The Nature of Epistemology

advertisement

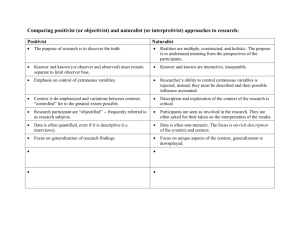

Extracted From: Huglin, L. M. (2003). The relationship between personal epistemology and learning style in adult learners. Dissertation Abstracts International, 64(03), 759. The Nature of Epistemology In their extensive review of epistemological research, Hofer & Pintrich (1997) define personal epistemology as follows: Epistemology is an area of philosophy concerned with the nature and justification of human knowledge. A growing area of interest for psychologists and educators is that of personal epistemological development and epistemological beliefs: how individuals come to know, the theories and beliefs they hold about knowing, and the manner in which such epistemological premises are a part of and an influence on the cognitive processes of thinking and reasoning (p. 88). Although there are many different epistemological terms, in general, epistemological beliefs are seen as ranging on a continuum from objectivism to subjectivism. Objectivism Objectivism (also referred to as evaluatism, empiricism, logical positivism, and dualism) espouses the belief that knowledge of the world is relatively fixed, exists outside the knower, and that learners can come to know the world as it really is. As Pratt (1998) puts it, “knowledge exists independent of the learners’ interest in it, or awareness of it…basic theories, principles, and rules which govern our lives and world exist quite separately from our experience of them; knowledge about the world exists ‘out there’ waiting to be discovered” (p. 22). Those who subscribe to the objectivist viewpoint believe that “the mind is…an empty bucket, a blank page, a tabula rasa waiting to be filled with sense impressions or the results of reasoning” (Ernest, 1995, p. 467). From the objectivist perspective, knowledge is obtained through experience and observation. One 1 can be said to know something when one can accurately describe or produce a mirror image of it. The more that one knows about a topic, the closer the representation of knowledge in that person’s mind is to the reality of the world. This is sometimes referred to as the “reality constructs the person” paradigm (Evans, 2000, p. 739). A key point in the objectivist perspective is that objective knowledge can, and should, be separated from one’s feelings about it; that is, that knowledge is value-free: From an objectivist point of view, truth is a matter of the ‘goodness of fit,’ or correspondence, between observation and description. Therefore, whether one is a scientist, journalist, teacher, or a citizen testifying at a trial, observations are expected to be neutral and represent no particular interests or purposes; descriptions, likewise, are to be an objective or detached report of what happened (Pratt, 1998, p. 23). Ryan & Aikenhead (1992) elaborate on this point by stating that “one vestige of (objectivism) is the belief that scientific knowledge connects directly with reality, unencumbered by the vulgarity of human imagination, dogma, or judgments” (p. 561). The role of authority in learning is a key feature of objectivism: “Authority is highly correlated to how much expert knowledge one possesses. The more one has knowledge or expertise validated through experience, observation, and experimentation, the more authority one holds over those who wish to have that knowledge” (Pratt, 1998, p. 22). In the context of teaching and learning, the objectivist model “views the teacher as the source of knowledge and students as passive receptacles of this knowledge. The objectivist learning model emphasizes learning by receiving information, especially from the teacher and from textbooks, to help students encounter facts and learn well-defined 2 concepts” (Howard, McGee, Schwartz, & Purcell, 2000, p. 2). Several learning theories and techniques are associated with this model, including behaviorism, direct instruction, cognitive information processing, Gagne’s instructional theory, and the Dick & Carey and ADDIE models of instructional design (Driscoll, 2000; Wood, 1995). The objectivist model also provides the theoretical basis for quantitative research. Those with objectivist leanings will be far more inclined to conduct quantitative, rather than qualitative, research. As stated by Gall, Borg, and Gall (1996): Positivist research is grounded in the assumption that features of the social environment constitute an independent reality and are relatively constant across time and settings. Positivist researchers develop knowledge by collecting numerical data on observable behaviors of samples and then subjecting these data to numerical analysis….Quantitative research is virtually synonymous with positivist research. (p. 28) Gall, et al., further state that quantitative researchers “assume an objective social reality,” “assume that social reality is relatively constant across time and settings,” “take an objective detached stance toward research participants and their setting,” and “prepare impersonal, objective reports of research findings” (Gall et al., 1996, p. 30). There seems to be some link between the tendency to subscribe to objectivist beliefs and the subject matter that is to be taught. Roth & Roychoudhury (1994), for example, maintain that at present, most science teaching is based on an objectivist view of knowing and learning. Here objectivism subsumes all those theories of knowledge that hold that the truth value of propositions that can be tested empirically in the natural 3 world. Science provides us with a methodology, the scientific method, that allows us to transcend subjective limitation of individuals to test propositions and, in this way, to ascertain absolute truths. (p. 6) Subjectivism The opposite end of the epistemological continuum is