Time Course of Vomiting

advertisement

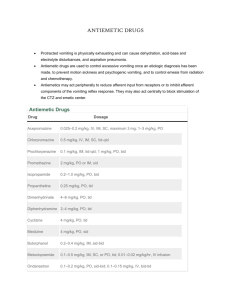

DRUGS OF TODAY Vol. 21, No. 4, 1985, pp. 177-185 MECHANISMS AND TREATMENT OF CYTOTOXIC-INDUCED NAUSEA AND VOMITING A.L. Harris Cancer Research Unit, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4LP, UK Introduction The most important subjective side-effects of cancer chemotherapy are nausea and vomiting. It is not known how such a wide variety of cytotoxic agents with different structures, modes of action and lipid solubility produce nausea and vomiting. Neurological Pathways, Transmitters and Receptors Involved in Nausea and Vomiting Chemotherapy-induced vomiting is thought to act via the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) in the area postrema in the floor of the 4th ventricle (1). However, there are species differences, and in the cat upper abdominal de-deafferentation is necessary to abolish mustine-induced vomiting (2). Afferent pathways to the vomiting centre pass via the tractus solitarius and its nucleus, and efferent pathways exit via the nucleus ambiguus and the dorsal motor nuclei of the vagus. Receptors for various different neurotransmitters are present in these pathways, e.g. muscarinic cholinergic receptors for the tractus solitarius and the nucleus ambiguus, and histamine H1-receptors for the nucleus of the tractus solitarius and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; opioid receptors are also present in these two nuclei and dopamine D2-receptors are present in the CTZ (3). Over 17 putative neurotransmitters have been described in or near the nucleus of the tractus solitarius and the area postrema, so that specific linking of any neurotransmitter to chemotherapyinduced nausea and vomiting at the CTZ is not possible (4). However, it is possible to conclude from the anti-emetic effects of various drugs which neurotransmitters may be important in mediating nausea and vomiting at some sites in the overall reflex pathways. Emetic Potential of Different Cytotoxic Drugs Although all anticancer cytotoxic drugs can produce nausea and vomiting, there are marked differences in the emetic effect between different drugs that have otherwise similar marrow toxicity or therapeutic effect. Drugs can be ranked according to their emetic potential using average clinical doses (Table I). It is clear that drugs such as antimetabolites and Vinca alkaloids that primarily interfere with de novo DNA synthesis or mitosis are much less emetic than drugs that primarily inhibit RNA and protein synthesis. Time Course of Vomiting The drugs that induce emesis in most patients are also the ones with most rapid onset of nausea and vomiting. The onset of vomiting is delayed from 1-12 hours after an intravenous dose. It is not known why there is such a delay in onset, since peak levels of drug are present in plasma within minutes of the intravenous bolus and the CTZ is outside the blood-brain barrier. The delay suggests that some secondary mechanisms need to be activated to produce stimulation of the CTZ. For cyclophosphamide, the time course of nausea and vomiting may be related to the need to convert it to active metabolites (5), but peak levels of active metabolites are present within 2 hours of dosing (6) and this alone cannot explain the delayed onset. 178 Secondary Mechanisms for Cytotoxic DrugInduced Vomiting The emetic ranking by biochemical site of action of the cytotoxic drugs and the delayed onset could be accounted for if cytotoxic drug-induced vomiting depends on the activities of rapidly turning-over enzyme systems (with an intracellular half-life of approximately 6 hours) that are responsible for the breakdown of a neurotransmitter (7). In the absence of such enzymes, the neurotransmitter would increase in concentration and stimulate receptors in the CTZ. Since different agents inhibit enzymes at different points in their synthetic pathway, and thus at different speeds, the involvement of enzyme systems would explain the observed differences in cytotoxic drug-induced vomiting (Table