Adam Hennen Residence - Egypt Architecture Online

advertisement

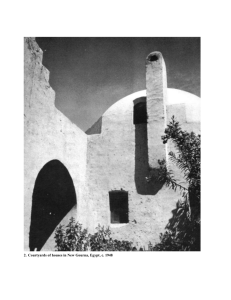

Adam Hennen Residence Location: Giza, Egypt Date : 1968 Century: 20th Decade: 1960s Building Type: residential Notes The Adam Henen Residense is a traditional house with a workshop for an Egyptian artist. The architect, through his design, sought to provide the artist and his family with a comfortable house and a functional workshop at a minimal cost. Adam Henen was a young sculptor, a pupil of Wissa Wassef, and shared his philosophy. He needed a place to live and work, and could not then afford to buy a conventional house. The site was large enough for the artist's studio to be in a separate building. The ground floor comprises a sitting room, dining room, study, and kitchen. The first floor contains two bedrooms and a bathroom. The choice of mud-brick as a material ensured not only that the construction cost would be kept to a minimum, but also that the thermal performance would be good. Domes and vaults are constructed from red brick and mortar cement. The house is surrounded by a garden. Church of al-Mar'ashali Street Address Zamalek 1970s Notes An intelligent design in a rationalized vernacular mode, this church occupies an important intersection in the fashionable Zamalek district of Cairo. Its architect, Ramses Wissa Wassef, is a contemporary of Hassan Fathy, and, like him, he sought architectural inspiration in the vernacular traditions of Egypt. He went on to implement his architectural and socio-religious vision in the arts and crafts center he founded and built in the village of Harraniyya outside Cairo. Source: Rabbat, Nasser O. Harraniya Craft Village Variant Names Harraniya Weaving Village Street Address Harraniya Location Giza, Egypt Architect/Planner Hassan Fathi Architect/Planner Wessa Date 1940 Decade 1940 Building Types educational, urban settlement Notes "The Harraniya Crafts Centre is a third community project, which like those of Lulu'at al-Sahara and Garagos, is much less well known than New Gourna, yet represents an important member of the group of examples of this typology designed by Fathy. Carried out in collaboration with the architect Rarnses Wissa Wassef, and the Ministry of Scientific Research, the centre was based on a dual belief in the natural creative ability of children and the need for the material self-sufficiency to allow that natural creativity to have free rein. As the son-in-law of the famous educator Habib Gorgy, who first promoted these ideas in Egypt, Ramses Wissa Wassef became intrigued with the concept of a utopian, self-contained weaving village in which Gorgy's theories could be tested. Along with Fathy and Hamid Said, Wassef also believed in the critical importance of reviving national, traditional crafts in the face of the threat of expanding industrialization. The essence of the village, which radiates out from a man-made lake at its apex, is the reciprocal relationship between the housing units and the fields next to them. These fields, which were intended to sustain both the sheep from which the wool for the weaving would be taken, and the plants that would yield the natural dyes to colour them, symbolically alternate with the houses in which the young weavers live. In this way a repeating rhythm of protected agricultural areas and contained pedestrian streets is set up by the interlocking lines of the houses between them. The direct contact between the houses and the fields also allows the farm animals to be brought into the interior of each house, which is an important factor in rural Egypt, and was first attempted by Fathy in his design of the houses in New Gourna. As the plan progresses from the green agricultural perimeter towards the lake at its apex, it becomes more and more public in function, and this is where the majority of the facilities for weaving, selling, storage and shipping are located. Although never realized in the form documented here, the Ramses Wissa Wassef weaving village was finally built in Shabramant near Harraniya, and was the recipient of an Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1983. The extraordinary tapestries woven by the children there have become the pride of Egyptian contemporary art, and are now exhibited in galleries throughout the world." (Source: Steele, James. 1989. The Hassan Fathy Collection. A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern, Switzerland: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture. 22) Mohi Houssin Residence Giza, Egypt 1970 Notes The Mohi Houssen Residence is a traditional house with a workshop for an Egyptian sculpture situated in a private garden. The architect, through his design, sought to provide the artist and his family with a comfortable house and a functional workshop at a minimal cost. The residence is designed as two separate sectors; the larger sector comprises the residential area, which covers both the north and east side of the courtyard. The other sector comprises a ceramic workshop that encloses the courtyard on the west. The house is entered by a porch at the northeast corner which leads to an entry court facing the internal courtyard. The accommodation is divided into two parts: the north end is for the family, with three bedrooms and a bathroom on two levels. A corridor leads to the other half of the house where there is a domed sitting room, dining area kitchen and workshop. The domes and vaults are constructed using red bricks, while ceilings were built of mud-brick. The walls are load-bearing roughhewn limestone. (Source: AKTC) Ramses Wissa Wassef Arts Center Street Address just outside the ancient village of Harraniya Giza, Egypt 1974 Decade 1970s public/cultural Notes Near the pyramids at Giza, the centre was founded in the early 1950s by the late architect Ramses Wissa Wassef as a weaving school. It has since evolved to comprise workshops and showrooms, a pottery and sculpture museum, houses and farm buildings, constructed entirely of mud brick. For Wissa Wassef, vaulted and domed mud brick structures represented something quintessentially Egyptian as these forms had been adopted in turn by Paranoiac, Coptic and Islamic civilisations. The choice of this traditional technology also reflected his desire to transmit the values of handicraft to succeeding generations in a rapidly industrialising country. The jury commended the centre for "the beauty of its execution, the high value of its objectives, the social impact of its activities as well as the power of its influence as an example." Recipient of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 1983. (Source: AKTC)