Explanation

advertisement

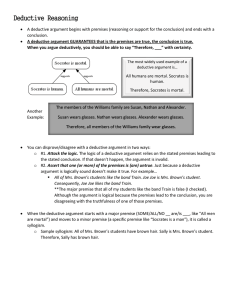

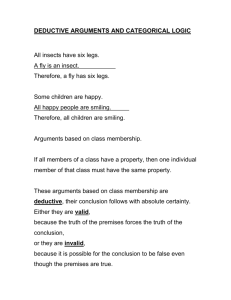

1 Philosophy 352: Philosophy of Science Dr. Jackie Kegley Explanation: Scientific and Otherwise Well-known philosopher of science, Ernest Nagel has written: “…the distinctive aim of the scientific enterprise is to provide systematic and responsibly supported explanations.” The Structure of Science ( 1961: Harcourt, Brace & World), p. 15. We will outline the characteristics of four different kinds of explanation. Deductive Nomological Explanation –explanation by subsuming under a general law. Answers question why: “Why did the wire holding the mobile break?” Such an explanation would go as follows: 1. For every wire of a given structure S (.e.g., a certain material, thickness, etc.), there is a characteristic weight W such that the wire will break if a weight exceeding W is suspended from it. 2. For every thread of the kind S, the characteristic weight W = K. 3. 3. T is a piece of wire of the kind S. 4. B, which is a weight greater than K, is suspended from T. 5. Therefore T breaks. Premises 1 and 2 are law like statements. Premises 3 and 4 are relevant factual statements. Statement 5 is the conclusion as well as a prediction in an identical case. The argument is deductive because the premises (called the explanans) offer logically conclusive grounds for expecting the event to be explained. Inductive-Statistical Explanation- In this case the individual case to be explained is subsumed under a statistical law and the premises do not deductively imply the conclusion, but give only inductive support. 1. Ninety percent of the persons in age group G have heart attacks. 2. Jones is in age group G. 3. Therefore, the probability of Jones having a heart attack is 90%. Notice: the conclusion is not “Jones will have a heart attack.” This conclusion does not logically follow because Jones could be among the 10 percent in the group who do not have heart attacks. The conclusion is only probable. 2 It is not the mere presence of statistical generalizations that renders an explanatory argument inductive and the mere absence of statistical generalizations from an argument does not render it deductive. Thus here is a deductive argument containing a statistical generalization. Six percent of all American cigarette smokers get lung cancer. (Stat.Gen) There are 100,000,000 American cigarette smokers. (fact) Necessarily, 6,000,000 American cigarette smokers will get lung cancer. Here is an inductive argument that contains no statistical generalizations. For every x. if x has a certain disease d, then x has a high pulse rate. For every x, if x has a certain disease d, then x has high blood pressure. For every x, if x has a certain disease d, then x has severe pains in his respiratory tract. For every x, if x has a certain disease d, then x has a fever. Mr. Jones has a high pulse rate, high blood pressure, severe pains in his respiratory tract, and a fever. Therefore, Jones probably has a certain disease d. (Any doctor knows this is only probable. Further it is the fallacy of affirming the consequence. Since the conclusion could still be false, when the premises are true, it is inductive.) Teoleogical explanation- answers if they question “why?” by reference to some end, goal, purpose or motive. 1. When supplied with water, carbon dioxide, and sunlight, plants produce starch. 2. If plants have no chlorophyll, even though they have water, carbon dioxide, and sunlight, they do not produce starch. 3. Therefore, Plants contain chlorophyll. This explanation could also be stated as follows: “The function of chlorophyll in plants is to enable plants to perform photosynthesis. Another example is: “The whiteness of the fur of the polar bears is due to the fact that, in their natural habitat, this makes it difficult for them to be seen by their prey.”