I). Anti-Emetic Centre Costello and Borison showed that opiates have anti-emetic as well as emetic effects (8). They suggested that there may be an anti-emetic centre, possibly in the medullary reticular formation, producing an endogenous anti-emetic zone via enkephalins, Cytotoxic drugs crossing the blood-brain barrier at the area.postrema may gain access to the antiemetic centre, since it has been shown that systemically administered peroxidase quickly inun-dates brain parenchyma adjacent to the area out-side the blood-brain barrier (9). Inhibition of enzymes MEDICAMENTOS DE ACTUALIDAD making enkephalin in this area may contribute to the emetic effects of cytotoxic drugs. Anti-Emetic Effects of Steroids and Benzodiazepines If the anti-emetic centre is important, then steroids may help by effects on the blood-brain barrier and decreasing drug access to the anti-emetic centre. Prostaglandins are emetic and steroids could reduce their release by glia cells in the vicinity of the area postrema which could be secondary to cytotoxic drug effects. Steroids also interact with enkephalin release (10). Benzodiazepines bind to GABA receptors but their anti-emetic effect is more likely to be mediated by the limbic system rather than directly on the CTZ (11). Anticipatory Nausea and Vomiting Whatever the biochemical mechanisms initiating nausea and vomiting, pretreatment nausea and vomiting can develop. This usually occurs after several courses of chemotherapy, and may gradually become worse with time and persist after stopping chemotherapy when patients attend for followup. This probably represents a conditioned reflex and shows that higher cerebral or limbic stimuli may be very important in chemotherapy-induced vomiting. About 1-10% of patients develop this problem and 1-5% of patients may refuse chemotherapy because of anticipatory nausea and vomiting. DRUGS OF TODAY Vol. 21, No. 4, 1985 Treatment of Nausea and Vomiting It is Important to give anti-emetics before chemotherapy and to ensure that adequate doses have been given to cover the peak onset time of vomiting. Anti-emetics may also need to be continued for 24 hours or longer, depending on the cytotoxic drug. Thus, in one placebo-controlled study of high-dose metoclopramide given before and 30 minutes after chemotherapy, no anti-emetic effect was noted because nausea and vomiting did not start until 6-12 hours after chemotherapy and lasted for 24-48 hours (13). Apparently minor considerations can be important. Administration of chemotherapy to patients who are sitting is less emetic than giving therapy when they are lying flat. Effervescent drinks can reduce nausea and are better tolerated than flat drinks. These observations suggest that other stimuli from the gastrointestinal tract or vestibular apparatus may be synergistic with chemotherapy in producing vomiting and nausea. Patients with a previous history of motion sickness are more likely to have severe nausea and vomiting (14). Several different types of drugs have been used to treat nausea and vomiting. There are many problems in interpreting some of the trials because patients treated with different drugs, with conditioned vomiting or with different tumours have been included in the same study. Very few trials have tried to optimise drug dosage in individual patients. Therefore, the doses used in different trials can vary 5-fold, even when "high-dose" anti-emetics are not being evaluated. However, many randomised trials have been published and are useful in assessing the relative efficacy of the anti-emetics. Dopamine Antagonists Phenothiazines Prochlorperazine [I] is one of the most widely used anti-emetics and has become the standard to which newer anti-emetics are compared. In randomised trials it has been shown to be more effective than placebo (14-17), but most of the newer anti-emetics have proven superior in randomised trials. Metoclopramide (18-22), nabilone, tetrahydrocannabinol, levonantradol (23-29), droperidol and dexamethasone were all more effective than prochlorperazine or chlorpromazine. In