, Warsaw, September 23-25. Statistics New Zealand (1994) New Zealand Now: Families, Statistics New Zealand, Wellington. The Listener (1993) Looking for Mr Mum, September 18-24, New Zealand. Wainrib, B. R. (1992) "Successful women and househusbands: The old messages die hard", Psychotherapy in Private Practice, 11 (4) 11-19.