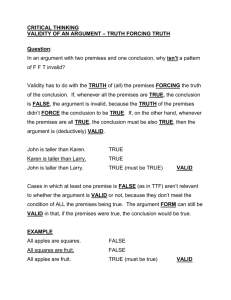

Critical Thinking - Buffalo State College Faculty and Staff Web Server

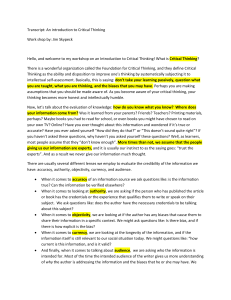

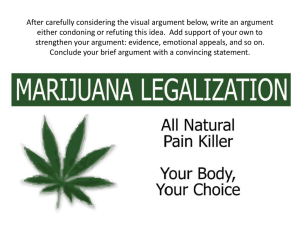

advertisement