some trials doses as low as 15 mg/day prochlorperazine were used, and in others 75 mg/day. There is a need to optimise present drug use based on a knowledge of pharmacokinetics and relationships of anti-emetic drug levels to therapeutic ef- 179 fect. Recently, higher doses of prochlorperazine — 30 mg every 3 hours intravenously— were found to be effective in controlling cisplatin-induced emesis (30,31). Butyrophenones Droperidol [II] was more effective than prochlorperazine or chlorpromazine plus promethazine (33), and haloperidol [III] has been shown to be antiemetic (34). Both these butyrophenones produce drowsiness at anti-emetic doses. The optimum dosage is not yet defined, with 1-10 mg droperidol being used intravenously in different studies (35, 36). Metoclopramide Metoclopramide [IV] is a procainamide derivative with peripheral and central dopamine antagonist activity. Conventional doses of metoclopramide have been compared with prochlorperazine. Although metoclopramide was more effective than prochlorperazine, neither drug was particularly effective in controlling cisplatin-induced emesis (20, 3740), The work of Graiia et al. (20, 39) showed that higher doses of metoclopramide (2 mg/kg 4 times a day) were more effective than placebo, prochlorperazine or cannabinoids. The higher doses of metoclopramide were associated with diarrhoea, drowsiness and extrapyramidal side-effects. The latter were more common in young patients and were readily controlled with diazepam or anticholinergic antiparkinsonian drugs. Oral high-dose metoclopramide 2 mg/kg produces plasma levels equivalent to 2 mg/kg i.v. (41, 42). In randomised trials it was as effective as intravenous metoclopramide (40, 43, 78). Intermediate-dose i.v. metoclopramide 1 mg/kg was equivalent in activity to 2 mg/kg i.v. (45). One pharmacokinetic evaluation suggested that plasma levels > 850 mg/ml were necessary for optimal control (46). The above studies show the need for futher evaluation of pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy. Domperidone Domperidone [V] is a benzimidazole derivative and peripheral dopamine receptor blocker. It does not cross the blood-brain barrier and hence would be expected to have fewer extrapyramidal side-effects. The latter have only rarely been reported. Domperidone was found to be superior to placebo (47-49). Domperidone has been compared with metoclopramide in adults and in children, who would be more susceptible to extrapyramidal side-effects. 180 In adults domperidone was equivalent (47) or superior to metoclopramide (51), and in children domperidone was superior (50). Although higher doses of domperidone could be given because of the lack of central nervous system side-effects, studies with higher doses have been curtailed because of possible cardiac arrhythmias and convulsions (52). Cannabinoids Three cannabinoids have undergone extensive clinical trial —A-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [VI], nabilone [VII] and levonantradol [VIII]. AH are more effective than placebo (24, 28, 53-55) and have been shown to be more effective than prochlorperazine. They do have side-effects which make them less acceptable to older patients such as dysphoria, dry mouth and somnolence. They have been useful in treating cisplatin-induced emesis in younger patients. Taking the long plasma half-life of THC into account, Meyers et al. (56) used 5.0 mg/m2 THC 4-hourly rather than 10 mg/m2, with significantly fewer side-effects and maintained antiemetic effect. Benzodiazepines Lorazepam [IX] has been assessed as an antiemetic. In one trial the effect on memory of vomiting was more marked than the anti-emetic effect, and patients preferred lorazepam (57). Lorazepam has been compared with high-dose metoclopramide and was equally effective (40). Sedation is produced at anti-emetic doses. Steroids Dexamethasone [X] is the most widely used steroid in anti-emetic trials. It is superior to placebo and prochlorperazine (58, 60-62). It is equal to intermediate-dose metoclopramide (1 mg/kg x 4) (59) in