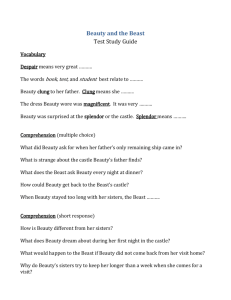

Beauty and the Beast

advertisement

Angela Carter retells the story of Beauty and the Beast in her stories “The Courtship of Mr. Lyon” and “The Tiger’s ride”. Both stories are based upon the traditional fairytale and concern a heroine (Beauty) who finds herself united with a beastly creature in order to help her father and family. Carter, however, offers two distinct stories. “The Courtship of Mr. Lyon” [CML] more closely resembles the traditional tale of Beauty and the Beast, with a heroine who is able to see beyond the ugly appearance of the Beast and is rewarded with his conversion into a handsome prince. “The Tiger’s Bride” [TB] is less traditional and finds Beauty rejecting her father and choosing the Beast but rather than be rewarded with a handsome prince Beauty herself is changed into a beast. The similarities between the two stories address issues of the superficiality of appearance and the inhibiting restraints caused by worldly desires. The differences between the two stories question traditional notions of humanity and savagery while building a new myth centered on a powerful heroine. CML teaches a tired notion of humanity and female figures, while TB offers a dynamic heroine unafraid of her beastliness. It is the character of the father in both of these stories that immediately establishes a difference between them. CML begins not far from the traditional tale of Beauty and the Beast. A father struggles to recreate his destroyed fortune and finds himself battling cold, cruel roads in an attempt to return to his children. He encounters a castle and enters inside to find a beautiful palace equipped with food and warmth for his consumption. There is no known host, and the following morning he attempts to leave the palace in order to return to his children. He sees on the castle wall a rose bush, and he recalls his daughter’s request for a rose upon his return. He picks the rose, at which point the castle’s beastly master appears and questions the father’s gratitude for his generous supply of food and shelter. The beast asks for the man’s daughter in exchange for his selfishness. TB begins quite differently. In this story, Beauty’s father loses her to the beast in a card game. She is forced to leave her father and live with the Beast. Both stories portray a father character central to Beauty’s placement into the potentially perilous world of the Beast. The difference between the two fathers is critical to the development of the two tales. CML shows a good, honest, and hardworking father. His honest fortune was “ruined” (41) by others, and he disturbs the beast’s grounds by picking the rose because of a blissful ignorance motivated by wanting to make his daughter happy and bring her a rose. Beauty responds to such a father figure with duty and love and accepts her fate to stay with the Beast. Describing Beauty’s allegiance to her father, the narrator explains: “Do not think she had no will of her own; only, she was possessed by a sense of obligation to an unusual degree and, besides, she would gladly have gone to the ends of the earth for her father, whom she loved dearly” (45-6). Beauty does not lack the will to make her own choices. It is her sense of obligation and duty she falls prey to. CML’s Beauty is a slave to the kindness of her father. She is powerless in front of this kindness and the loyalty it must deserve. TB deviates from such a traditional notion of power and separates Beauty from her father with more vulgar than sweet prose. Beauty depicts a questionable father figure through her “furious cynicism” (52). This beauty’s father is not unfortunate; he is careless. He is a drunk and loses his daughter to the Beast in a card game. “Gambling is a sickness. My father said he loved me yet he staked his daughter on a hand of cards” (54). Here Beauty is aware of her father’s shortcomings. His flaws are not masked by her sense of duty towards her father. She is clear; she is going to live with the Beast because her father is foolish. The distinction between the two father figures is important in the interpretation of the two stories. CML suggests a weaker Beauty. She cannot escape her sense of obligation towards her father and is ultimately betrayed by her own loyalty into the house of the Beast. Additionally, her downtrodden yet well-intentioned father is nearly punished because of her own desire for a rose. His peril would be her fault. Alternatively, TB presents a character who is aware of her father’s weaknesses. The Beast’s house is not something she foolishly (however reluctantly) agrees to enter, but rather her idiotic father’s displaced punishment. Beauty’s ability to see through such appearances is depicted differently in the two stories as well. One issue of departure between the two stories concerns the Beast himself and a competing notion of humanity/freedom. In CML Beauty is saddened at the sight of her dying friend (the Beast) and kisses him. At that moment, the Beast transforms from an animal-like creature to a handsome