16th Breast Cancer Final

advertisement

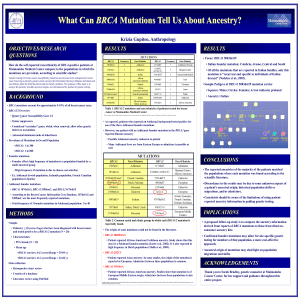

Breast Cancer Susceptibility Genes and Risk Reduction. Olufunmilayo I. Olopade 1 Abstract • Inherited mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes are the strongest indicators of breast and/or ovarian cancer risk. • Understanding the limitations of the various mutation ascertainment methods is critical when assessing of the literature reporting BRCA1/2 mutation frequencies in different populations. • Prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations among high-risk cancer patients may vary by ethnicity, study inclusion criteria, and mutation detection techniques. • Many studies focus on the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations in different ethnic populations. However, the cancer risks associated with these mutations are a function of mutation penetrance. • Founder mutations in some populations may affect the prevalence of inherited BRCA1/2 mutations. The limited genetic variability in members of founder populations can help reduce the variability in penetrance of BRCA1/2 mutations, providing a more reproducible assessment of true BRCA1/2-associated cancer risk in these populations. • Clinicians interested in providing personalized cancer-risk counseling for patients should understand the contributions of BRCA1/2 mutations in diverse populations, BRCA1/2 mutation penetrance, and potential modifying factors particular to patients’ ethnicity, family history, and environmental influences. 2 Introduction Numerous epidemiological factors affect the likelihood of developing breast and ovarian cancer, but no other predictor is as powerful as an inherited mutation in the tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 or BRCA2. Even though hereditary breast cancer accounts for only 5-10% of all breast cancer cases, individuals carrying mutations in one of these genes have a 40-80% chance of developing breast cancer, making these mutations the strongest breast cancer predictors known 1-3. BRCA1 and BRCA2 were molecularly identified in 1994 and 1995, respectively, and since then patients with strong personal and/or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer have been counseled to seek molecular genetic testing for germline mutations in these genes 4,5. In the context of this review, the term ‘mutation’ will be used to refer to a disease and/or risk-associated deleterious genetic lesion. Indicators of inherited breast and/or ovarian cancer syndromes include early age of cancer onset, multiple affected individuals within a family (especially multiple first-degree relatives), the development of bilateral disease and males with breast cancer. It has been estimated that 0.7-29% of such families are accounted for by mutations in BRCA1, and 1.5-25% are accounted for by mutations in BRCA2 6-9. Although these reports represent a very wide range of population proportions, the majority of evidence suggests that, in general, germline mutations in known breast cancer risk genes account for about 20% of breast cancers associated with family history 10,11 (previously reviewed by Szabo and King, 1997 12). It is therefore critical to understand the contribution of BRCA1/2 mutation-associated risks to these breast cancer populations. Studies of BRCA1/2 mutation frequencies have revealed great differences in populations from different geographic regions and ethnicities. For example, 34% of Swedish highrisk families carry deleterious BRCA1 mutations, and 69% of these are a single mutation. However, only 2% carried mutations in BRCA2 13. By contrast, 32% of similarly highrisk Sardinian families carry one of two common BRCA2 mutations, and 11% carry a single BRCA1 mutation 14. In Poland, 64% of high-risk families carry a BRCA1 mutation (one of nine recurring mutations), but rarely any BRCA2 mutations 15 (similar ranges are reviewed by Szabo and King 12). As we approach the goal of personalized medicine, it is important to recognize the role of an individual patient’s genotype to her breast cancer risk, as well as the gene-gene and gene-environment relationships that may modify mutation penetrance in each individual. References 1. 2. Claus, E.B., Risch, N. & Thompson, W.D. Genetic analysis of breast cancer in the cancer and steroid hormone study. American Journal of Human Genetics 48, 23242 (1991). Schubert, E.L. et al. BRCA2 in American families with four or more cases of breast or ovarian cancer: recurrent and novel mutations, variable expression, 3 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. penetrance, and the possibility of families whose cancer is not attributable to BRCA1 or BRCA2 [see comments]. American Journal of Human Genetics 60, 1031-40 (1997). Easton, D.F., Ford, D. & Bishop, D.T. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. American Journal of Human Genetics 56, 265-71 (1995). Wooster, R. et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature 378, 789-92 (1995). Miki, Y. et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 266, 66-71 (1994). Mann, G.J. et al. Analysis of cancer risk and BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence in the kConFab familial breast cancer resource. Breast Cancer Res 8, R12 (2006). McKean-Cowdin, R. et al. BRCA1 variants in a family study of AfricanAmerican and Latina women. Hum Genet 116, 497-506 (2005). Saxena, S. et al. Contribution of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequence alterations to breast cancer in Northern India. BMC Med Genet 7, 75 (2006). Peto, J. et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with early-onset breast cancer [see comments]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 91, 943-9 (1999). Ponder, B.A., Antoniou, A., Dunning, A., Easton, D.F. & Pharoah, P.D. Polygenic inherited predisposition to breast cancer. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 70, 35-41 (2005). Easton, D.F. How many more breast cancer predisposition genes are there? Breast Cancer Res 1, 14-7 (1999). Szabo, C.I. & King, M.C. Population genetics of BRCA1 and BRCA2 [editorial; comment]. American Journal of Human Genetics 60, 1013-20 (1997). Bergman, A. et al. A high frequency of germline BRCA1/2 mutations in western Sweden detected with complementary screening techniques. Fam Cancer 4, 89-96 (2005). Palomba, G. et al. Spectrum and prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Sardinian patients with breast carcinoma through hospital-based screening. Cancer 104, 1172-9 (2005). Gorski, B. et al. A high proportion of founder BRCA1 mutations in Polish breast cancer families. Int J Cancer 110, 683-6 (2004). 4