controlling cisplatin-induced emesis. There is also a feeling of well-being and mood improvement when steroids are used as anti-emetics. Dexamethasone is currently being evaluated in many combination studies. Dexamethasone added to highdose metoclopramide was significantly better than high-dose metoclopramide alone (63), and several uncontrolled studies have reported this combination to produce effective control of cisplatin-induced vomiting (64, 65). Dexamethasone plus lorazepam' was also more effective than high-dose metoclopramide (66). MEDICAMENTOS DE ACTUALIDAO Other Drugs - Nortriptyline, Scopolamine, Opioids Nortriptyline [XI] in combination with fluphenazine [XII] was superior to fluphenazine or placebo (38). There are few studies of antidepressants as antiemetics, but antidepressants affect a wide range of neurotransmitters are should be furthsr evaluated. Transdermal scopolamine [XIII] was effective in children and this mode of administration is very convenient (67). It would be worth investigating this delivery modality for any currently used anti-emetic. Butorphanol [XIV] has been studied in the ferret and had anti-emetic effects against cisplatin, cyclophosphamide and adriamycin (68). Opioids have not yet been assessed in man. Combination Anti-Emetics Several earlier trials with phenothiazines also used combinations, either with nortriptyline, lorazepam or prednisolone. Most were uncontrolled and therefore the value of combination treatment cannot be determined. Now that several moderately effective anti-emetic drugs are available and have been compared with each other and placebo, properly controlled trials can be devised. Peroutka and Snyder (3) discussed the neurotransmitters involved in vomiting pathways and postulated that combined blockade of histamine Hr, dopamine D2- and muscarinic cholinergic receptors would offer optimum protection against emesis. Results of trials with 3-5 drugs have shown good activity and these studies now need to be randomised versus single agents. Combinations tested include dexamethasome, diphenhydramine and droperidol with (69) or without metoclopramide (70), and a 5-drug regimen of dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, diazepam, metoclopramide and either thienylperazine (71) or prochlorperazine (72). Treatment of Anticipatory Nausea Several behavioural techniques are being evaluated. These include relaxation training, densensitisation and biofeedback (73). However, all these techniques require extra staff and are timeconsuming for patients who may be trying to lead a normal life between treatments. The best way to prevent the problem is adequate control of nausea and vomiting from the first course of chemotherapy onwards. Also, if a finite number of courses of treatment are planned, then the patient can see the end of chemotherapy. In curable tumours such as Hodgkin's disease, teratoma and acute myeloid leukaemia maintenance chemotherapy has been shown in randomised trials to be unnecessary. In DRUGS OF TODAY Vol. 21, No. 4, 1985 181 182 common solid tumours such as oat cell lung cancer 3 months' chemotherapy produces similar results to 2 years' treatment, and in breast cancer 6 months' treatment produces the same results as treatment to relapse. Thus, appropriate planning of treatment and discussion should help to prevent the problem. MEDICAMENTOS DE ACTUALIDAD 6. Conclusions The choice of anti-emetics is wide and will depend on whether the patient is an inpatient or outpatient and how emetic the cytotoxic drugs are. The majority of chemotherapy is given to outpatients and drugs such as dexamethasone, domperidone. and metoclopramide orally are appropriate. Dosages of the dopamine antagonists should be adjusted individually to obtain optimum control. Most inpatients will be receiving more emetic drugs such as cisplatin, ifosfamide and DTIC. Here, intravenous high-dose metoclopramide, intravenous domperidone and intravenous steroids would be used. Also, the more sedative anti-emetics such as lorazepam, droperidol, cannabinoids and chlorpromazine can be added safely. New analogues of many of the more emetic drugs are being evaluated and should greatly reduce the problem of chemotherapy-induced vomiting (e.g. JM-8, JM-9 analogues of cisplatin, oral adriamycin analogues), and further understanding of the neuropharmacology of cytotoxie-induced vomiting may allow more rational development of anti-emetic drugs. References 1. Borison, H.L. and Wang, S.C. Physiology and pharmacology of vomiting. Pharmacol Rev 1953; 5: 192-230. 