known as subjectivism (also referred to as interpretivism, absolutism, relativism, postpositivism, and social constructionism). Whereas objectivism is based on the logic of discovery, subjectivism is based on the logic of interpretation. Subjectivists discard the notion that reality is “out there” and instead endorse the idea that reality is what each person interprets it to be. As Pratt points out: Subjectivists are committed to quite different beliefs about knowledge and truth (than are objectivists)….knowledge (and truth) is dependent upon what individuals bring to the moment of perception. Knowledge and truth are created, not discovered; the world is only known through people’s interpretations of it…truth is arrived at not by seeking correspondence, but by seeking consensus; not by looking for a perfect match, but by finding a reasonable fit; not by assuming detachment but by assuming commitment. Truth, therefore, is relative rather than absolute; it depends upon time and place, purpose and interests (Pratt, 1998, p. 23). Contrary to the principles of objectivism, the learner’s feelings and emotions are an integral part of the subjectivist view. Learners are seen to be active makers of meaning, and do so in the context of the learning situation. A person’s background, prior experiences, and value system are crucial to their interpretation and construction of 4 knowledge. Individual meaning is tested against that of others through the process of social negotiation. Indeed, subjectivists believe that knowledge cannot be value-free since all incoming information is filtered through “the lens of our beliefs. We cannot detach our experience from the purposes and values that bring us to that experience. Believing determines what is seen. The separation of mind and world, observer and observed, subject and object, or learner and content must be rejected” (Pratt, 1998, p. 24). This general outlook has been called the “person constructs reality” paradigm, as opposed to the “reality constructs the person” paradigm that is aligned with objectivism (Evans, 2000, p.739) The roles of teacher and learner take on new meaning under the subjectivist viewpoint. “Teaching should be concerned with students’ construction of knowledge, with conscious thinking, and reflective practice that cannot be accomplished by methods that reflect ‘flat declarations of fixed factuality’…opportunities for learning occur during the social interaction in which participants are expected to take the perspective of another” (Wood, 1995, p. 332). Learning theories and methodologies that are associated with subjectivism include group problem-solving tasks, Piaget’s developmental theory, constructivism, critical thinking techniques, and model development—in general, approaches that create an atmosphere of active learning (Driscoll, 2000; Howard et al., 2000). Those who lean toward the subjectivist end of the epistemological spectrum are also far more likely to conduct qualitative research than are their objectivist counterparts. As Gall et al. explain, 5 Postpositivist research is grounded in the assumption that features of the social environment are constructed as interpretations by individuals and that these interpretations tend to be transitory and situational. Postpositivist researchers develop knowledge by collecting primarily verbal data through the intensive study of cases and then subjecting these data to analytic induction….While the terms positivist research and postpositivist research appear in the literature, it is more common to see the terms quantitative research and qualitative research, respectively, used to refer to the distinctions we made above. (Gall et al., 1996, p. 28) In addition, Gall et al. further state that qualitative researchers “assume that social reality is constructed by the participants in it” and “assign human intentions a major role in explaining causal relationships among social phenomena” as well as “study(ing) the meanings that individuals create and other internal phenomena” (Gall et al., 1996, p. 30). 6 References Driscoll, M. P. (2000). Psychology of learning for instruction (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Ernest, P. (1995). The one and the many. In L. P. Steffe & J. E. Gale (Eds.), Constructivism in education (pp. 459-486). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Evans, W. J. (2000). Construct validity of the Attitudes About Reality Scale. Psychological Reports, 86(3, Pt1), 738-744. Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., & Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational research: An introduction (6th ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman Publishers USA. Hofer, B. K., & Pintrich, P. R. (1997). The development of epistemological theories: Beliefs about knowledge and knowing and their relation to learning. Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 88-140. Howard, B. C., McGee, S., Schwartz, N. H., & Purcell, S. (2000). The experience of constructivism: Transforming teacher epistemology. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(4), 455-465. Pratt, D. D. (1998). Five perspectives on teaching in adult and higher education. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company. Roth, W. M., & Roychoudhury, A. (1994). Physics students' epistemologies and views about knowing and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 31(1), 530. Ryan, A. G., & Aikenhead, G. S. (1992). Students' preconceptions about the epistemology of science. Science Education, 76(6), 559-580. 7 Wood, T. (1995). From alternative epistemologies to practice in education: Rethinking what it means to teach and learn. In L. P. Steffe & J. E. Gale (Eds.), Constructivism in education. (pp. 331-339). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 8