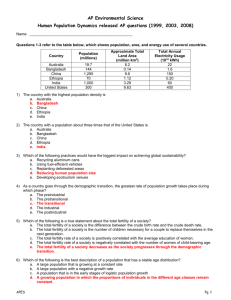

Ch 3 hans-Peter fertility-new

advertisement