2. Borison, H.L., Brand, D. and Orchard, R.H. Emetic action of nitrogen mustard in dogs and cats. Am J Physiol 1958; 192: 410-416. 3. Peroutka, S.J. and Snyder, S.H. Antiemetics: Neurotransmitter receptor binding predicts therapeutic actions. Lancet 1982; 1: 658-659. 4. Borison, H.L. and McCarthy, L.E. Neuropharmacologic mechanisms of emesis. In; Antiemetics and Cancer Chemotherapy. J. Laszlo (Ed.). Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore/London 1983; 6-29. 5. Fetting, J.H., Grochow, L.B., Folstein, M.F., Ettinger, D.S. and Colvin, M. The course of 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. nausea and vomiting after high dose cyclophosphamide. Cancer Treat Rep 1982; 66: 1487-1493. Jardine, I., Ferselav, C., Appler, M. et al. Quantitation by gas chromatography chemical ionisation, mass specimmetry of cyclophosphamide, phosphoramide mustard and nornitrogen mustard in the plasma and urine of patients receiving cyclophosphamide therapy; Cancer Res 1978; 38: 408. Harris, A.L. Cytotoxic-therapy-induced vomiting is mediated via enkephalin pathways. Lancet 1982; 1: 714-716. Costello, D.J. and Borison, H.L. Naloxone antagonises narcotic self-blockade of emesis in the cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1977; 203: 222-230. Broadwell, R.D. and Brightman, M.W. Entry of peroxidase into neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system from extracerebral and cerebral blood, J Comp Neur 1976; 166; 257-284. Herz, A., Hollt, V., Gramsch, C. and Seizinger, B.R. In: Regulatory Peptides from Molecular Biology to Function. E. Costa and M. Trabbuch (Eds.). Raven Press 1982; 51-59. Guidotti, A., Baraldi, M. and Costa, E. 1-4-Benzodiazepines and gammaaminobutyric acid: Pharmacological and biochemical correlates. Pharmaco! 1979; 19; 267-277. Penta, J., Poster, D. and Bruno, S. The pharmacological treatment of nausea and vomiting caused by cancer chemotherapy - A review. In: Antiemetics and Cancer Chemotherapy 1983; 81-82. Bul, N.B., Marit, G. and Hoerni, B. High dose metoclopramide in cancer chemotherapyinduced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Treat Rep 1982; 66: 2107-2108. Frytak, S., Moerte.l, C.G. and O'Fallon, J.R. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic for patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med 1979; 91: 825-830. Moertel, C.G., Reitemeier, R.J. and Gage, R.G. A controlled clinical evaluation of antiemetic drugs. JAMA 1963; 186: 116-118. Moertel, C.G. and Reitemeier, R.J. Controlled studies of metopimazine for the treatment of nausea and vomiting. J Clin Pharmacol 1973; 13: 282-287. Orr, L.E., McKernan, J.F. and Bloome, B. Antiemetic effect of tetrahydrocannabinol com- DRUGS OF TODAY Vol. 21, No. 4, 1985 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. pared with placebo and prochlorperazine in chemotherapy-associated nausea and emesis. Arch Intern Med 1980; 140: 1431-1433. Arnold, D.J., Ribiero, V. and Bulkin, W. Metoclopramide vs. prochlorperazine in the prevention of vomiting from diammine dichloroplatinum. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1980; 21: 344. Carr, B., Pulone, B., Bertrand, M., Browning, S., Doroshow, J., Klein, L., Presant, C. and Change, F.F. A double-blind comparison of metoclopramide and prochlorperazine for cisplatinum-induced emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1982; 1: 66. Gralla, R.J., Hri, L.M., Pisko, S.E., Squillante, A.E., Kelsen, D.P., Braun, D.W., Jr., Bordin, L.A., Vraun, T.J. and Young, C.W. Antiemetic efficacy of high-dose metoclopramide. Randomized trials with placebo and prochlorperazine in patients with chemotherapyinduced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med 1981; 305: 905-909. Belt, R.J., Rhodes, J, and Taylor, S. Antiemetic therapy for patients receiving cisdiamminedichloroplatinum(ll): A randomised double-blind study comparing metoclopramide and prochlorperazide. In: Treatment of Cancer Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting. D.S. Poster, J.S. Penta and S. Bruno (Eds.). Masson Publishing: New York 1981; 153-158. Frytak, S. and Moertel, C.G. Management of nausea and vomiting in the cancer patient. JAMA 1981; 245: 393-396. Herman, T.S., Einhorn, L.H., Jones, S.E., Hagy, C., Chester, A.B., Dean, J.C., Furnas, B., Williams, S.D., Leigh, S.A., Dorr, R.T. and Moon, T.E. Superiority of nabilone over prochlorperazine as an antiemetic in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 1979; 300: 1295-1297. Nagy, C.M., Furnas, B.E., Einhorn, L.H. and Bond, W.H. Nabilone antiemetic crossover study in cancer chemotherapy patients. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1978; 19: 30. Steele, N., Gralla, R.J. and Braun, D.W. Double-blind comparison of the antiemetic effects of nabilone and prochlorperazine on chemotherapy-induced emesis. Cancer Treat Rep 1980; 64: 219-224. McCabe, M., Smith, E.P., Goldberg, D., MacDonald, J., Woolley, P.V., Warren, R., Brodeur, R. and Schein, P.S. Comparative trial 183 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. of oral 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and prochlorperazine for cancer chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting. Proc Assoc Cancer Res 1981; 22: 416. Levitt, M., Wilson, A., Burman, D., Fairman, C., Kernel, S., Krepart, G., Schipper, H., Weinerman, B. and Weinerman, R. Dose vs. response of tetrahydrocannabinol vs. prochlorperazine as chemotherapy antiemetics. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1981; 22: 422. Sallan, S.E., Cronin, C., Zelan, M. and Zinberg, N.E. Antiemetics in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer. A randomised comparison of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and prochlorperazine. N Engl J Med 1980; 302: 135-138. Long, A., Mioduszewski, J. and Natale, R. A randomised double-blind crossover comparison of the antiemetic activity of levonantrodol and prochlorperazine. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1982; 1: 57. Carr, B.I., Leong, L., Cecchi, G., Braly, P., Staples, R., Blayney, D., Goldberg, D., Maryslin, K., Bertrand, M. and Doroshow, J. Safety and efficacy of higher than conventional doses of prochlorperazine for chemotherapy-associated emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: G394. Roche, H., Hyman, G,, Nahas, G., Stoopler, M. and Ellison, R.R. Unexpected efficacy of prochlorperazine i.v. in preventing cisplatin induced emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-420. Jacobs, A.J., Deppe, G. and Cohen, C.J. A comparison of the antiemetic effects of droperidol and prochlorperazine in chemotherapy with cis-platinum. Gyn Oncol 1980; 10: 55-57. Roberts, W.S., Wisniewski, B J., Cavanaugh, D. and Marsden, D.E. Intravenous droperidol versus chlorpromazine-promethazine suppositories for the control of cls-platlnum induced nausea and vomiting. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-419. Neidhart, J.A., Gagen, M., Young, D. and Wilson, H.E. Specific antiemetics for specific cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer 1981; 47: 1439-1443. Kelley, S.L., Braun, T.J., Rempel, P., Meyer, T.J. and Pearlman, N.W. Phase 1 trial of droperidol as an antiemetic in cisplatin-induced emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-382. 184 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. MEDICAMENTOS DE ACTUALIDAD Citron, M.L., Johnston-Early, A., Boyer, M.W., Krasnow, S.H., Priebat, D.A. and Cohen, M.H. Droperidol: Optimal dose and time of initiation. