Talking with Horses

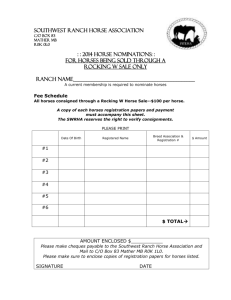

advertisement