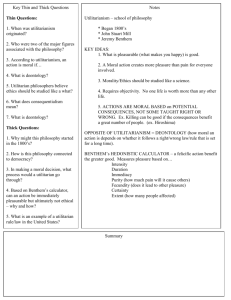

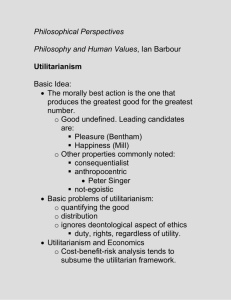

Philosophy: Higher Moral Philosophy

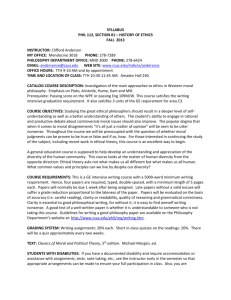

advertisement