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-415. Williams, C.J., Bolton, A., de Pemberton, R. and Whitehouse, J.M. Antiemetics for patients treated with antitumor chemotherapy. Cancer Clin Trials 1980; 3: 363-367. Morran, C., Smith, D.C., Anderson, D.A. and McArdle, C.S. Incidence of nausea and vomiting with cytotoxic chemotherapy. A prospective randomised trial of antiemetics. Brit Med J 1979; 1: 1223-1224. Gralla, R J., Tyson, L.B., Clark, P.A., Bordin, LA., Kelsen, D.P. and Kalman, L.B. Antiemetic trials with high dose metoclopramide: Superiority over THC and preservation of efficacy in subsequent chemotherapy courses. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1982; 1: 58. Bowcock, S.J., Stockdale, A.D., Bolton, J.A.R., Kang, A.A. and Retsas, S. Antiemetic prophylaxis with high dose metoclopramide or lorazepam in vomiting induced by chemotherapy. Brit Med J 1984; 288: 1879. Tyson, L.B., Gralla, R.J., Clark, R.A., Kris, M.G., Bosl, G.J., Reich, L.M. and Young, C.W. High dose oral metoclopramide: Dosefinding efficacy and preliminary pharmacokinetic evaluation. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-397. Alayi, J.6., Torn, S. and Glick, J.H. High dose oral metoclopramide: An effective antiemetic agent. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-424. Anthony, L.B., Krozely, M.G., Woodward, N.J., Hainsworth, J.D., Harde, K.R., Brenner, D.E., Greco, FA., Burish, T.G. Antiemetic effect of oral vs. intravenous metoclopramide in patients receiving cisplatin: A randomised double-blind study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-404. Edge, S., Funkhouser, W., Berman, A., Seipp, C., Tanner, A., Wesley, R., Rosenburg, S. and Chang, A. Randomised evaluation of high dose oral and intravenous metoclopramide in adriamycin/cytoxan induced emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-378. Deppe, G., Smith, P., Wall, D. and Malviya, V.K. A comparison of the antiemetic effects of low dose and high dose metoclopramide in gynecologic cancer patients receiving 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. cisplatin. Proc Am Soc Clin Onco! 1984; 3: C-365. Meyer, R.R., Lewin, M., Drayer, D.E., Pasmartier, M./Lonski, L and Reidenberg, M.M. Optimizing metoclopramide control of cisplatininduced emesis. Ann Intern Med 1984; 100: 393-395. D'Souza, D.P., Reyntjens, A. and Thornes, R.D. Domperidone in the prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by antineoplastic agents: A three-fold evaluation. Curr TherRes 1980; 27: 384-390. Huys, J. Cytostatic-associated vomiting effectively inhibited by domperidone. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1978; 1: 215-218. Hamers, J. Cytostatic therapy induced vomiting inhibited by domperidone: A doubleblind cross-over study. Biomed 1978; 29: 242-244. Swann, I.L., Thompson, E.N. and Qureshi, K. Domperidone or metoclopramide in preventing chemotherapeutically induced nausea and vomiting. Brit Med J 1979; 2: 1188. Gersovich, F.G., Nahrnpd, V.E., Pirole, C.J., Morgenfeld, E.L. and Rivarola, E.J. A doubleblind randomised cross-over study comparing domperidone to metoclopramide as an antiemetic prevention in cancer chemotherapy. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-344. Weaving, A., Bezwoda, W.R. and Derman, D.P. Seizures after antiemetic treatment with high dcse domperidone: Report of four cases. Brit Med J 1984; 288: 1728. Chang, S.E., Soiling, D.J., Stillman, B.C., Goldberg, N.H., Seipp, C.A., Barofsky, I., Simon, R.M. and Rosenberg, S.A. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in cancer patients receiving high dose methotrexate. Ann Intern Med 1979; 91: 819-824. Vincent, B.J., McQuiston, D.J., Einhorn, L.H., Nagy, C.M. and Brames, M.J. Reviewofcannabinoids and their antiemetic effectiveness. Drugs 1983;. 25 (Suppl. 1): 52-62. Stambaugh, J.E., McAdams, J. and Vreeland, F. A phase II randomised trial of the antiemetic activity of levonantrodol in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1982; 1: 62. Meyers, F., Stanton, W., Dow, G. and Rocchio, G. Reduced adverse effects with optimal antiemetic dosage schedule of deita-9-tetra- 185 DRUGS Of TODAY Vol. 21, No. 4, 1985 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. 