man. They marry and stay together forever. In contrast to such a union, TB suggests an alternative ending. In TB, Beauty is so moved by a naked Beast that she responds by shedding her own clothes. The Beast then agrees that she can return to her father. Rather than return, however, Beauty decides to stay with the Beast. She runs through the palace hallways, stripping herself of her clothing. She, finally, unites with the Beast, and she herself changes into a creature similar to the Beast. These plot deviations within the two stories are essential to their respective portrayals of humanity. CML depicts a man, trapped inside a beastly body. Only through Beauty’s ability to “pierce appearances and see your soul” (44) is the true nature of the Beat able to come out. This, as before, depicts a weak beauty. She is never really able to see the truth. It is withheld from her either because she hasn’t the clarity to see or because it is a reward that must be attained through a display of loyalty to the Beast (as to her father). Beauty is a hero for her uncompromising vision, faith, and commitment to what is good. The story of TB, however, depicts no man. The Beast is a beast from the beginning, and demands no such elevation of perception above appearances. Instead, Beauty can be happy with the Beast only when she denies her own humanity. As she considered returning to her father, Beauty recalls, “When I looked at the mirror again, my father had disappeared and all I saw was a pale, hollow-eyed girl whom I scarcely recognized” (65). She then chooses to go to the Beast and become like him. This is a powerful Beauty. She is never deceived by his beastliness, only reluctant to accept it. Additionally, her discovery, the climax of the story, is a discovery of self, not of a man. In this story Beauty is a hero for her wise rejection of her father (who would assuredly sell her again) and her embracement of an animal savagery that offered her complete freedom. Such a freedom is the essence of both heroines, and determines them as weak and powerful. There is a moment in CML where Beauty experiences freedom. After she has left the Beast and returned to her father, she sends the Beast white roses similar to the ones he gave her: “…she experienced a sudden sense of perfect freedom, as if she had just escaped from an unknown danger, had been grazed by the possibility of some change but finally, left intact. Yet, with this exhilaration, a desolating emptiness” (48). Beauty feels freedom because she is momentarily free of her obligations to return to the Beast. The flowers will serve in her absence, and she is no longer constrained by another’s will. The story, however, maintains her weakness. Her willfulness is empty, void of meaning. Not until she returns to the Beast can she truly see of her own accord. The palace, for example, is no longer beautiful and ornate but plain and modest. “There was an air of exhaustion, of despair in the house and, worse, a kind of physical disillusion, as if its glamour had been sustained by a cheap conjuring trick and now the conjurer, having failed to pull the crowds, had departed to try his luck elsewhere” (50). She can see that her perceptions of the house and Beast were illusions, but she is unable to dismiss them. The Beast must first be revealed, and it is only because of his generosity that she is granted vision (how many chances does she get?). Beauty in TB, however, experiences a different kind of freedom. After she disrobes in front of the Beast she says, “I felt I was at liberty for the first time in my life” (64). She experiences freedom in her nakedness. What brings her closer to the animals simultaneously distinguishes her from men. Embracing nakedness embraces the savagery of the Beast, and Beauty accepts this. This story, unlike CML, maintains Beauty’s strength. Rather than discover her own disillusionment, Beauty experiences self-discovery. The end finds the birth of a new Beauty. “And each stroke of his tongue ripped off skin after successive skin, all the skins of a life in the world, and left behind a nascent patina of shining hairs” (67). There is no skin left, there is no old world left, there is only fur and a transformed version of what existed before. These two stories are powerful manipulations of a fairy tale that has, for generations offered an image of women, power, and passion. With two distinct retellings, Carter offers audiences and alternative to the traditional myth. The search for a truly liberating myth, however, is also truly a challenge. It is – after all – a myth. While CML attempts to advocate a less superficial humanity, one where beastliness is acceptable and loveable, TB questions humanity. For women and her traditionally powerless roles in fairy tales, these two myths offer her two different possibilities. One (CML) offers her a worth based on her obligation to a sense of morality. The other (TB), one more powerful, offers her a chance to shed her status (sinful or not) of woman and join a new family where naked truth is valued above perception.