64. hydrocannabinol. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-366. Friedlander, M., Kearsley, J.H. and Tattersall, M.H.N. Oral lorazepam to improve tolerance of cytotoxic therapy. Lancet 1981; 1: 1316-1317. Cassileth, P.A., Lusk, E.J., Torri, S., DiNubile, N. and Gerson, S.L. Antiemetic efficacy of dexamethasone therapy in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Arch Intern Med 1983; 143: 1347-1349. Cognetti, F., Pinnaro, P., Carlini, P., Conti, E.M., Cortese, M. and Pollera, C.F. Randomised open cross-over trial between metoclopramide and dexamethasone for the prevention of cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. EurJ Cancer Clin Oncol 1984; 20: 183-187. D'Olimpio, J.T., Camacho, F.J., Chandra, P., Lesser, M,, Maldonado, M., Wollner, D. and Wiernik, P.H. Antiemetic treatment of patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy with high dose dexamethasone v. placebo. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-371. Ettinger, D.S., Shcid'er, V , Markman, M., Guaskey, S.A. and Mellits, E.D. Antiemetic efficacy of dexamethasone: Randomised double-blind crossover study with prochlorperazine. Proc Am Soc Clin Or col 1984; 3: C-350. Morrow, G.R., Loughner, J.E. and Bennett, J.M. Prevalence of nausea and vomiting and other side effects in patients receiving cytoxan, methotrexate, fluorouracil therapy with and without prednisolone. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-408. Allan, S., Cornbleet, M., Warrington, P., Leonard, R. and Smythe, J. Trial of dexamethasone and high dose metoclopramide vs. placebo and high dose metoclopramide in els-platinum induced emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-345. McDermed, J.E., Waugh, W.J. and Strum, S.B. A preliminary pharmacokinetic evaluation of high dose metoclopramide in patients receiving cisplatinum chemotherapy. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-409. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. 71. 72. 73. Strum, S.B., McDermed, J.E., Streng, B. and McDermott, N. Combination metoclopramide and dexamethasone -An effective antiemetic regimen in outpatients receiving doxorubicin/ cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-411. Gagen, M., Gochnour, D., Young, D., Gaginella, T. and Neidhart, J. Dexamethasone and lorazepam vs. metoclopramide for prevention of chemotherapy-induced vomiting. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-396. Sawicka, J. and Sallan, S. Transdermal therapeutic system scopolamine: Prevention of vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1977; 18: 302. Schurig, J.E., Florczyk, P., Spender, S.M. and Bradner, W.T. Antiemetic effects of butorphanol against cancer chemotherapeutic agent-induced emesis in ferrets. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1982; 1: 889. Sridhar, K.S., Donnelly, E. and Rosenfeld, C. Combination antiemetic regimen including diphenhydramine, droperidol, metoclopramide and dexamethasone in cis-pistln based chemotherapy regimens. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-388. Aapro, M., Menoud, M., Peytremann, R. and Alberto, P. Antiemetic combination dexamethasone, droperidol, diphenhydramine for DTIC or cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-393. Kessler, J.F., Plezia, P.M., Alberts, D.S., Aapro, M.S., Surwitt, E.A., Graham, V. and Chase, J. Five drug antiemetic combination for prevention of chemotherapy related nausea and vomiting. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1984; 3: C-406. Lane, R., McGee, R. and Riukin, S. Antiemetic combinations for control of platinum induced emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1982; 1: 65. Cotanch, P.H. Relaxation techniques as antiemetic therapy. In: Antiemetics and Cancer Chemotherapy. J. Laszlo (Ed.) Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore 1983; 164-175.

![[Physician Letterhead] [Select Today`s Date] . [Name of Health](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006995683_1-fc7d457c4956a00b3a5595efa89b67b0-300x300.png)